Is fear a socially unifying emotion? During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic it certainly seemed that way. In the United States people hunkered down indoors, avoiding gatherings. Schools and businesses shut down, face masks were ubiquitous, and, for a brief moment, it seemed as if public health messaging had prevailed. But then something shifted—safety regulations became politicized.

For scholars and policymakers, the politicization of the disease and its management has underscored many of the difficulties inherent to public health messaging. And as future global climate and health crises loom, academic debates often center on the value of scare tactics—text and images that warn of an impending apocalypse. Opinions vary over the impact this kind of messaging has on the success of policies. Some experts claim that fear proves highly motivational and that there is no way to avoid prognostication of a dangerous future. Others argue that fear-based messaging can create a sense of widespread fatalism or even societal panic.

Either way, the COVID-19 pandemic provides a distinct historical moment in which concerns over the way scientific issues are publicly conveyed and addressed by the state have become paramount. In the United States, CDC guidelines on social distancing and masking have been carefully constructed to encourage public confidence and adherence.

Nevertheless, social, cultural, and political divisions have led to various claims that the state’s recommendations were overly cautious and possibly authoritarian, with the face mask (in its various forms) serving as the central object of disagreement. Beyond its practical value, the mask became a complicated symbol, one that could encompass broad concern for public health, a commitment to standing American political structures, and a reconciliation with a newly dangerous atmosphere.

For many of its detractors, the face mask was a symbol of new societal fears, overstated dangers of COVID-19, and an attempt to coercively bind the American people in the midst of an imagined crisis. These dissenters often presented themselves as the defenders of civil liberties, rejecting the heavy hand of the state to continue their vision of “the American way of life” and insisting that supposed scare tactics would have unanticipated and undesired effects on everything from long-term mental health to daily social cohesion.

