Jennifer Ray was in constant pain. Sometimes it was a low-level burning sensation like lemon juice on a wound; sometimes it was far worse.

Ray has complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), a little-understood disorder in which pain starts in one part of the body—usually at the site of an injury—and then spreads. In Ray’s case she was diagnosed following a knee operation at 16.

“I felt more pain as I progressively healed,” she remembers. Ray, now 31, was also diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and struggled with digestive problems. She often had to go to the hospital for a feeding tube because she couldn’t hold down food. Her constellation of problems all related to a central nervous system gone haywire.

She finally found relief from a surprising source: ketamine.

“It’s incredible what the life change has been,” she says.

Ketamine has been used as a surgical anesthetic for more than 50 years, but lately it’s finding uses outside the operating room. Doctors have discovered it’s surprisingly effective for treating depression and other mood disorders, so much so that in 2019 the FDA approved a nasal-spray version of the drug to help manage depression. But ketamine’s effect on difficult-to-treat chronic pain disorders, such as CRPS, fibromyalgia, and migraines, has remained under the radar.

“It is being used all the time for chronic pain,” says Steven Cohen, an anesthesiologist at John Hopkins Medical Center, who coauthored guidelines on the intravenous use of ketamine for chronic pain.

Ketamine works by blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, proteins in nerve cells that play a role in sensitizing the nervous system, says Cohen. The drug can halt that progression of pain sensitivity and even reverse it.

“People will often use the term rebooting the nervous system,” he says.

Ketamine has also attracted attention because it offers a new tool to treat pain at a time when opioid use is being scaled back. Unlike opioids, ketamine does not cause physical addiction. But it’s not without its own challenges. The drug has a good safety record in traditional clinical settings, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t potential for abuse. Ketamine is used as a party drug—often called “special K”—that produces a dreamlike, hallucinatory state called dissociation that makes the user feel disconnected from self and surroundings.

And its ability to address pain and depression has led to a smorgasbord of treatment offerings, with clinics selling ketamine infusions popping up all over the country. These clinics may or may not follow best practices for infusion of a drug that can put people into a terrifying mental state.

Steve Mandel, an anesthesiologist who cofounded a chain of ketamine-infusion clinics in Los Angeles six years ago with his son, Sam, helped establish the American Society of Ketamine Physicians. Mandel and other members of the group have pushed to make the drug more widely available, but now they are finding some clinics are not managing the procedure well.

“It’s a lesson that you have to be careful what you wish for,” he says.

Delirium Was Minimal

In 1956 chemists at Parke-Davis (now part of Pfizer) synthesized a compound called phencyclidine that had unusual effects: it could make rodents act drunk and immobilize pigeons. The drug eventually landed on the desk of Edward Domino, a young professor of pharmacology at the University of Michigan. Domino, now in his 90s, was among the researchers who tested the compound on different animals and found it was a potent anesthetic in monkeys. The same effect occurred in people tested at a Detroit hospital: phencyclidine worked as a powerful anesthetic, but as Domino writes in his history of ketamine, it left people in a state of “severe and prolonged post-surgery emergence delirium,” marked by acute disorientation and erratic behavior as they came off the drug.

Phencyclidine caused so pronounced a delirium that some doctors proposed using it as a drug model for schizophrenia. That is, they thought phencyclidine might be able to reproduce certain characteristics of schizophrenia that would allow them to study the physiological processes involved.

But curiosity about phencyclidine was not confined to the lab. By the mid-1960s it was showing up on the streets of San Francisco under the name PCP, or “angel dust.” Around the same time, a consultant for Parke-Davis, Wayne State University professor Calvin Stevens, synthesized derivatives of phencyclidine with fewer long-lasting effects, thus reducing emergence delirium. One of his derivatives became ketamine.

Parke-Davis asked Domino to test ketamine on humans in 1964. He and anesthesiologist Guenter Corssen started with three volunteers at Jackson State Prison in Michigan. The results were remarkable, he writes.

“Frank emergence delirium was minimal,” writes Domino. “Most of our subjects described strange experiences like a feeling of floating in outer space and having no feeling in their arms or legs.”

Though the effects were now less intense, drug company executives were still concerned about the trippy side effects. How could they describe ketamine’s effects without setting off alarms that would hinder the drug’s approval? Domino’s wife, Toni, suggested the term dissociative anesthetic, since subjects were “disconnected” from their environs. The term has stuck to this day—as have the concerns about the dissociative effects of ketamine.

That’s because in the 1970s counterculture personalities started to purposely play around with the disassociation, just as they had with PCP’s effects. Ketamine’s popularity in the United States as a party drug has waxed and waned in the succeeding decades, notably rising within the rave and dance club culture of the 1990s. And in that time it has also been put to more sinister use as a date-rape drug.

