As his plane circled the recently liberated Dachau concentration camp, Leo Alexander could see the former inmates cheering and waving below. American planes often brought corned beef, potato salad, and other goods to feed the still-ailing inmates, as well as nurses and doctors to tend to them.

But Dr. Alexander had not come to heal anyone. Quite the opposite. He was there to tear the scab off a Nazi cover-up and expose some of the worst atrocities of World War II—horrific medical experiments on concentration-camp prisoners.

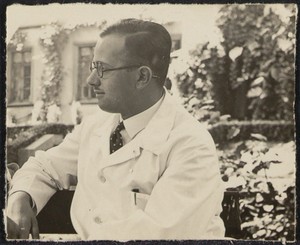

By May 1945 the Allies had heard plenty of rumors about such research—deliberately infecting prisoners with diseases, for instance, or submerging them in freezing water. But no one had confirmed anything or determined who might be responsible. That task fell to Alexander—a chubby, balding, bespectacled U.S. Army psychiatrist who’d been expelled from Nazi Germany a dozen years earlier.

The army gave Alexander just six weeks to do his job, from mid-May through the end of June, and he was working almost entirely alone. In many ways it was a no-win assignment. If he failed, crimes unprecedented in their scope might remain hidden forever and their perpetrators go unpunished. If he succeeded, he and the rest of the world would have to face the cruelties one human being can visit upon another—cruelties committed by a nation that saw itself as the most advanced civilization on Earth. Either way, as his plane passed Dachau and descended toward Munich, a short distance away, he knew the evidence he needed was somewhere on the ground below.

After a few fruitless days at Dachau, Alexander opened his investigation by interviewing Nazi scientists near Munich who had been involved in hypothermia research. The Germans had lost thousands of pilots and sailors in the cold seas of the North Atlantic during the war. So to study hypothermia and to test new methods of reviving hypothermia victims, military researchers had reportedly submerged inmates at Dachau in ice water and chilled them nearly to death.

But when Alexander tried to pin the scientists down, they proved evasive. They talked about submerging guinea pigs in ice water and prattled on about all they had learned from the work. They also bragged about their miraculous success in resurrecting troops rescued at sea. But how had they made the leap from reviving rodents to reviving people? Every time Alexander asked about experiments on humans, the Germans swore they didn’t know of any.

One scientist, however, did concede to running experiments on large animals. This revelation piqued Alexander’s interest: he had recently seen a strange watercolor painting in a nearby medical institute that showed equipment for submerging pigs in ice water. (Given their size and lack of fur, pigs are good models for humans in such work.) But if you could submerge pigs, you could also submerge human beings. Alexander insisted on seeing this equipment himself.

Impossible, said the scientist.

Alexander asked why.

It’s at another institute, quite far away.

How far? Alexander pressed.

Six miles.

That’s not too far by jeep, Alexander said. We’re going.

When they arrived, two German scientists showed Alexander more equipment for submerging guinea pigs—and immediately regaled him with additional details about this research. Irritated, Alexander finally cut them off. Where was the pig equipment? After more hemming and hawing the Germans led him outside and showed him two cracked wooden tubs behind a stable. This was all that remained, they said. To Alexander the contrast was telling. The small-animal equipment had been meticulously preserved while the large-animal equipment had been destroyed.

This and other clues reinforced his suspicion that the scientists were hiding something. But with no hard evidence he had to be cagey. To avoid spooking the Germans, who might destroy more evidence, he pretended to be satisfied with their answers and backed off.

Then having exhausted his leads around Munich, he began making his way hundreds of miles north to conduct more interviews in the town of Göttingen. It was nearly mid-June. He had just a few weeks left and had picked up nothing so far but a bad feeling.

Given Alexander’s bittersweet memories of Germany, his journey north through the bombed-out Reich must have been a melancholy one.

Alexander was born in Vienna in 1905 to a well-to-do Jewish family and enjoyed an idyllic childhood. Peacocks strutted around the lawn of the family mansion, where Sigmund Freud and Gustav Mahler were regular guests. Alexander followed his father into medicine and won prestigious posts in Berlin and Frankfurt, where he was taken under the wing of Karl Kleist, a brain pathologist and one of Germany’s leading doctors.

Then it all came crashing down. First, in 1932, his father was murdered in the street by a former mental patient, a random and senseless act; his mother died of an illness six months later. Next, in early 1933 the Nazi party seized power in Germany and quickly purged most Jews from civil-service posts, including many doctors.

Alexander was on sabbatical studying mental illness in China when the purge took place, so at first he didn’t realize—or didn’t want to realize—how bleak things were. In letters from that time he mentions how much he was looking forward to returning. Finally, his mentor was blunt: resuming his life in Germany, Kleist wrote, was “totally impossible. . . . Have no false hopes.”

