During World War II, Graham Sutherland (1903–1980) served his country as an artist. His war duties kept him in England, where he focused on painting industrial scenes and the devastation faced by ordinary people. After the war Sutherland traveled to Europe and painted his first portrait; the subject was novelist W. Somerset Maugham, whom Sutherland met in France. The painting proved hugely successful and was later hung in the Tate Gallery along with many of his other works.

Sutherland became so well known a portraitist that Parliament commissioned him to paint Winston Churchill for the latter’s 80th birthday, despite the enormous political gap between the Tory prime minister and the socialist artist. At the portrait’s official unveiling in 1954 Churchill smilingly described it as “a remarkable example of modern art,” much to the amusement of his audience. But Churchill was not so amused as he pretended. Before its presentation he had a sent a letter to Sutherland stating that “the painting, however masterly in execution, is not suitable.” Indeed, the portrait was so hated by Churchill’s immediate family that it was secretly burned after the statesman’s death. Churchill himself had said it made him “look like a down-and-out drunk who has been picked out of the gutter in the Strand.”

British historian Tim Crook writes that Churchill and his family could not appreciate that Sutherland had “created a beautiful expression of Churchillian indomitability, a symbol of an old country’s defiance of all the ravages of total war, and a presentation of the sturdy and independent humility of a democratic Parliamentarian in plain dress.” Sutherland only discovered the fate of his painting in 1978 and viewed its destruction as an act of vandalism.

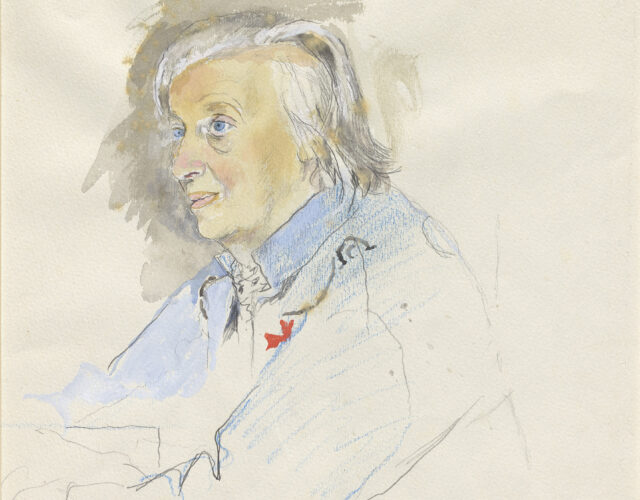

Sutherland’s paintings were generally preceded by sketches of his subject, such as the one pictured here of biochemist Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910–1994). Sutherland drew this sketch of Hodgkin in 1978.

Hodgkin was fascinated by the shape of molecules and worked with X-rays to illuminate the structure of biologically important molecules, such as penicillin, cholesterol, insulin, and vitamin B12. In 1964 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for her determinations by X-ray techniques of the structures of important biochemical substances.”

In the 1940s, soon after Hodgkin had unraveled the structure of penicillin and so made her scientific name, she taught Margaret Roberts chemistry at Oxford University. Hodgkin recalled that she was “very pleased” with Roberts as a student and even sent her a congratulatory letter in 1979 when Roberts, by then better known as Mrs. Thatcher, became prime minister of the United Kingdom. “Yours is a very remarkable achievement,” she wrote, “to be the first woman prime minister of this country and also the first scientist.”

Sutherland died in 1980, leaving his painting of Hodgkin unfinished. Only two of Sutherland’s sketches of Hodgkin are known to exist, one at the Royal Society in London and this one at the Science History Institute.