What do sesame seeds tell us about the environmental histories of the African Diaspora? How does a historian know where to start? It’s all a question of process.

1

Sesame seed pods look like the progeny of okra and edamame. They hang upright on thin stalks like fuzzy, elongated dreidels. Sometimes, scholars wonder what first attracted humans to a particular plant, such as cyanide-laced cassava. That’s unnecessary with sesame pods. Their appeal is obvious; they look like they’re holding something inside. And if their boxiness doesn’t catch people’s attention, then the sound of them rattling when ripe surely will.

2

Toasting sesame gets smoky fast. Go two or three seconds without stirring the pan, and the seeds snap, crackle, and then pop. The sound is clear and distinguishable, but watching the smoke rise also stirs the curiosity. It curls upward from the seeds, hugging the contours of the pan’s shallow edges, without any clear origin. Is the smoke coming from the seeds or the pan? Resembling wisps of carbon dioxide gas sublimating from dry ice, sesame smoke seems to skip a liquid phase and go straight from solid seed to gaseous exhaust. But that’s not at all what happens. The liquid oil is there, a raison d’être of sorts. It helps sesame survive in harsh conditions and is why its seeds made it into the hot pan. Sesame might not appear or feel as oily as an olive or avocado. Still, with close attention and steady stirring, sesame’s smoke is a signal. When we reconsider who has historically done the stirring, it becomes a fleeting analogy for sesame’s place in environmental history. Like all seeds, sesame seeds are diaspores, or plant dispersal units, which share etymological origins with diaspora. Uniquely, however, sesame was also scattered across the Americas alongside the African Diaspora.

3

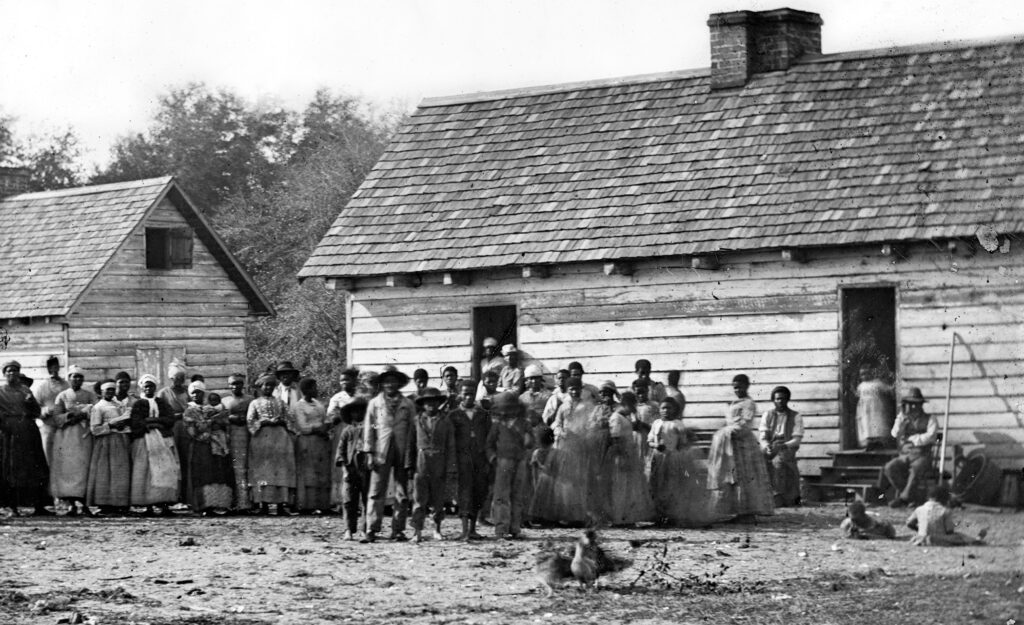

Plantations were dramatic places. Devastating landscapes of invigorating terror, for enslaved people and the environment. Plantations were dynamic and generative epicenters and engines of the modern world, its divisions of labor, its wastelands, and its unevenly accumulated wealth.

The plantation landscape was also uneven and had pockets where enslaved people could carve out marginal amounts of direction for themselves. Consider the small-scale subsistence gardening of enslaved black people and the plants they grew, like sesame. Not every sesame field was a plantation or part of one. Some were provision grounds or dooryard gardens. Ira Berlin and Philip Morgan agreed these “gardens and provision grounds permitted the elaboration of African-influenced conceptions of spatial order” where fluid and irregular boundaries could work “against the geometric and rigid European notions of order.” Sharla Fett also insisted that black enslaved gardeners liked to plant sesame at the ends of their rows to “ward off intruders.” Sesame fields could be plots wherein enslaved black folks, by nature of planting for themselves, slowly eroded the plantation power and made their lives a touch more livable.

4

To save time and space, planters extended marginal time and marginal lands to their enslaved property. To burn daylight asking black folks about their dooryard gardens and plots would have defeated the planters’ goal of extracting wealth from black life as cheaply as possible. Despite plantation owners’ efforts to ignore and discount the black lived experience, the historical record is no monolith. Try as they might to exclude us, we have black environmental history at our disposal.

