It began with an accident and ended with fire, two aging radicals scorched by riot, exile, and threat of imprisonment. Josiah Wedgwood and Joseph Priestley’s friendship lasted for decades; they were allies who worked for the abolition of slavery and strove for progress in all its forms—scientific, medical, technological, and social. They were icons of the Enlightenment, believing science and technology would pave the way to better and more comfortable lives, especially for the working classes.

Wedgwood and Priestley first met in 1762 after Wedgwood fell off his horse on his way to Liverpool. Roads at the time were atrocious. One traveler to Wedgwood’s hometown of Burslem measured the pothole that jolted his carriage: four feet deep. It was no great surprise then when Wedgwood’s horse tripped on a rut about 20 miles outside of Liverpool. Unfortunately for Wedgwood he fell on his bad leg, a legacy of a childhood infection.

His day only got worse. He rode on in pain to find a quarter of the town in flames, with people scrambling to gather their belongings and flee. Wedgwood found an inn safe from the fire, but the surgeon called to attend to his leg would not rule out amputation.

Despite the misery of the day the surgeon and the potter soon fell into conversation, discovering that both were Dissenters from the Church of England, liberal in their politics, and deeply interested in chemistry and education. The surgeon happened to teach at a nearby school for Dissenters and, once amputation had been ruled out, returned with a scientifically minded colleague named Joseph Priestley to help entertain the bored Wedgwood. The two would remain friends for the rest of their lives.

Josiah Wedgwood was born in 1730 as the last of 12 children to a family of potters. By age 10 he had survived smallpox and witnessed his father’s death, after which he was apprenticed to the new head of the family, his older brother. His job was to make up the glazes and create the molds for the clay. This was all cheap, coarse, black and mottled pottery, packed in straw, sent off in carts over the rough dirt roads, and often subject to breakage. (Wedgwood would later support the building of roads and canals, believing them essential to the success of British industry in general and his own in particular.)

The pottery sold for barely enough to feed the family. The youngest Wedgwood had ideas to improve the quality of the family’s ware, but his brother stuck grimly to traditional methods. Still, the Enlightenment, with its new ways of doing things, was in full swing, reaching even as far as the small town of Burslem in the West Midlands. A cousin of Wedgwood’s believed potters should have knowledge of chemistry and should study fire, clay, and minerals and learn to manipulate them properly. Wedgwood became a believer in the power of science to help industry. He read books on chemistry, experimented with glazes, and turned his kitchen into a workshop.

Priestley, three years younger than Wedgwood and also a Dissenter, had been groomed for the Calvinist ministry but ended up a Unitarian preacher. He was unpopular with his first congregation but found greater success with his second. In the late 1750s he established a school for children and, unusual for the time, taught them science. In 1761 Priestley was hired to teach modern languages and rhetoric at Warrington Academy. In between his teaching and preaching he experimented with electricity and was among the first to see a parallel between the forces of gravity and electricity. A few years later, after leaving Warrington, Priestley began his serial identification of gases, including what we now call nitric oxide, ammonia, nitrous oxide (laughing gas), sulfur dioxide, oxygen, and carbon monoxide, among others. His scientific prestige was such that the Royal Society made him a member in 1766.

Wedgwood, who had left his brother’s workshop and started his own pottery business in Burslem, was seemingly destined for a life of hard work, moderate wealth, and little in the way of prestige. But his ambitions proved larger. Priestley helped Wedgwood in his pursuits, offering chemical advice in letters the pair exchanged; Wedgwood later repaid his friend’s kindness with shipments of retorts, crucibles, and other equipment for Priestley’s experiments.

Wedgwood’s own experiments were showing promise; he created pottery that in fineness rivaled expensive Chinese-made porcelain. (Years later, and after many attempts, he invented his famous blue-and-white jasperware, which is still made by the company he founded.) As the quality of his work became known, the English upper classes abandoned French and Chinese ware for Wedgwood’s. But the name Wedgwood truly became synonymous with fine ceramics when Josiah made a tea set for Queen Charlotte, wife of George III. She rewarded him with the title Potter to the Queen.