Nonetheless, ketamine has remained popular in hospital settings. Anesthesiologists like it because it doesn’t depress respiration; so it’s often used as a pain medicine in emergency situations for children, who are more sensitive to the adverse effects of opioids. Other medicines are used in concert with ketamine so patients don’t experience its dissociative effects.

Surprising Side Effects

In the late 1990s doctors began studying the beneficial side effects that seemed to occur even after ketamine was out of a person’s system. John Krystal, a neuroscientist at Yale School of Medicine, was studying ketamine as a way to model the feelings associated with schizophrenia when he found the drug had fast-acting antidepressant effects.

Around the same time, doctors in Germany found patients with a full-body version of CRPS could be cured of the syndrome if given daily anesthetic-level doses of ketamine for a week. The German research caught the attention of now-retired Drexel University neurologist Robert Schwartzman, one of the few Americans treating CRPS at the time.

Most doctors didn’t grasp just how much pain CRPS patients were in or even the source of the pain, says Schwartzman. “It becomes overwhelming for most people,” he says, adding that CRPS’s tendency to spread to other organs still flummoxes doctors.

When Schwartzman heard of the German researchers’ success in treating the whole-body version of the syndrome, he started sending his worst-case patients to Germany. (He had no choice but to send them abroad because fully anesthetizing someone with ketamine to relieve chronic pain was not something the FDA would approve.) Most of these patients were cured.

Ketamine infusion is “the only thing that cures the total body [CRPS], really severe cases, that I’ve seen,” Schwartzman says.

Though regulations precluded anesthetizing patients, in the early 2000s Schwartzman started developing a protocol to infuse lower doses of ketamine into patients who were still awake. The protocol is used today by many clinics. Ketamine Wellness Centers, a chain of ketamine clinics headquartered in Arizona, used Schwartzman’s research in establishing its protocol, says CEO Kevin Nicholson.

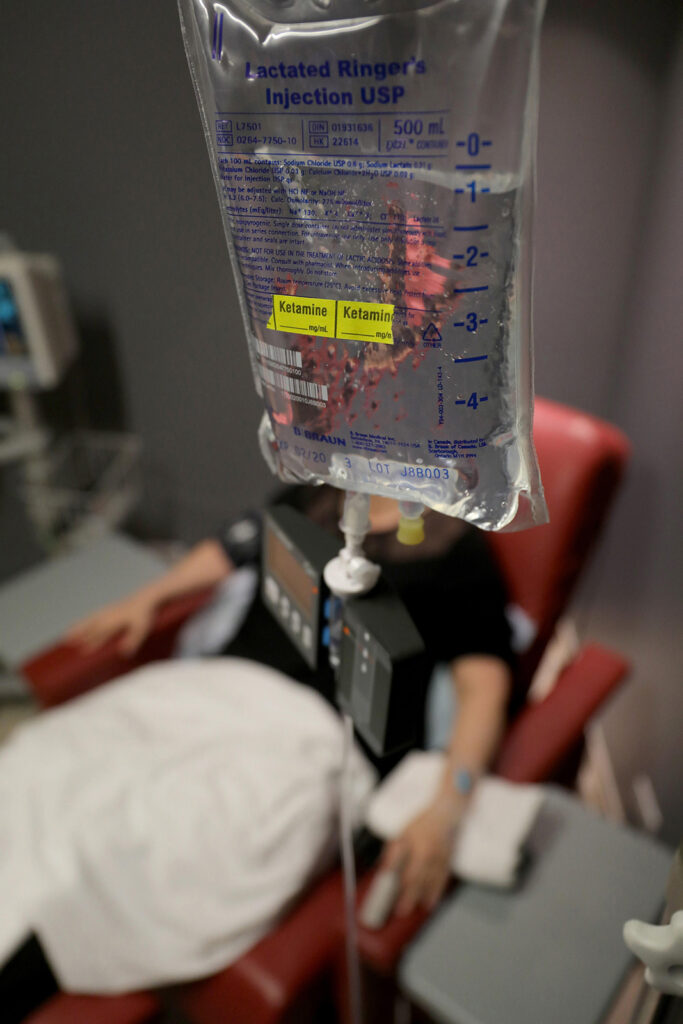

At Nicholson’s clinics a normal course of treatment for a patient with fibromyalgia, for example, would be a four-hour infusion five days in a row. During infusion patients are kept in a slight “twilight state”; they are made comfortable and encouraged to undertake a lighthearted activity, such as listening to music or watching television. A nurse or paramedic keeps watch the entire time, says Nicholson.