Black environmental analysis is nothing new, but we now read landscapes better than ever, highlighting and underlining power and racism like we might these sentences. We can take places we know existed, such as an enslaved person’s dooryard garden, and analyze what Amani Morrison calls “black spatial affordances.” Since we know from many sources that black folks were allowed, and even encouraged, to grow sesame in their gardens, we can use the plant to trace numerous scenes of survival. One topographical sketch of Florida from 1821 noted black folks growing enough sesame to “afford luxurious repasts” of cakes, pottage, and other “composition[s] with sugar.”

Sesame, like okra and watermelon, was one of the few plants that people successfully transplanted from tropical West Africa to the more temperate climates of the U.S. South. Tropical dooryard gardens have climate affordances different from those of subtropical ones. You won’t find tamarind, plantain, or oil palm growing in Mississippi. However, sesame found a way to the rice coasts of the Carolinas. Here, observers witnessed black folks planting “their benne in the hills like beans.” Benne is what our ancestors called it.

To imagine how black folks planted sesame, it helps to consider geography, season, and time of day. In South Carolina, planting was likely at night in late spring, sometime after the rains—never before. The soil needed to be moist but not too damp. Gardening by moonlight was demanding after a long day working plantation fields. Imagining the strain on the eyes gives new meaning to planting by hand. Feeling through the soil, making knuckle-deep holes to place the seeds. Or maybe planting sesame required more faith than care. According to folklore, free black farmers sprinkled sesame seeds at the entrances of the cabin homes just like their enslaved ancestors had.

5

It’s been 30 years since Michel-Rolph Trouillot suggested silence enters the archive at four stages: “the moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history).” The archive of black environmental history suffers from all four.

In the case of sesame’s black history, planters and politicians made sources that discredited black farming practices as “shiftless and careless” and “very wasteful.” When assembling collections on sesame cultivation, their perverted perspective of black farming perverted how they documented black experiences, if at all. The uneven and biased records on sesame that appear in 19th-century agricultural, botanical, and medical journals do not tell the full story of black ecological knowledge, which materialized into practices and policies that do not value black environmental history. Luckily, those perspectives no longer have the reins on making history. We can look back, reflect, and tell different and actively unfolding black histories of sesame.

6

My late Uncle Bernie Porter lived in Beaufort, South Carolina, for decades before passing away there in 2017. At his funeral, I remember seeing his widow, Shirley Porter, and meeting his stepdaughter, Natalie Daise. I also remember feeling starstruck, because Natalie and her husband, Ron, starred in one of the most popular children’s shows for black kids from the ’90s: Gullah Gullah Island. It was another Sesame Street for us, a place where exciting black things happened. And though the Nickelodeon show was mostly shot on set in Orlando, Florida, the landscape and exterior sequences showed Beaufort, a place with sesame streets, sesame people, and sesame culture. Only, the Gullah and Geechee people of the Beaufort area and neighboring Sea Islands pronounced their sesame benne. They knew benne as well as they knew the fish, turtles, and oysters teeming through their landscape.

7

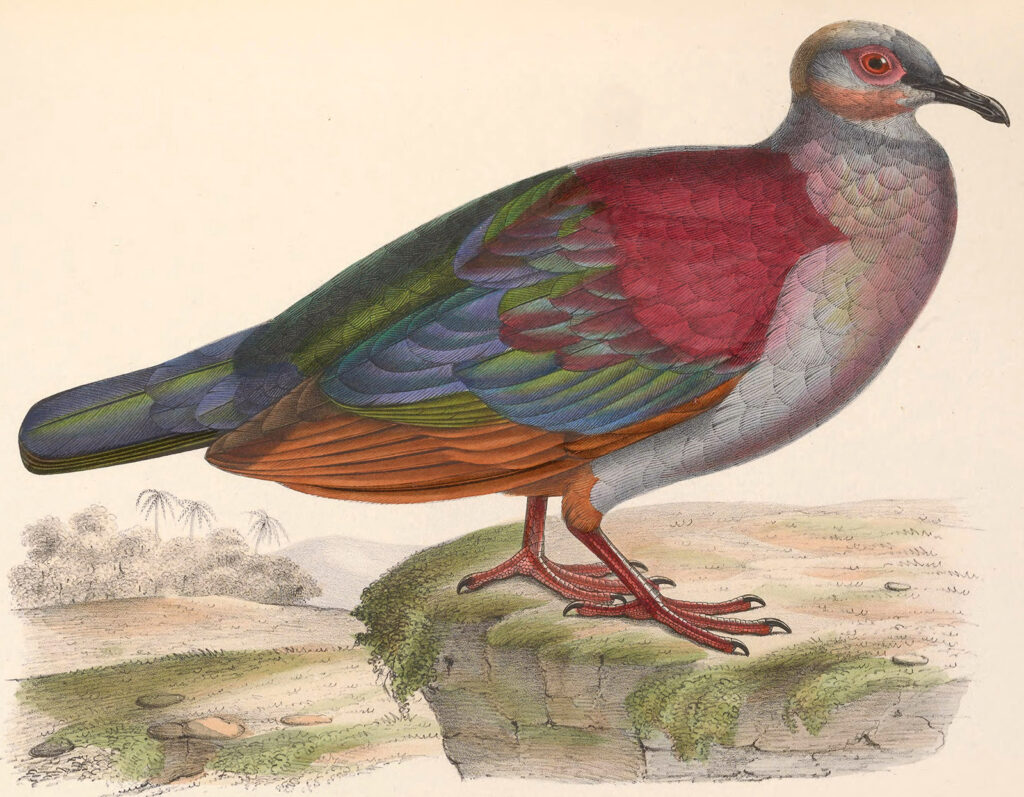

Walk a trail in the Blue Mountains and you might hear “hoo-oo hoo,” with an emphasis on the second “oo.” This is the sound of the crested quail-dove (Geotrygon versicolor), a monotypic species endemic only to Jamaica’s eastern mountain ranges. It’s a rare bird you’d likely hear before you see, if you see it at all. For obeah practitioners, the crested quail-dove’s elusive and secretive behavior earned it the name “mountain witch.”