In 1769 Wedgwood opened a factory a few miles south of Burslem, next to a newly built canal—the highway of the 18th century—that would take his pottery on the first leg of a journey that might reach as far as America to the west or Russia to the east. In 1773 Catherine the Great, empress of Russia, commissioned a service that contained more than 950 pieces and paid the enormous sum of 2,700 pounds. Wedgwood used the opportunity to showcase the English country garden and home and illustrate Britain’s growing industrial might by depicting a canal, a dockyard, and a colliery in Catherine’s dishes.

Wedgwood built one of the first factories in the world, and he used it to take advantage of the public craze for decor inspired by ancient Greek, Etruscan, and Roman art. He was also one of the first to employ Adam Smith’s ideas about the division of labor to increase worker efficiency. Wedgwood’s concern was not just for production and profit; he created a system of health care for his employees that continued through their retirement. He wanted factories that reduced occupational health hazards, such as dust from the grinding of flint stones, lead in glazes, and smoke. Priestley pitched in and tried to come up with a way of providing healthful oxygen for Wedgwood’s factory, but the scheme proved impractical. According to historian Brian Dolan, author of Wedgwood: The First Tycoon, Wedgwood “would eventually consider the persistence of diseases amongst his workers one of the most disappointing failures of his career.”

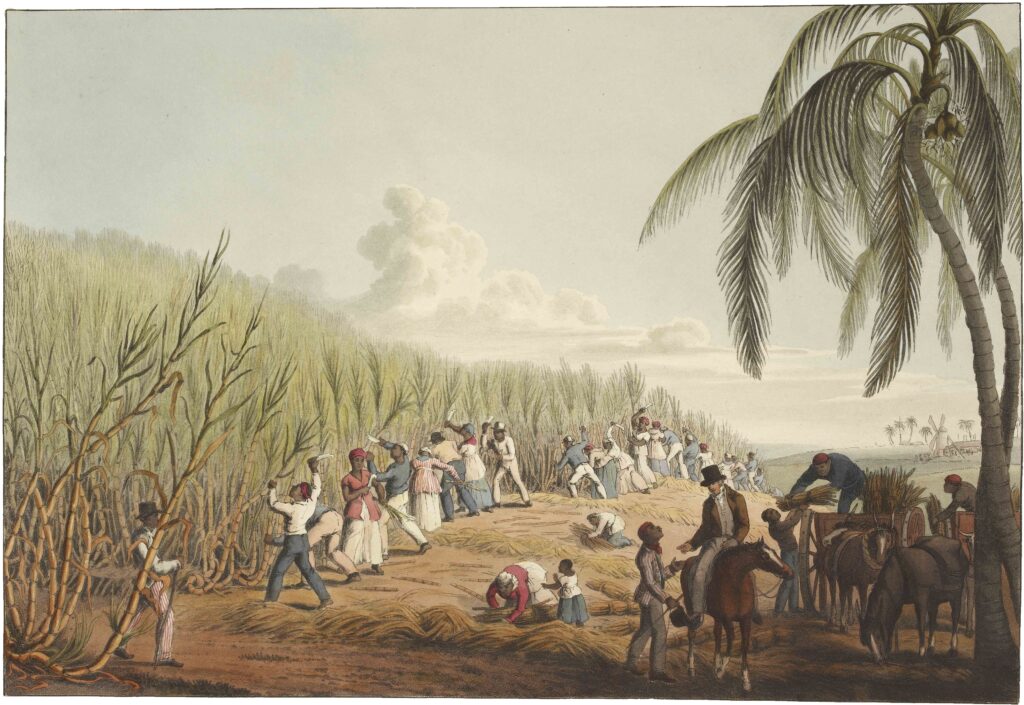

Enslaved workers cutting sugarcane in the British colony of Antigua, illustration by William Clark, 1823. Priestley and Wedgwood abhorred slavery and used their influence to fight its practice.

Wedgwood’s humanitarian impulses and Enlightenment beliefs even materialized in his pottery. In 1787 he mass-produced jasperware medallions for the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, of which he was a member. The medallion carried the image of a kneeling black man in chains and the powerful motto “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” A year later he sent some of his medallions to Benjamin Franklin, then president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery. Franklin thanked Wedgwood for the medallions and added, “I am persuaded [the medallion] may have an effect equal to that of the best written pamphlet in procuring favour to those oppressed people.” Priestley denounced slavery in his own way, preaching against it and publishing A Sermon on the Subject of the Slave Trade.

