Judith Kaplan and James Voelkel, historians at the Science History Institute, sit down to talk about the overlap of science and magic in early modern Europe and how our understanding of those entangled practices has changed over time.

Judy: Hi, Jim. So, what rare books have you been reading lately?

Jim: Well, I was just looking at this English translation of Giambattista Della Porta’s Natural Magick. A hundred years had passed since it was first published in Latin in 1558, but it was still worthy of translation.

Judy: Oh, yeah? That’s a funny title when you stop and think about it—it sounds like an oxymoron. How do you understand “natural magic”?

Jim: Natural magic harnesses nature’s hidden powers to miraculous effect, though some examples of magic are more miraculous than others. For instance, Della Porta says you can preserve cucumbers for some time by putting them in brine. So the mundane transformation from fresh to pickled cucumber is an act of natural magic. The more important thing is that these natural powers aren’t obvious; they’re hidden. The Latin word for hidden is occultus, so these hidden powers were called “occult,” though they didn’t mean anything spooky by it. That said, the counterpart of natural magic is demonic magic, which is literally the result of action by demons.

So I was just revisiting this gem of a book, and I ran across one of my favorite oddities of early modern science.

Judy: What’s that?

Jim: The weapon salve.

Judy: I’ve heard of this! It has always sounded fun.