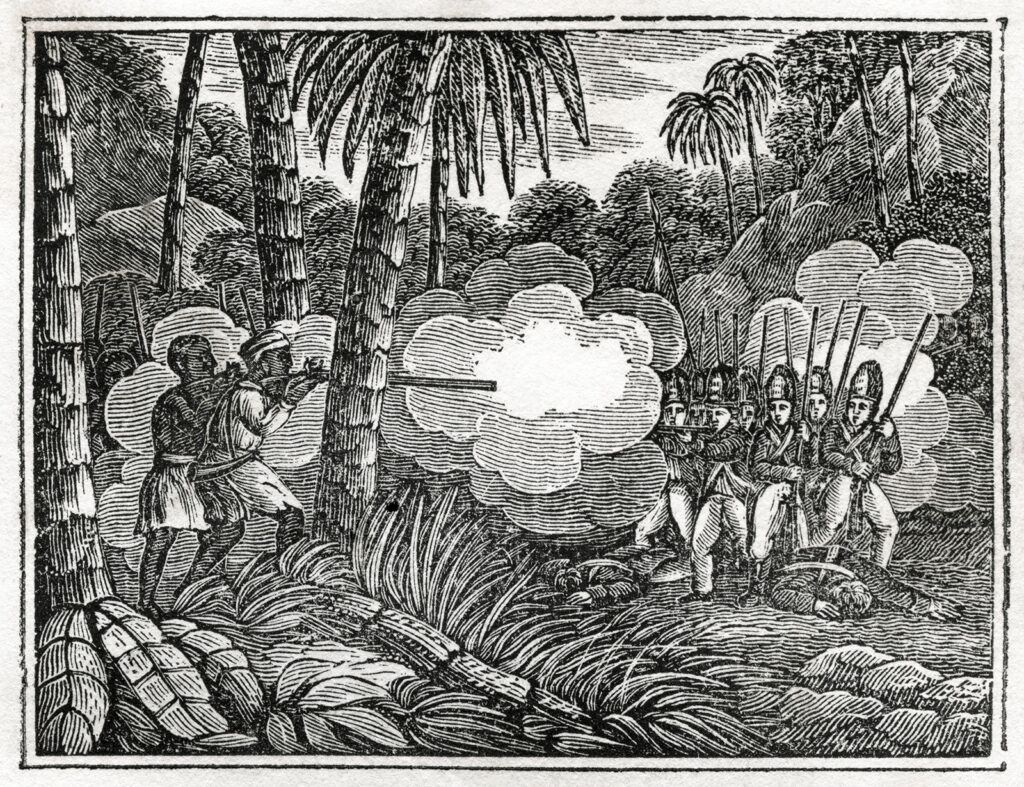

Before UNESCO designated them protected biodiversity hotspots, Taino communities and enslaved people ran away to the mountains and cloud forests to protect themselves from colonialism and slavery. They created a network of trails, hiding places, and settlements known today as the Nanny Town Heritage Route. Numerous rare flora and fauna along this route represent the afterlives of this centuries-long environmental resistance to European violence. Communities of runaway Maroons also introduced crops from the African Diaspora to the region, such as bananas, oil and coconut palm, Otaheite apple, and sesame.

Like the mountain witch, sesame held spiritual value for communities in the Blue and John Crow Mountains. Jamaican obeah practitioners tended to refer to sesame as vangloe or wangla and used it in their gardens to ward off thieves. Did the rattle of dry sesame pods discourage skulkers, or were these gardeners relying on sesame’s reputation for good luck to protect them? The limitations of colonial records and their reductive colonial perspectives leave us few definitive answers. Landscape interpretation encourages us to trace the natural and unnatural forces that shape the land, whether climate or slavery, flora and fauna or capitalism. Reading black history into landscape through an analysis of these forces makes it clearer that Sesamum indicum had many lives and relations in the black-held environments.

It’s possible to imagine other forms of good luck benne brought enslaved and free black folks. Might sesame have attracted edible doves and quails to the provision grounds and gardens of black people or the hidden landscapes of the self-emancipated? Planters have long used benne meal, a byproduct of benne oil production, as poultry feed. Did black people use benne to attract wild game? Several scientific studies and hunting journals in the early 20th century indicate that benne was particularly palatable for doves and quails during the summer. Hunters from Alabama to northwestern Florida looked for “wild occurring” benne to increase their likelihood of finding targets. A 1926 article from Game Breeder titled “Benne, A Good Southern Quail Food” not only suggested that enslaved people first brought seeds that resulted in benne running wild but that black families also continued to cultivate it in “small patches.”

