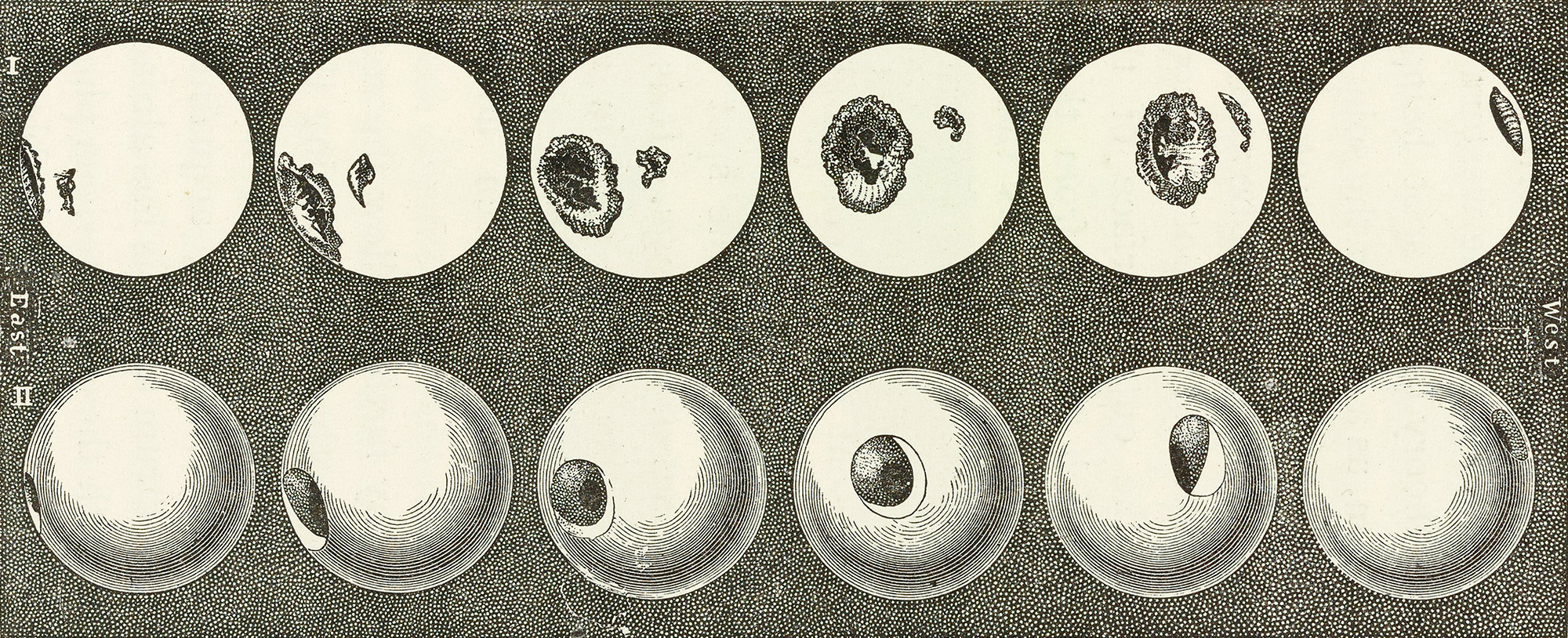

Richard Carrington wasn’t expecting anything dramatic that day. As the scion of a wealthy English brewer, Carrington built his own private astronomical observatory and loved to while away the hours studying the sun. He was especially intrigued by sunspots—irregular patches of darkness on the solar surface. No one knew what sunspots were in his day, but when Carrington sat down to examine them on September 1, 1859, he noticed that there were a lot more than usual.