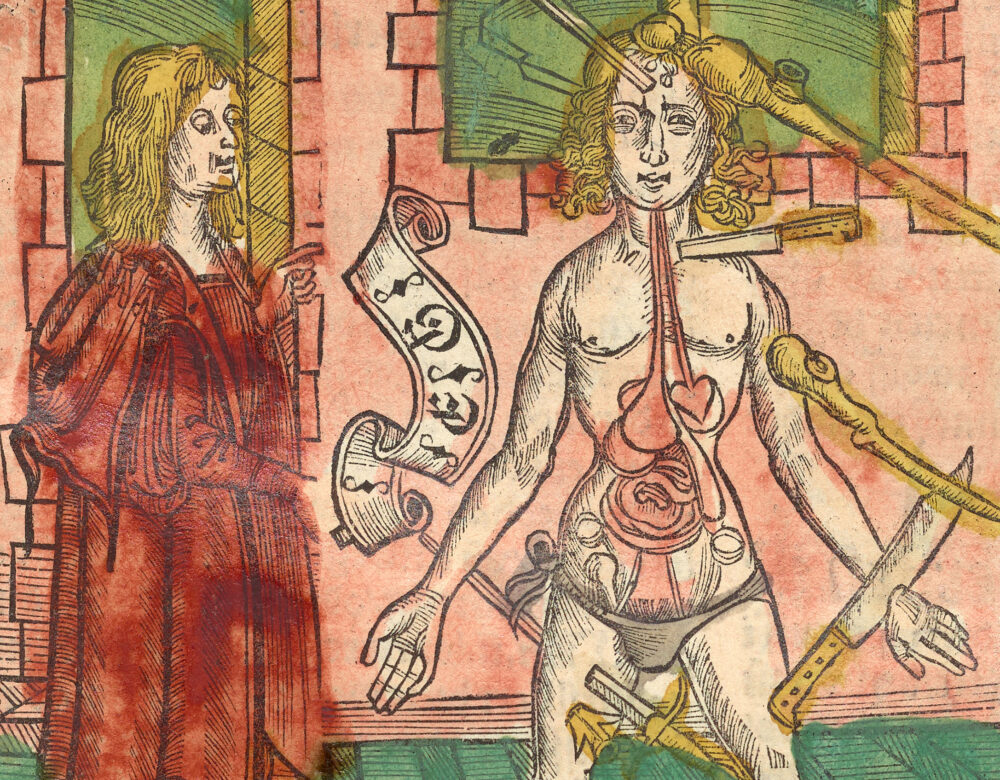

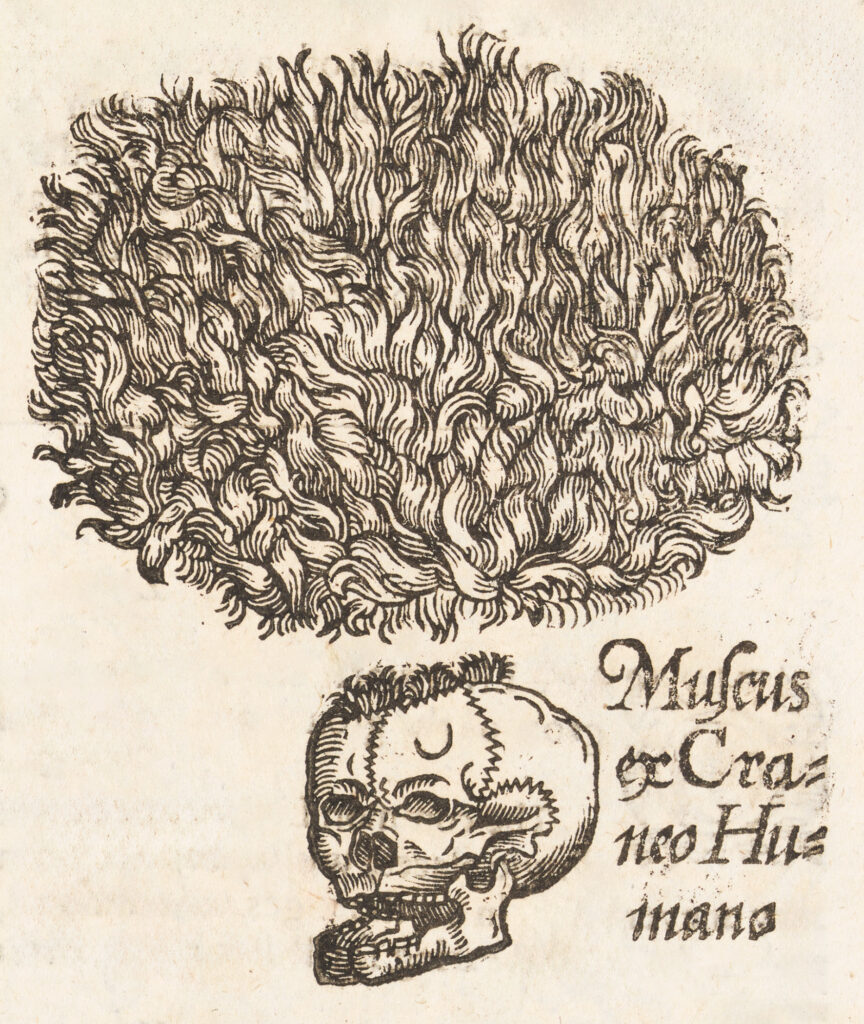

Jim: Della Porta gives the recipe here: “Take of the moss growing upon a dead man his scull, which hath laid unburied, two ounces, as much of the fat of a man, half an ounce of Mummy, and man his blood: of linseed oyl, turpentine, and bole-armenick [a medicinal clay], an ounce; bray them all together in a mortar, and keep them in a long streight glass.”

Judy: Oh my gosh, “half an ounce of Mummy”?! And again, I’m hung up on the name. This is a recipe for treating weapons?

Jim: Basically, yes. The idea was that if someone was injured, say, by a sword, you would just wrap the wound and let it be. Then you would take the salve and apply it to the sword—preferably still bloody. By the hidden—occult—powers of nature, the wound would be cured. What’s more, it even worked at great distances.

Judy: Wow. You mean it would work even if the weapon and the victim were in different cities? And this would go for a club or an arrow, too?

Jim: Sure.

Judy: You said the weapon salve is one of your favorite oddities. When did you first learn about it?

Jim: It was when I was a student at Cambridge, pursuing a second undergraduate degree in the history and philosophy of science. I was attending Simon Schaffer’s lectures on what’s called the Scientific Revolution. Amid all the other things that made science “revolutionary” in the 16th and 17th centuries—the realization that the earth goes around the sun, the overthrow of ancient textual authorities, the turn to experimentation, the development of classical mechanics (think: Newton’s law of universal gravitation)—Schaffer mentioned the weapon salve. He also mentioned sardonically that the only reason it worked was that it kept people from applying any worse treatment to the wound itself.

Judy: Funny, but we’re not supposed to judge people in the past by truths that hold today, right?

Jim: Well, he wasn’t wrong: the efficacy of the weapon salve was widely accepted, and it does seem like it would come down to that fact. Schaffer is now quite distinguished, but when I first met him in 1984, he was only four years out from his PhD. He was charismatic and irreverent, and to a relative naïf in the history of science like myself (my first degree was in astronomy and physics), the idea of the weapon salve was so outlandish I could only think that he was having us on.

