Chris Marshall was a 22-year-old auto mechanic in Northeast Philadelphia when he first took Percocet, a prescription painkiller. Percocet is a combination of acetaminophen, the main ingredient in Tylenol, and oxycodone, an opium derivative. His grandmother gave him a pill when he hurt his back at work and then gave him 10 more in case he got hurt again. “My grandmother, bless her heart, she had no idea what she was doing,” he said. “She was trying to help.”

A couple of months later he hurt his back again, even worse this time. “I never felt pain like this,” he recalled. “Something said to me, ‘You know what? One’s not going to be enough.’ I took two of them, and I was like, ‘Whoa, what is this?’ I felt something I never felt in my life. Something clicked in my brain at that moment that said, ‘This is the way you were supposed to feel your whole life and never did.’ After I came down off two, I’m like, ‘If two felt that good, I wonder what three feels like?’ And then, boom, I was off to the races.”

Scenes from the Kensington neighborhood, a part of Philadelphia known as the Badlands and the epicenter of the city’s current opioid crisis and the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s.

A few years later Marshall had back surgery for his injuries, and his doctors were happy to prescribe him whatever pain drugs he asked for, including OxyContin, a widely used slow-release form of oxycodone. When he ran out of pills, he found he could buy them from dealers on the street. He soon realized he had developed a habit and entered a weeklong detox program, where he heard endlessly about heroin, a drug he had never tried. During the drive home a woman who had been in the program asked if he really had never used it. “Would you want to?” she asked. Having been primed all week, he had no doubts: “Hell, yeah, I want to try it!” He injected his first bag of heroin that day and from there his life went “all downhill.”

Marshall would go on to abuse methadone, an opioid used to treat people with addictions, and combined that drug with Xanax, a benzodiazepine tranquilizer. He injected cocaine and smoked crack cocaine. He sought out fentanyl, an extremely potent, fast-acting synthetic opioid. He stole from his mother and his son to pay for drugs, was estranged from his family, and became homeless. He lived under a bridge at the site of a notorious open-air drug market in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, shooting dope and watching other users destroy themselves. “I was just waiting for that one bag that would kill me,” he said, “or somebody being sicker than me and stabbing me and taking my stuff away.”

A Historic Catastrophe

To anyone who has followed the nation’s staggering opioid epidemic, Marshall’s story is familiar, even unremarkable, despite its horrors. Since Purdue Pharma released OxyContin in 1996—reintroducing the public to opioid use for routine pain relief for the first time in a century—abuse of the pills and similar drugs has exploded. People are prescribed the pills, get them from a friend, or find a family member’s leftovers. They become dependent and need more to get high and stave off withdrawal sickness. When their money runs low, they switch to heroin, a cheaper, faster-acting alternative, often snorting the powder first and later taking up the needle. As demand spreads, dealers appear in more communities, and the stigma of using heroin fades. More and more users are having their first opioid experience with illegal substances rather than prescribed medicines.

Part of the tragedy is that the epidemic should not have been a surprise. Humans have suffered mass addictions to opium derivatives for hundreds of years, and every time chemists tried to formulate safer versions, they instead produced stronger and deadlier drugs. Along the way opioid producers have repeatedly cashed in on the substances’ irresistible pull, amassing fortunes. Even after societies came to understand the danger and restricted the drugs, Purdue and other companies were able to exploit demand for better analgesics and sell their highly addictive new versions as somehow safer than the old ones. They turned doctors into the Johnny Appleseeds of a renewed opioid crisis, leaving communities to mourn the resulting devastation and governments scrambling to end the plague, so far with limited success.