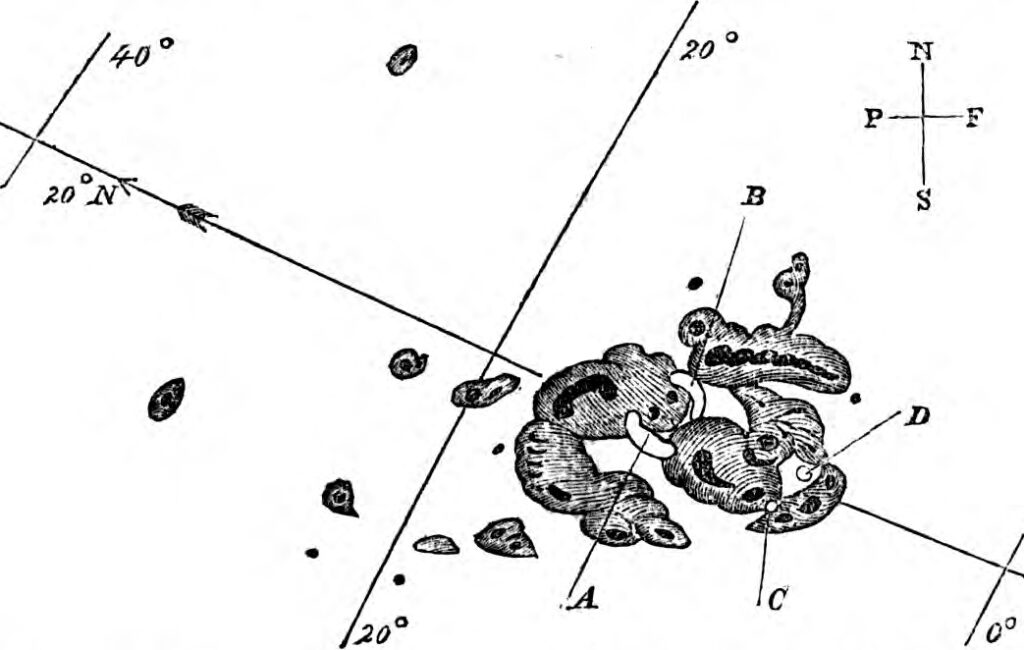

Suddenly, just before noon, he saw something bizarre—an eruption. A giant geyser of plasma leapt right off the surface of the sun. After a moment’s bewilderment, Carrington jotted down notes and made detailed sketches, unsure what to make of what he had witnessed.

We now call these eruptions solar flares, and as far as we know, Carrington was the first person in history to see one. But what made the event truly special—and what frightens scientists about solar flares today—is what happened next.

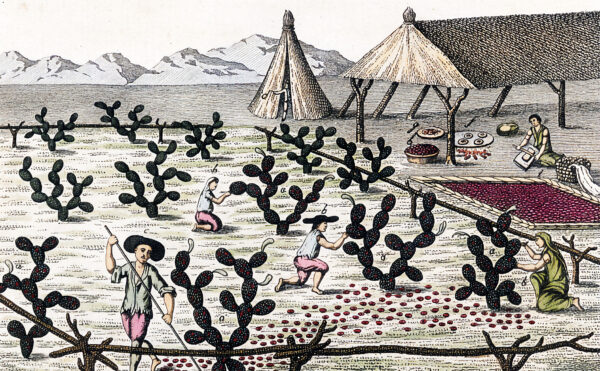

That night, people across the globe reported unusually vivid auroras in the heavens. And not just at high latitudes: the northern lights appeared as far south as Venezuela. In the northeast United States, people could read newspapers outdoors well past midnight. In the Rocky Mountains, the bright sky set birds to chirping, and dozens of grumbling gold miners rolled out of bed and started making breakfast, assuming it was dawn.

Telegraph systems went haywire as well. Operators got electric shocks, and a few telegraph stations started on fire. Most eerie of all, some telegraph machines began spewing gibberish, as if possessed by demons. Operators discovered they could disconnect their machines from their batteries and still send messages. One pair in Boston and Maine held a two-hour conversation with no power source.

It was one the strangest nights anyone could remember. And as these tales trickled in to astronomer Richard Carrington in England, his thoughts returned to the eruption he had seen on the surface of the sun. Could there be a connection?