The dosages patients with chronic pain receive are a little higher than those given for depression treatments, Nicholson says. If the dissociative state becomes too intense for the patient, clinic staff will add an antianxiety medication to blunt the effects.

Nicholson says about a third of Ketamine Wellness Centers’ business comes from patients with a pain condition. That could include such disorders as phantom pain, fibromyalgia, trigeminal neuralgia, cluster headaches or certain migraines, and CRPS. The rest of the company’s clients are treated for depression or some combination of problems since pain and depression often go hand in hand.

Ketamine’s effects on depression have caught a lot of attention over the years because of how fast it can work, says Schwartzman, who would often field calls from psychiatrists curious about his ketamine infusion protocols. In 2006 neuroscientist Carlos Zarate Jr. led a team of researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health that found ketamine provided relief from depression and anxiety within a few hours. In contrast antidepressants could take two to three weeks to provide the same relief.

But when it comes to its effects on mental health, how does ketamine work? That “is a million-dollar question,” says Carolyn Rodriguez, an associate professor of psychiatry at Stanford University, who is studying ketamine’s effect on mood disorders.

The prevailing hypothesis has been that ketamine affects mood by blocking the receptor for glutamate, which is the most abundant chemical messenger traveling between brain cells, she says.

“But the action is complicated,” notes Rodriguez, “and ketamine acts on many different receptors beyond just the glutamate ones.”

For instance Rodriguez recently studied whether the body’s opioid receptors also played a role in ketamine’s antidepressant effects. When researchers blocked the opioid receptor, the antidepressant effects of ketamine were also blocked, “suggesting the opioid system plays a role in ketamine’s mechanism of action in depression.”

Multitasking Drug

Ketamine has many points of contact in the brain, not just glutamate and NMDA receptors, says Rodriguez.

“Because this drug acts in so many different ways, it may be helping people, but it may be helping different people in different ways,” she says.

Rodriguez has studied the effects of ketamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). As a clinician she had been frustrated with the months of waiting before first-line OCD drugs started working. Animal models have shown that glutamate plays a role in obsessive-compulsive behaviors just as it does in depression. Rodriguez figured the drug might also provide a fast-acting alternative to treat OCD by blocking glutamate.

Patients in Rodriguez’s first study saw immediate results. “They said this is like a vacation from my OCD.”

Rodriguez and her colleagues are now conducting larger, placebo-controlled studies while also using magnetic resonance spectroscopy to study the mechanisms by which ketamine works in the brain.

Researchers are still trying to understand how ketamine blocks both pain and depression, and there may be more at play than the blocking of a few types of receptors. Mood affects how people feel pain and vice versa. Mandel, the Los Angeles–based clinic operator, says the mental state of the patient has enormous effects on the treatment efficacy.

Cohen says pain has an emotional context. “If you’re very fearful and anxious, that amplifies pain,” he says. By somehow working on both mood and pain sensitivity, ketamine is all the more effective as a treatment.

Jennifer Ray can certainly speak to the connection between pain and emotion. Ray has received more than 40 infusions at the Phoenix outpost of Ketamine Wellness Centers and agrees patients must be in the right mindset for the treatment to be most effective. Ensuring a stress-free experience can be complicated, though, when you’re using a drug that can muddle a person’s sense of time and space. Ray has experienced dissociative states from the treatments, but when that happens, she is made comfortable by the staff and relies on her favorite music and meditation techniques to deal with it.

“Everything around my environment is very stress free,” she says. And “what you do after the treatment is really important.” Ray will take a nap, cook a good dinner, and take a bath. “It’s just about me recovering.”

Navigating the System

Ray’s recovery is startling compared with where she started. She used to take more than 15 medications to treat her disorder. After her ketamine treatments she is now down to 2 drugs.

When Ray began going to Ketamine Wellness Centers, she did the five-day treatment, each day being a four-hour procedure. On day two she felt her pain increase, but by the third day she felt no pain.

“It was very euphoric for me,” she remembers.

But the euphoria doesn’t last. Unlike in Germany, where anesthetic-level doses cured most patients of their symptoms, pain patients in the United States more often require regular maintenance treatment. Ray typically has to return to the clinic every month for booster treatments consisting of two or three infusions. And it’s not cheap. Clinics charge anywhere from $300 to $5,000 for an infusion, says Nicholson. Ketamine Wellness Centers charge $750 per infusion. Ray’s insurance won’t cover her treatment, so she pays out of pocket.

