Smith Griswold pushed past the group of newsmen and stepped into the tiny greenhouse. He rolled up his shirtsleeves, sat down, and smiled for the cameramen. Then his employees turned on the ozone machines. Two hours later Griswold emerged from the smog-filled chamber sweating, blinking, and coughing. The ozone had made his Coca-Cola taste strange and disrupted his concentration. He had to think carefully before speaking. “I volunteered for this test to learn firsthand the physiological and psychological effects people may be called upon to endure during smog attacks,” he told the reporters.

At the time of Griswold’s experiment in July 1956, smog was a worsening but still relatively new problem in Los Angeles, though one that threatened to upend the city’s politics. Part of his job as the county’s air-pollution control chief was to convince the public that the county government could deal with the issue. Griswold was candid about the enemy he held responsible for L.A.’s smog attacks: greedy automakers in Detroit. If the automakers would just adopt smog-control devices, L.A. could enjoy its sun and its cars.

Nine years before Griswold’s publicity stunt, Los Angeles County had created a first-of-its-kind Air Pollution Control District (APCD). The first director, a Midwesterner named Louis McCabe, initially focused his efforts on reducing black smoke, soot, and stinky sulfur dioxide, air pollutants that were the bane of the coal-fired Midwest.

But postwar L.A. was changing fast. As the population swelled, highways and subdivisions replaced citrus orchards, industry burgeoned, and smog became L.A.’s most obvious problem. On some days the air made people’s eyes water, irritated their throats, and left them short of breath. As to the causes of smog and what should be done to reduce it, these were politically fraught questions with no widely agreed-on answers. Louis McCabe’s approach pleased no one, and he was replaced by an engineer named Gordon Larson in 1948.

Around that time chemist Arie J. Haagen-Smit had suggested that smog is created when sunlight breaks down incompletely burned gasoline and other hydrocarbons. Following the science Larson shifted the APCD’s focus to automobile exhaust and the region’s ubiquitous low-temperature backyard trash incinerators.

As Southern California’s mountains faded behind increasingly thick, brown haze, some residents believed Larson had lost sight of the real culprits: why blame ordinary people rather than tackling politically powerful industries that produced more visible emissions, such as oil refineries and oil-burning manufacturers? When pollution experts appointed by Governor Goodwin Knight tried to reassure the public that smog posed no health hazard—or at least didn’t cause cancer—suspicions grew that elected officials were more interested in protecting the financial health of their political patrons than the physical health of their constituents.

In 1954 public irritation turned into political action amid a two-week stretch of stinging, acrid air. OnOctober 20, thousands of mostly middle-class, suburban residents attended a public meeting at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium. Francis Packard, the insurance salesman who called the meeting, decried the “scientific mumbo jumbo” and “bureaucratic inertia” that kept the government from solving the smog problem. The crowd watched a documentary that showed scenes of heavy traffic on parkways producing no visible pollution, while huge clouds of smoke billowed from refineries. A popular radio announcer asked, “Has the public been fooled by facts and figures?” “Yes!” the crowd roared back. Did the crowd believe the governor’s health expert who said smog posed no immediate health hazard? “Three thousand voices shouted NO!” reported the Los Angeles Times. Out of the meeting emerged the Anti-Smog Action Committee, a network of 38 local councils ready to take the discussion of smog “out of the scientific laboratories and into the hands of the people.”

This activism got the attention of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors. They demoted Gordon Larson and brought in their ace problem-solver, S. Smith Griswold, whom the New York Times described as a “tall, imposing, athletic-looking man with wavy straw-colored hair and the piercing gaze of a John Brown.” Griswold had a solid track record: he had created the county’s Department of Communications and had eased prison overcrowding by building new prisons, work done between stints in the navy during World War II and the Korean War. Now he needed to convince the public that the APCD could wage a war to abolish smog.