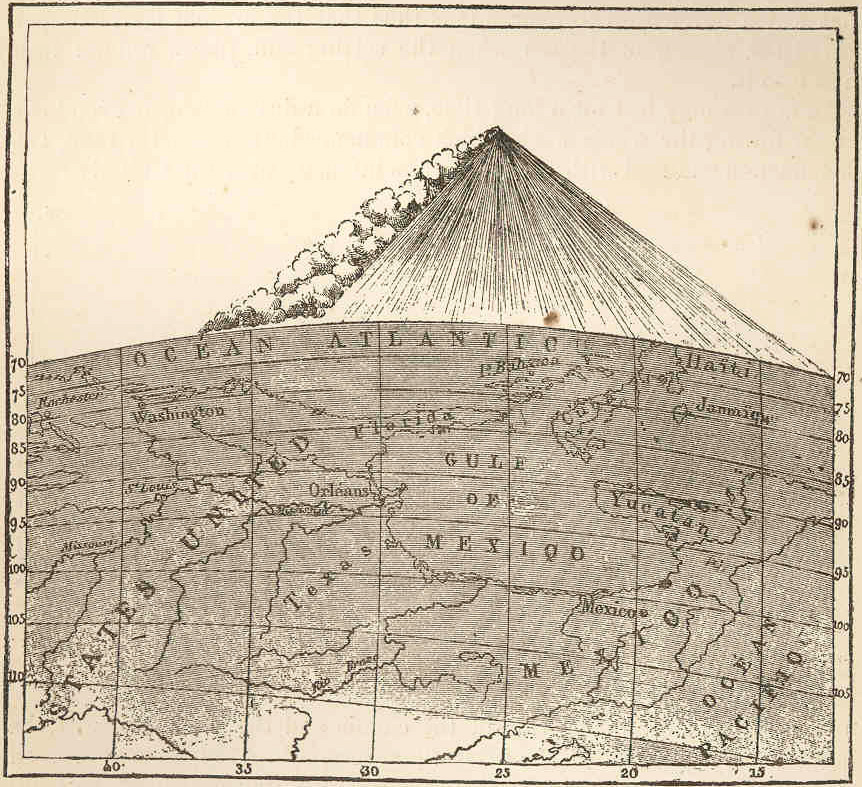

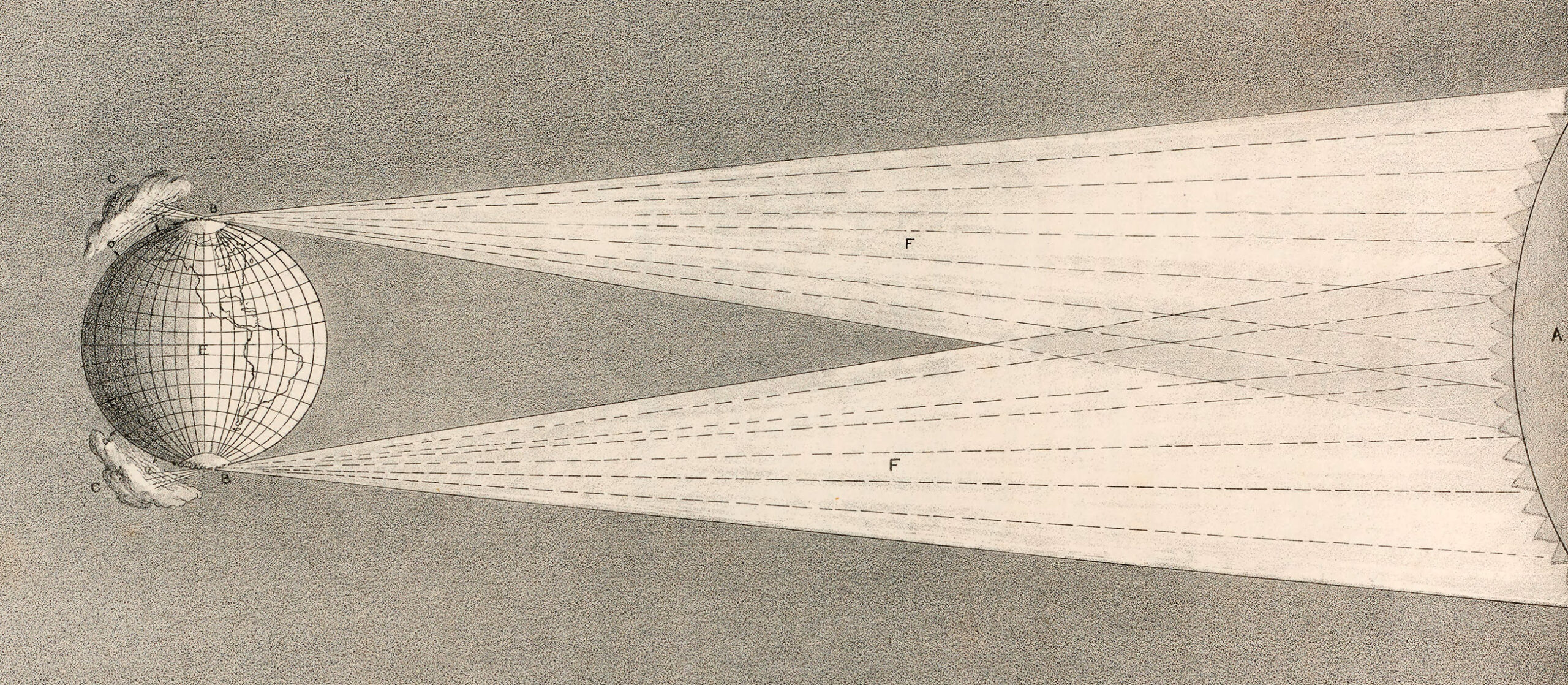

We now know his hunch was right. Solar flares often take place during larger events called solar storms, which involve the ejection of radiation (gamma rays, X-rays) and particles (mostly electrons and protons) from the sun’s surface. A similar storm produced vivid auroras around the world in May 2024, with the northern lights visible as far south as Hawaii.

Scientists don’t know what exactly causes solar storms, but they have linked them to the sun’s magnetic field. The sun consists mostly of plasma, a scorching-hot state of matter where atoms separate, or dissociate, into charged particles. Charged particles in motion create magnetic fields, and the rotation of the sun around its axis therefore produces a strong magnetic field.

But that magnetic field is not stable. In 1863, a few years after seeing the solar flare, Carrington made an important discovery about the sun’s rotation. The sun is a fluid body, not solid, and by tracking the movement of sunspots over time, he determined that different parts of the sun rotate at different speeds. Specifically, the solar equator rotates once every 25 days, while the sluggish poles take 33.

The upshot is that different patches of charged, magnetic field–generating plasma are swirling around at different rates. This causes energy and tension to build up in complicated ways, analogous to a buildup of static electricity. And every so often, all the extra energy erupts at once in bursts of radiation and particles.