Jill Biden brings an unprecedented distinction to the 46th U.S. presidency as the first FLOTUS with a doctorate. But almost a century ago, Lou Henry Hoover entered the White House not only as one of the first women in the United States with an undergraduate degree in geology but also as the first historian of science to reside at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Lou Henry met Herbert Hoover while the two were studying geology at Stanford in the 1890s. They married and moved abroad after Henry’s graduation. Herbert Hoover became a distinguished mining engineer, and Lou Henry Hoover, unable to find a position doing geological fieldwork, instead cultivated an interest in history to stay engaged in science and research. While living in London she began collecting historical works about geology, and from 1907 to 1912 she and her husband produced the first English translation of the classic Renaissance mineralogy treatise De re metallica. The Hoovers viewed this long-term project as a scientific collaboration, undertaking experimental chemical reconstructions to determine the precise meaning of phenomena described in the original Latin.

“Sometimes the task amounted more to scientific detective work than to translation,” Herbert Hoover later recalled.

While her husband was hailed as a “man of science” before, during, and after his presidency, Lou Henry Hoover’s scientific interests and accomplishments were rarely celebrated. Why did they undertake this scholarly project, and why did Herbert Hoover get all the credit?

Lou Henry was born in Waterloo, Iowa, to a middle-class family in 1874. During her teens her family migrated west, seeking greater financial opportunities and a milder climate. They settled in Whittier, California, close to Los Angeles, in the mid-1880s.

Henry had professional aspirations and attained a teaching degree from San José Normal School in 1893. During her time at San José, Henry and a group of friends founded the Agassiz Association, named for the renowned Swiss-born naturalist, with Henry as president. The purpose of the club was “to study botany, zoology, microscopy, and taxidermy, and to make additions to the school’s natural history collection,” by meeting weekly for discussion and collecting trips.