Today, biochemists at Louisiana State University are adopting these historical observations as clues to further investigate the botanical legacy of black seed keepers. Since sesame attracts birds as well as bees, but never deer, could the plant have also attracted additional and much-needed calories to our enslaved ancestors’ dooryard gardens while deterring deer and hogs from other crops? Through a multi-level analysis of sesame distribution and chemical compositions in Louisiana, Dr. Jordan Dowell and his team are helping me ask better questions. For instance, how wild is “wild occurring” sesame in Louisiana? Might semi-wild sesame plants or the soils they are rooted in hold chemical signatures that can show us the geographic and historical relationships between former plantations, provision-ground crops, and local ecologies? Using scientific tools to analyze our black environmental pasts reminds me that a hunch only gets you so far. This work is full of surprises.

8

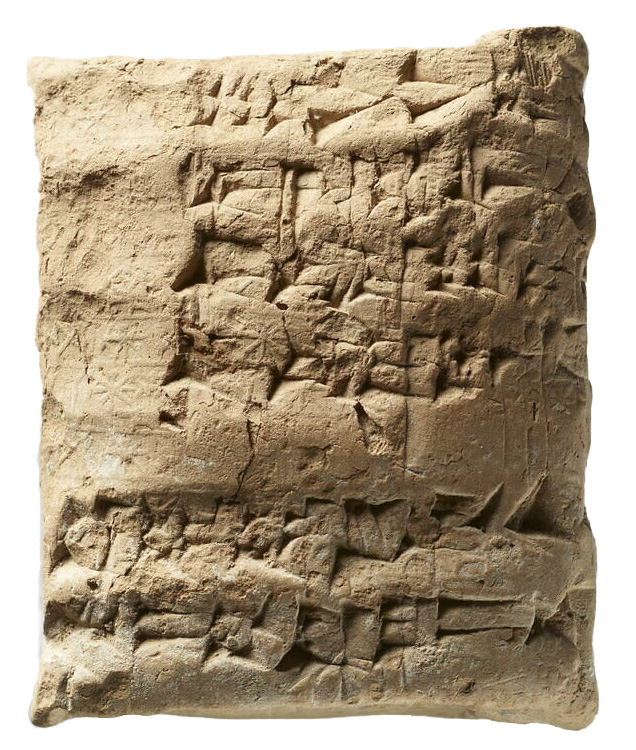

The first people who wrote the word sesame carved it in stone as cuneiform symbols. In Hammurabi’s Code, the Akkadian shape that sounded like sesame—sa-mas-sa-mu—resembled wedges in clay made by a fine, feather-like utensil. These markings described sesame as a legal tool or currency to settle debts and serve as collateral.

More than 3,500 years later, in the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina, the Gullah and Geechee people also used sesame as a legal measure to handle disputes. According to Dorothea Bedigian, the pioneering scholar of the African origins of sesame in the Americas, priests in the Sea Islands used sesame punitively. They would scatter a bag of corn on the ground for a wrongdoer to pick up grain by grain for a minor offense, a quart of rice for a grave offense, and a bag of sesame for the worst crimes. We unfortunately know little about this practice. Gullah and Geechee traditions were not fully etched into South Carolina’s record books, which can make collecting and recounting this black environmental history feel like picking up sesame from the floor.

9

White supremacy has many blind spots. When James Thacher visited a plantation in Savannah, Georgia, in 1810, he “became acquainted with benne.” But the writer from Massachusetts, like the Southern planters he visited, had a better view of how enslaved communities used benne than of how they grew it in “patches” or “gardens” accessible to them.

Planters surveilled their captive labor and jotted down notes about how enslaved people made benne oil for food, medicine, and illumination in lanterns. Several accounts witnessed how black folks boiled and mixed benne seeds into their rations of “Indian corn, which forms a nourishing food.” Sometimes, white observers witnessed black folks roasting and infusing the seeds into water like coffee. In more detail, Thacher also noticed how black folks “parch [seeds] over the fire, boil them in broths, make them into puddings, and prepare them in various other modes.” Most notably, he expressly acknowledged enslaved black folks for introducing this “fixed oil” into the “secondary catalogue of our national pharmacopoeia.”

But planters’ curiosity had its limits. They rarely listened for black goals, were oblivious to black intentions, and seldom imagined black success. What they did see was colored and distorted by racism. Moreover, since black folks felt watched, they did what they could to go unnoticed.

There’s a quiet violence to using planters’ observations to understand black enslaved life. A complicity in historical silencing. How can we move from watching black life to listening to black life? How do we do this when historical record keepers focused on black people as property with economic value, not as people with feelings and knowledge and relations beyond the plantation? Black environmental history counters silence by emphasizing ecology over economy. The study of home—oikos logos—reveals more about life and livelihoods than the management of home—oikos nomos. Focusing on ecological relations in tandem with economic ones, we can take a humble plant, such as sesame, to add to our incomplete understanding of black life in diaspora.

