In 1972 a group of psychiatrists and mental health workers from around the world toured the home of a traditional healer in a dusty village near Ibadan, Nigeria. Inside his mud hut animal skulls floated in jars, and dried plants lined the shelves. Outside, sitting on the ground next to a dirt road, was one of the healer’s patients—a woman with her ankle chained to a post.

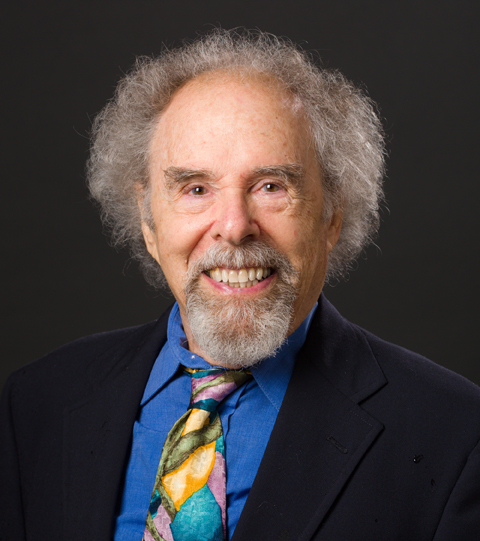

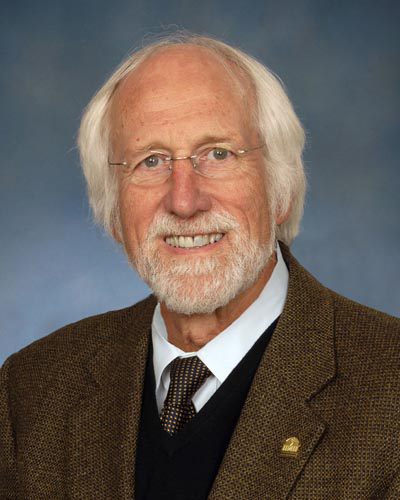

Nearly 50 years later the scene remains vivid for two American psychiatrists. “My first thought was how horrible that was, because it was like she was a slave, and she was being exposed to all these people who were walking by along the road,” says John Strauss, now an emeritus professor of psychiatry at Yale University. Will Carpenter, a professor at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center outside of Baltimore, also remembers her: “It was upsetting to see, though she didn’t seem to be suffering from it.”

The men were in Nigeria as part of the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia (IPSS), which met annually in one of the nine participating countries. That year it was Nigeria’s turn to host. Strauss and Carpenter, two young psychiatrists at the start of their careers, represented the American delegation. To Strauss a sense of mystery and peril permeated the proceedings. Nigeria had just switched car traffic from the left to the right lane, and the ensuing crashes left the highways splattered with bloodstains. The researchers met at a hotel encircled by strange, stalagmite-like termite mounds, in unrelenting heat and humidity; beyond the refuge of the hotel a cholera epidemic menaced the locals.

But the encounter with the chained woman pushed both Strauss and Carpenter to rethink conditions for the mentally ill back in the United States. After watching her for a while they realized that passersby would stop and talk with her, and she would talk with them. In contrast, in the United States people with schizophrenia often faced their illness alone, cut off from their families and communities. “Was she better off than somebody who goes to a state hospital in the U.S., who is totally isolated from their community and from people not involved with mental illness?” Strauss asks. “I don’t know what the answer was, but it wasn’t clear.”

In 1966 the World Health Organization (WHO) created the IPSS to answer a global question: is schizophrenia a condition found in different countries and cultures? At the time, methods of diagnosis varied widely, such that a person deemed schizophrenic in New York City would likely be diagnosed with manic depression in London. Developing countries, where psychiatry was a novelty, lacked a clear idea about the types of mental illness within their populations. Meanwhile, psychiatrists were becoming aware of cultural differences—in what was perceived as normal behavior and in how people expressed their illness—leading some to suggest that schizophrenia was an invention of Western societies.

