Sylvia Earle was surrounded. In every direction, as far as she could see, the deep, translucent blue of the Pacific Ocean pressed against her, the water so vibrant it seemed “to glow with internal light.”

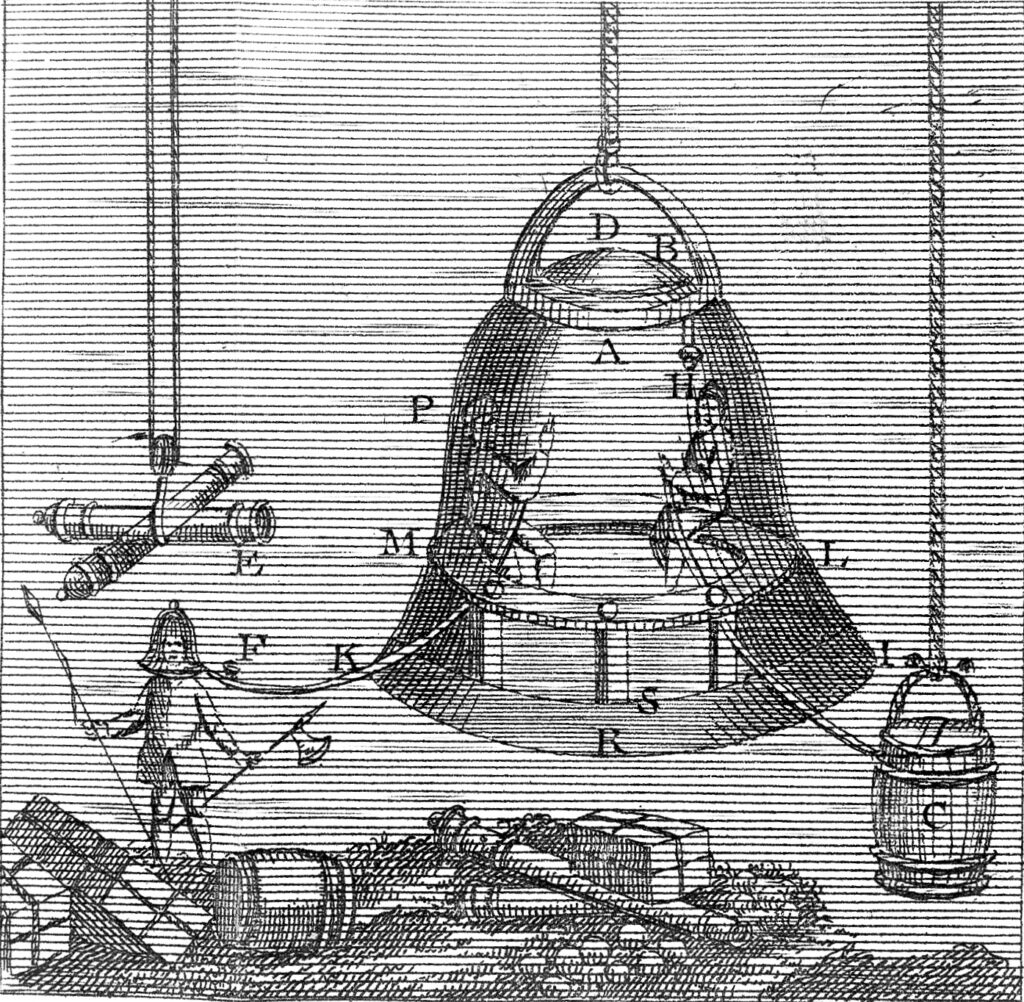

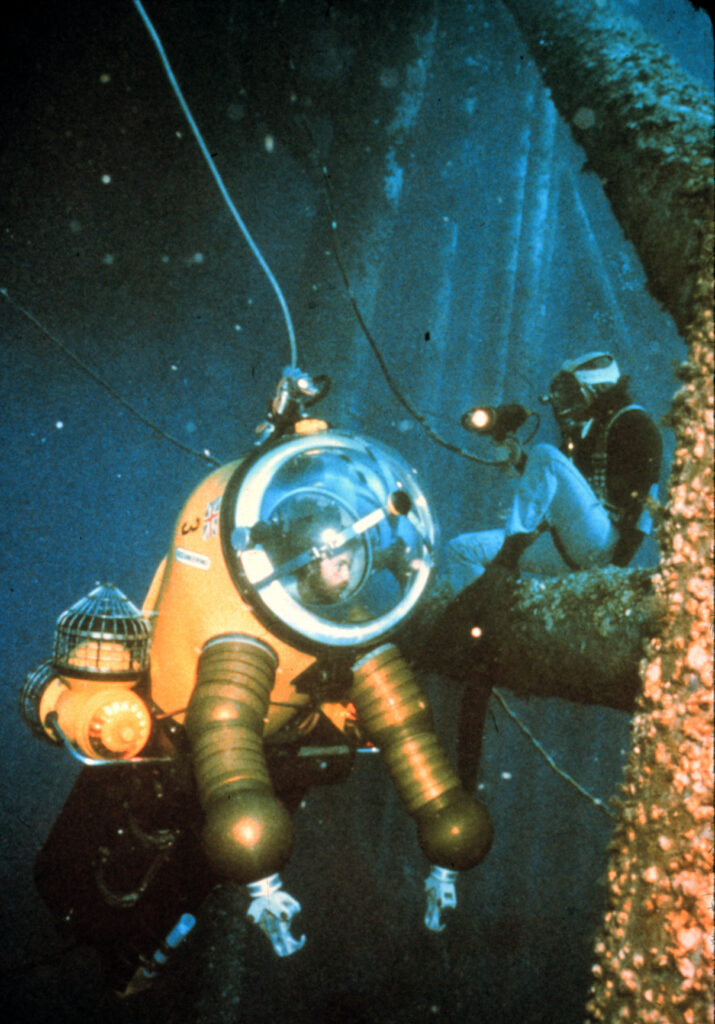

At 1,250 feet below the surface, as far from fresh air as the Empire State Building is tall, she was subject to more than 550 pounds of pressure—the equivalent of a hammerhead shark’s bite landing on every inch of her armored diving suit. It was enough to collapse her lungs instantly, threatening a most sudden death on that September day in 1979, if not for the advanced technology protecting her. With a supply of recirculating air chemically scrubbed of carbon dioxide, she could comfortably breathe even at this staggering depth, making her the envy of a long lineage of divers.