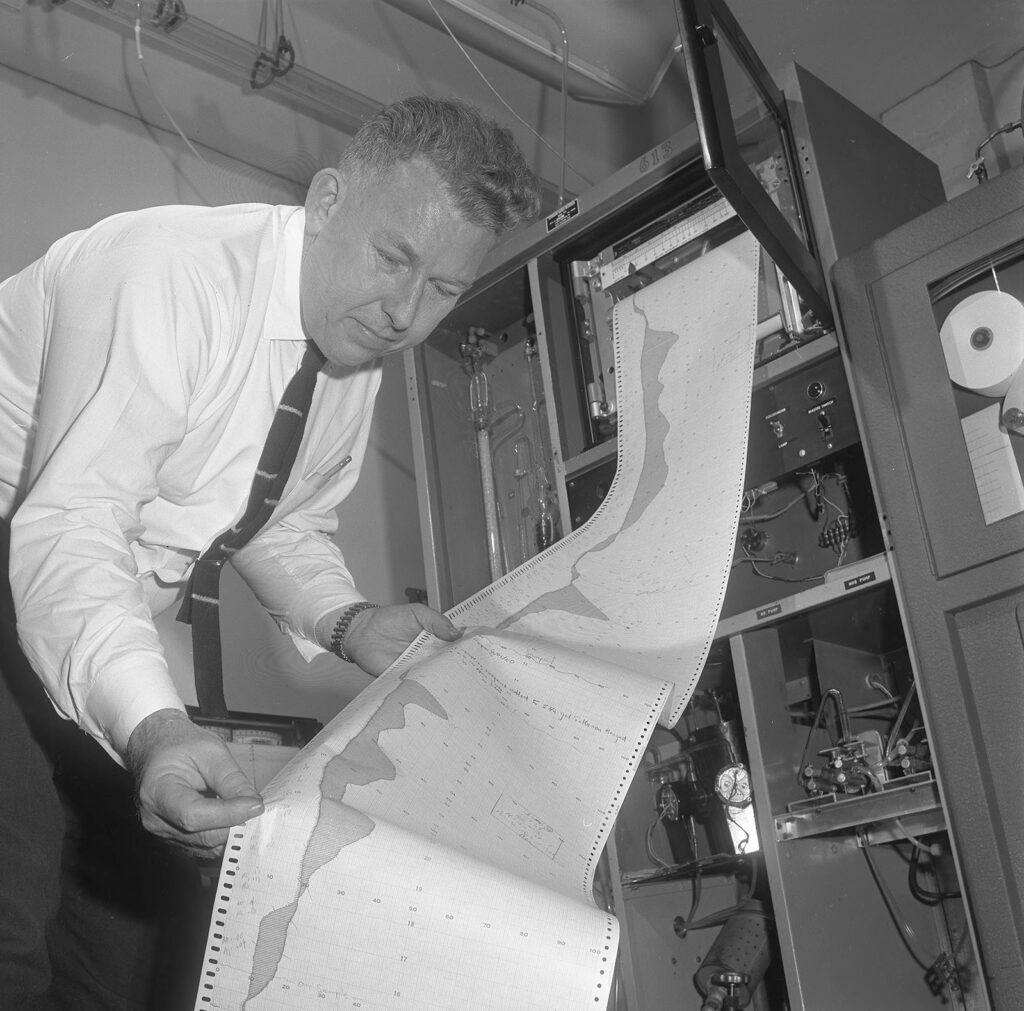

Griswold realized the APCD needed a change in approach, and that change needed to be apparent to the public. In his first month the new director proposed tighter air-pollution laws to the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, which meant banning backyard trash incinerators, requiring gasoline-vapor recovery systems at refineries and gas stations, and promoting prototypes of catalytic converters and crankcase systems for controlling auto exhaust. (Banning backyard incinerators required the county to buy land for trash dumps and to set up a public trash service, which triggered an epic fight between L.A. mayor Norris Poulson and the mob-dominated private trash haulers.) Griswold also ramped up the work of the APCD’s “striking force,” putting enforcement division officers on patrol 24 hours a day and even using helicopters and a standing air patrol to find polluters. He hired more inspectors and publicized the exponential increase in citations against industrial polluters. And he beefed up the APCD’s research staff, casting them as an “intelligence division” charged with monitoring the enemy.

Amplifying the rhetoric of war, the APCD secured permission to sound air-raid sirens and even order traffic off the county’s roads if pollutants reached dangerous levels. (While the sirens would occasionally sound in politically restive Pasadena, shutting down traffic was a step Griswold never attempted.)

Instead, Griswold launched a public education campaign to persuade residents that the invisible gases from cars and incinerators really were the main causes of smog. The APCD began a monthly newsletter illustrated with striking photographs and cartoons. Griswold and other senior APCD officials presented exhibitions and gave lectures to service clubs, women’s clubs, and other civic groups. High school and college students competed in APCD-sponsored essay contests to explain the causes of smog and to propose solutions. Radio station KABC worked with the APCD on Smog Story, a weekly 15-minute program that explained what the district was accomplishing and how residents could “help in the fight.” The APCD also staged public events, including Griswold’s ozone sauna, to attract newspaper coverage. Stories in the Los Angeles Times, an advocate for the region’s growth, made Griswold a modest celebrity. A 1959 profile described him as “ruggedly handsome” with a determined set of jaw. That same profile also prepared readers for the “long, uphill battle” against L.A.’s smog, which had been created by “the inevitable and beneficial factors of growth and progress.”

Griswold tried to convince the public that carmakers, not car owners, were the enemy. He didn’t blame local citizens for driving or area planners or developers for creating a region dependent on cars. The auto industry was quite capable of reducing smog-causing ozone and nitrogen oxide emissions, he wrote in September 1956, “if it [was] willing to turn to that end a small portion of the money and manpower that goes into making automobiles more fashionable.” As L.A.’s smog got worse, he ratcheted up his attacks on Detroit. In 1964 he described automakers as “crusted with ignorance and apathy,” adding that “everything that the industry is able to do today to control auto exhaust was possible technically 10 years ago.”

Powerful people in L.A. complemented Griswold’s efforts. A group of commercial developers and industrial leaders established the Air Pollution Foundation (APF), which commissioned research into the causes and distribution of air pollution and funded research and development work on smog-control devices for cars. Like Griswold, the APF framed smog as a technical problem best solved by automotive engineers, not by a politically active public that might call for limits to population and industrial growth or even demand public transportation.

Reframing the smog issue transformed environmental activism in Los Angeles. The Anti-Smog Action Committee petered out as a new organization emerged: Stamp Out Smog (SOS). Begun in 1958 by a group of local women, SOS soon became the most significant activist group battling smog. During the 1960s its leaders, Margaret Levee and later Afton Slade, used evocative public protests and letter-writing campaigns to focus California elected officials on the automakers’ recalcitrance.

In 1965 Griswold left L.A. for Washington, D.C., to head up abatement and control in the federal government’s office for air-pollution control. His work helped lead to the passage of the 1967 Air Quality Act, which brought the federal government into air-pollution control enforcement for the first time. His years of anti-smog work contributed to the more efficacious 1970 Clean Air Act, which mandated catalytic converters on all new cars sold in the United States after the 1975 model year.

Griswold died in 1971 after a long battle with cancer. His obituary in the New York Times recounted a line he often used in public speeches: “During the past decade the auto industry’s total investment in controlling the nation’s No. 1 air pollution problem—a blight that is costing the rest of us $11 billion a year—has consisted of less than one year’s salary of 22 of their executives.”

While Griswold was never especially famous, he more than anyone helped convince Americans that air pollution is caused by cars and not by our collective choices to build a society dependent on vast numbers of them.