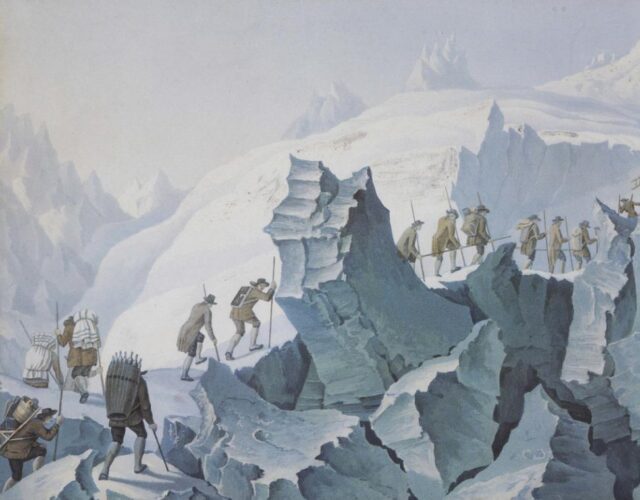

In August 1861 the terminus of the Glacier des Bossons at the foot of Mont Blanc yielded up the remains of two mountaineers. The discovery caused a sensation, for they were quickly identified as victims of the first notorious Alpine mountaineering accident, the so-called Hamel Catastrophe of 1820. Joseph Hamel (1788–1862) had led a scientific expedition in which three local guides were lost after they were swept into a crevasse following the party’s harrowing 1,200-foot fall in an avalanche.

The reappearance of their remains 40 years later was famously and accurately predicted by glaciologist James David Forbes. Two of the surviving guides were still alive, and one, 72 year-old Joseph-Marie Couttet, positively identified the remains. Recognizing a hand with part of an arm attached, Couttet remarked, “Who should have thought that I should have shaken the hand once more of my brave comrade, the pauvre Balmat!”

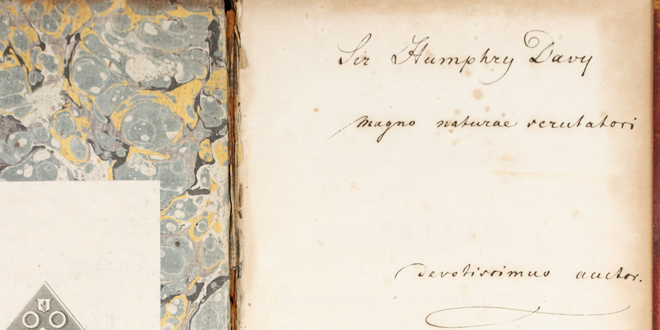

In 1813, on his first visit to England, Joseph Hamel presented this copy of his dissertation to Humphry Davy.

Hamel was still alive at the time. He never quite lived down his association with the accident (even Mark Twain wrote about it), though he did go on to become a cosmopolitan savant in the classic mold. Born in Sarept, part of a colony of Germans from the Moravian church, Hamel was both an ethnic German and a Russian subject. He trained as a physician, though he later became a member of the technical section of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences. He lived in England for many years—where he was an active member of the geographical society—studying British industry and collecting tens of thousands of British patents, undoubtedly to aid Russian industrial development. He traveled to the United States for the same purpose and in 1854 visited the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York. In Russia he wrote a notable description of the tsar’s Tula small-arms factory and a history of iron production.

The glacial saga began on his first trip abroad after earning his medical qualifications in St. Petersburg in 1813. Hamel went to England to introduce himself to the leading scientific elites of the day. As a calling card he brought a copy of his doctoral dissertation on the construction of braces, Dissertatio inauguralis medico-chirurgica de bracheriorum constructione (St. Petersburg, 1813), which he presented to Sir Humphry Davy, at that time perhaps England’s most prominent scientist. The Othmer Library of Chemical History is proud to possess that very copy of Hamel’s dissertation with the author’s inscription to Davy (in Latin) and the bookplate of Lady Davy. So far as we know, ours might be the only copy outside of Russia.