10

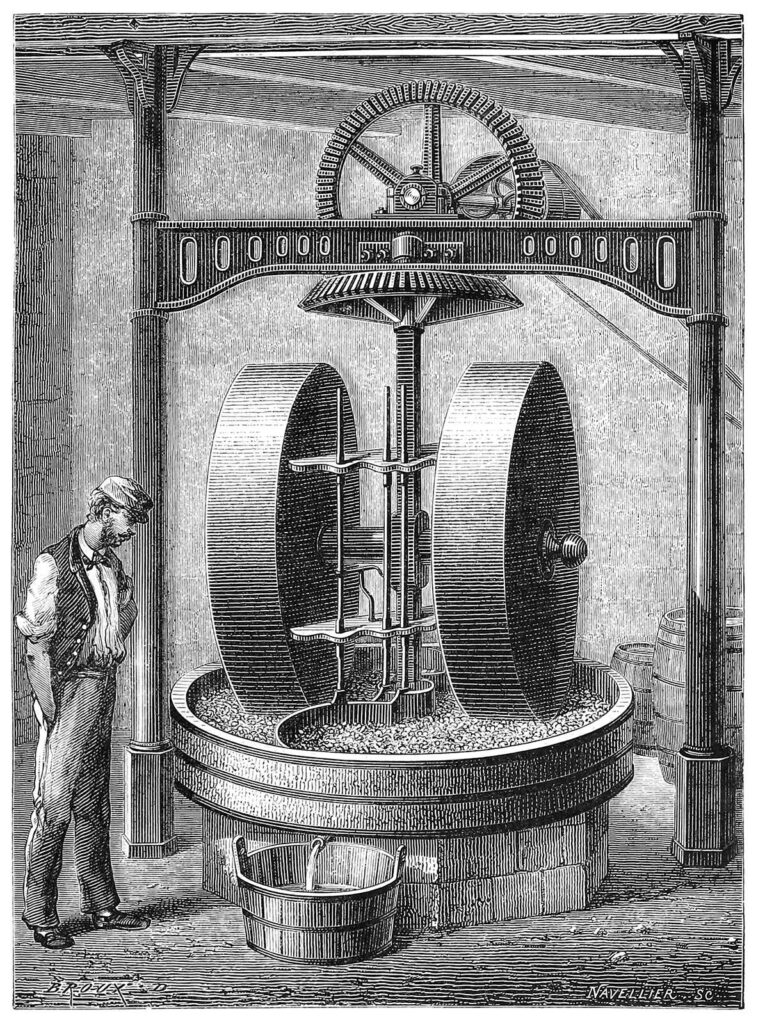

Fixed oils move a lot. They grease the motion of society at the axel, rod, and gear. Squeezing sesame seeds releases one of these dynamic, society-shaping fixed fats. It’s a base for soaps, perfumes, foods, medicines, and so much more. It can contain glycerol esters of fatty acids, which plants and animals use in a variety of ways. For instance, bioactive secondary metabolites in sesame oil have antioxidant or antibiotic properties. Phytosterols add wound-healing compounds, and the chemicals sesamol and sesamin support anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities and can reduce blood-cholesterol levels. In nature, these fixed oils also help seeds outlast difficult conditions, such as drought. That helps explain why people historically considered sesame a survivor, or poor man’s, crop. It also helps explain why so many African descendants, enslaved and emancipated, relied on sesame to survive racism.

11

Thomas Jefferson had overseers to watch his slaves, but we know he watched them, too. He watched them to learn a variety of things, especially black botanical knowledge. Jefferson’s curiosity was more intellectual than that of many planters. He studied and imitated enslaved black folks. He wanted to know what they planted, how, and why they planted it. And few of their plants piqued his interest more than sesame. From Monticello’s dooryard gardens, Jefferson learned from the enslaved how to grow sesame annually in Virginia and was encouraged to purchase and build three different sesame oil presses. Without any mention of black folks, however, he wrote in one letter that Sesamum “is among the most valuable acquisitions our country has ever made.”

12

Benjamin Waring owned 15 enslaved people the year before he died in 1811. A decade earlier, he established one of the country’s first oil mills in Columbia, South Carolina, channeling the labor and ingenuity of black folks to process oil and profits from cottonseeds, castor beans, and benne seeds. We know little about this mill besides its growing impression on the land and labor. By 1820, his son Benjamin Waring Jr. enslaved 29 people, of whom eight manufactured oils in the mill. Within decades, other planters adopted the Waring family model, and by the 1860s, companies like the Columbia Oil Company appeared to transform Columbia into a site of benne oil production. But it didn’t. Enslaved people initiated that transformation through provision grounds sprinkled around the edges of plantations. A closer look at the landscapes reveals sites of subsistence and hope, scenes of survival wherein enslaved black folks planted sesame to help make their lives more livable.

13

It was the summer of 1803, and a dysentery outbreak was sweeping through South Carolina. On July 4, James Simons wrote a letter from London about an earlier bout with dysentery in the South Carolina Lowcountry and how military officials there looked to an “old negroe woman” with “the knowledge of a remedy.” At the time, a local colonel recalled how the “plantation hospital” where this woman worked had not lost a life since she got there. In recounting the moment, Simons got the name of the remedy all wrong, calling it “Zezegery.” Still, his descriptions of the seeds that “become gelatinous of the consistency of a thin starch” leave little doubt they were benne. A Jamaican man who also witnessed this healer identified the plant as “Binnea” and said it was “cultivated in almost every plantation in this country by our negroes for their own.” Without knowing it, these men glimpsed through sesame the everyday reality of the environmental knowledge of the enslaved.