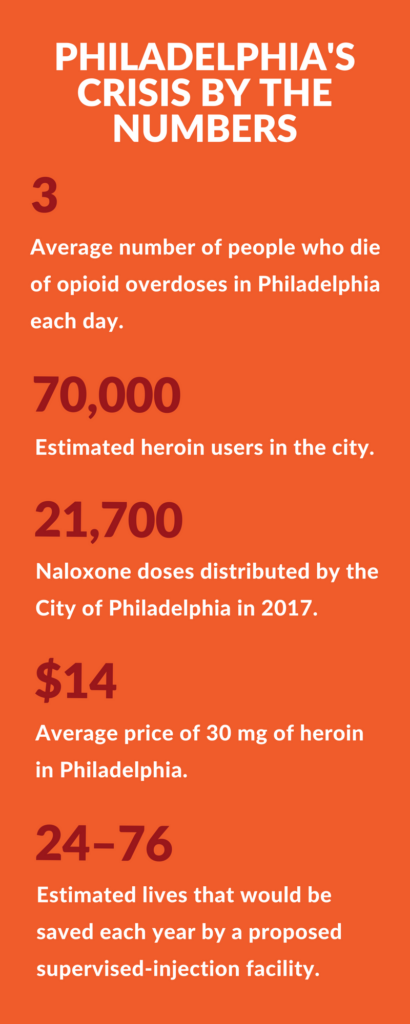

Overdose deaths have climbed steadily since OxyContin hit the market, with deaths from opioids specifically beginning to spike around 2013 due in part to a jump in fentanyl use. In 2000, 17,415 Americans died of drug overdoses, 8,407 of them from heroin and other opioids. In 2016 there were at least 63,632 deaths, of which 42,249 involved opioids; that’s more than 800 people a week. Overdoses are killing more people than have ever died annually from car crashes, HIV, or gunshots. Overdose deaths contributed to a 2½-month reduction in average U.S. life expectancy from 2014 to 2016, the first time projected longevity has fallen for two years in a row since the early 1960s.

And those figures only count deaths, not the hundreds of thousands of overdoses users survive. More than 2 million Americans have opioid abuse disorders; around 600,000 are addicted to heroin.

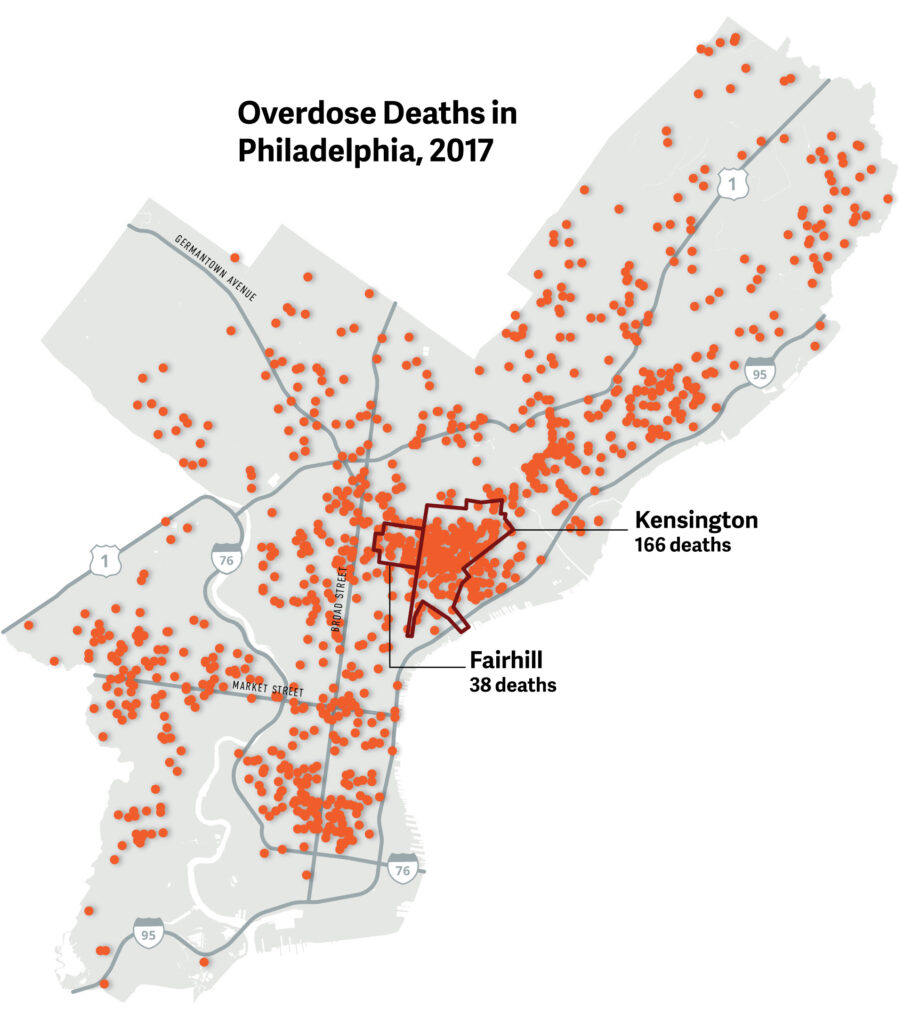

So far, however, health advocates are losing the battle. The number of opioid prescriptions has declined from its peak but is still far too high, and deaths from all opioids continue to climb sharply. Fentanyl and fentanyl-laced heroin have flooded illegal drug markets, killing thousands of users. In Philadelphia, overdose deaths jumped by a third from 907 in 2016 to 1,217 in 2017. Eighty-eight percent of last year’s deaths involved opioids, compared with 80% in 2016.

“Fentanyl has taken over from heroin as the number one drug that’s killing people in Philadelphia today,” Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said in April. “It is a particularly potent, particularly addictive, and particularly deadly opioid, and that has thrown gasoline on the fire of the crisis we were already seeing.”

