Making matches and matchmaking in India might seem as similar as chalk and cheese.

Matchmaking is emotional drama, the complex compatibility of personalities and families, famously narrated for international audiences by Sima Taparia of Indian Matchmaking. It calls to mind the resplendence of Indian weddings: gold jewelry, brilliant saris, rich foods, sacred fires. Matchmaking and the weddings that result from them are big business.

Few, by contrast, would think matchbook making a lucrative business opportunity. Matchsticks are simple, disposable, and utilitarian. Their chemical sparks pale in comparison to the famous romantic matches of Indian history, which have been told and retold over centuries, even millennia. Matchstick making in India has few historians. The humble matchstick cannot hold a candle to the matches orchestrated by the likes of Sima Auntie, whose television series essentializes contemporary India.

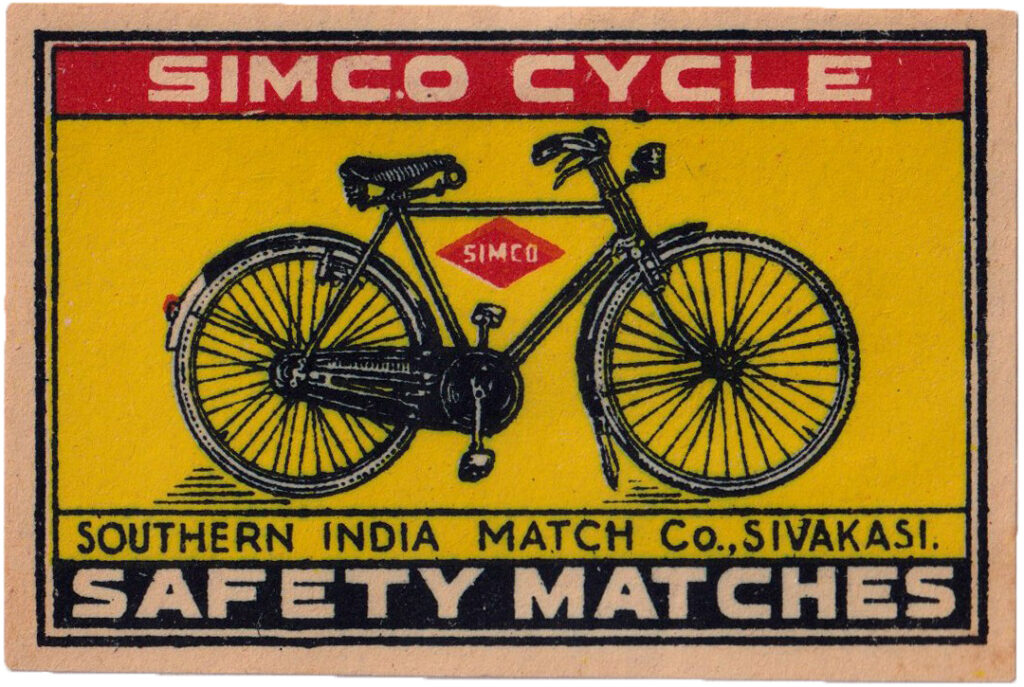

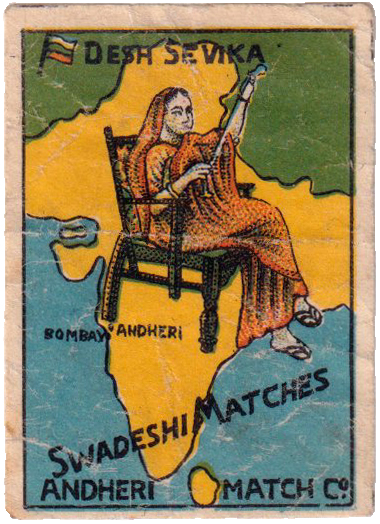

Yet matchsticks, specifically the books in which they came, were once a different kind of essentialized India. When the first Indian-made matchsticks appeared in the early 1900s, the matchbook covers were magnificent forms of mass-produced art. Phillumenist, or matchbook enthusiast, Gautam Hemmady has collected more than 25,000 of these labels over many decades. These miniatures transcended the boundaries of past, present, and future, featuring plants and animals of the Indian landscape, men and women of laboring artisan communities, as well as new machines and devices—bicycles, trains, pressure cookers, telephones, water pumps. Later in the 20th century, these commodified artworks captured the aspirations of the burgeoning nationalist movement.

Why would so much effort and detail go into illustrations for containers meant to be emptied and tossed? How did a technology as simple as the matchstick come to carry so many different meanings for the people of the Indian subcontinent? To understand this hidden richness, we must think of matchstick production in colonial India as revolutionary—both a revolution in the chemistry and mechanics of manufacture in the subcontinent and an upheaval in the global industrial economy at the turn of the 20th century.