14

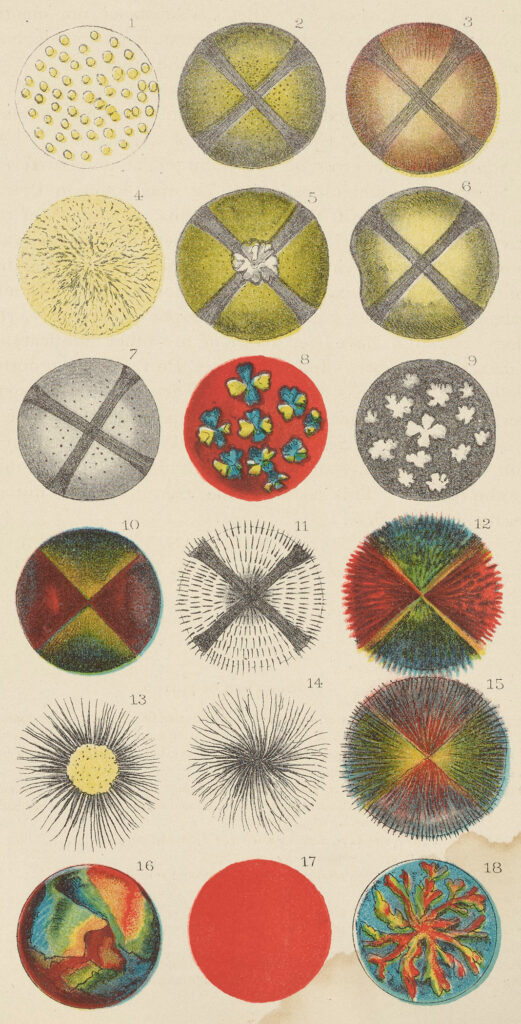

Before germ theory took hold in the late 19th century, the source of disease was usually pinned on foul smells or four capricious bodily fluids, called humors. The proportion of these humors governed both a person’s temperament and health.

Heat and cold were among the many factors that could throw the humors into imbalance and lead to sickness. People looked for cures in natural materials with cooling or warming sensations. Sorrel to get cold and dry. Peppermint for feeling hot and dry. Squash, cold and moist, helped in the summer.

The summer was especially difficult for humoral thinkers. It’s easier to warm up when it’s cold than cool down when it’s hot. This was even more true before the advent of air conditioning. Luckily for settlers in the colonial United States, enslaved people grew a mucilaginous plant that developed a reputation for solving summer complaints: benne, or sesame seed.

15

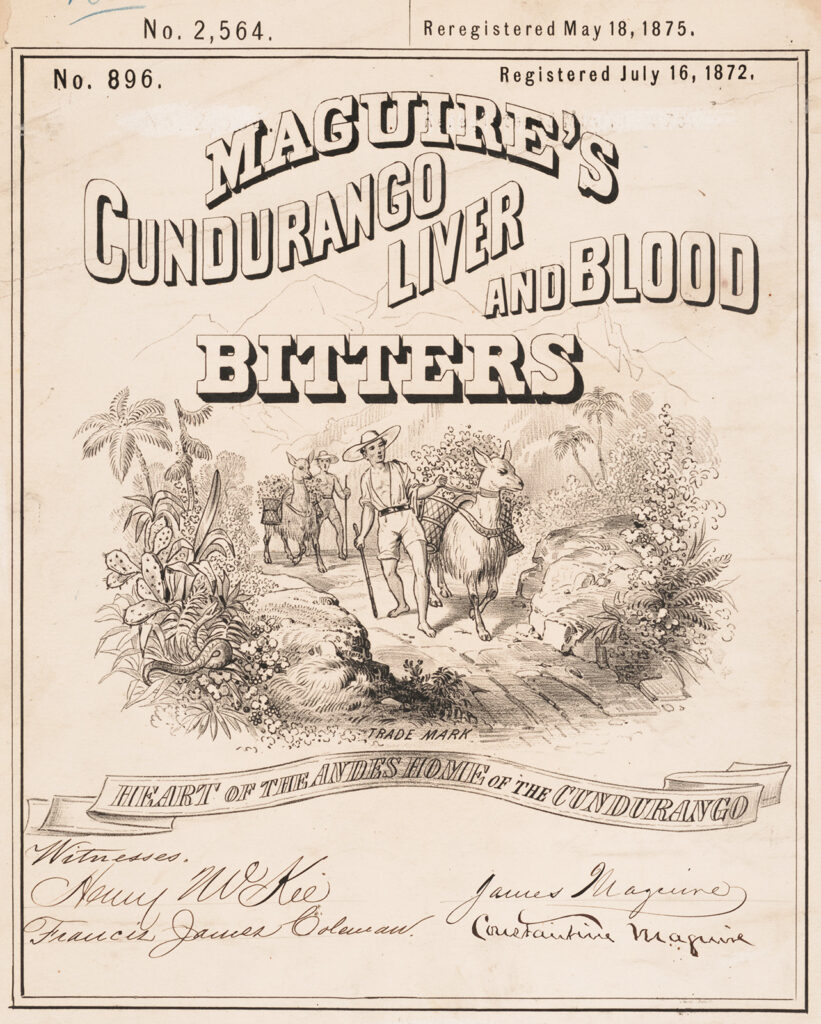

The J. & C. Maguire Medicine Company had a good run. Founded in St. Louis in 1841 by James and Constance Maguire, the Maguire Medicine Company was most popular for its benne plant concoction called Cundurango, which, according to their numerous advertisements, had “become a household word” and was “sold by all druggists for diarrhea, dysentery, and cholera-morbus.” The product started gaining traction as a preventive measure against “Asiatic Cholera” during an outbreak in 1849. It really picked up pace during times of war. In a 1900 advertisement titled “A Veteran of Three Wars,” the company suggested that “benne plant cured thousands of soldiers during the great civil war” as well as helped efforts in the Philippines and Puerto Rico during the war against Spain.

