It took some deliberation, but at last the Uzbek soothsayer and her fellow wisewomen reached a consensus: the listlessness and depression plaguing the young man before them was caused by the fairies and sprites that lived in the local rivers and tributaries, specifically the peri, who were usually benevolent. And for what crime was the boy being punished? Urinating in the flowing water that the peri called home.

This story, related by Ravšan Rahmonī, a professor of Tajik literature, comes from Central Asia, but the mindset behind the wisewomen’s verdict is not unique to that part of the world. The folklore of many cultures points toward water spirits and deities who require respect and due caution. Stories and practices centered around water hint at the similar ways different cultures have thought about fresh and running water—how it might be contaminated, how pollution might be avoided, and how to reconcile water’s necessity with its danger. These traditions were used to pass down knowledge through generations, and in some cases continue to do so. While modern society appears disconnected from the ancient world of myth, some of the knowledge hidden within these stories remains relevant today.

The Flowing River and the Stagnant Pond

Rivers are often connected to the supernatural, typically goddesses, says Joseph Nagy, a professor of Irish studies at Harvard University. Nagy stresses that an association between femininity and water is common in the mythology he studies, musing that “it’s not surprising that something as fluid and flexible and transformative as water would be associated primarily with females . . . I think it has to do with that creativity, this matrix that women are, and that water also is, for human existence.”

The result is a slew of rivers named for the divine female patrons associated with them. This is true of the Osun River in Nigeria, named after a Yoruba goddess, and the Ganges, in India and Bangladesh, which bears the name of the Hindu goddess Ganga. It’s also true for Ireland’s longest river, the Shannon, which takes its name from Sionann, granddaughter of the Irish sea god Lir, and France’s Seine, which takes its name from the Gallo-Roman goddess Sequana.

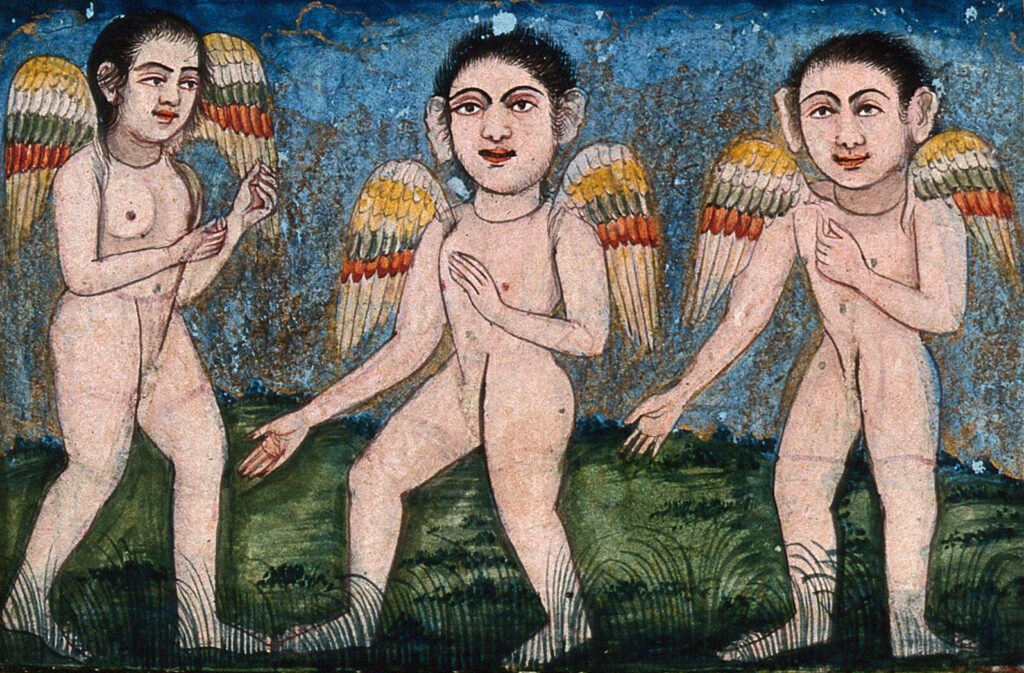

Yet lakes and ponds usually lack these divine connections. Religious practices echo this distinction between still and moving water. Harvard professor Michael Witzel notes that in Hinduism flowing rivers are seen as more divine than the still waters of the temple tanks. While rivers get associated with deities, lakes are far more likely to be associated with a resident nymph or lurking monster. This tracks with how bodies of water are used: a river is a means of travel and a source of drinking water, and thus viewed as a powerful and nurturing goddess. A lake or pond, by contrast, may be scenic or a dangerous drowning ground, or both at once. A river is powerful, a thing alive, in turns nurturing and vicious but always active; a lake or pond is far more passive. There are exceptions, certainly, from the sprites known as shellycoats that haunt Scottish rivers, to the Greek goddess Bolbe, who inhabited Lake Volvi in what is now Macedonia. But overall, folk traditions present rivers and streams as truly vital for life, while still bodies serve mostly to threaten us or, at best, offer a pretty view.