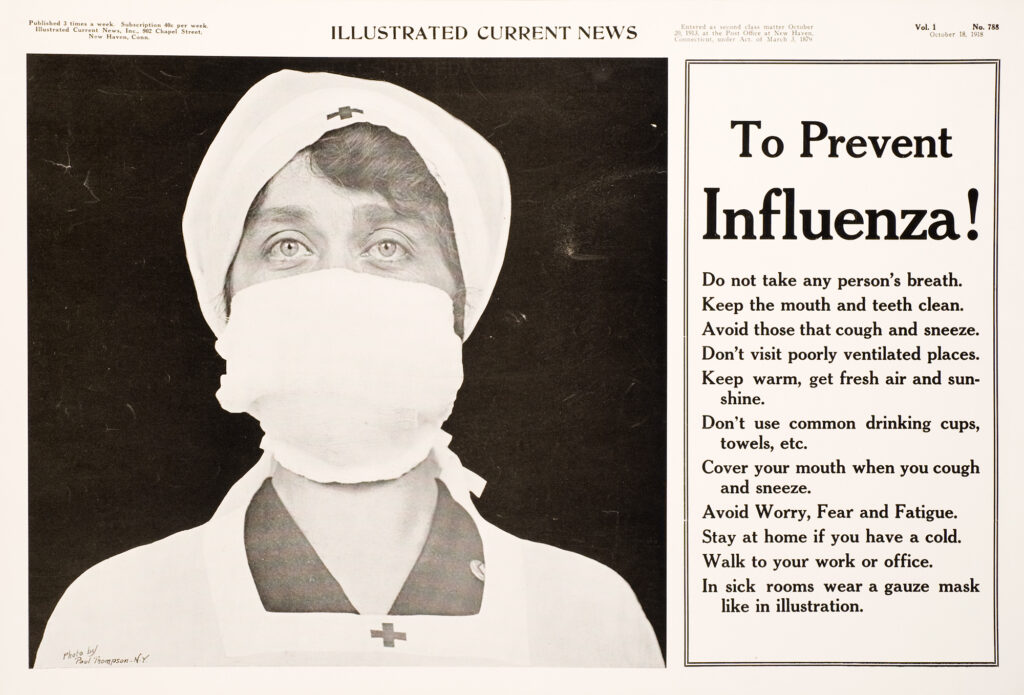

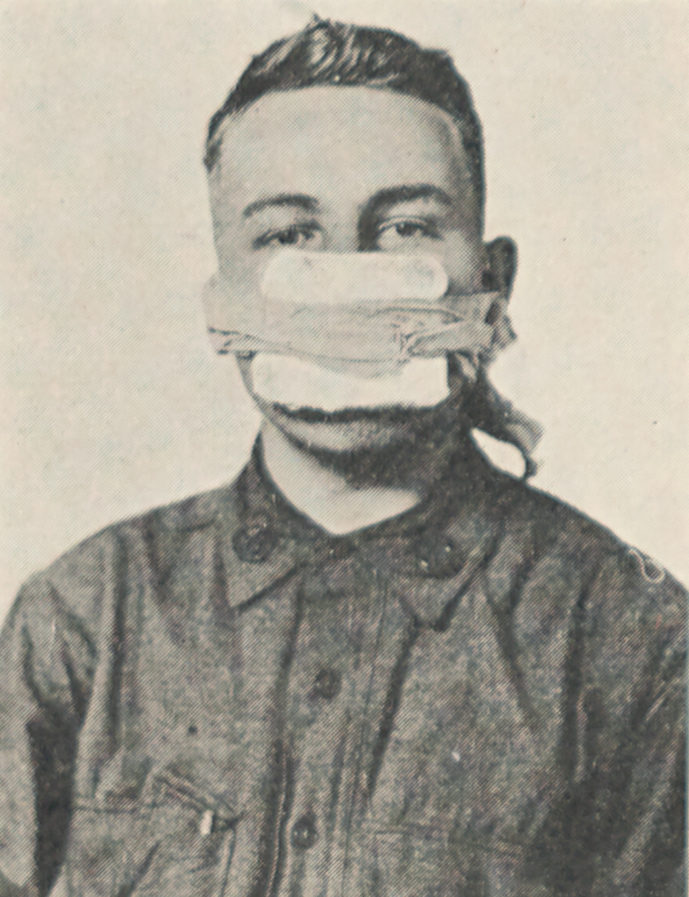

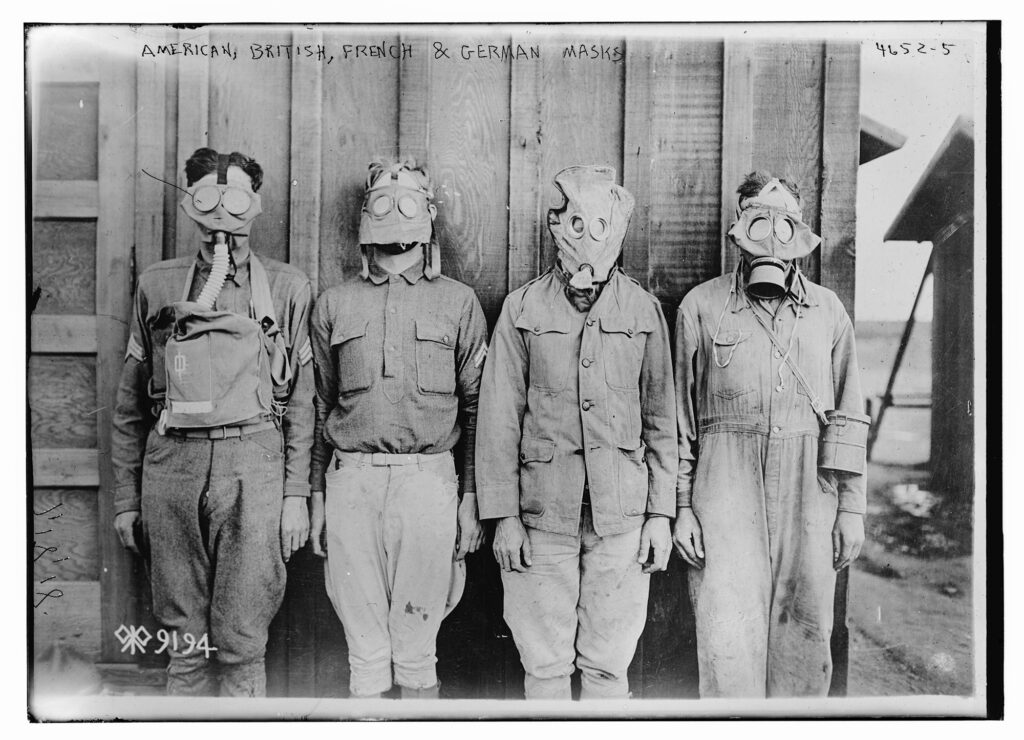

Dissenters rarely acknowledged, however, that the COVID-19 pandemic was not the first historical instance in which modern states tried to mask their populaces. In search of precedent, many Americans encountered images of the gauze masks worn during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–1920. However, these masks were rarely standardized, and they were required only for relatively brief periods of time in certain parts of the United States. But there was another attempt to mask populations in the early 20th century that was far more widespread and long-lasting: the provision of gas masks in the 1930s.