When I went on to pursue a PhD in the history of science at Indiana University in 1986, the Scientific Revolution was taught by the distinguished Newton scholar Richard Westfall. In contrast to Schaffer, Westfall put the weapon salve clear out of bounds of anything approaching science. In fact, in The Construction of Modern Science (1971), Westfall went so far as to criticize the great philosopher René Descartes for inventing mechanisms to explain long-accepted phenomena, both real and imaginary, without first scrutinizing their veracity.

Judy: Sounds like Westfall was embracing the “P”—the “philosophy”—in HPS.

Jim: That’s right. Indiana was a history and philosophy of science program. The two were meant to go hand in hand. The example of history was meant to illuminate how science operated. Bizarre, extra-scientific ideas like the weapon salve just didn’t seem very fruitful in that context.

Cambridge was also a history and philosophy of science program, but Schaffer was at the forefront of a movement that was intent on showing how science was profoundly shaped by the society around it. I was at the tail edge of a generation who thought that a prerequisite for graduate study in the history of science was a degree in science—my background was in astronomy and physics after all. In that kind of atmosphere, we just didn’t have much time for an episode that was so obviously “unscientific.”

Judy: Yeah, Schaffer’s perspective had definitely become mainstream by the time I entered graduate school at the University of Wisconsin in 2004. Contextualizing science was the name of the game, and we were accustomed to thinking with the “symmetry principle”—basically the view that both “true” and “false” scientific theories have rational and irrational reasons for being. According to this fundamental symmetry, both were fair game for historians of science.

Though I can’t recall discussing the weapon salve specifically in my coursework, we spent a lot of time thinking about wondrous monsters, phrenology, charismatic healing, and other seemingly odd pursuits. We took these ideas seriously. This work pushed us to think about what “science” meant to the people who were practicing it, how it was paid for, how it was received by the public, stuff like that.

Jim: That makes me think of our Digbys—sorry, our collection of books by Kenelm Digby.

Judy: Oh, I know this guy! He was an occultist and pirate, right? Didn’t he fake his own death at one point?