Even when a river or stream is not directly linked to a goddess, flowing water still plays a powerful role in folklore, often as a protective boundary. Historian William Halliday wrote that “the evil spirits in the forests of Burma find running water as difficult to cross as do the witches of Scotland.” In Beyond Faery, a compilation of northern English and Scottish mythological creatures, researcher John Kruse notes that crossing a watercourse ensures safety from supernatural pursuers in a vast amount of Indo-European mythology. The protective power of running water recurs in stories about vampires, ghosts, and other strange and mythical creatures.

In the early 1930s anthropologist Mary Edith Durham dug into why early cultures so venerated running water and why they thought it would stop evil spirits in their paths. Her answer? Ghosts are real.

More accurately, what people called ghosts may have been a conglomeration of real and harmful effects that could sometimes be mitigated by running water. Running water was one of the many ways early cultures attempted to protect themselves against the dead, or at least against whatever had done the killing. In her 1933 article “Whence Comes the Dread of Ghosts and Evil Spirits,” Durham wrote,

Durham suggests that modern societies feel the same way about water, in that “we insist on running water and we require that it shall be filtered and sterilized—in other words, that the ghosts shall be driven out of it.” We tend not to think of contamination as “ghosts,” but once we begin to understand the double language of folklore and tradition, such conceptualizations start to make more sense. The physically purifying properties of running water might become synonymous with the spiritually purifying properties of this water. For instance, the water that fills the mikvah, a bath used for ritual immersions in Judaism, must come directly from a flowing source.

Not all still water should be condemned. Wells, although apparently stagnant, are often the sources of rivers in Irish mythology. Take the River Shannon. Sionann, the river’s namesake, is said to have gone to Connla’s Well seeking wisdom, despite this being forbidden. In retaliation, the waters rose up and drowned her, creating a river in the process. Versions of this creation story are repeated for other Irish rivers, sometimes with lakes in the place of wells. In each example, the drowned woman comes to preside over the waterway as a goddess. The water is a deadly force, but as the woman-turned-goddess rises from the waters, water’s flip side is revealed: it is also a powerful source of life.

Myth Conceptions

Water mythology may be fascinating in its own right, but what can these stories tell us? That rivers are full of goddesses and lakes are full of monsters? Not in the 21st century. But there are practical lessons to be found within these tales, which were passed down by parents and elders hoping to convey an understanding of how nature worked and how best to interact with it.

Stories about urinating into running water are common. Folklorist David Hunt found that in the few cases in which the color yellow is mentioned in Caucasus folk literature, it likely refers to water pollution; in one story yellow is associated with giants urinating upstream and subsequently contaminating the drinking water of the story’s hero, with detrimental effects. Tales such as this one depict those who would contaminate a community’s drinking water as clearly in the wrong.

Even so, it may be difficult to read stories about divine rivers and also believe that ancient cultures had any conception of the true dangers of pollution. A look at the mythology surrounding water nymphs suggests they did.

The story of the water nymph bride usually goes as follows: a man meets a beautiful woman by a lake—a still water source, true, but one considered clean enough to drink from. He begs her to marry him and, usually after much convincing, she finally agrees; there is, however, one condition he must obey. In a Welsh version of the tale related by writer Wirt Sikes, a farmer is given the stipulation that he must never touch his bride with iron or she will leave him. Sure enough, in each tale, regardless of the stipulation, the young man agrees and lives happily with his new wife for several years before he inevitably breaks his promise. Usually, he does so by accident, but the damage is done. The beautiful woman retreats and takes her gifts with her. Or, seen from another angle, the beautiful and nourishing water, once contaminated by iron deposits or other pollutants, withdraws its blessings.

Irish mythology is littered with tales of contamination, specifically regarding the defilement of holy wells. People bathe in them, pour alcohol into them, allow their livestock to drink from or wade into them. In the process they strip the wells of their divine powers. In some cases the wells take matters in their own hands and flee this desecration, as in a story about St. Mell’s well, as recorded in Ireland’s National Folklore Collection, in which a butcher drives the well away by repeatedly cleaning animal parts in it.

In the 21st century, such traditional stories and practices based on water have not kept up with environmental changes. Witzel writes that “local folklore about the Ganges’ cleanliness persists: the river purportedly ‘cleans itself’ in spite of all its garbage, sewage, and half-cremated dead bodies. In fact, people not only bathe in the river, they also collect it to carry home over long distances; some habitually drink it. Such is the power of myth.” Similar phenomena occur in Western societies, as with Christian baptisms performed in Appalachian rivers polluted by mining.

Yet some folk traditions about the power of water still manage to prove their relevance, sometimes in dramatic ways. Take, for example, the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami and the havoc it wreaked from southern India to Africa.

Anthropologist Frank Korom describes a proverb from the Andaman Islands, located in the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, that says, “when the water goes out, run up.” The proverb relays a phenomenon known as drawback, in which water is initially pulled from shore as a tsunami approaches. Fast-moving floodwaters soon follow, but the warning can allow the observant to flee to safety.

Indeed, though nearly 230,000 people died in the 2004 tsunami, an entire Great Andamanese tribe survived by seeking higher ground the moment they saw the tide begin to retreat, taking refuge in the forest until help could arrive. Far from moot, the knowledge passed down through folklore and proverb had succeeded in doing what had always been such stories’ loftiest goal: it showed people how to survive in a dangerous world filled with gods and monsters.