Like the surgical mask during both the Spanish flu and COVID-19 pandemics, the gas mask was seen as a protective device laden with meaning. Those who ultimately rejected the gas mask often made familiar claims about its symbolic role in anticipating and even expediting a dangerous future, stating that such a seemingly foreign and foreboding object militarized the public and made war unavoidable in the collective imagination.

This history, and the history of the artificial respirators that preceded the gas mask, thus resonates with contemporary deliberations over protective equipment. While technologies such as premodern respirators, gas masks, cloth face masks, and modern medical respirators maintain important technical differences and provide different types of protection, their symbolic associations and messaging has, at times, appeared quite similar.

A retrospective look at the development of these technologies and their fluctuating symbolism reveals the difficulties facing any state that wants to protect all of its citizens without producing fear or panic.

Respiration Technologies

Even in the ancient world, people used textiles and sea sponges to protect themselves from naturally occurring toxic fumes and chemical attacks from their enemies. The Greek historian Thucydides reported in his account of the Peloponnesian War that the Spartans attempted to weaken the defense of Plataea by choking the Athenian soldiers with smoke from a burning mixture of sulfur, pitch, and wood. Similar methods were used during premodern sieges, while medieval navies blinded enemy sailors with gas from heated quicklime (calcium oxide). The beleaguered sailors protected themselves with masks fashioned from simple textiles and animal bladders.