Young people from around the Philadelphia region and the country have been streaming into the city, driven by their addictions to find the most powerful drugs. Marshall said he met a man who spent four months hopping boxcars from California to Philadelphia so he could score one last fix of strong, cheap heroin before entering a recovery shelter. The health department hired an additional medical examiner to process all the bodies. The local epidemic attracted national attention in May 2017 after a Philadelphia Inquirer columnist wrote about a public library in Kensington where staff members carry naloxone. The librarians were regularly reviving overdose victims who collapsed in the bathroom or on the needle-strewn front lawn.

An Elusive Grail

Those seeking to stem the epidemic have a tough adversary: a tenacious chemical affinity between the poppy plant and the human brain that dates back thousands of years. Opioids are uniquely effective pain relievers, don’t directly harm the body’s organs, and give users the euphoria and sense of well-being Chris Marshall and countless others have felt.

There were 1,217 unintentional drug-overdose deaths in Philadelphia in 2017, an increase from 907 deaths in 2016. Opioids were involved in 88% of these deaths, with most of those involving the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl. In the Kensington and Fairhill neighborhoods alone—the former site of a large open-air drug market and homeless encampment—at least 204 people died from overdoses.

When chemists tried to understand and improve on opium, they ended up making morphine and heroin; both were developed as medicines and initially marketed as non–habit forming, or even as treatments for addiction, only to be revealed as actually more addictive than earlier formulations. That’s because opioids fit into the body’s reward system like a key in a lock. In healthy people natural endorphins—“endogenous morphine” chemicals—are released in response to stress, injury, exercise, and sexual activity. They attach to µ-opioid receptors and other receptor molecules in the brain and gut, sparking chemical cascades that block pain and produce pleasurable feelings. These endorphins include minute amounts of naturally produced morphine.

When people take heroin and other opioids, the drugs attach to the endorphin receptors more strongly and persistently than the body’s natural endorphins, leading to more intense euphoria and pain relief. The drugs also cause a release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that signals a pleasurable experience is coming and reinforces desire for it to happen again. That release soon creates a focused craving for more of the drug. The main harmful effect of opioids is weakened breathing, which becomes dangerous at high doses.

Opium’s potency suggests that humans bred the poppy plant over millennia, selecting and cultivating the strongest strains. The ancient Sumerians, who lived in what is now Iraq, recorded using a substance thought to be opium medicinally and recreationally around 3300 BCE, and from there it spread through the Middle East to Greece, where Hippocrates prescribed it to insomniacs, and then on to India and China. In the 17th century Portuguese sea merchants profited handsomely from exporting opium to China. The British later took over the trade, and by the early 19th century China found itself with millions of people addicted to smoking the drug. When the Chinese regime tried to block imports, Britain launched two wars to maintain and expand its massively lucrative drug traffic. Opium also became ubiquitous in England and the United States in the form of patent medicines and drinks, which workers consumed to ease the miseries of poverty and parents used to quiet their children. In the late 19th century opium addiction became a quiet plague among middle- and upper-class American women.

Part of the tragedy is that the epidemic should not have been a surprise. Humans have suffered mass addictions to opium derivatives for hundreds of years, and every time chemists tried to formulate safer versions, they instead produced stronger and deadlier drugs.

Opium had important medical uses during the centuries when doctors had few good treatments for many ills. It extinguished pain, helped people sleep, and treated potentially fatal diarrhea. Scientists were eager to identify and separate out an “essence” of opium that would provide these benefits without the addictive effect. German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner experimented with poppy-seed juice and in 1804 isolated a sleep-inducing substance he named after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams. Morphine was the first alkaloid compound ever identified, leading the way to the discovery of others, including strychnine, caffeine, and nicotine, in the succeeding years. Later researchers isolated opium’s other alkaloids, including codeine and thebaine, the substance from which oxycodone and the addiction-treatment drugs naloxone and Suboxone are made.

Sertürner tested morphine on himself and knew it was far from harmless; he experienced euphoria, depression, nausea, and, some historians believe, addiction. Nonetheless, the chemical was hailed as a wondrous painkiller. In the 1850s the perfection of the hypodermic syringe encouraged use of the drug, writes Martin Booth in Opium: A History. Physicians assumed that “injection, as opposed to ingestion, would not lead to an appetite for the drug. . . . Remove the act of swallowing, they reasoned, and hunger would be assuaged.” They were wrong, of course. The speedy adoption of morphine injections as both medical treatment and leisure activity, especially among upper-class families who could afford syringes, made dependency common. Opium pills and morphine shots became staples in army field hospitals during the Civil War, and soldiers brought their “morphinism” home with them. In 1867 Harper’s Magazine lamented the opium habit was “gaining fearful ground” among “all our classes from the highest to the lowest.”

