Sewer smell calls to mind parts of a city we would rather ignore. It’s incongruous with something as picturesque as the Salto del Tequendama. Yet the scent is unmistakable as the cascades spill from the lush Andean forest. This 132-meter-tall waterfall is emblematic of the high plain of Bogotá. Indigenous Muisca people believe their god Bochica broke open the falls to drain the plateau after a great flood imperiled their ancestors. These days Tequendama’s waters course toward a treatment plant, built to filter the reeking pollution that travels 20 miles downstream from Bogotá.

The treatment plant sits near a rocky outcrop that has stood for millions of years, long before any human set eyes on the falls or the falls existed at all. The rocks have seen the high plain of Bogotá morph from sweet-smelling forest to stinking swamp. They have sat at the bottom of an enormous lake so deep it could submerge most of Bogotá’s buildings.

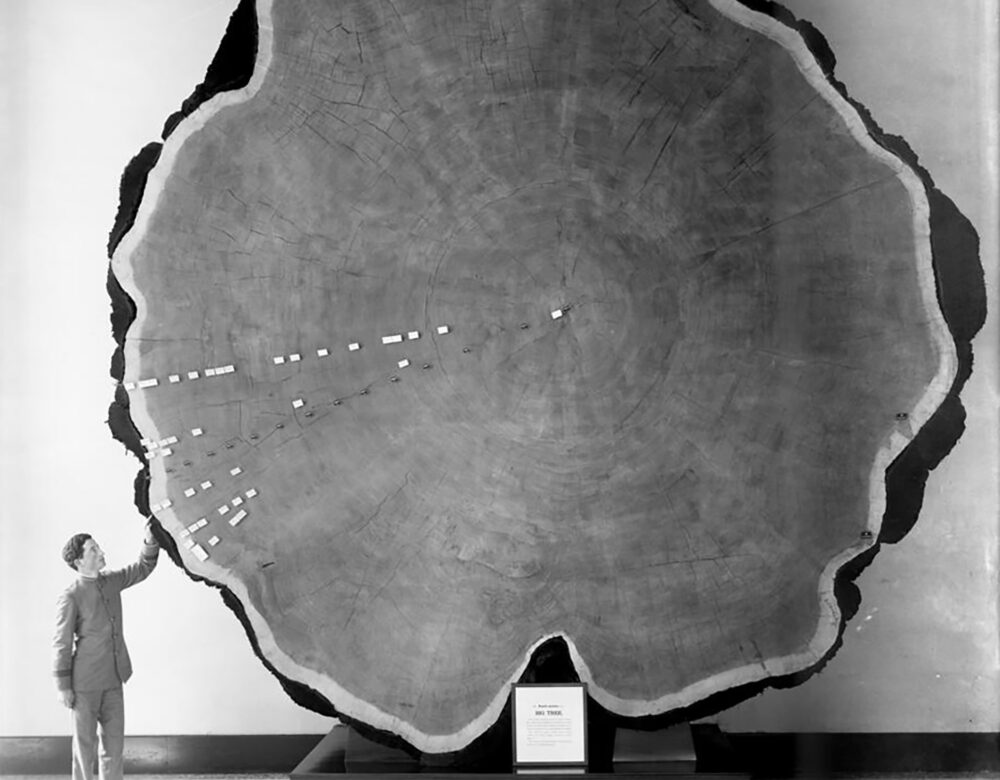

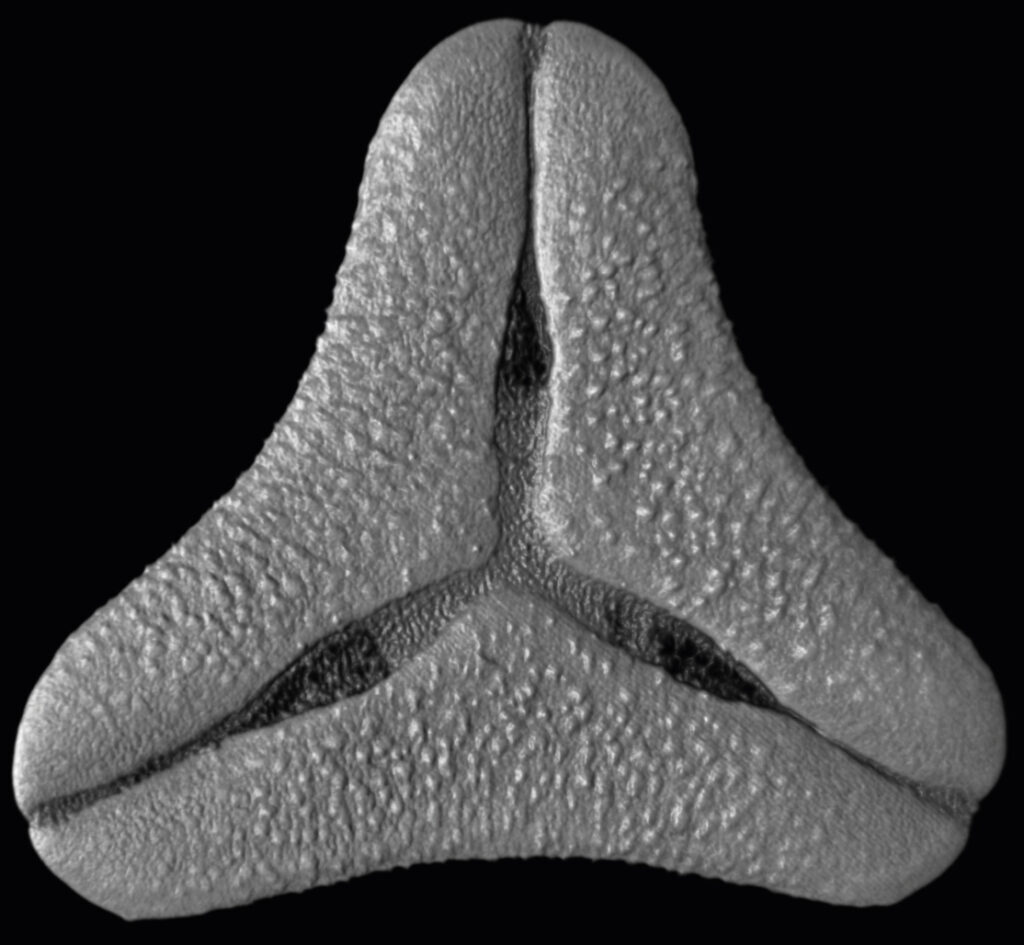

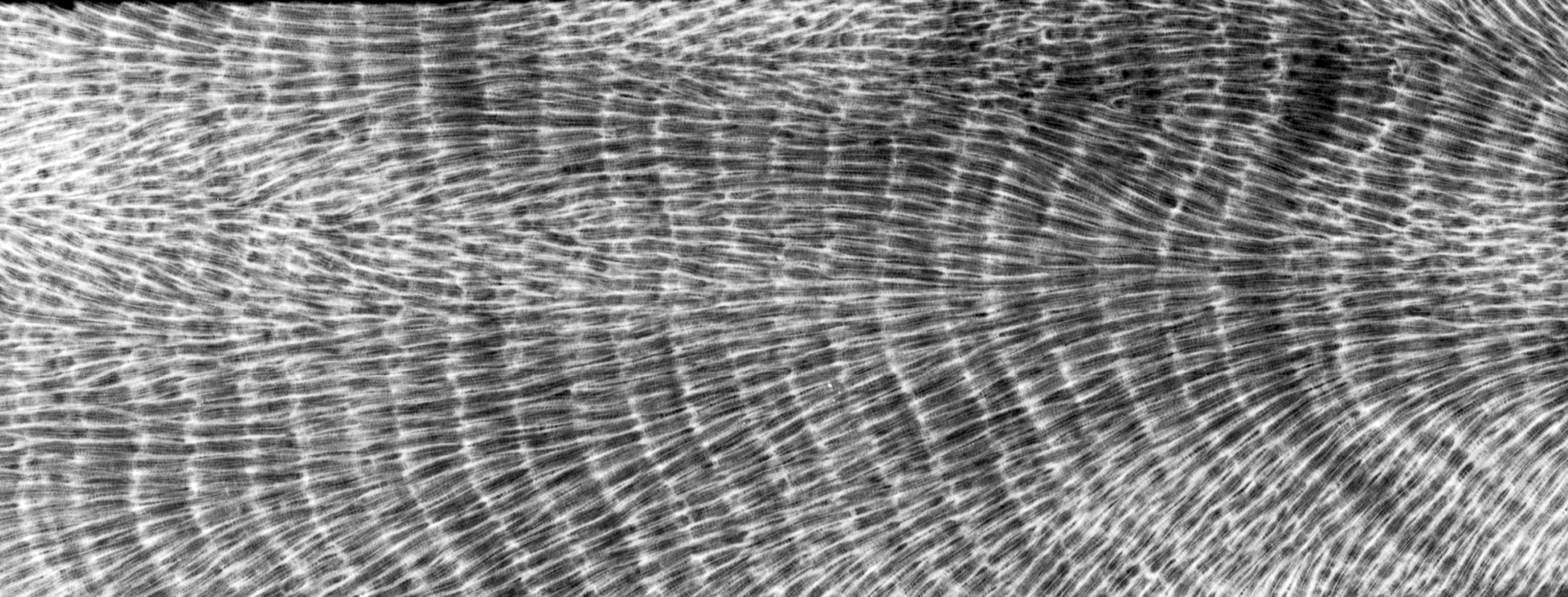

We know this because these rocks are not just witnesses to the region’s environmental changes—they record them. Climate scientists call them archives, enduring natural features whose physical and chemical characteristics are steadily shaped by their surroundings. Other common climate archives include corals, ice cores, lake sediments, and tree rings. Geochemical, physical, geological, and biological measurements obtained from these archives are called proxies. Scientists can read proxies like detectives read a crime scene, collecting clues in the climate archives that help decipher changes in environments and plant communities from the intangible past.

The relative ubiquity of archives such as the outcropping at the Salto del Tequendama may lead one to believe access to the deep past is available to scientists around the world, but that’s not the case.

Scientific papers and literature guide the journey to these bygone territories. However, most of this discourse comes from Europe, the United States, and other mid-to-high-latitude regions, not tropical ones like Colombia. Likewise, the universities that house the bulk of the samples from these archives are located in colder climates—places where it is hard to imagine the tropical forests that once stood or how they smelled. But this experience-based imagination matters. It helps us understand how ecosystems changed before the arrival of humans and helps us grasp how resilient they have been over millions of years.

Societal disparities have made some regions better known than others. The geological past of the Salto del Tequendama, for example, is lesser known outside of Colombia than other climate archives. Inequalities in climate science, such as language barriers and the uneven geography of knowledge production, hinder our understanding of climate in tropical regions and the southern hemisphere. For climatologists in the tropics, these inequalities exacerbate problems that hamstring all climate science—poor data standards across regions and disciplines, lack of access to reproducible open data, and even the lack of collaboration and data sharing across disciplines. And that’s only part of the story; some archives themselves embody climate injustices. Consider tree rings.