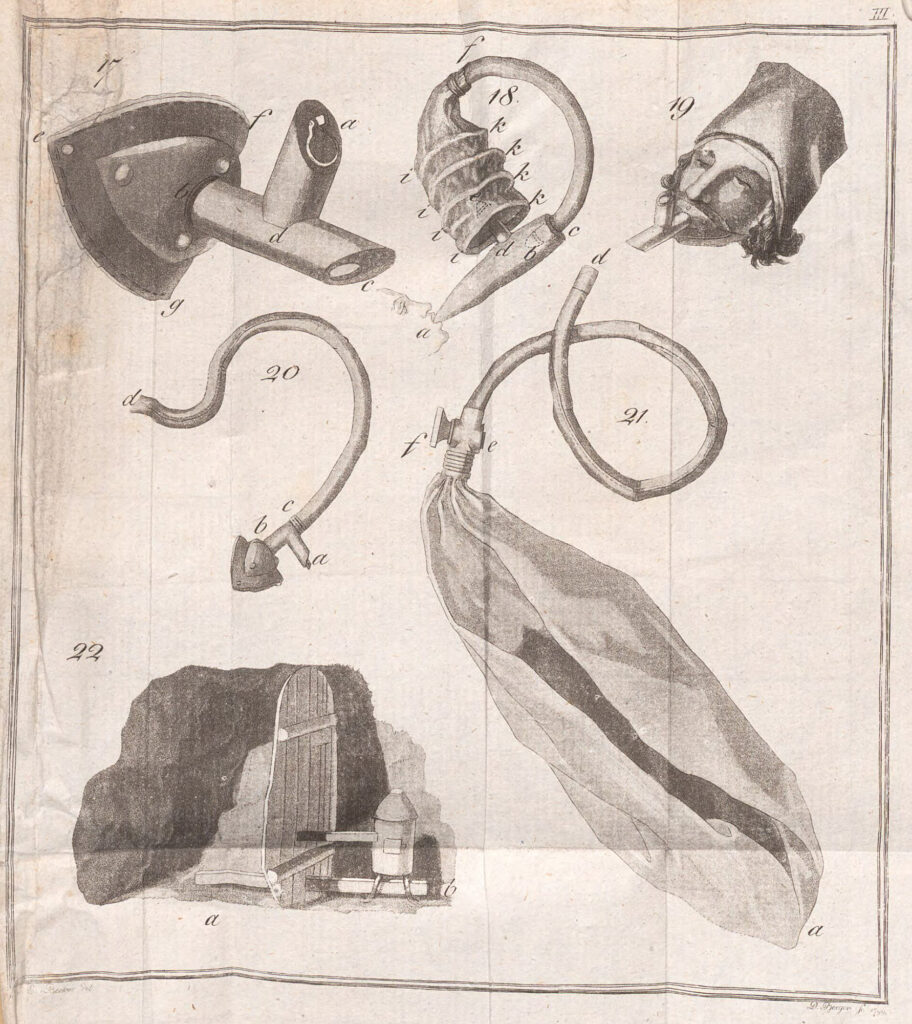

The first major technological advances in protective respiratory equipment were made not for war but for industry. In 1785 French scientist Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier produced the first functional air-providing respirator. Pilâtre de Rozier’s device was essentially a small mask attached to a long breathing tube that allowed the wearer to descend into poisoned wells or mines. The design was not widely adopted, but it sparked interest in a respirator that could be used in newly developing industrial fields.

In 1796 Alexander von Humboldt completed work on a Respirationsmaschine (or respiration machine) that could be used to rescue miners from arsenic leaks. Similar to Pilâtre de Rozier’s design, this respirator consisted of an inflatable bag connected by tubing to a small mouthpiece. Von Humboldt successfully pitched the respirator to the Prussian military as a way to protect engineers working underground with gun powder and other explosives.

Around the same time, respirators became important to the increasingly professionalized world of firefighting. According to a fanciful story, firefighters first began to use respirators in the early 1820s after Englishman John Deane entered a burning stable while wearing an antique knight’s helmet attached to an air hose. In 1823 John and his brother Charles patented this impromptu invention as the “smoke helmet.” In 1827 engineer Augustus Siebe produced the first standardized smoke helmets, constructed of copper and attached to an airtight leather or canvas suit resembling that of an underwater diving rig. A short tube protruded from the front of the helmet for exhalation, and a long rubber hose ran from the rear of the helmet to a bellows that provided fresh air. The design achieved little commercial success until it was repurposed for diving in 1828.

Until the mid-1800s all widely available artificial respirators employed hoses to supply fresh air. Thus, the wearer could never stray too far from the source of air, nor could they move without restriction. European and U.S. mining companies increasingly desired a mobile respirator for their workers. In 1847 American inventor Lewis Haslett created the Inhaler or Lung Protector to filter mining dust from the air. Haslett’s device featured a mouthpiece with two valves, one for inhalation through moistened wool and one for exhalation. The compact simplicity of Haslett’s filter design allowed the wearer to walk about freely, and in 1849, Haslett received the first U.S. patent for a mobile, air-purifying breathing device. For this reason, the Haslett Inhaler is often considered the progenitor of the modern gas mask.

In the decades that followed, inventors replicated or enhanced aspects of Haslett’s design. This explosion of respiratory technology was partly driven by expanding industrial work in hazardous conditions, but also by complicated and tenuous patent laws across European nations.

In 1854 Scottish chemist John Stenhouse incorporated a filter with powdered wood charcoal between two sheets of wired gauze. In 1871, Irish physicist John Tyndall replicated Stenhouse’s design and added lime and glycerin to the charcoal filter. British inventor Samuel Barton’s 1874 respirator added a rubber and metal face shield, glass eyepieces, and a rubber-coated hood. The search for increasingly effective chemical filters would continue over the next three decades alongside the corollary demand for greater facial protection.

By 1900 mobile respirators were largely successful in combatting the kinds of toxic fumes that European and American scientists, engineers, miners, and firefighters regularly encountered. But as technological developments and capital investment allowed the mining, diving, and chemical industries to grow, respirators were used in progressively deadly scenarios. Industrial workers and chemists increasingly donned respirators to work with deadly gases, such as arsenic and sulfur, in deep mines, cold waters, industrial tanks, and other hazardous places. Thus, these devices required a substantial level of technological trust from a wearer who could not afford any malfunctions. At the dawn of the 20th century, the steady development of the respirator appeared to most contemporaries as part and parcel of greater European technological progress. It was a safety device and a tool of scientific endeavor, one that would protect human life while conquering previously inhospitable worlds.

Risk and Danger

While rough sketches and prototypes existed at the turn of the 20th century, artificial respiration was substantially developed after April 22, 1915, when German chemist Fritz Haber unveiled his secret plan to win World War I.