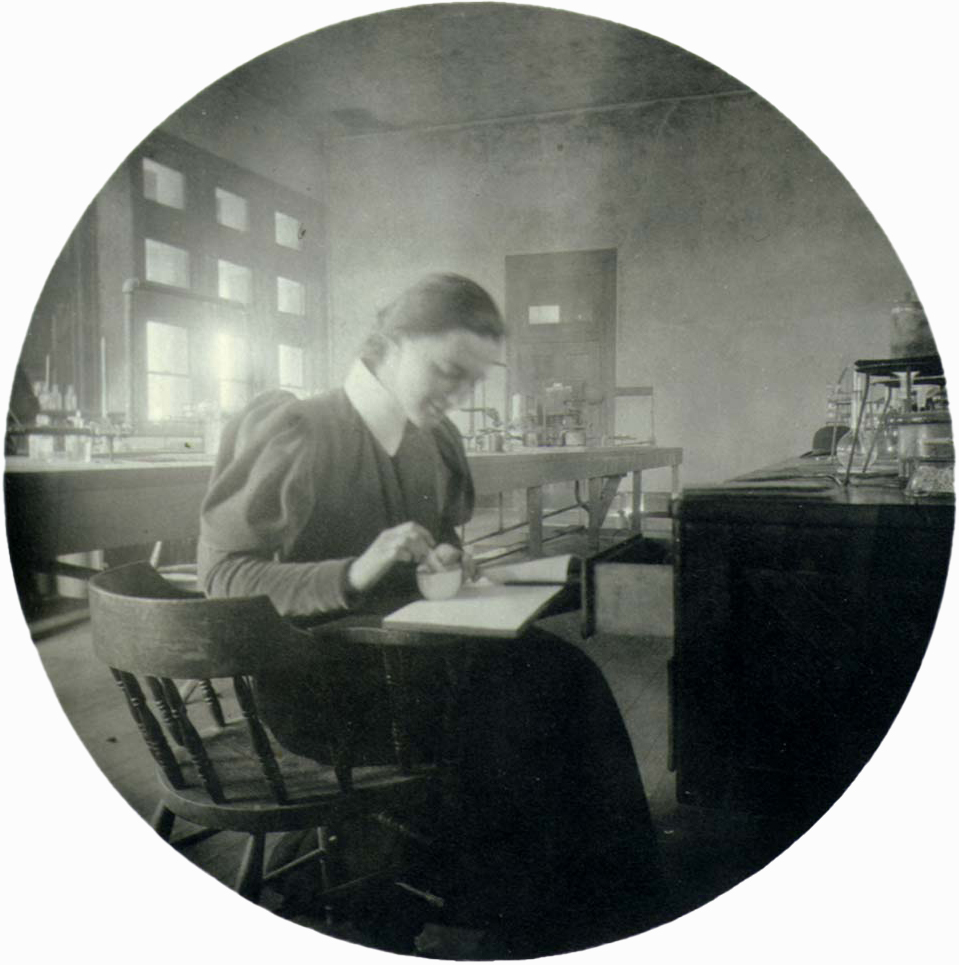

A public lecture by John Casper Branner in 1894 piqued the 20-year-old Henry’s interest in geology. Branner was on the faculty of a new coeducational university in Palo Alto and encouraged Henry to apply. She began her second bachelor’s degree that fall, joining Stanford University’s fourth class. While one quarter of Stanford’s early female graduates had been in the sciences, none had majored in geology before Henry, who received her BA in the subject in 1898.

After graduating, Lou Henry was unable to find a position as a field geologist and instead took the next best opportunity—she married Herbert Hoover and joined his fieldwork abroad. For the next 15 years Herbert Hoover’s work as a mining engineer took the couple on extensive travels to Europe, Asia, and Australia, until the outbreak of World War I.

As Herbert Hoover became internationally renowned and extremely wealthy from his mining concerns, Lou Henry, now Lou Henry Hoover, pursued her own interests in tandem. While raising two sons and managing the family’s affairs, she learned Mandarin and published a biographical article on British geologist John Milne. To the surprise of local mine operators, she often visited mines with her husband to collect specimens, which she sent back to John Branner at Stanford.

Branner’s laboratory was where Lou Henry Hoover first became acquainted with Georgius Agricola, in whose company the Hoovers would spend the formative years of their marriage. Agricola was born Georg Pawer, in 1494, in the German state of Saxony, a region rich in silver mines. He enthusiastically embraced the rise of Renaissance humanism, studying first Latin and Greek, and then medicine, in Leipzig, Paris, and Italy, perhaps at the famous University of Bologna.