A nonaddictive opium derivative became a holy grail for researchers. English scientist C. R. Alder Wright developed hundreds of new opiate compounds, some of them through a process called acetylation; notably, in 1875 he boiled morphine with acetic anhydride to create diamorphine. Initially diamorphine received little attention, but it resurfaced at Bayer Laboratories in Germany more than 20 years later. Chemist Heinrich Dreser asked his researchers to investigate acetylation, and over a period of two weeks they synthesized two of history’s most significant drugs. Dreser initially rejected the first, called acetylated salicylic acid, or aspirin, saying it would harm the heart. The other was Wright’s diamorphine, which Dreser tested on his workers and dubbed “heroin” for the supposedly heroic feeling it created.

Heroin was cheap, easy to make, fast acting, and powerful in small doses; Bayer touted it as a cough medicine that could safely treat asthma, bronchitis, and tuberculosis. Sales of heroin in powdered, capsule, and liquid forms took off. Dreser thought the alteration of morphine’s molecular structure made the drug nonaddictive, but he too was wrong. As for aspirin, one of Dreser’s researchers had gone around him to arrange testing of the substance, which proved relatively safe and became hugely successful. Bayer’s website proudly describes aspirin as the “drug of the century” but makes no mention of the company’s other, equally consequential product.

A Deadly Fraud

Chemists continued to seek the magical formulation that would suppress pain without causing dependency, and they continued to fail. In 1916 University of Frankfurt researchers developed oxycodone, apparently hoping a thebaine-derived drug would not be habit forming. In the 1930s German scientists came up with Demerol and methadone, which are fully synthetic opioids manufactured from various chemicals rather than from the poppy plant. In 1959 the Belgian physician Paul Janssen created fentanyl, another synthetic drug, which is 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin.

Heroin’s addictiveness had become clear soon after its introduction, alarming doctors and health advocates and leading to international restrictions on production of the drug. The United States clamped down on opioid distribution in 1914 and outlawed heroin in 1924. Doctors, fearing prosecution, learned to see opioids as dangerous substances to be given only to dying patients, if at all. The stigma against opioids lasted through most of the 20th century, doubtless saving many lives but leaving patients who had chronic pain to suffer. In the early 1970s awareness of the danger of dependency was reinforced by a scare over addictions American soldiers developed during the Vietnam War. A study of returning troops found that 43% had tried narcotics, primarily heroin. Nearly 20% of the soldiers surveyed had become addicted, though it turned out most quit using heroin after leaving behind the stresses and triggers of wartime service.

The renormalizing of opioid use began in the late 1960s with experiments at a hospice in England where terminally ill patients were prescribed large amounts of painkillers and even heroin. In the 1980s the World Health Organization, galvanized by the agonies of dying cancer patients in poor nations, published a system for evaluating levels of pain and prescribing the appropriate drugs. As journalist Sam Quinones recounts in Dreamland, a history of the current opioid crisis, consumption of morphine began to climb as a new philosophy of pain management took hold in the United States.

The movement was led by two physicians at New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Kathleen Foley and Russell Portenoy. Foley began as an advocate for better pain management in cancer patients, but she came to believe opioids shouldn’t be reserved for the terminally ill and severely injured; they should also be used for “pain that was chronic but equally life mangling—bad lower backs, knee pain, and others,” Quinones writes. In 1984 Purdue helped this trend along by introducing MS Contin, a timed-release morphine pill.

Foley and Portenoy spread the gospel of proactive pain management widely. “We had to destigmatize these drugs,” Portenoy later told the Wall Street Journal. Advocates argued, without any evidence, that people who suffer chronic pain are resistant to addiction. “You can’t get addicted to opiates because the pain soaks up the euphoria,” as one physician described the theory to Quinones. Proponents frequently cited a 1980 study showing less than 1% of patients treated with narcotics developed addictions. In reality, the supposed “landmark study,” by medical researcher Hershel Jick of Boston University, was a one-paragraph letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. It reported that of nearly 12,000 patients treated with opioids while hospitalized, Jick’s database recorded only four who had become addicted. Jick later expressed amazement that his brief report, which had nothing to do with taking pills at home for chronic pain, was so widely mischaracterized to encourage use of powerfully addictive drugs.

“Addiction is really a struggle between your frontal lobe and the nucleus accumbens. . . . There’s this struggle between the good and evil in your brain.”

By the time OxyContin was released in 1996, the revolution in opioid prescribing was well under way. The American Pain Society, a drugmaker-funded group founded in 1977, said chronic pain was underdiagnosed and promoted the notion of “pain as the fifth vital sign” doctors should monitor, like body temperature and pulse. Purdue executives argued patients could take just one OxyContin pill every 12 hours, providing a steady dose that created fewer surges of euphoria and depression and made the new formulation less addictive. In truth that theory was baseless, and they ignored evidence that OxyContin was still addictive, but the FDA allowed them to make the claim despite the lack of supporting evidence.