The IPSS gathered together psychiatrists from nine countries—the United States, the United Kingdom, Denmark, Colombia, India, Nigeria, Taiwan, Czechoslovakia, and the Soviet Union—who over the course of a decade diagnosed, followed, and analyzed more than a thousand patients. This international study was the first of its kind in terms of scale, scope, and standardized methodology. Without email, fax, or desktop computers the scientists amassed two million pieces of data while buffeted by political tensions, grueling travel, and their own assumptions about the nature of schizophrenia. What were the disorder’s defining features? Could someone with schizophrenia actually get better? Would people in developed countries fare better than those in developing ones?

Ultimately, the IPSS researchers found schizophrenia in every place they looked, revealing the condition to be a fraught byway of human experience. And yet for the Americans the process raised the question of whether a unified concept of schizophrenia is the most useful way to think about the disorder. That question lingers to this day, as development of new therapies has stalled.

Crummy Science

Today schizophrenia is recognized as a disorder in which a person is beset by psychotic symptoms—among them hallucinations and strange, delusionary beliefs; apathy; and dramatic disconnects in their thinking. It typically strikes in young adulthood from causes that are still unclear but involve genetics, environment, or both. People with schizophrenia vary a great deal in how they express their illness. For example, some are severely psychotic but with the help of antipsychotic drugs can manage to go to work; others are paralyzed by a lack of will and cannot get out of bed.

Doctors have traveled a twisted path to arrive at the present-day conception of schizophrenia. Nineteenth-century asylums held people labeled insane but surely included people with schizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses, as well as those with intellectual disabilities or even deafness. Today we see these various conditions as distinct, but at the time it was unclear how to differentiate them.

Part of the problem was deciding on a workable principle by which to classify insanity. Should it be classified according to its causes? (Even today the causes of mental illness remain hazy for the most part.) Should it be classified according to its treatments? (The introduction of penicillin cleaved off insanity caused by a syphilis infection from the rest of the psychotic illnesses.) Could classifying according to outward signs work?

A German psychiatrist named Emil Kraepelin tried the last of these approaches, relying on observable features to define a syndrome. Unlike a disease, for which a cause is known, a syndrome groups together similar symptoms while acknowledging the syndrome may arise from different causes.

In 1899 Kraepelin described a psychotic illness that is now recognized as schizophrenia, though he didn’t call it that. The disease displayed itself through three categories of symptoms: in addition to psychosis it was marked by disorganized thought as well as a profound lack of motivation (or as he put it, “a weakening of the well-springs of volition”), and a progressive mental decline. He named the illness “dementia praecox” because it seemed a kind of premature senility.

A Swiss contemporary of Kraepelin’s, Eugen Bleuler, also recognized this syndrome, though he did not agree that mental deterioration was an essential feature. In 1908 he renamed it “schizophrenia” to emphasize the mental disconnects he felt were at its core—schisms between thoughts themselves, between thought and emotion, and between thought and behavior. (Schizophrenia does not refer to split personalities as many people think.)

Though Bleuler’s concept of schizophrenia prevailed, psychiatrists had a lot of leeway in how they interpreted it. In 1959 German psychiatrist Kurt Schneider attempted something more incisive: he specified symptoms that by themselves could differentiate schizophrenia from other psychotic illnesses. These included hearing voices and having unusual beliefs about thought ownership, such as feeling others could read one’s mind or insert and withdraw thoughts from one’s mind. These and other “first-rank” symptoms elevated the conspicuous, disturbing distortions of reality as most important for a schizophrenia diagnosis.

But did differentiating schizophrenia from other conditions even matter? At the time, many American psychiatrists embraced an understanding of mental illness that saw people’s relationships and experiences as central to their illness and treatment. This “psychodynamic” view held that personalized therapy aimed at resolving a person’s inner conflicts was the path back to health regardless of the diagnosis.

This ambivalence about diagnosis, coupled with a blithe reliance on first-rank symptoms, made for a particularly lax definition of schizophrenia in the United States.

In other countries criteria for a schizophrenia diagnosis were stricter and aligned more closely to the original symptoms set forth by Kraepelin and Bleuler. Yet the exact rules for diagnosis differed from center to center, which meant that a psychiatrist in Germany could not be sure what the term schizophrenia referred to outside of his or her own institution, let alone in another country.