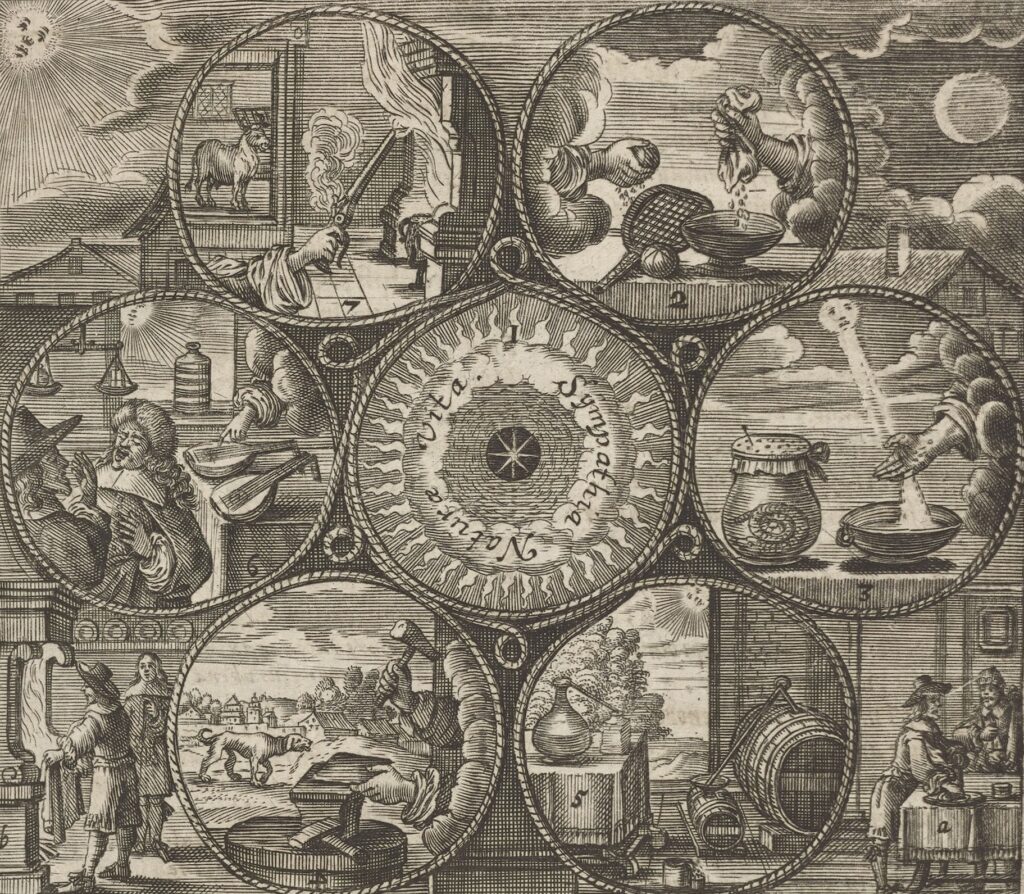

Jim: Yes, the very same. When I joined the Institute in 2008, I noticed pretty quickly that our rare book collection had a lot of editions of books by Kenelm Digby. He promoted a variant of the weapon salve in the mid-1600s, the “powder of sympathy” or “Digby’s powder,” turning a scientific curiosity into a broader sensation. Despite publishing a full century after Della Porta, he claimed to be the first person in Europe to know about it, having learned the recipe from a monk recently returned from “the Orient.” In all, there were 40 editions on Digby’s powder in five different languages.

Judy: I can see how he’d be a prime example of this “science in society” approach. All of those Digby books reflect a voracious public appetite for healing at a distance. This really cries out for some kind of explanation. It can’t simply be the case that people were more credulous in Digby’s day.

Jim: Right, it is important to remember the dictum my old friend David McGee used to tell his students: “The reason science has a history is not that people were stupider back then.”

Judy: Yep, so coming back to Schaffer’s class, then, the question is how did the weapon salve and Digby’s powder of sympathy fit into the logic of the “Scientific Revolution”? We, as historians, shouldn’t ignore it or try to explain it away.

Jim: As outrageous as the idea of the weapon salve seems, it “fit,” so to speak, with all kinds of research into occult powers pursued in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was not inherently implausible. There were many phenomena whose effects were apparent but whose causes were mysterious.

The barometer and the air pump had just been invented, and people were using them to investigate atmospheric pressure and the properties of gases. A question of particular interest was what unseen power held up the column of mercury in a barometer.

William Harvey had discovered the circulation of the blood, and physiologists were trying to figure out what function it served the body. Similar questions about the function of respiration were not far behind.