A generation earlier Purdue owner Arthur Sackler had ignored concerns about the addictiveness of the anti-anxiety drug Valium and used aggressive marketing to make it the first billion-dollar medicine. Now his successors sent out an army of salespeople and marketers in the service of another dangerous drug. They besieged doctors’ offices with free samples and gifts, bearing fraudulent charts and studies showing OxyContin’s supposed safety. “The company advertised in medical journals, sponsored Web sites about chronic pain, and distributed a dizzying variety of OxyContin swag: fishing hats, plush toys, luggage tags,” Patrick Radden Keefe writes in the New Yorker. “Purdue also produced promotional videos featuring satisfied patients—like a construction worker who talked about how OxyContin had eased his chronic back pain, allowing him to return to work. The videos, which also included testimonials from pain specialists, were sent to tens of thousands of doctors.” Patients learned about the drug and demanded the pain relief they believed was their right. When they inevitably developed a tolerance and needed higher-dose pills, their doctors obliged them, believing the drug safe. Patients were supposed to be screened for risk of addiction, but this precaution was rarely taken.

The marketing campaign surely led to relief for some pain sufferers but soon proved devastating in a number of states, particularly in the Midwest. Quinones describes the early days of the epidemic in southern Ohio, which by 1998 was awash in OxyContin addicts. “Patients would go to doctor after doctor with stories of pain and requests for more of the new drug,” he writes. “Dealers who sold meth or cocaine on the street started pushing Oxy. Addicts learned to crush it and snort it, or inject it, obtaining all twelve hours’ worth of oxycodone at once.” Senior citizens sold their extra drugs to kids. Unscrupulous doctors opened pill mills, dispensing hundreds of unnecessary prescriptions a day to people with addictions. Abuse of OxyContin spread across the country, as did overdoses and deaths.

A rise in heroin fatalities soon followed. The drug had gone through vogues before, as part of the Harlem jazz scene of the 1930s and 1940s, among 1950s Beatniks, and with Vietnam War soldiers, but the death count had always been relatively low. That began to change in the 1980s and 1990s as the product became cheaper and purer. Quinones describes a new breed of dealers who sold high-quality black-tar heroin, a previously rare form of the drug, using decentralized trafficking networks. Impoverished Mexican farm kids were heading north across the border to make their fortune in the delivery business, driving around Los Angeles or Seattle or Columbus, Ohio, with $5 balloons of heroin in their mouths. If they encountered the police, they quickly swallowed the balloons. Their bosses focused on quality, cost, and convenience, servicing a growing pool of users ready to transition from more expensive and slower-acting opioid pills.

The Mexican dealers tended to stay out of traditional East Coast heroin hot spots, such as New York and Philadelphia. Trade there had long been dominated by violence-prone gangs that distributed powder heroin from Asia, the Middle East, and Colombia. The powder was expensive and usually cut with baking soda and other adulterants. But as the market for the drug expanded rapidly in the early 2000s, powder purity increased and prices plummeted, even in the Northeast, aided by the proximity to Interstate 95.

“The Best Feeling in My Life”

Jick’s letter to the editor was badly misused, but the data wasn’t wrong. Studies have found that among people who are prescribed opioids, even for outpatient use, addiction rates are very low. Anyone who takes opioids repeatedly will become dependent and experience withdrawal symptoms, but only a small subset of people will develop substance abuse disorders with compulsive drug-seeking and harmful consequences. Those in the latter group are the real victims of the careless marketing of opioids. “The calamity is that a broad regulatory and cultural shift released a massive quantity of addictive drugs into the public at large,” wrote Christopher Caldwell, an editor at the conservative magazine Weekly Standard. “Once widely available, the supply ‘found’ people susceptible to addiction.”

Chris Marshall isn’t exactly sure why he’s one of the vulnerable, but he has a theory. It’s not because he was deprived or abused; he says he grew up in a “great family.”

“I was a pretty good kid,” he said, “but a short, fat kid in class. I had glasses, used to get picked on a lot, you know what I mean? But I still put a lot of love out in the world. When I put that first bag of heroin in my arm, it felt like all the love I ever put out into the world came back to me all at once and gave me a hug. It was so overwhelming; it was a spiritual experience.” He felt like a better parent and son, and life looked “a little more colorful.”

“That hole in my soul that I’ve been looking to fill for my whole life with love or whatever it was, was filled by this drug,” he said. “I felt complete. I felt I had arrived.”

Chris Marshall, photographed in April 2018.

For others the likely impact of their early experiences is clearer. Barry Salop, a 51-year-old professional chef who lives near Philadelphia, calls his addiction an “allergy” he was born with, but he also describes a profoundly traumatic childhood. His mother was married five times and his father four times; their partners had addictions to gambling, sex, drugs, or alcohol, and there was mental illness as well, he says. He was sexually abused by multiple stepparents. A stepsister died young; his mother went to federal prison for dealing drugs; he suffered from painful, chronic ear problems. He smoked marijuana at 8 years old and used cocaine at 11.