Factories in Western Europe and North America began manufacturing matchsticks in the mid-1800s. The ability to mass produce these instruments of instant fire—given the nickname “lucifers” when they first gained popularity—was hindered by the complexity and expense of the chemistry involved.

The matchsticks that initially swept the market were made using white phosphorus, a highly toxic substance that sickened and disabled the laborers who came into contact with it. “Phossy jaw”—an excruciating condition in which inhaled phosphorus fumes eroded workers’ mandibles—became iconic for the perils of industrial labor in the period before workplace organizing and activism. The London matchgirls’ strike in 1888 was likewise emblematic of the working class’s discontent and instigated a wave of industrial agitation. Annie Besant, an important organizer of the strike, would go on to play an integral role in the home rule movement in India.

The safety match was developed in response to these industrial health risks by a variety of European chemists and industrialists, including Johan Edvard Lundström, who began manufacturing matches with non-toxic red phosphorus—placed on the striking surface instead of on the match head—in the 1850s at his factory in Jönköping, Sweden. An abundance of aspen forests made Sweden well-suited for matchstick manufacture; the softwood of aspen and its coniferous neighbors ignites easily. The Jönköping factory and its Swedish contemporaries would grow to dominate the 19th-century global market, producing roughly 50 billion matchsticks annually by the early 1900s.

Colonial India was a significant market for these matchsticks, and prior to the 1920s there was little local competition. Small upstarts in Gujarat and Bengal struggled for a variety of reasons, including access to softwoods, lack of chemical expertise, the costliness of industrial machinery, and a generally inhospitable climate for Indian entrepreneurs. In 1923 the Western India Match Company (WIMCO), a Swedish venture, incorporated near Bombay and would go on to hold a major share of the market for the rest of the 20th century.

However, the 1920s were also a turning point for local industry in India. The exigencies of World War I meant that many chemical goods that were normally imported had to be produced locally, drawing attention to both the lack of scientific expertise in India and British failures to stimulate industrial development in the subcontinent. In response, many of India’s provincial governments created departments of industries, opened vocational training schools, and created state aid programs for supporting fledgling businesses. One of these businesses was run by A. Muthiah Pillai, who in 1922 applied for government aid for a matchstick business, located in what is now southern Tamil Nadu.

While a state aid application might at first seem an unlikely place to understand how a local matchstick industry became rooted in India, the exhaustive 20-page exchange between Pillai and the government reveals much about the difficulties of starting a manufacturing business in this place and time.

The documentary record shows that the matchstick business would be headed by Pillai, with the pyrotechnic work overseen by his son M. Visvanatha Pillai, and capital investment provided by one Subramanya Chettiar. The government’s Development Department was generally supportive of such enterprises, especially those in the realm of chemical industry. However, colonial officials were also disinclined to financially entangle themselves with the affairs of individual proprietors, and would thus scrutinize each application carefully, corresponding with the applicants for months and even years before approving any request.

Rather than ask for a loan, Pillai requests access to the lumber from the Cumbum Forest, a government reserve, arguing that the cost of taxes and Forest Department license fees would otherwise undermine the profitability of his venture. Pillai’s request sets off an intense discussion about the kind of trees suitable for matchstick making. Two potential species—the Malabar silk-cotton tree (Bombax malabaricum) and the bhutyā tree (Sterculia urens)—did not grow in a concentrated fashion in the forest, and so extracting them would be difficult. This challenge heavily dissuades the government from providing aid. Colonial officials write that “there can be no justification . . . for asking the Department to work at a loss to provide raw material for an industry that so far as can be foreseen will never be able to afford to pay a commercial price for its raw material.” Officials seriously contemplate if Pillai’s application and request is worth their time, inquiring into the viability of Pillai’s business and the financial solvency of Chettiar, his main investor.

The application makes clear that Pillai is absolutely dependent on the government’s cooperation for the success of his business. When he hears that wood from the Cumbum Forest would not suffice, he decides to shift the site of the factory from a small hamlet to the much larger city of Madurai, which would have had easier access to railways and, thus, other reserved forest resources. The government is much more inclined to acquiesce at this point, claiming there were a variety of tree species from nearby forests that would be suitable and that they could provide 4,000 cubic feet of lumber per year at a highly subsidized rate. In essence, after nine months, Pillai’s request is finally approved, as are the applications of several other matchworks, a noteworthy success rate when the overall approval rate for state aid was less than 20%. This is perhaps indicative of a preference for chemical works as opposed to other kinds of industries for receiving government assistance.