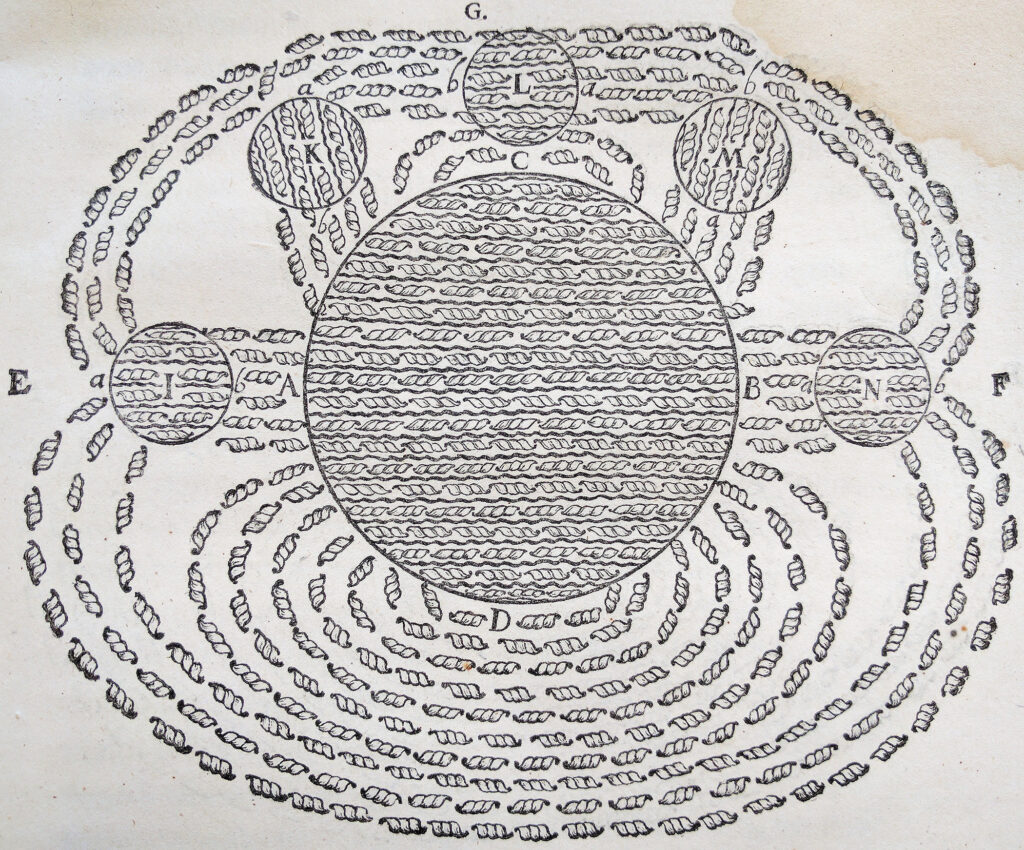

Then there was static electricity, which caused some things to be miraculously attracted while others were repelled. And there was magnetism, which had similar attraction and repulsion, but could also turn compass needles, which were an essential navigational aid.

At the turn of the 17th century, William Gilbert was able to show that compass needles point north because the earth itself is a giant magnet, but still no one had any idea what magnetism was. All these things and more were crying out for explanation.

Judy: Say more.

Jim: Well, look at Descartes’s Principles of Philosophy. It was one of the pillars of the new philosophy of science in the 17th century—the foundational work of trying to explain the phenomena of nature through mechanical causes. It was his antidote to the vague explanations proffered by earlier natural philosophers, who used Aristotelian explanatory principles. Aristotle came up with four different kinds of “why questions” to explain change, but the “final cause”—the end, or purpose—was the hardest. Why does an acorn grow into an oak tree? Essentially, because it is fulfilling its destiny. Why do heavy things fall or sink in water? Because they are seeking their natural place.

Descartes wasn’t the only one who was growing dissatisfied with these squishy causes. To get rid of them, he reduced the cause of every natural phenomenon to the action of matter upon matter. In the case of magnetism, he attributed what we perceive as attraction and repulsion to the circulation of imperceptibly small screw-shaped particles through screw-shaped pores in iron and other magnetic materials. Attraction occurred when the particles flowed from between two bodies into the pores; with their absence, matter on the other sides of those bodies would push them together. When particles accumulated between the bodies, on the other hand, they pushed the bodies apart, which we would perceive as repulsion. What explained polarity, as we now call it? Easy: these particles and pores were divided into two types, some with right-handed threads and some with left-handed threads.

Judy: Right, so tiny particles that you can’t see, causing effects at a distance. Not so different, I suppose, from applying the weapon salve to a spear in one room and a wound closing up in another.

What’s really interesting to me is how these self-declared experts tried to compare notes on phenomena they couldn’t see. How did they try to prove their theories and convince one another of their expertise? You find a lot of emphasis in the 17th century on the importance of observation, experiment, and firsthand witnessing. The “scientific revolutionaries” expressed a lot of contempt for old text-based authorities. So how did they reconcile the need to witness with the study of forces that you literally can’t see?

Jim: These kinds of questions play out in an exchange involving the weapon salve between Joan Baptista Van Helmont, a Flemish physician, and Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit polymath. On the surface, they are arguing about the weapon salve’s efficacy and cause, but really, these two were debating the scientific credentials of Jesuit authorities.

Judy: As I recall, Van Helmont used the scientific debate to ridicule Jesuit claims to philosophical rigor. You can see this in the language he uses. Here, in the 1621 treatise On the Magnetic Treatment of Wounds, he writes that the

The distinctions are nuanced, but he’s basically saying that natural magic can do a more credible job of explaining the weapon salve than religion.

Jim: Of course, the authorities didn’t take kindly to this philosophical trash talk. Van Helmont’s criticism of Catholic authority combined with his interests in occult phenomena like the weapon salve got him in trouble with the Spanish Inquisition. These philosophical debates could have dangerous consequences.

Judy: This reminds me of Galileo, whose conflict with the Catholic church arose not so much from saying that the earth goes around the sun as from asserting that he, as an astronomer, had the authority to say so, not the church.

Jim: But coming back to hidden mechanisms, Westfall’s critique of Descartes, on reflection, has a whiff of the science in society approach. His issue with Descartes is that he is credulous. Having come up with the revolutionary framework of mechanistic explanation, Descartes just goes on to apply it to all the phenomena commonly accepted by everyone else. Westfall skewers him for allowing that Van Helmont’s “absurd” account of why a corpse’s blood would run when its murderer approached is amenable to mechanistic explanation. And though Descartes was silent on the weapon salve, Westfall extended his critique to the following generation who did come up with mechanical explanations of the salve.

Judy: I’m constantly struck by the violence in this history. From extracting mummia, presumably from tombs, to collecting moss from skulls, presumably from executed criminals, and now this account of murder and miraculously flowing blood.