“My earliest memories as a kid are just feeling uncomfortable in my own skin, fearful of everything,” Salop said. “I was introduced to drugs at a very young age, and I used drugs as a coping mechanism.” Opioids entered the picture when he was 18; he had excruciating ear pain one day, and an acquaintance gave him a pill. “It was the best feeling in my life,” he said. He mostly stuck to cocaine until around 1996, when he was given oxycodone for a medical problem and felt the old bliss again. He eventually switched to powder heroin to save money, though he says a fear of needles kept him from ever shooting up. “It sounds sick, but opiates were my love. Alcohol had never done it for me. Stimulants did it, but they weren’t helpful with anxiety and fear. I discovered that opiates were the high for me,” he said. He relied on opioids to get through his day—to make a phone call, to work, to get out of bed. Oxycodone, hydrocodone, heroin, fentanyl, even Suboxone in a pinch to prevent withdrawal symptoms.

Both nature and nurture contribute to addiction. The exact genetic mechanisms are unclear, but the environmental issues that increase risk are well understood. A child who experienced abuse, parental conflict, seeing a family member killed, or some other terrible event is more likely to try an addictive substance and more likely to get hooked. Dopamine is involved in managing environmental stresses, and in young people with more plastic, changeable brains, high stress rewires the dopamine pathways. That can result in reduced emotional and behavioral control, motivating them to self-medicate, making them more impulsive, and ruining their decision-making abilities.

The self-destructive pattern is aggravated by opioids. Drug-induced surges of dopamine in the brain and a welter of other chemical processes damage the prefrontal cortex, where rational thinking occurs, and overload the nucleus accumbens, the region where dopamine release causes pleasurable feelings. Absence of the drug triggers craving and a fierce focus on finding more. Without the prefrontal cortex’s moderating influence these cravings lead to aberrantly pathological and criminal behavior that users’ friends and families find bewildering. “Addiction is really a struggle between your frontal lobe and the nucleus accumbens,” said Joseph D’Orazio, a medical toxicologist at Temple University and a participant in Philadelphia’s opioids task force. “Your frontal lobe is telling you, ‘this isn’t good for me, this isn’t the right thing to do, I shouldn’t be using heroin,’ but then the nucleus accumbens is the part of the brain that controls the rewards. There’s this struggle between the good and evil in your brain.”

“Logic, sense, and reason go down the toilet,” Marshall said. “The drug becomes a part of you and you’re used to it. It becomes more important than food. If you could choose the drugs over oxygen, you would probably choose the drugs, if you had that choice. As the user keeps using, they lose things. They give things away, whether it’s relationships with family, their possessions, or their money, and they go further down that spiral.”

In the depths of his addiction Marshall was approached by a man who gave him a bag of heroin and made him an offer: go into stores, use fake identities to open credit accounts, and make purchases with no intention of later paying the bill. In return Marshall would receive money and drugs. He eventually got caught, spent a month in jail, and entered a drug rehabilitation program. When he relapsed and failed a drug test, he was ordered to serve his full term. During the two weeks before he returned to jail, two friends gave him a tough talking-to, telling him he needed to start acting less selfishly. Something clicked, finally. He knew he could get drugs in prison if he wanted them, but he managed to stay sober. When he got out in 2012, he moved into a bare-bones shelter in Kensington called the Last Stop, where he spent the next five years helping others stay clean and rebuild their lives.

An arrest turned things around for Salop, too, after years of misery. His tolerance to opioids had gotten so high he was constantly battling withdrawal sickness and barely feeling any pleasure. “The doses I was taking would kill someone,” he said. His life revolved around drugs. He would blow up at people, lose jobs, have moments of clarity, detox with Suboxone, dabble in 12-step recovery programs, visit therapists, and inevitably return to using. He bought a house, lost it, and went bankrupt. Addicted to alcohol and opioids, he was living with his partner and her three children and growing marijuana in the garage, until the day more than a dozen police officers raided the home and charged him with multiple felonies.

Salop went into treatment, first at a center in Pennsylvania and then a facility in Minnesota, followed by a year in a sober-living house. His family supported him and participated in therapy. He threw himself into 12-step philosophy, learning to view his addiction as a disease he cannot control and putting his faith in a higher power to take care of him. “For the last three and a half years I start my day the same way every day, with prayer and meditation, and then spiritual reading. I’m pretty much guaranteed to have a daily reprieve that’s based on the maintenance of my spiritual condition,” he said, echoing a central concept from 12-step programs.

He doesn’t blame his childhood or the drugs for his troubles. He knows people who have needed prescribed opioids for pain and were able to taper off them successfully. Those people don’t have “this thing,” he said, the craving that made him chase drugs and alcohol for so many years. He now works as a chef and manager at a recovery house and gives talks at hospitals about his experience. As his recovery took hold, the prosecutors reduced his charges to misdemeanors, allowing him to avoid jail.