Perhaps the company didn’t mention the black origins of benne in the United States so as to not discredit themselves to white, racist audiences. In any case, by 1918 the American Medical Association discredited them entirely for being “false and fraudulent” and for containing a “habit-forming” amount of morphine. The examples of misrepresentations and appropriations of benne by non-black people are many.

16

Nineteenth-century dairymen, as they called themselves, were a weary bunch. Always concerned about some “adulterant” replacing their cash cow: butter. They feared various kinds of fatty and slick substances—from olive oil, to coconuts, to lard—but their public enemy number one was oleomargarine. No other 19th-century industry had more inventors and patents than the margarine industry. Named for the pearl-like crystallization of margaric acid first isolated in France in 1813 and transformed into margarine in France in 1869, margarine engendered in dairymen an angst echoed in the call for “freedom fries” in 2003.

In defense of their cows and their nation, dairymen called margarine all kinds of disparaging names, suggesting that it was unhealthy, unnatural, and unpatriotic. They filled countless newspaper columns and courtrooms with catchy pleas to save the nation, traditional values, and white supremacy. This was especially true in 1884 when seemingly every newspaper reported on what dairymen called “bogus butter,” an oleomargarine made with the sesame seed of black folks. They gave credit to black farmers for introducing the plant to the United States, but only to suggest that black people and their foreign seeds were bad for business and their white consumer base. Little did they know that sesame seeds, like margarine, were already part of the nation’s diet because of black farming history.

17

Sesame hides in plain sight in Puerto Rico. It’s in funchi criollo, an Afro-Puerto Rican soup made with sesame paste. Sesame’s subtle sweetness and layered nuttiness make it a common component in sweets like gofio de ajonjolí, popular mampostial candy bars, and the pilones de ajonjolí lollipops that resemble Afro-Trinidadian jawbreakers called benne balls. Look closely, and you might even find sesame in Boricua versions of horchata, a drink, like sesame, with origins in West Africa. It’s no small wonder agricultural surveys of small-scale sesame cultivation in the early 20th century noted sesame as peasant food “carried on mostly as an incidental crop intermix with corn, beans, and bananas,” in sugar-growing districts after slavery gave way to sharecropping.

18

In the 1950s and 1960s, it was common for white cooks experimenting with sesame to acknowledge how slavery brought the seed to the United States. Look at the discourse on sesame today, however, and you might see much less nuance than in the past. Few essays today on growing or cooking with sesame mention that enslaved Africans and their descendants introduced the plant to the Americas. But comb through the rising acclaim for sesame in 20th-century U.S. newspapers, and you find few recipes or exposés that do not mention sesame’s relationship with slavery. After Mrs. Bernard Alexander Koteen of Washington, D.C., won a $25,000 national baking contest in 1954 for her “open sesame pie,” scores of reporters tried to shed light on this “new” craze for sesame. They noted the seeds’ past in any number of ways: “introduced by slaves,” “carried seeds in their pockets,” and “a handful of sesame seeds.” They remind us that the past isn’t always more silent than today. Silence comes in waves.

19

For at least 60 years, my Nana has cared for an heirloom cast iron plant (Aspidistra elatior) that her mother originally received from her grandfather. Her mother, my great-grandmother, Winona, nurtured this low-maintenance plant for decades to honor and remember her father, my great-great-grandfather. My Nana calls it her “grandaddy’s plant.” She speaks to most of her plants, but when she walks past the Aspidistra, she says, “Good morning, granddaddy’s plant,” or more directly, “Good morning, grandaddy.” In caring for this heirloom, she cares for herself. It gives her a sense of pride and comfort. It also gives her a sense of hope and faith, which is not historically uncommon for black gardeners across the diaspora.

My Nana does not remember any benne seed on the family land or in her garden. Her brother, my Uncle Lefty, does not recall growing any either. He never saw his parents or uncles or grandparents growing anything resembling sesame. Perhaps our family land in Snow Hill, Maryland, was too far north for sesame to grow well. Their sister, my Aunt Shirley, considered the geographic limits of sesame but also vaguely remembers growing an “Asian plant” for good luck in her gardens in Northwest Philadelphia. Did she grow benne seed for good luck or did she grow something else? Whatever the answer, she nurtured a botany of faith, much like her sister, my Nana, and the black folks who have grown sesame for millennia.