After months of research and testing, Haber directed the first large-scale chemical attack in modern history, coordinating engineers who synchronously released chlorine gas from 5,730 entrenched cylinders along a 7,000-meter front in Ypres, Belgium. A 150-ton white cloud of chlorine rose from the German trenches and wafted toward French colonial soldiers. After some soldiers fell gasping to the ground, the French troops broke ranks and fled. Reports of the German chlorine attack reached British high command within hours. The so-called chemist’s war had begun.

Caricature of Fritz Haber releasing gas onto a World War I battlefield, signed by E. Schlumberger, undated.

While Haber and the German commanders celebrated this technological victory in the following days, the chlorine attack at Ypres proved strategically indecisive—German troops refused to advance anywhere near their own toxic clouds. Only Haber’s hand-selected engineers were outfitted breathing apparatuses for protection.

To protect their troops, British and German commanders alike began distributing cotton mouth pads and chlorine-retarding bicarbonate solution. Soldiers were instructed to douse their mouth pads with the retarding chemicals once they recognized the presence of toxic gas. If they ran out of these solutions, they were told to urinate on a handkerchief and put it to their face. These tactics worked quite well against early chemical weapons, and Allied troops at Ypres eventually repelled German advances.

In the weeks that followed, cotton mouth pads were replaced by particle-filtering masks, and armies began to distribute goggles to prevent eye injuries. Protection against chemical weapons started to receive significant attention and research funding.

The Germans remained the major innovators, placing all protection concerns under Haber’s larger chemical weapons program. Haber was ahead of the curve, having established a central research site for this work within the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry near Berlin. In the summer of 1915 the lab began working on a mobile respirator that would neutralize chlorine gas.

The most important part of this new breathing device was the filter, which would provide the portability necessary for trench warfare. Haber’s lab produced several prototypes of this filter before organic chemist Richard Willstätter and his assistants joined the project.

Willstätter had made his name by studying the structure of plant pigments, including chlorophyll, at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. In 1912 the gregarious Haber lured Willstätter to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, located near Haber’s own research institute. This physical proximity naturally would have drawn Willstätter into the German military efforts if not for a major catch. Willstätter was an avowed pacifist who refused to publicly support Germany’s war aims, let alone engage in chemical weapons research. But after considerable cajoling from his good friend Haber, Willstätter agreed to work on chemical weapons protection research, which he posited as a humanitarian endeavor. While Haber’s other gifted scientists produced poisons to kill thousands, Willstätter saw himself as the chemist who could prevent such an outcome.

Over the span of five weeks in the summer of 1915, Willstätter and his team developed the “three-layer cartridge.” This new respirator filter incorporated layers of diatomite, granulated active charcoal, and pumice or diatomaceous earth saturated with hexamethylenetetramine or piperazine.

After extensive testing, Willstätter’s filter was deemed a success. It was paired with a rubberized face mask to produce the Linienmaske, or line mask, named after the airtight seal the mask attempted to create with the lines of a soldier’s face. The Linienmaske served as a blueprint for the millions of subsequent German gas masks produced during the war.

Unfortunately for Willstätter, the success of the Linienmaske had unintended and possibly unforeseen consequences. It encouraged the Allies to develop their own gas masks as well as new chemical weapons that could circumvent Willstätter’s filter. The Germans similarly attempted to develop new toxic gases. By the end of the war, the sides were barraging one another with millions of shells holding mustard gas and arsenic-based compounds. Gas mask technology, on the other hand, plateaued around 1917. This was particularly devastating for the Germans, who lacked the leather, rubber, and workforce to provide effective gas masks in the final years of the war.

No wonder few of the men who wore Willstätter’s gas masks (and the variations that followed) viewed them as lifesaving devices. Conceptually tied to the chemical weapons that insidiously attacked soldiers’ skin, eyes, and lungs, the gas mask was often seen as a harbinger of the technological violence that broke millions of bodies and minds. This interpretation of the mask is explicit in the cultural production that came out of the war, notably in the German painter Otto Dix’s Storm Troopers Advancing Under a Gas Attack.

The gas masks in Dix’s engraving conceal and distort the wearers’ faces. The masks appear permanently fixed to the soldiers’ heads, morphing them into violent cyborgs as they charge toward the viewer. Clearly for Dix and many other postwar contemporaries, the chemical technologies of World War I, whether initially intended for aggression or protection, were part of a larger nightmare of futuristic violence that had already arrived for the modern soldier.