In 2017 Philadelphia cleared and fenced off railroad tracks that for years had hosted an open-air drug market and homeless encampment. Soon camps cropped up in vacant lots and under overpasses in the surrounding Kensington neighborhood. In spring 2018 the city began clearing these camps, a move some advocates fear will disrupt health services and lead to more deaths.

Science Struggles for a Solution

Drugs that target opioid receptors are essential to managing pain, so work continues on finding less-addictive versions, despite the sorry history of such efforts. An area of research that recently stoked excitement involves β-arrestin, a protein produced by the body that attaches to opioid receptors when a person takes morphine. Arrestins seem to contribute to dependency, suppression of breathing, and tolerance. Scientists identified a morphine alternative called oliceridine that does not engage the β-arrestin pathway as strongly and tested it on people getting tummy tucks or having bunions removed.

Oliceridine provided some pain relief but affected breathing much as morphine does, dampening enthusiasm for the drug. Even if the results were better, they would not necessarily mean the substance is safe for long-term use for chronic pain. Its addictiveness in people is unknown, but in a mouse study it caused typical “abuse-related effects.” Other opioid-related drugs, including a class of painkillers called κ-opioid agonists, have also been tested with mixed results. For now the holy grail of the non-habit-forming opioid remains a dream. “When I see it, I’ll believe it,” said D’Orazio, who spends his days tending to emergency-department patients ravaged by addiction. “I can’t imagine there’s such a thing.”

Researchers have experimented with targeted therapies, such as viruses that carry endorphin-producing genes into the spinal column, but have so far failed to develop an effective drug. Among nonopioid approaches, painkilling substances called sodium channel blockers have shown promise and are advancing through clinical trials. In the meantime helpful nondrug alternatives include physical therapy, exercise, acupuncture, meditation, yoga, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. These can reduce and sometimes even end pain, unlike opioids, which lose effectiveness over time and don’t address underlying health problems. Unfortunately, although these therapies cost less in the long run, insurance companies often refuse to pay for them, considering them unproven. Suffering patients may also prefer taking pills for quick and easy relief rather than spending weeks limping to physical therapy. In a hopeful sign, the epidemic has prompted insurers and Medicaid programs in some states to take nondrug methods more seriously.

Work also continues on new ways to help people who are already hooked. In a report on science’s role in addressing the crisis, the heads of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) celebrate the development of Narcan, a nasal-spray form of naloxone that has saved tens of thousands of lives in the past three years. They say research is under way on a wearable device that could detect overdose and automatically inject the drug.

A medic with the Cincinnati Fire Department administers naloxone to an overdosing man, 2017. Naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan, blocks opioid receptors and so counters the potentially fatal breath-suppression effects of the drugs.

In the field of drug treatment new methods have been developed for delivering a version of Suboxone, which, like methadone, prevents withdrawal symptoms and can help people stop using heroin and stabilize their lives. Long-term use of opioids such as methadone still carries the stigma of moral weakness; critics describe medication-assisted treatment (MAT) as simply replacing one bad substance with another rather than addressing the root causes of addiction. “Opiates take my soul,” said Salop, who often used Suboxone to stave off the agony of withdrawal. “That’s not recovery. That’s prolonging the inevitable.”

Yet studies clearly show MAT is remarkably effective at reducing overdose deaths. Experts say ending the epidemic will require a broader acknowledgment that many users are unable to abstain from opioids the way Salop and Marshall do, but can build healthy lives by using methadone daily the way others take insulin or statins.

“Addiction’s a chronic disease. We’ve been treating it as an acute disease for way too long, and we can’t do that,” said Joseph Garbely, medical director at Caron Treatment Centers, where Salop began his recovery. “It’s a relapsing, remitting disease like multiple sclerosis or diabetes or hypertension, and we have to start treating it as such.”

NIH and NIDA officials say additional new drugs are being studied that reduce cravings or block the effects of opioids. At the same time, they acknowledge new treatments may be irrelevant if users can’t access them. Methadone and Suboxone have already been available for many years, as has naltrexone (Vivitrol), which prevents opioid molecules from attaching to opioid receptors. “These medications coupled with psychosocial support are the current standard of care for reducing illicit opioid use, relapse risk, and overdoses, while improving social function,” they write. “However, limited access to providers and programs can create barriers to treatment.”

That is, people can’t afford the medicine, don’t live near a treatment facility, or don’t get the help they need to visit a doctor. One recent study found that Staten Island, an opioid-plagued borough of New York City with almost half a million residents, has only two methadone clinics. Drug rehabilitation centers are also scarce in many places, particularly rural areas, where some users must spend hours driving to appointments, assuming they have cars. They may not have health insurance or cash on hand. Public programs provide only limited services at most, yet many people need months of treatment to truly recover.