“People did not realize how crummy the science was about diagnosis,” Strauss says, shaking his white, frizzy hair as he remembers those unruly times. In a tone of disbelief he recalls his stint as a medical student in the 1950s, asking a supervisor why a particular patient was considered to have schizophrenia. The reply: “Because he’s in this hospital.”

Mission Possible?

Amid this muddle a Taiwanese psychiatrist argued for a survey of mental illnesses around the globe. As a young man attending medical school in Japan in the 1940s, Tsung-yi Lin was drawn to psychiatry, sensing new scientific frontiers in understanding the mind and brain. He returned to Taiwan to establish the country’s first mental health program. Lin applied the methods of epidemiology—up until then reserved for infectious diseases—to psychiatric conditions, going out into the field to interview people in rural and urban communities alike. He was struck by how some people could seem perfectly well in their bodies yet be ravaged by mental illness. He came to believe mental health was an essential component of public health and would say, “No mental health, no health.”

Lin wondered what insights about psychiatric disorders could be gained by comparing practices in different countries. When he was named director of mental health at WHO in 1964 (a post he held until 1969), Lin went to work building on this idea. From his new, still sparsely furnished office in Geneva, and with financial help from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health and WHO, Lin recruited a group of psychiatrists from countries spanning a range of cultures, socioeconomic development, and governance: the IPSS was born.

The mission seemed simple enough: see if cases of schizophrenia could be found in the nine different countries, and check in with the patients two years and then five years later to see how they were doing. Schizophrenia was chosen because it had good odds of being recognized in different settings, given its severe and long-lasting nature.

But difficulties strained the enterprise from the get-go. At one of the first meetings doctors were shown a film of a patient interview and told to write down their diagnosis without showing it to others. The audience participated reluctantly, feeling the exercise to be too basic; they were, after all, experts in identifying these things. But the results were shocking: some had diagnosed schizophrenia; others, manic depression; still others, affective psychosis.

“It was a situation in which you think a label means the same thing for everybody, but it didn’t,” Strauss remembers.

The psychiatrists soon recognized another challenge: they carried with them cultural differences in what did and did not constitute normal behavior. For example, a facial expression an American psychiatrist perceived as blank might be seen as serene by a Taiwanese researcher. In addition, different cultures incubated different behaviors; a study at the time reported how in Hawaii white people with schizophrenia ranked higher in belligerence, depression, and anxiety compared with their Japanese counterparts, who displayed more inappropriate and withdrawn behavior. Given these differences, could psychiatrists from around the world—from the free, state-supported clinics in Denmark; to a single center amid 17 million people in rural India; to the crumbling psychiatric facilities in Soviet-occupied Czechoslovakia—ever see schizophrenia in the same way?

Mental Measurements

Then, as now, a schizophrenia diagnosis is based solely on behavior; there are no precise biological markers for mental illnesses as there are for heart disease or diabetes. Psychiatrists rely on what patients tell them and what they can observe. Thus, the IPSS’s main task was to devise a common language for describing a patient’s symptoms that would work across cultures. Once patients were evaluated using this standardized method, the psychiatrists would assign a diagnosis. The IPSS could then determine how much people diagnosed with schizophrenia resembled each other around the world.

For the evaluation the IPSS reworked an assessment developed by John Wing, the chief investigator from the United Kingdom. Clever and acerbic, Wing had recognized the need for a common, precise language to describe a person’s mental state. His evaluation consisted of 360 items that a doctor observed or asked the patient about, then ranked on a scale of 0 to 2 in terms of severity. These items touched on such things as concentration, mood, anxiety, obsessions, perceptual anomalies, delusions, and speech. This catalog of a person’s current mental state provided each of the IPSS investigators with the same raw material to use when making a diagnosis.