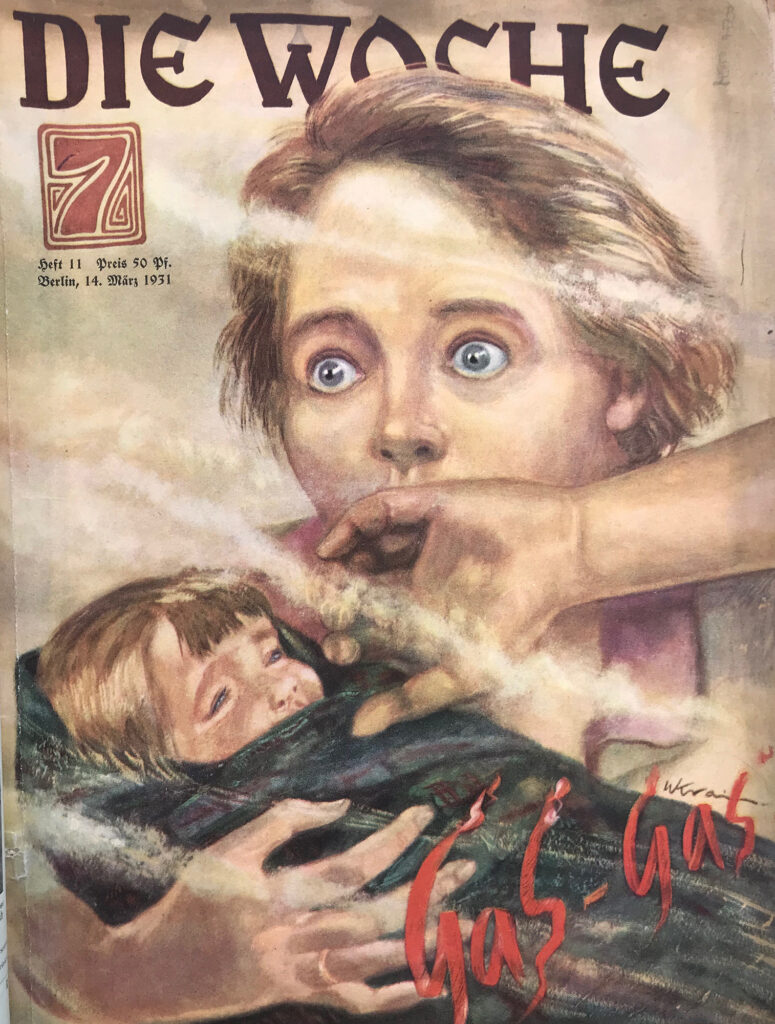

Such interpretations would gain further expression throughout the interwar period when poison gas was inextricably tied to the collective fear of aerial bombings and the anticipation of another world war.