Six miles off the coast of Oahu, Hawaii, Earle unstrapped from the outboard platform of the submersible that had dragged her like captured prey to these lethal depths. But she felt no trepidation. She was eager to “walk among the unusual animals, to look and touch, to explore at will.”

Despite having spent thousands of hours underwater, she had never experienced anything like this. No human had. She was the first to operate any diving equipment this deep without a tether to the surface.

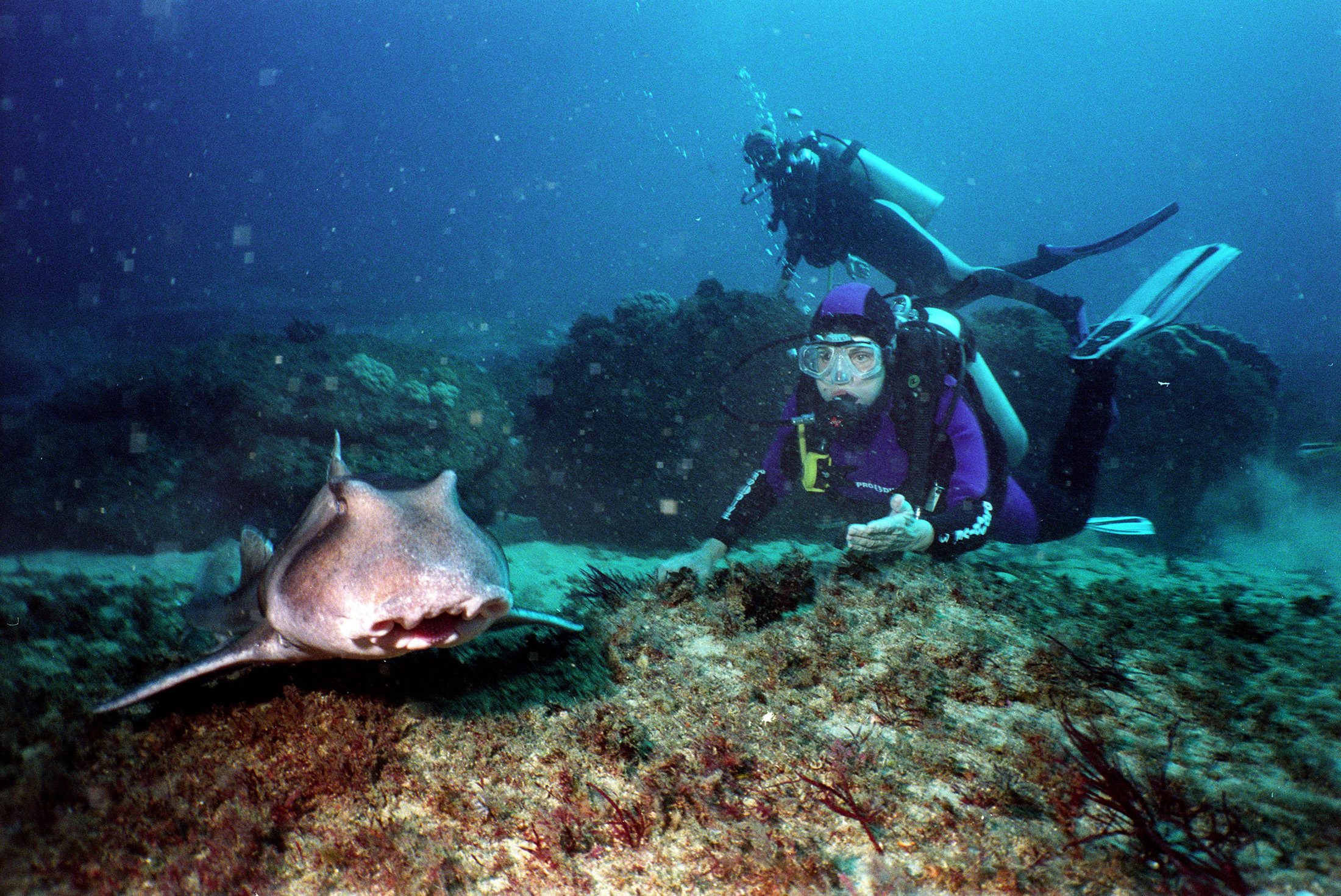

Down here, bioluminescence was closer to a rule than an exception. All around were “sparks of living light, blue-green flashes of small transparent creatures brushing against my faceplate,” she later recalled. Deep-sea rays hovered “like enormous butterflies.” An 18-inch shark with glowing green eyes swam past, followed by a slender, nearly iridescent lanternfish studded with a row of lights down its side. She marveled at a five-foot-tall bamboo coral’s instinctive response to her touch, contemplating the purpose of the rings of blue light that cascaded up and down its length.

“Never before had anyone had a chance to venture solo into that nearly dark, nearly light realm with a mandate simply to explore,” she wrote. “I was given license to let my curiosity take me where it would—to prowl around like a cat in a new house, whiskers twitching, alert to the slightest movement, sensitive to subtle nuances of shape, light, and sound.”