Medicare reimburses clinics $300 for ketamine infusions, a very low rate for a treatment that requires hours of medical supervision, says Mandel, whose clinic does not accept Medicare patients. And because treatment is being given off label—meaning the FDA does not sanction the use of ketamine infusions to treat chronic pain or mood disorders—most private insurance companies either don’t cover the costs or offer only partial reimbursements. To get a treatment “on label” costs millions of dollars’ worth of clinical trials. Paying those costs doesn’t make financial sense for drug companies since ketamine is a generic drug: the potential profits just aren’t there. (Spravato, Janssen’s nasal spray analog of ketamine that was approved for treating depression in March 2019, is technically a new formulation, thus not considered a generic.)

Faced with high out-of-pocket costs at private clinics, some patients may seek treatment at the emergency room. That was the case for Todd Wulf, a patient with CRPS in Washington State.

Wulf, who is 37, discovered ketamine’s benefits through a fluke. He had gone to the emergency room for pain in his groin related to his CRPS. But when doctors there tried to numb his groin with a nerve block, it had the opposite effect.

“I ended up in the ER screaming uncontrollably,” he recalls. They gave him an injection of ketamine that caused dissociative effects so intense he continued to scream for an hour. “But after that I felt no pain at all whatsoever for about a week.”

Wulf’s story is indicative of how dysfunctional the health care system can be when it comes to treating pain. By all indications ketamine should be a first-line treatment for chronic pain related to central nervous system disorders, but patients still end up finding it by chance.

Wulf developed CRPS after a work accident and subsequent surgery during which the doctor partially clipped a radial nerve. His hands and feet hurt the worst, though the pain is very different in each. His hands feel like they’re being squeezed and crushed, but that’s just the beginning. “It feels like I’m also dipping them in a deep fryer while that is happening,” he says. And if anything touches him, it feels like “being cut, deeply.”

The sensation in his feet is opposite but equally terrifying. He says it feels like he is “in a snowbank all the time” or has bees stinging him. If his feet are touched, he says it feels like someone is ripping off his skin.

Following Wulf’s first experience with ketamine his pain returned after a week; so he has sought out ketamine injections in subsequent trips to the hospital. Getting a direct shot of ketamine causes more anxiety-inducing side effects since it’s not a slow infusion like those given at ketamine clinics. Wulf says side effects last about an hour.

“And then you’re just fine; it’s like the whole thing just resets me,” he says.

But getting consistent treatments at the emergency room is not viable—some doctors have refused to give him ketamine—and Wulf can’t afford to pay the out-of-pocket fees charged at Ketamine Wellness Centers and other clinics.

His pain management doctor has recently given him ketamine cream, which seems to help as well. It works better than the high doses of opioids he has taken in the past, which he says do not provide anywhere close to the relief he gets from ketamine.

“Last couple years it’s been very rough, in and out of the hospital. I tell you, I wish I had known about this five years ago.”

Buyer Beware

Medicare’s low reimbursement rate for ketamine infusions has created a class of providers looking to make money by churning through patients, though most of these clinics target people with depression, not chronic pain, Mandel says. Such providers may not provide appropriate doses to pain patients, especially if sessions last only an hour.

That was the case for Jennifer Ray when she was introduced to ketamine. A local chiropractor was offering the shots. Her first experience was “brutal,” causing anxiety that inflamed her chest wall. “They pushed the meds too quick and too heavy,” she says.

Mandel says the American Society of Ketamine Physicians is working on a certification process and minimum standards for clinics. Professional organizations, such as the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the American Psychiatric Association, have released dosing and treatment guidelines for ketamine use in the past few years. But with the FDA steering clear of any regulation of clinics, it’s buyer beware.

Other concerns linger. Ketamine does not cause addiction the way opioids do, but it’s not without its risks for abuse. And long-term use of high doses of the drug can cause cognitive impairment and bladder inflammation, as noted in the American Psychiatric Association guidelines.

There is very little information about the effects of long-term ketamine use at doses given in a clinical setting. For this reason Rodriguez says caution is warranted when it comes to repeated administration. But again it’s unknown how much ketamine patients will have to take to address their different disorders in the long term. Rodriguez saw OCD patients respond well for long periods after their initial ketamine dose. One of her patients checked in six months after the study and was still functioning well. This patient was able to garden, something OCD had made impossible before.

Ray is hoping to go longer without needing ketamine infusions, but for now she is just grateful for what the treatment has done for her. She finds the treatments make her mindset stronger so when she does feel pain, it doesn’t seem as bad.

Rodriguez also remains optimistic based on what she has seen.

“Being able to see somebody feel better in hours and not have those OCD thoughts just gives me a lot of hope and makes me think that we’re on the right track.”