“If we had all of the money and all of the resources available to us, we could end it pretty fast,” D’Orazio said of the epidemic. “But it’s going to cost so much in time and resources to overcome the problem that it’s going to be very difficult to do so rapidly. Everybody that’s involved in this knows what it takes, and everybody knows we don’t have the resources to do that.”

Harm-reduction efforts, which aim to keep users alive and safeguard their health, also face barriers to expansion. Programs that provide clean needles to users to prevent the spread of HIV and hepatitis have gained wide acceptance, but actual supervised-injection facilities have had a hard time getting off the ground in the United States despite successful precedents in Canada and Europe. Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney, anxious to reduce the number of fatal overdoses, endorsed the idea of having a nonprofit organization open what he calls a comprehensive user-engagement site, but the proposal has faced pushback from the state attorney general, police officials, city council members, and neighborhood residents. The U.S. Department of Justice has warned that such facilities would violate federal law, and critics argue they would encourage drug abuse and cause blight. At the same time, the crisis has become so devastating that the need for such sites may overcome even these hurdles. Some recovery advocates are ready to push for even more radical advances, such as providing heroin-assisted treatment when methadone and other medications are ineffective, as is allowed in some other countries.

Kensington resident Cecilia Ortiz speaks against a proposed supervised-injection facility at a March 2018 town hall meeting. City health officials and Mayor Jim Kenney have thrown their support behind the idea, which would be the nation’s first such facility given official sanction, but many neighbors fear it would draw more crime and instability to a community that has already been hit hard.

On the prevention side, states now have prescription-monitoring programs to identify overprescribing doctors and patients who go doctor shopping. Some states and insurers, and at least one pharmacy chain, CVS, limit prescriptions to a few days’ worth of opioids, which will hopefully prevent surplus pills from falling into the wrong hands. But many more prevention measures are needed: not only must doctors do a much better job of screening patients for addiction risk, but schools and other institutions need to identify and help at-risk kids before they develop drug disorders. Screening, education, and early intervention are vital, as they are virtually the only ways to keep young people from using opioids. Last year Massachusetts began universal screening of middle-school students, using a questionnaire and intervention protocol; other states should do the same.

With adults prevention is more challenging but perhaps even more important. Drug overdoses are killing Americans of all ages, with death rates of about 35 per 100,000 among people 25 to 54 years old. Middle-aged white men have been particularly hard hit, with a drug fatality rate that rose from about 8 per 100,000 men in 1999 to more than 26 per 100,000 in 2016. Many observers have asked how we can protect these men and why they are so attracted to addictive drugs in the first place. No other country has anything like our problem with opioids. What is it about the culture or economy of the United States that leads so many into such self-destructive behavior? If the sheer availability of drugs is the main cause of the crisis, why are certain groups more prone to succumb?

Biological and medical research can only go so far toward answering these questions. Understanding and addressing the epidemic requires consideration of its psychological, societal, and economic aspects. One popular, though contested, set of theories links addiction to a deficit in social bonding and feelings of self-worth. Economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton argue surging opioid overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related fatalities are “deaths of despair” resulting from wage stagnation and unemployment among non-college-educated men, along with the resulting family problems. One study found a 1% increase in a county’s unemployment rate is associated with a 3.6% rise in opioid deaths. Another study linked fatalities to low “social capital,” which includes such variables as the number of civic associations and voting rates.

“The drug becomes a part of you and you’re used to it. It becomes more important than food. If you could choose the drugs over oxygen, you would probably choose the drugs.”

Journalist Maia Szalavitz, who writes about neuroscience and addiction treatment, suggests a lack of social connection has deprived people’s brains of endorphins and the hormone oxytocin, inducing cravings for opioids as a replacement. “In essence, if we want to have less opioid use, we may have to figure out how to have more love,” she writes.

Quinones seems to agree but proposes a somewhat more specific solution. He essentially blames runaway capitalism and in particular the exaltation of the private sector—such as drug companies—over government and the public sphere. Private consumption and isolation are more valued than social connection and collective action. Heroin turns users into “narcissistic, self-absorbed, solitary hyper-consumers,” he writes. “A life that finds opiates turns away from family and community and devotes itself entirely to self-gratification by buying and consuming one product—the drug that makes being alone not just all right, but preferable.”

Changing this social dynamic would require a multifaceted, generational effort. In a recent Vox article on how to end the epidemic, experts said the nation must address factors that contribute to the misery and psychological fragility of many Americans, such as untreated mental illness, a weak social safety net, unsatisfying jobs, a lack of healthy recreation options, and poor support for families. After visiting cities in Ohio and Kentucky that are working hard to emerge from the crisis, Quinones reaches much the same conclusion: “The antidote to heroin is community,” he writes. Get out of your house, let your kids play in the street, join civic groups, improve your town, and find your joys in connecting with people, he says. And when adversity comes, face it; don’t hide in the false security of a pharmaceutical haze.