Wing’s evaluation permitted rephrasing in language familiar to the patients. Yet changes were still needed to make the assessment cross-culturally relevant. For example, patients from rural communities were often confused by the question “How often do you see your friends?” because they saw them every day in their small, tight-knit villages. In Taiwan, where mental illness was traditionally seen as a possession by evil spirits, patients became exasperated by the endless questions about symptoms. Translations of the test into seven non-English languages encountered words with no easy equivalent. For example, when assessing for delusions of control, the English version asked, “[Do you feel] as though you were an automaton, robot (zombie), marionette, puppet, without a will of your own?” In Yoruba, a Nigerian language, this question became “[Do you feel] as if you were an image without your own will (fairies, image, and others)?” In Czech it was “[Do you feel] as if you would be some automaton, robot-machines (a plaything, a doll)?”

Psychiatrists are trained to count something as a symptom of illness only if it is causing distress or disability to a person and if it is outside the norms of their particular subculture. Thus, the IPSS left ranking each item up to the individual psychiatrists; however, this accommodation for cultural differences could chip away at the chance of finding a shared concept of schizophrenia. For example, one of the evaluation’s questions was “Can God communicate with you?” A Czech psychiatrist in the IPSS wrote to Lin about this question, noting that “many people believe God can communicate with them, but it is a matter of faith, not psychopathology.”

Strauss, who was fresh from his psychiatry residency when tapped to head the American branch of the IPSS, had been trained within the highly individualized psychodynamic framework. For him the whole idea of a standardized evaluation was outrageous. “To talk with somebody and make little check marks on a form was just unthinkable,” he says. But he came to see it as useful, like a musical scale that provides a basic structure to a piece of music.

“In psychiatry, finding something solid is hard, but that evaluation was pretty solid in terms of identifying patient symptoms,” he admits.

The psychiatrists began to enter people into the study in 1968. In one year they accumulated 1,202 patients with signs of psychosis, approximately 130 from each of the nine participating countries. Data showed that when patients were assessed by two different psychiatrists, their scores were similar—a measure of the evaluation’s reliability.

One pair of researchers, however, had reliability that was too high: the two Soviet doctors gave identical scores on hundreds of evaluation items, suggesting their ratings were not done independently. Carpenter, who worked closely with Strauss on the IPSS, remembers this issue clearly because it created problems for the data analysis.

“Maybe if you are the junior Communist, you don’t want to make a different rating from your senior,” he suggests. “There’s no way it could be done independently and [they could] agree almost every time.”

Still, the Soviet scores were added to the rest, which, even by today’s standards, amounted to an immense data set. Beyond the 360 items in Wing’s evaluation the researchers also obtained information on a patient’s psychiatric history, social function, and physical and neurological conditions. This added up to about 1,600 pieces of information per patient, giving the IPSS two million data points to contend with. After a patient was interviewed, the sheets of results would be sent to WHO headquarters in thick packets. There a coder entered the data into a master file by hand, onto paper at first, and then as computers became available, onto punch cards, eventually totaling 20,000 cards for all IPSS patients. It could take more than six weeks to transfer the data for a single patient.

Core Consensus

The standardized evaluations gave each psychiatrist the same kind of raw material for the next step: diagnosis. At the time, methods of diagnosis varied, and no one knew whether those diagnosed with schizophrenia would exhibit similar symptoms. Some IPSS members came from psychiatrist-rich countries that had their own rules for diagnosis; others were the only psychiatrists for hundreds of miles, and without colleagues to help maintain standards, their methods were vulnerable to drift. The Americans and Soviets had looser criteria, and in the Russians’ case they were rumored to be broad enough to occasionally include political dissidents.

The IPSS psychiatrists diagnosed schizophrenia in 811 of their original 1,202 patients with psychosis, in similar numbers from each country. Still, these findings did not indicate that schizophrenia occurred with the same frequency around the world. (Incidence was outside the study’s scope.) But they did show that no one country was loath to diagnose schizophrenia, nor was any country seemingly overdiagnosing the condition. More to the point given the standardized evaluations, the IPSS could see whether a distinctive profile of symptoms emerged. And one did. People diagnosed with schizophrenia had several symptoms in common regardless of origin: a lack of insight about their illness, auditory hallucinations, harmless events being perceived as extremely significant, suspiciousness, flat expressions, and delusions of persecution. For the first time it seemed a schizophrenia label could refer to the same thing around the world.