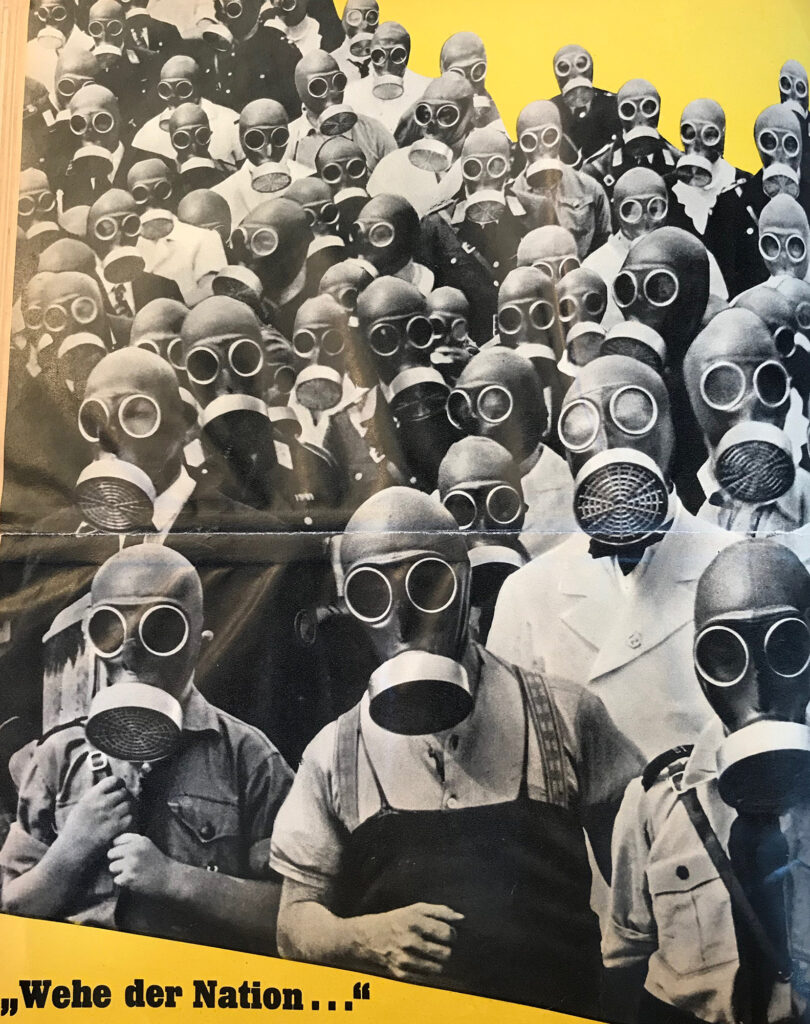

Novelists, artists, philosophers, military commanders, and technical specialists in the 1920s and 1930s saw the gas mask as a potent symbol of impending danger and violence. Visions of Europeans struggling over precious gas masks as they bombed and gassed each other to extinction proliferated. As nations prepared their populations for an aerial war they were certain would soon arrive, the gas mask became an uncomfortable yet necessary survival tool for soldier and civilian alike.

Chemist Gertrud Woker was just one pacifist troubled by the gas mask’s symbolic power, arguing in the late 1920s that it was part and parcel of broader attempts to militarize European nations. Indeed, by offering a tentative sense of protection from poison gas, the gas mask encouraged citizen gratitude to a bellicose state and its armament industries. In its daily presence, the mask reminded Europeans that a chemical war was coming; an apocalyptic future was practically baked into its rubber and celluloid construction.

In the mid- to late 1930s, European states finally realized their long-standing desires to distribute gas masks to their citizens. Under the Nazi regime, Germans were required to buy a Volksgasmaske, or people’s gas mask; the French offered their own national gas mask at reduced cost. The British distributed several free gas mask models to civilians, including a colorful “Mickey Mouse” mask that attempted to normalize the device for children. Even the United States delivered 500,000 masks to Hawaiian residents in anticipation of a Japanese chemical attack.

In the Hawaiian case, American experts debated whether standard gas masks would fit the physiognomy of the island’s Asian population. The British were similarly concerned about fitting and delivery to their colonial subjects. The fact that gas masks were not ultimately provided for entire colonial populations revealed both the limits of national belonging as well as the belief that the threat of chemical warfare was most pressing in Europe. This was most clearly demonstrated in Nazi Germany, where preparations for chemical warfare intruded on daily life except for Jews and other “undesired” populations who were never provided with gas masks or any other form of protection. Indeed, in an illustrative scene from the summer of 1942, a Jewish man reportedly asked a German official where he could procure a gas mask. The official responded, “Gas masks are surely pointless for Jews.”

While it was surely better to have a gas mask than to be left unprotected, interwar diary entries captured the public’s fear and hatred of the mask. In the words of one young German girl,

A British contemporary similarly noted, “Although I could breathe in [the gas mask], I felt as if I couldn’t. . . . The covering over my face, the cloudy [lenses] in front of my eyes, and the overpowering smell of rubber, made me feel slightly panicky.”

Clockwise, from top left, A mother fits a mask on her son during war preparation drill in Portsmouth, England. Cover for the story “The Gas Mask: The Symbol of Fate for Both the Army and the Homeland,” in the Nazi-affiliated magazine Die Sirene (The Siren), July 1938. A Young Pioneers defensive drill in Leningrad, Soviet Union, 1937, photograph by Viktor Bulla.

Associated Press; courtesy Peter Thompson; Wikimedia Commons

The construction of the gas mask presented its wearer with unpleasant physical challenges. But as the German girl makes clear, these technical difficulties were wrapped up in the imagination and expectation of even more terrifying destruction.

Interestingly, mass aerial gassing was not yet technologically possible in the interwar period. Nevertheless, the growing presence of the gas mask strongly suggested to Europeans that their world could end at any moment in a cloud of smoke and gas. The emotional seesaw between feelings of salvation and revulsion that defined interwar relationships to the gas mask would prefigure most reactions to the device through the Cold War and up to today.

