Cellophane revolutionized the packaging industry and dominated the market for decades, yet its fortunes turned with the advent of imitation plastic films. Production slowed to a near stop in the 1980s, but as cellophane turns 100 this year, it still has something to celebrate: it’s poised to make a comeback, reinventing itself as an earth-friendly polymer perfectly suited to 21st-century concerns.

Cellophane was invented in 1908 by Jacques Brandenberger, a Swiss textile engineer whose early experiments in making waterproof fabric began after he watched a spilled glass of wine stain a tablecloth. Using liquid viscose, Brandenberger created an adhesive film that proved too stiff to use on fabric but had obvious potential for more novel uses. In 1924 he sold the U.S. manufacturing rights to DuPont, where William Hale Charch reformulated the material to be completely moisture-proof. At the beginning, making cellophane was a laborious process that involved the dissolution of cellulose from objects like wood, celery, and cotton in alkali and carbon disulfide to make viscose, before returning the liquid to a cellulose state through an acid bath. It was not long, however, before machines were invented to allow mass production of cellophane, expanding its packaging use beyond a few luxury goods.

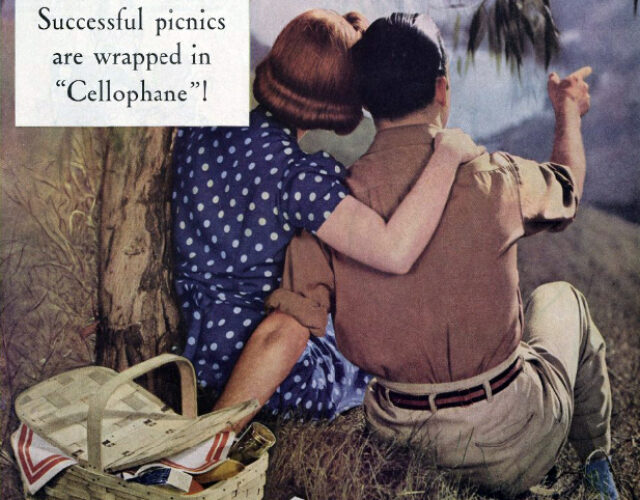

Cellophane quickly became a staple in American households. Its resistance to moisture, bacteria, and grease made it a crucial material for food packaging. It was also tapped for a variety of other everyday uses, such as cigarette packaging and Scotch-brand tape.

By the 1960s DuPont and its fellow cellophane manufacturers were selling over 440 million pounds of cellophane a year. Unfortunately, cellophane’s indispensability became its ultimate downfall, as companies sought to produce cheaper, petroleum-based versions of the product that sold under the by-then-generic name of “cellophane.” The original wood-based product’s main competitors included polyethylene for baking goods, polyvinyl chloride for meat packaging, and oriented propylene for cigarette wrappers. These materials required only half as much energy during production as cellophane. With the energy crisis in full swing, cellophane producers saw their sales plunge by the late 1970s. Cellophane’s death knell was sounded in newspapers across the country, and plants closed in large numbers.

Although a host of products referred to as cellophane have continued to flourish in the market, the genuine article has now resurfaced in response to the times. As environmental concerns increase over landfills teeming with plastic products likely to remain long past our lifetimes, cellophane stands out for its complete biodegradability, even when coated with plasticized chemicals. The natural polymer degrades within 120 days if coated, and within 30 if not. Because of this quality, cellophane is increasingly relied on to perform its old duties—and can be expected to pick up some new ones as well.

Correction: In the original text we spelled William Hale Charch’s name wrongly as Church. This version has the correct spelling.