To address any differences in methods of diagnosis, researchers fed symptom data into a computer program that applied a fixed set of rules and then output a diagnosis—no fudging allowed. The computer diagnoses agreed with 63% of the researchers’ schizophrenia diagnoses, suggesting that for a majority of cases IPSS psychiatrists were using equivalent and specific rules for diagnosis.

The IPSS consensus meant that researchers around the world could share their findings, confident that they were talking about the same thing.

“[The results] demonstrated that you can train people to see the same problem and call it the same name in different cultures,” says Norman Sartorius, a Croatian psychiatrist who led the IPSS beginning in 1969.

The results also pointed to a fundamental truth: because schizophrenia is found everywhere, it is somehow linked to humans and their biology. But a question remained: did people with schizophrenia fare better in some societies than in others?

Far-Flung Follow-Up

If the IPSS researchers wanted to know what environments offered better outcomes for their schizophrenia patients, they first had to find them. It turned out that locating the original patients for follow-up assessments was not easy. While Denmark had a national registry that made it straightforward to track down a person’s address, other countries had no such lists. Researchers braved monsoons in India and encountered renamed streets in Colombia and a lack of house numbers in Nigeria. In Taiwan, if a person had moved, the researchers could usually get information about their whereabouts from family, friends, or former neighbors; in the United States, however, people with schizophrenia often had only wisps of a social network, which made them harder to find.

At the annual IPSS meetings members would brainstorm solutions to these difficulties. But there were also tensions among the researchers, not always confined to science. Carpenter remembers that at one meeting after the Soviet crackdown on the Prague Spring, the Czech psychiatrist complained that his group didn’t have the manpower to do the follow-ups. When someone suggested that he use social workers instead of psychiatrists to do the work, the Czech doctor deadpanned in front of his Russian counterparts: “You don’t understand. We’re a Communist country. There are no social workers here because there are no social problems.”

Ultimately 1,079 of the 1,202 IPSS patients were found and assessed at the two-year mark. The presumption was that those in developed countries, with better medical services, better roads by which to access these services, and thriving psychiatry practices, would be in better condition than those in impoverished countries with high infant mortality, few hospitals, and even fewer psychiatrists.

This presumption was wrong.

It was a “great surprise,” Sartorius says. “Denmark was a model of a democratic country, with openness and protection of human rights, treatment, and social insurance. Services were available to everybody and were given freely. So you would expect they would be doing much better than the poor people in Nigeria or India. But it was in fact the developing countries that were doing better.”

People with schizophrenia did best in Nigeria: 57% of the patients had the optimal outcome, spending little time in psychosis and living without severe social impairment; in India 48% had this outcome. But in Denmark only 6% did. At the opposite end of the scale, encompassing about 30% of patients from Denmark, the United Kingdom, and Czechoslovakia, were those living in a fog of unrelenting psychosis.

The researchers wrestled with these results, which were reconfirmed at the five-year follow-up. One possible explanation was sampling error: maybe those whose relatives went to the trouble of bringing them to a hospital in a developing country had symptoms that boded well for their future. (Today researchers recognize that people with disruptive and aggressive behavior tend to fare better—finding work, living independently, and maintaining connections with friends and family—than those with low emotion and a crushing lack of motivation.)

Perhaps developing countries offered a friendlier setting for people with schizophrenia. Families lived together, and the economies relied on agriculture, which offered unskilled jobs. In rural India, for example, a person with schizophrenia could be in charge of watching a small herd of cattle. Though considered children’s work, the job usefully contributed to the family household and provided opportunities for those with schizophrenia to engage with the community.

“Maybe there were fewer critical comments in those settings,” Sartorius suggests. “Maybe they were left in peace a little bit more. They were not asked to get up at 9 o’clock every day and go to work. They were just left to recover slowly. We don’t know to this day exactly what are the reasons that made the prognosis so much better.”

Over time these country-to-country differences have diminished. Maybe this should not be a surprise, as the world has become more interconnected and its population drifts from fields to cities.

The range of outcomes found by the IPSS also shone a light on another presumption about schizophrenia. At the time, many psychiatrists felt that a defining feature of the illness was a debilitating, downhill course. If someone got better, the thinking went, then the original diagnosis of schizophrenia had been a mistake. It’s an idea that persists.