20

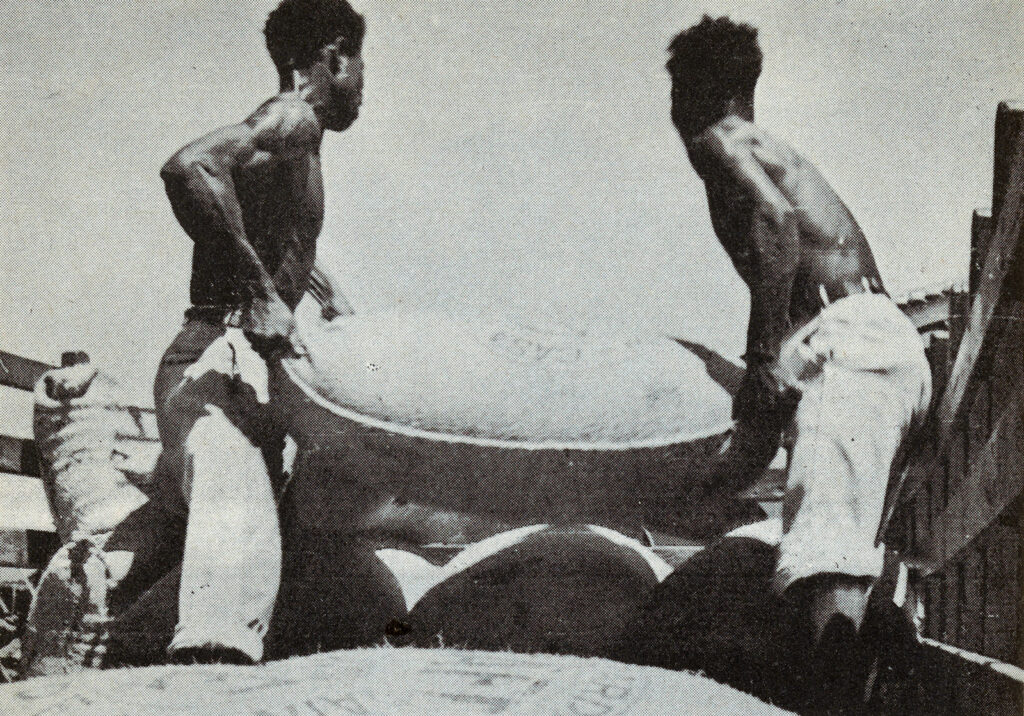

Harvesting sesame in rural Ghana is a dry-season activity. On Ekua’s family land, harvesting is perfect for cloudless days when only the occasional mango tree or distant oil palm grove breaks the clear blue horizon. Cloudless weeks are even better because after carefully cutting and bundling mature stalks into sheaves, they’ll need to sun dry 20 to 40 days before the seeds are ready to fall out. Some will fall out if you tip over the stalks, but not as readily as they will once desiccated. Once the leaves begin to fall off and the seed pods crack open slightly, you’re ready to harvest. Lay out a tarp under a large, tire-sized bowl and tip over the bundles to release the seeds into the bowl. Shake and pound each sheaf into the bowl to ensure all the seeds fall out. Don’t worry about seeds missing the bowl or pods entering the bowl; the tarp will catch them. You’ll sift out all the unwanted materials next. Sift, sift, and sift again. Then you’re ready to clean.

Harvesting sesame on the Ankuma family farm in Ghana.

Courtesy Ekua Ankuma

Ekua’s return to Ghana to produce sesame oil was born from her desire to partner with and learn from her father. Their company, Nature’s Essentials, was born in Nyakrom, a farming community in southern Ghana about 100 kilometers west of Accra. It’s a place of oil palm, cassava, and mangoes, best known for cacao. But its climate is also great for sesame. With the encouragement of a family friend and inspiration from the women who have traditionally farmed sesame in Ghana, Ekua entered the business of planting, weeding, harvesting, cleaning, and marketing sesame. Since Ghanaians prefer to use the seeds in sweets or soups rather than as oil, local distribution has proven difficult. Educating customers has been an obstacle in the long game of informing economic strategies with time-honored values in mind. For Ekua, reinvesting in farmers like her father is about integrating lessons from their indigenous knowledge of how to grow and produce local crops into future economic development. Without mincing words, she ended our interview insisting that “farmers are integral to the success of our communities” and “another byproduct of reinvesting in farmers is maintaining indigenous knowledge . . . through generations.”

21

As we stood in front of two massive pines on former plantation land in Washington, D.C., a beloved landscape historian and architect told me that the Piscataway people of the area believed that two paralleling trees could serve as a portal into another world. Perhaps a world apart from the spread of settler colonialism and slavery. I wondered if the enslaved black people on this land saw these same trees and imagined something similar. Maybe another plant could do that. Perhaps the sound of ripening sesame seeds rattling in their pods conjured up the thoughts and realities of a more livable world for black folks. Sesame, which goes by juljulan in Arabic, after the words juljul for “small bell” and jaljala for “sound” or “echo,” creates its own soundscape, an acoustic space of possibilities. Walk down the narrow dirt road between fields of a sesame farm in Ghana or through a plot in Beaufort, South Carolina—engulfed by millions of jingling seeds, imagine them telling you that they’re here and ready, and they’ve always been here and ready for us.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Dorothea Bedigian for her pioneering work; Raven Ashlee, Jori Lewis, and Bathsheba Demuth for reading earlier drafts; and Janet Malcolm (1934–2021) and her 1994 essay “Forty-One False Starts” for inspiring the essay’s structure. Lastly, thanks to Ekua and Araba Ankuma for sharing photos, videos, and stories from their sesame fields in Ghana.

Support for this article is provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage as part of the Science History Institute’s latest exhibition, Lunchtime: The History of Science on the School Food Tray.