Further correspondence with Pillai is missing from the historical record, but if his matchstick business ever became commercially viable, it likely shuttered within a few years, as most small businesses did at this time. Yet Pillai’s story is emblematic of a new culture of chemical entrepreneurs producing consumer goods for the Indian market. We can see that to start a match factory required not only chemical expertise, but also botanical knowledge of the appropriate trees for matchwood, knowledge of rail and transportation networks, and the subtle arts of negotiating with the government for special dispensation.

Despite these challenges, Indian industrialists and chemical professionals were eager to participate in the industrial economy. Many of the matches in Gautam Hemmady’s collection came from villages, such as Sivakasi, Sattur, and Virudhunagar, all of which are in the present-day Virudhunagar district, a hot and dry region of Tamil Nadu that is ideal for pyrotechnics production.

The region’s industrial origins can be traced to a pair of paternal cousins, Ayya and Shanmuga Nadar, who brought the knowledge and technology of matchstick production after apprenticing in factories in Calcutta. In 1923, they started their first matchworks in Sivakasi, importing machinery from Germany and training locals to operate it. Eventually many matchworks expanded into fireworks production because the two products require similar raw materials, including red phosphorus, potassium chlorate, and sulfur. The Nadar cousin brothers (a common term of Tamil kinship) are now revered, almost legendary, figures as Sivakasi and fireworks have become synonymous for Indians purchasing firecrackers for Diwali and other special occasions. The city now produces 90% of India’s firecrackers, although it frequently comes into the national spotlight for workplace safety hazards, rampant child labor abuses, and pollution.

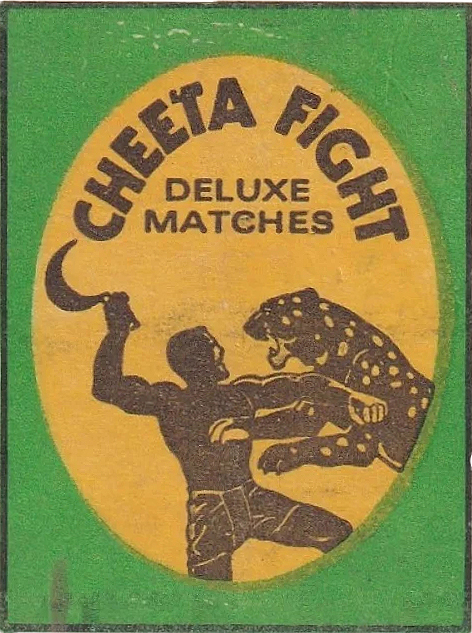

As these Indianized forms of chemical industry slowly came online, local imagery and iconography were deployed to turn a generic product into something uniquely Indian. Cheeta Fight matches, sold by WIMCO in the Tamil region of South India, drew on such a legend.

According to lore, one day a man named Chinna Reddy was patrolling his banana orchard in a village in Tiruvallur district when a wild cheetah attacked. With the help of his dog, Chinna Reddy slayed the cheetah with his sickle, and his story became mythic within a culture that celebrates masculine heroism, especially the violent kind. Thus, even a foreign-owned company such as WIMCO could see the value in attaching the story to its products. Chinna Reddy’s legend has remained iconic in the intervening years, becoming the subject of a novel by Tamil writer Tamilmagan. That cheetahs have since gone extinct from India only heightens the epic stakes.

As the British Empire declined toward the middle of the 20th century, the imagery of matchstick covers turned political, adopting imagery tied to the struggle for anticolonial justice. Symbols of Indian nationalism, including flags, portraits of freedom fighters, and patriotic rhetoric, encouraged Indians to use domestic goods (a movement known as swadeshi) and challenge the British authority. These images were ultimately more of a marketing strategy than a tool of resistance. After independence, matchstick manufacturers seamlessly pivoted to film stars and other celebrities for branding.

Agitation against European hegemony on the matchworks factory floor was far more substantive. In the early 1940s the WIMCO factory in Chennai’s Tiruvottiyur neighborhood (an area now known as Wimco Nagar) went on strike. The protest, led by a worker known simply as Ari, turned into a violent confrontation with the police, who sought to protect foreign business interests and quash the insurrection. While Ari was likely imprisoned and the strike quelled, this instance was part of a long line of industrial labor strikes (also known as hartals) that weakened colonial authority and emboldened the Indian masses.

Issues of Indian labor, industrial development, and anticolonial resistance are complex and voluminous, but have been condensed to fit inside a matchbook for the purposes of this essay. The larger point is that the history of the matchstick in India, or of any technology that traveled the world, is neither a riff on the European overture nor the same melody in a different key.

The colonial context is crucially different for how we understand chemical expertise, resources, materials, business culture, and their histories in South Asia. When we look at the larger arc of the 20th century, these histories are inseparable from politics, economics, and the struggle for freedom from colonial rule. Illuminated by a lucifer’s light, the history of the match is replete with meaning, going far beyond the difference between a fire-producing stick and a kindled romance.