By Thanksgiving 1917, U.S. troops were just entering the battlefields of the Western Front, but by then World War I had long since crossed the Atlantic. For years the United States, though officially neutral, had bolstered Allied forces with munitions and other supplies.

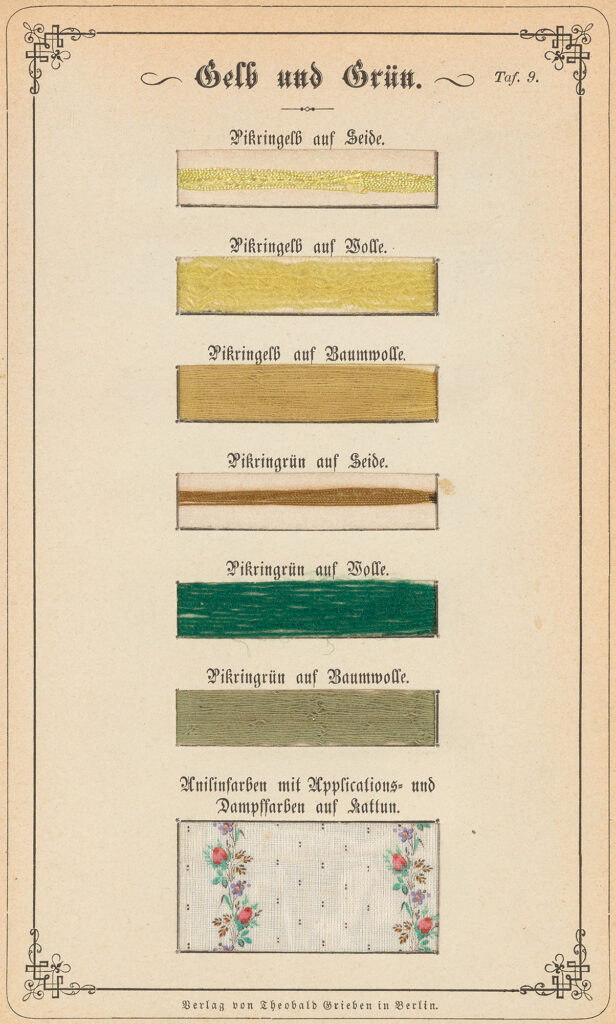

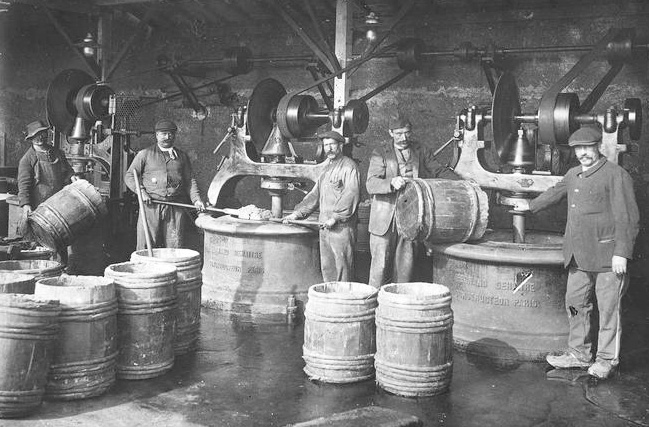

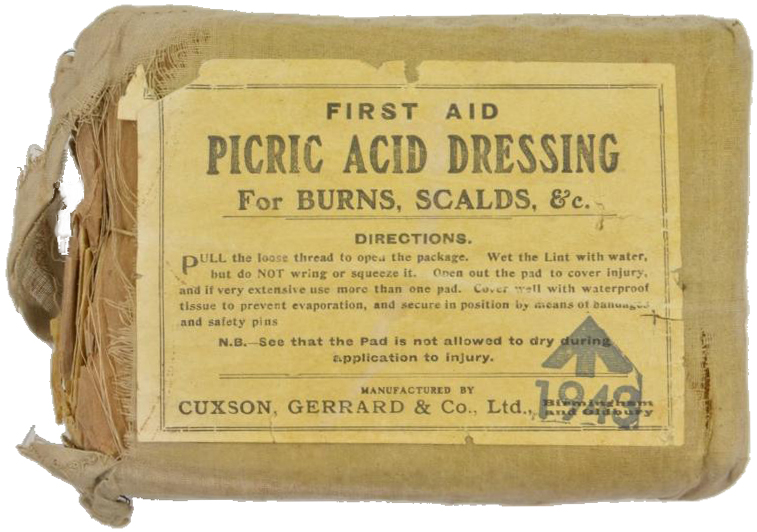

On the chilly banks of New York Harbor the SS Mont-Blanc, a French ammunition ship, was packed with an explosive cargo of 62 tons of guncotton, 250 tons of TNT, and—most dangerous of all—2,366 tons of picric acid. Just before departing, a last-minute order from France tacked on a load of benzol, a highly volatile gasoline substitute. In haste the stevedores jammed the barrels onto the ship’s deck. Without realizing, they had created the perfect fuse.

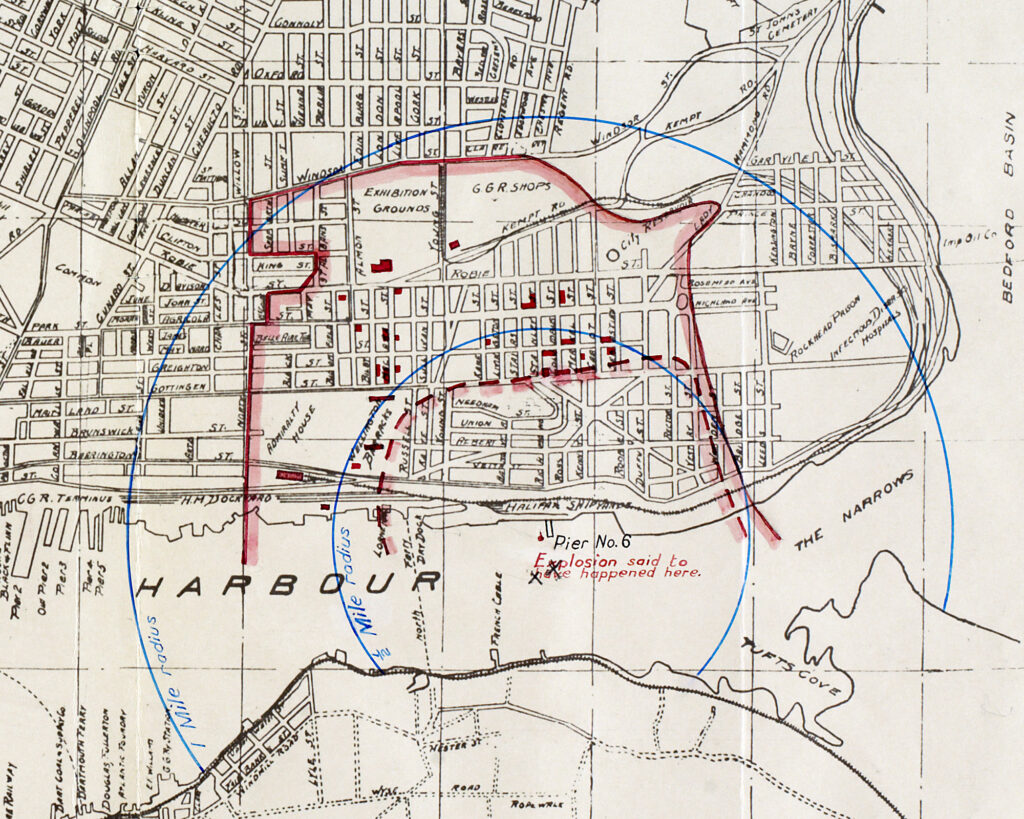

The crew set sail, cruising north toward Halifax Harbour in Nova Scotia and an Allied convoy preparing to cross the Atlantic. In safer times, they would have flown red flags warning of their cargo, but the threat of German U-boats had suspended this practice. The Mont-Blanc crept up the coast through stormy weather, reaching Halifax on December 5. Arriving too late to enter the harbor, the crew threw anchor and waited anxiously for dawn.

The next morning, after anti-submarine nets had been raised, a pilot guided the ship into the harbor, navigating cautiously toward the tight strip known as the Narrows. There the crew caught sight of the Imo, a relief ship bound for Belgium, steaming hard toward them—infringing on Mont-Blanc’s lane. The pilot sounded warning blasts, but the Imo blasted back in response, refusing to budge. At the last moment, the ships’ pilots maneuvered to avoid a collision, but it was too late.