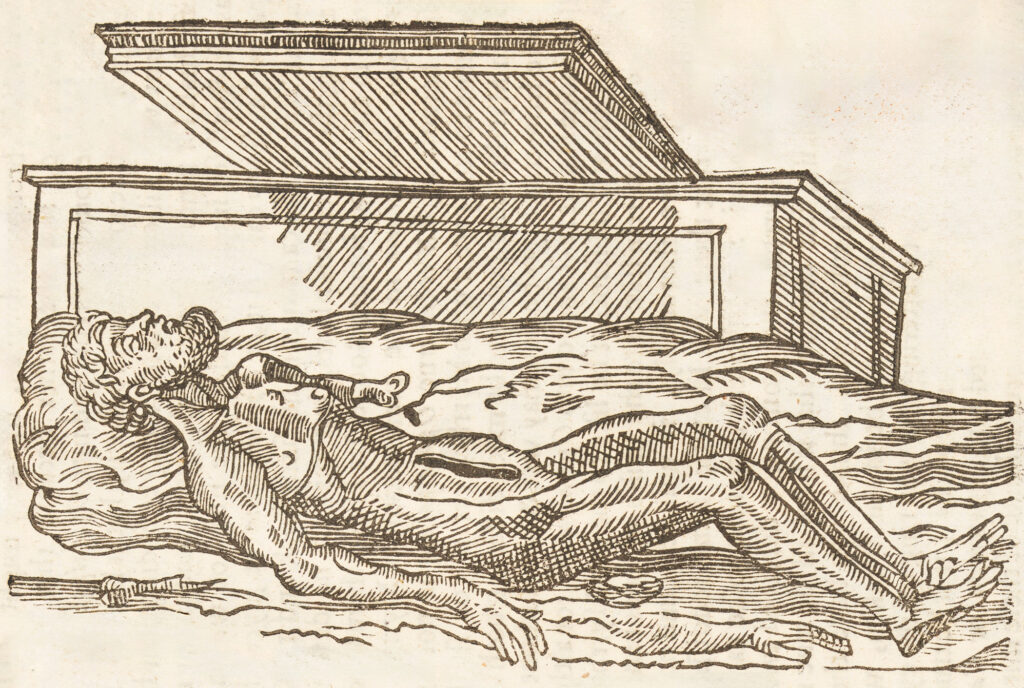

Jim: I know! I had a similar feeling recently when I was trying to find out more about this connection between Van Helmont and Descartes. I googled “blood running when the murderer approaches Van Helmont”—you don’t want to know the hits you get without “Van Helmont”—and I learned that this phenomenon in English is called cruentation. It derives from the Latin cruentare, to stain with blood, and has its own tiny entry in the Oxford English Dictionary. The word refers to the oozing of blood that sometimes occurs when an incision is made into a dead body. According to the OED, at one time it also was used to denote “the supposed ‘bleeding from the wounds of a dead person in the presence of the murderer.’ ”

Judy: That’s a good one. Can’t wait to use it in Scrabble.

Jim: Yes, in my family we used to call these “ten-dollar words.” But parlor games aside, the concept establishes a bridge from Descartes’s mechanical philosophy to the weapon salve, if only by association. It helps to further this idea that the weapon salve wasn’t an aberration in a period of rapid scientific development, it was very much born of early modern science.

Judy: And with Digby we also get the sense that science isn’t an exclusive domain in this period. The weapon salve began, it would seem, as a strange, but apparently effective, cure. It was, in certain respects, like magic, but it was similar enough to other natural phenomena, such as magnetism, to warrant serious philosophical investigation.

Jim: But after Digby came along, you could purchase a powder from your local druggist that would basically do the job. Mysteries were dispelled, sticky messes were cleaned up—all for, Digby says, 18 pence a pop! The success of his marketing, essentially, ushered the debate out of the hallowed halls of the natural philosophers and into the popular imagination. Fascination with it persisted for decades, just not so much among these early scientists.

Judy: So then we’re not left with much of a ending to this story, Jim. Help me out here.

Jim: It’s true, the story of the salve lacks a decisive resolution for us. By the early 18th century, the people who were writing about the salve were no longer natural philosophers. And this kind of brings us full circle in our discussion of the history of science. If we want to say that, historically, science is what scientists—a.k.a. natural philosophers—do, the weapon salve had escaped this realm. And wherever it went, we have not followed.