Similar Fears, New Messaging

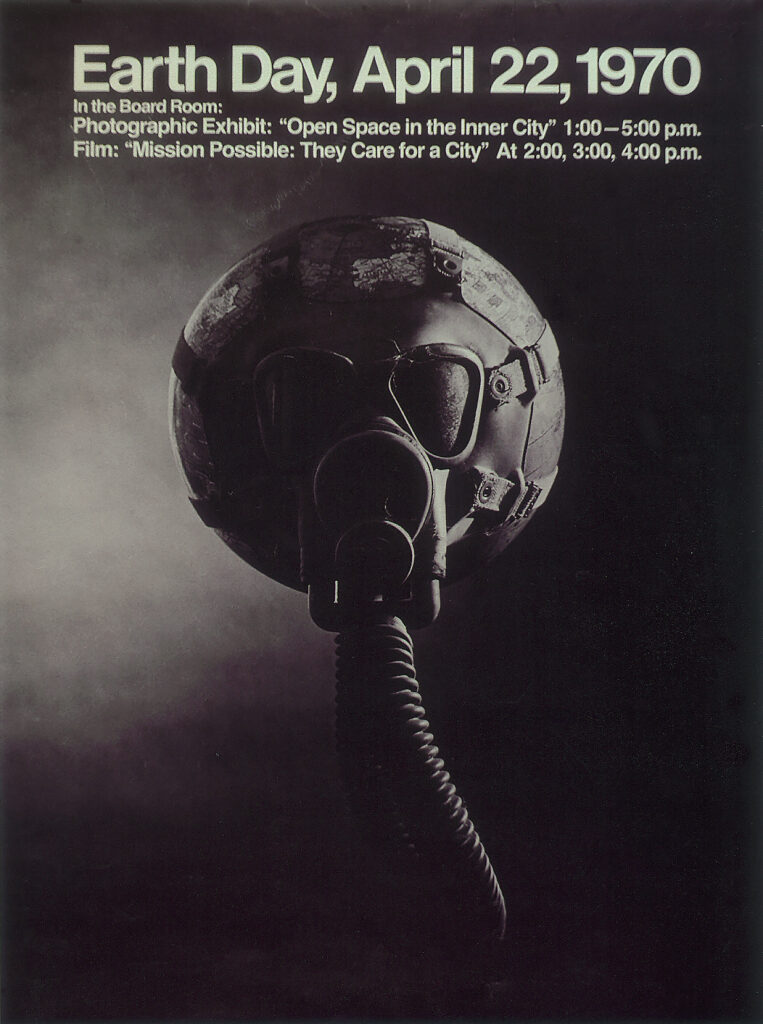

Despite its pre-history and the intentions of its creators, the gas mask remains, on the whole, a cultural representation of humanity’s inability to technologically control and pacify its increasingly militarized environment. But its intended political message has been repeatedly recast in different social, cultural, and political moments. The historian Finis Dunaway has made this point in Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images.

While the gas mask represented the horrors of total war for people between the world wars, Dunaway details the ways in which it was used to raise environmental consciousness in the United States in the years that followed. In particular, the mask was worn during the worst incidences of Los Angeles smog and on the first Earth Days to convey the fragility of both the natural environment and the human body. In this way the gas mask’s association with doom and destruction remained, but the desired political message was one of potential change rather than historical inevitability. Connections to warfare still lingered, but the gas mask could serve as a call to avoid one possible apocalyptic future.

Dunaway points out, however, that even this style of messaging runs the risk of becoming sensationalized and toothless while simultaneously failing to draw attention to unequal access to both healthy environments and protective technologies. Indeed, in an environmentally unstable future, access to technologies may determine the boundaries of protection, much as it did during the interwar period.

Of course, there are important technical and historical differences that set surgical masks and gas masks apart, and care must be taken in drawing conclusions or speculating about how our historical interpretation of this technology will carry into the future. Nevertheless, the history of the gas mask reveals the tightrope experts and authorities must walk as they prepare for future climate crises and pandemics. Wearable technologies, such as masks and other respirators, can protect both individuals and communities against a dangerous atmosphere. But at the same time, their existence doesn’t guarantee equal access to this protection. And by invoking the dangers they are meant to dispel, they may stoke fear and panic that undermines their intentions.