Priestley didn’t just preach. He also wanted to help his fellow man (and woman) by applying his science to improving public health at a time when cities had no garbage collection, little in the way of sewage control, and raging epidemics. He invented artificial carbonation in the belief fizzy water, which at the time could be got only from natural springs, could cure many illnesses. In his study of the workings of the natural world, including what we now call photosynthesis, Priestley saw a godly benevolence that was mirrored in the human world. As human health could be improved, so could moral and political health. When the American Revolution broke out, Priestley cheered it on.

In 1780 Priestley, by then well known for both his science and his unorthodox religious and political beliefs, moved to Birmingham, about 40 miles south of Burslem. At the time of Priestley’s move Birmingham was beginning its industrial rise. Nothing represented that rise better than the Lunar Society, which included James Watt (creator of the first efficient steam engine) and his business partner Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin (doctor, writer about evolution, and Charles Darwin’s grandfather), James Keir (chemist and industrialist), and, of course, Wedgwood. The Lunaticks, as they called themselves, met on the Monday closest to the full moon. After Priestley’s arrival in Birmingham they quickly invited him to join their company.

Priestley acted as a consultant for his friends’ activities, analyzing clay samples for Wedgwood and advising Watt on gases. Wedgwood helped support Priestley with 25 guineas a year (a sum worth a few thousand dollars today) until Priestley’s death.

In 1789 the French Revolution began with great hopes for political and economic reform. In England both Wedgwood and Priestley supported the uprising, as did many other reform-minded Britons, such as parliamentarian and antislavery advocate Charles Fox, in the belief France would duplicate the British Parliament’s bloodless dethroning of King James II a century earlier. In England those shut out from power—Dissenters, the lower classes—looked to the French Revolution for inspiration. Wedgwood even produced jasperware medallions that celebrated the revolution. But soon, even before war with France broke out in 1793, the backlash began.

The government, using spies and informers, arrested and convicted reformers on flimsy evidence. A few of those seized, such as minister Thomas Palmer and lawyer Thomas Muir, were transported to the penal colony of Australia. British reformers were compared to violent French Jacobins, and their ideas were condemned. Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, published in 1791, was judged seditious, and Paine himself was convicted of sedition against the Crown. Much of the fury against reformers and intellectuals more generally was a belief that the unfettered pursuit of knowledge was a cause of the tumult in France and would likely cause general disorder in Britain. Even some intellectuals turned against the pursuit of knowledge, especially when those pursuing it belonged to the laboring classes. John Robison, who had contributed many entries on science to the Encyclopedia Britannica and was a well-known professor at the University of Edinburgh, wanted circulating libraries and reading societies shut down. After all, who knew what dangerous knowledge was being spread to artisans and laborers and what they might do with it?

Black basalt stoneware medallion of Bacchus and his lion by Wedgwood and Bentley, ca. 1772–1775. Wedgwood rode Britain’s obsession with neoclassical design to wealth and fame.

While both Wedgwood and Priestley were distressed by the darkening political landscape, it was Priestley, the acknowledged radical, who faced the greater danger. In 1791 a mob enraged by his pro-French sympathies and quietly encouraged by local authorities burned down his house and laboratory and destroyed the chapel where he preached. Other prominent Dissenters and their property were attacked over the next two days. Wedgwood worried his factory might be next.

Priestley fled to London and never returned to Birmingham. The Lunaticks provided financial support and equipment, allowing Priestley to continue his scientific work. But as the political climate grew worse in 1792 and 1793, Priestley prepared to emigrate. In April 1794 he and his wife abandoned England for Pennsylvania. Soon after, Wedgwood learned he and like-minded men were to be marked for imprisonment if the French succeeded in landing on British shores. But that worry was soon put aside for a greater one. In November, Wedgwood fell seriously ill. On New Year’s Day he slipped into a coma and died two days later.

The two friends are today remembered for their scientific and commercial successes, respectively. Their attempts to make the world a better place are mostly forgotten.

In the printed version of this article, we gave an incorrect number for the children in Josiah Wedgwood’s family. We regret the error.