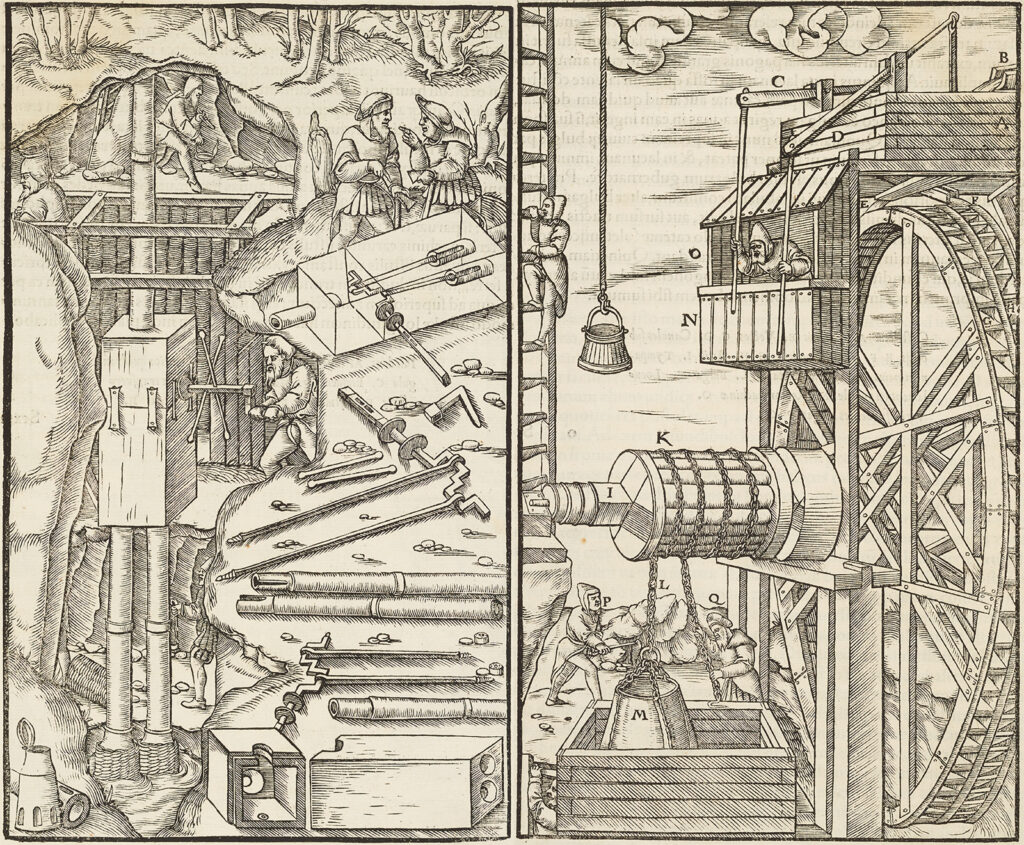

Medicine brought Agricola to the mining town of Joachimstal, in today’s Czech Republic, where he practiced as an apothecary and physician. He also began to publish studies of the region’s mining knowledge, comparing local German practices to those of ancient Latin and Greek authorities, focusing especially on mineral medicines. Agricola’s interest in minerals soon expanded beyond their healthful properties to their origins and to miners’ techniques for identifying and extracting their ores. Over several decades, Agricola produced a series of studies on theoretical and practical explorations of the subterranean world. This culminated in his magnum opus, De re metallica, published posthumously in 1556, a year after his death. Agricola’s treatise presented the earth as a kind of natural chemical laboratory in which minerals were formed; historians now consider it among the foundational texts in both the history of chemistry and geology in early modern Europe.