Carpenter and Strauss remember taking some heat about this from the U.K. contingent, which suspected that any good outcomes in the American cohort were a sign that the two psychiatrists didn’t know how to properly diagnose schizophrenia. Yet when Carpenter and Strauss reanalyzed their data, they found that no matter what method they used, they always got some patients who did well and others who did poorly. Sartorius, the former IPSS director, grants that some investigators may have believed that patients who improved were misdiagnosed to begin with, but he argues it didn’t taint the IPSS results. “When the disease started, our patients were the same; then as the years went by, we saw differences,” he says.

Seeds of Deconstruction

Back in their tiny office in Washington, D.C., Strauss and Carpenter, along with statistician John Bartko, published three papers in 1974 that summarized what they had learned after the two-year follow-up.

“I think preparing those papers helped me figure out what I really thought,” Carpenter says.

Though the IPSS identified a concept of schizophrenia shared around the globe, some of the results left the Americans thinking the disorder might be better understood through its component parts. The process of sifting through the data revealed that some symptoms were associated with better outcomes than others.

For example, people with hyperactivity, moodiness, and delusions of persecution had a greater probability of a good outcome than those marked by social withdrawal, an expressionless manner, and a change in interests. The Americans also found “loose links” in their cohort: the ability to work before illness struck, for example, boded well for employment after. These connections with outcome suggested there were different mechanisms afoot in schizophrenia. In the last of the three 1974 papers, the researchers called for deconstructing schizophrenia to understand its origins and to find treatments.

This deconstruction idea fits with the original syndrome concept of schizophrenia, which allows that people may have the disorder for different reasons, different brain processes may be involved, and different treatments may be required. But this thinking receded from the field. Thanks to the IPSS, the third version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published in 1980, was symptom focused and laid out for the first time criteria for diagnosis. This welcome standardization, however, lulled many into thinking of schizophrenia as a single disease entity, Carpenter says.

Practically speaking, psychiatrists deconstruct schizophrenia every day. Because there is no one pill to treat the disorder, they prescribe antipsychotics to calm hallucinations and benzodiazepines to deal with anxiety, or they introduce cognitive behavioral therapy to reorient a person to what is real and what isn’t. But in terms of designing studies to understand schizophrenia’s causes and find new therapies, the field has lumped all cases of schizophrenia together. This approach is akin to studying dementia without understanding that Alzheimer’s disease is different from stroke-induced dementia, says Carpenter.

The Americans’ call for deconstruction went unheard, and the field reaped what Carpenter calls “40 years of wasted science.” For decades clinical drug trials have accepted all people with a schizophrenia diagnosis, no matter their symptom profiles, and for decades these trials have failed. Drugs that initially produce promising results in small groups flounder when expanded to larger, more varied populations. Would a study based on patients with similar symptom profiles, for example, yield something clearer?

Others have picked up on these problems. Over the past decade the National Institute of Mental Health has promoted a shift to engage with component parts of mental illnesses in general, including schizophrenia. Researchers are encouraged to study a piece of an illness, such as the misreading of social cues that can lead to bizarre reactions, or deficits in working memory, which keep people from memorizing a phone number or multitasking in their job. The initiative, called Research Domain Criteria, actually recommends moving beyond symptom-based descriptions of mental illnesses to also include biological descriptions. The hope is that understanding each piece of the illness and its biology will offer more tractable goals and lead to successful therapies. From a regulation standpoint the FDA, which normally approves drugs for specific conditions, has begun to explore approvals for classes of symptoms, such as the inability to feel or pursue pleasure (anhedonia), which plagues many with mental illness.

In the years since his IPSS work Strauss has embraced a different kind of cross-cultural perspective: that between doctor and patient. This idea came from an IPSS patient who, during a follow-up visit in Washington, D.C., turned the tables and asked Strauss, “Why don’t you ever ask me what I do to help myself?”

Strauss has since tried to understand how individuals’ narratives about their lives and how they make sense of their illness may provide clues for their future. “These experiences of mental illness are real for these people,” he says. “But they don’t fit into our usual way of thinking.”