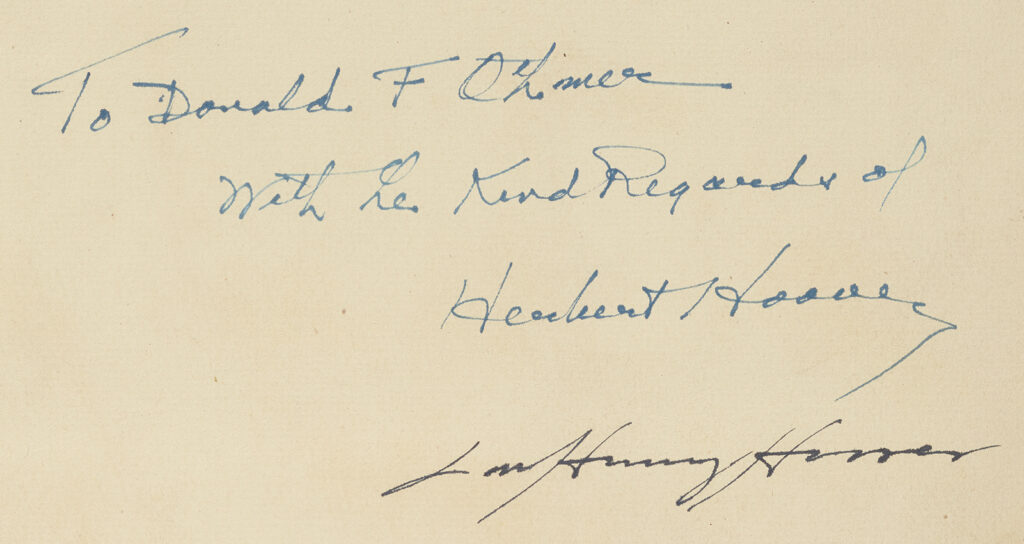

Despite its well-known status during the Renaissance—including a translation into Chinese in 1640—De re metallica had no English translation before the Hoovers’, in part because English did not become a major international scientific language until the 20th century. In his memoirs, Herbert Hoover presents the idea of an English translation as his own initiative, but in fact Lou Henry Hoover had first suggested the project after consulting a copy of Agricola’s treatise in the British Museum and locating an original for purchase. She had become acquainted with London’s thriving rare-book trade and, following her scientific interests, began to build a collection of important works in the history of European mineralogy, chemistry, and geology.

The Hoovers spent more than five years working on the translation and scholarly annotation of Agricola’s treatise. Lou Henry Hoover supervised a team of assistants, secretaries, and translators, while also collaborating with her husband on laboratory experiments and critical annotations to the text. When they encountered obscure language about metallurgical processes, the Hoovers turned to experimental investigations to determine what exactly Agricola had been describing, re-creating the chemical reactions involved in assaying and refining metals. These technical insights, coupled with extensive textual research, added significantly to the translation’s analysis of Agricola’s contemporary context and his place in the longer history of science.

The Hoovers followed in the steps of Agricola, who had sought to integrate older mining knowledge with the science of his day. Owen Hannaway, a historian of early modern chemistry, argued that Agricola was “a humanist first and foremost” and that his interest in writing about scientific knowledge should be understood as part of a project to restore ancient wisdom to the present. Hannaway suggested that Herbert Hoover was doing much the same thing by investing in scholarship that promoted Agricola and his studies of mining technologies to the status of elite science, in the process recasting his own mining career as a distinguished scientific undertaking. Yet Hannaway overlooked the fact that Lou Henry Hoover was also distinguishing herself as a woman of science.

The Hoovers’ efforts were widely recognized, and both received prizes, honorary degrees, and extensive press coverage for their translation. Herbert Hoover was elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1915.

Yet these accolades consistently emphasized Herbert Hoover’s contributions over Lou Henry Hoover’s. For example, the New York Times review of De re metallica observed, “It is a book that in its first English translation should be of peculiar interest to the American public because of what it tells of its translator, one Herbert Clark Hoover, A. B., and his associate, Lou Henry Hoover.” Given that Herbert Hoover admitted his own weakness in Latin and that German was the only course he failed in college, it is unclear how much he really could have contributed to the translation. Rather, his role was to lend the project his scientific credibility, despite the fact that he and his wife held identical degrees. Rarely did public accolades extend the mantle of science to Lou Henry Hoover. And while she at least received authorial credit, many of the research assistants who had helped them over the years did not.

The irony is that Lou Henry Hoover is unlike the many women whose scientific accomplishments have been ignored or forgotten—she was well known during her lifetime and has remained a prominent historical figure. But even in the public eye, she was rarely recognized as a participant in the scientific enterprise. She received several honorary degrees that routinely cited her work on De re metallica as a literary accomplishment. Even historians of science have mostly failed to recognize her lifelong engagement with geology.

Credited or not, her interest in Agricola was part of a life-long commitment to the earth sciences, which she pursued through activities considered more appropriate to her class and gender. After World War I she became a prominent leader in developing the national Girl Scouts program, working to provide young women access to both technical knowledge and the natural world. Today, the Girl Scouts is one of the few places where evidence of Lou Henry Hoover’s scientific commitments can be found—two badges for STEM activities are named after her.

In writing and reading about science’s past, we make judgments about who we think has participated and contributed to the scientific enterprise. The Hoovers worked to make Georgius Agricola into a scientist, in the process bolstering their own scientific credentials and interests. By extending the same consideration to Lou Henry Hoover, we can recognize her efforts to contribute to the gendered scientific culture of her time and the precedent she set in creating new forms of scientific education and participation.