Dispirited and suddenly stateless, Alexander sailed to the United States to start over. He settled near Boston and began working in a psychiatric ward. He soon became a U.S. citizen and started a family, and by the late 1930s he was teaching neurology at Harvard Medical School.

When the United States entered World War II, Alexander joined the army and traveled to England to treat soldiers for shell shock. After the Germans surrendered he expected to return to Massachusetts—until he was plucked out of the ranks by Allied officials. Given his background and familiarity with Germany, he was considered the perfect person to expose Nazi medical atrocities.

After weeks of searching, Alexander’s inquiry had stalled. And if not for a few chance remarks—and his persistence in pursuing them—the rest of his investigation might have faltered, too.

The first lucky break occurred on the road to Göttingen, when Alexander stopped at a military base for dinner. Inside the officers’ mess he happened to sit next to an army chaplain who had recently heard an Allied radio broadcast about medical experiments at Dachau and was curious to get Alexander’s opinion on them. As Alexander recalled, the chaplain “had been particularly horrified by experiments in which prisoners were placed in tubs of ice water while their sufferings and death throes . . . were recorded.”

Alexander was no doubt stunned. The way the chaplain described the experiments, they sounded eerily similar to the German experiments on “large animals.” But Alexander needed something firmer—like the identity of the doctor in charge of the Dachau research.

Did the broadcast mention any names? Alexander asked.

Yes, the chaplain said. One.

Who?

I don’t remember, the chaplain admitted.

Another dead end, but it was something. And when Alexander arrived in Göttingen, he had some leverage on the scientists there. I know about the Dachau broadcast. Who was experimenting on people there? When pressed, the scientists were quick to point the finger elsewhere, and in their deflections one name kept popping up: Sigmund Rascher.

Rascher was an air force doctor and a nasty piece of work—cruel, vain, unremorseful. In one interview Alexander heard about Rascher taunting another researcher at a conference, perhaps while drunk: “You have just published a book entitled Human Physiology,” Rascher said, “but all you ever did was work on guinea pigs and mice. I am the only one in this whole crowd who . . . knows human physiology, because I experiment on humans.”

Everyone in Göttingen agreed that Rascher was the man Alexander was after, an isolated sicko who had conducted experiments no one else would even consider. But if Alexander thought this story seemed too tidy—a single rogue scientist who was conveniently missing—he didn’t show it. Rascher was a lead, the first real lead Alexander had. And a tiny clue about him soon broke things wide open.

One interviewee let slip that Rascher had also performed experiments for the SS, the Nazi security agency. Now this probably seemed like small beer—bureaucratic minutiae. But the very next day Alexander learned that the Allies had just unearthed in a cave in Austria the secret archives of Heinrich Himmler, longtime head of the SS. Determined to hunt down every lead, Alexander made another long journey in mid-June to the Army Document Center near Heidelberg, which had assumed control of the archives.

It was a bonanza. Himmler was a packrat, obsessively preserving every scrap of paper that passed through his hands, and he’d annotated many of these documents with his signature green pencil. It took some digging, but around June 18 Alexander finally broke the seal on a packet blandly named “Case No. 707.” These papers would lead him down a path he would later compare to a dark German fairy tale, a land where “it sometimes seems as if the Nazis had taken special pains in making practically every nightmare come true.”

The archives confirmed that Rascher was every bit as nasty as his colleagues claimed. He had long wanted to experiment on human beings, but air force officials wouldn’t let him. So Rascher turned to the SS. His wife, Nini, was a former SS secretary and had close ties to Himmler—so much so that it was rumored Himmler had fathered the Raschers’ first child. Rascher nevertheless exploited his connection to Himmler to win permission for his research. And amid Himmler’s papers Alexander finally found proof that Rascher had performed hypothermia experiments on dozens if not hundreds of male concentration-camp inmates.

But the archives also confirmed Alexander’s suspicions that Rascher had not acted alone. The doctor had assistants and colleagues, collaborators and coauthors, all of whom helped run his experiments. Even Rascher’s wife took part, snapping autopsy photos of the victims’ hearts and lungs to document physiological changes.

(In retrospect the interviews in which the Germans blamed Rascher alone for the research sound suspiciously choreographed. The Germans could hardly deny that atrocities had taken place, but they apparently decided to heap the responsibility onto a single scapegoat to spare their colleagues—and themselves.)

Armed at last with hard evidence—and running out of time—Alexander hurried to confront some of the scientists who had lied to him. In Munich he also tracked down former Dachau inmates, who gave him more clues about what to look for in Himmler’s archives. Based on this information Alexander raced back to the document center to dig further. He put in hundreds of miles shuttling back and forth those last few weeks, piecing together what had happened inside the camp.

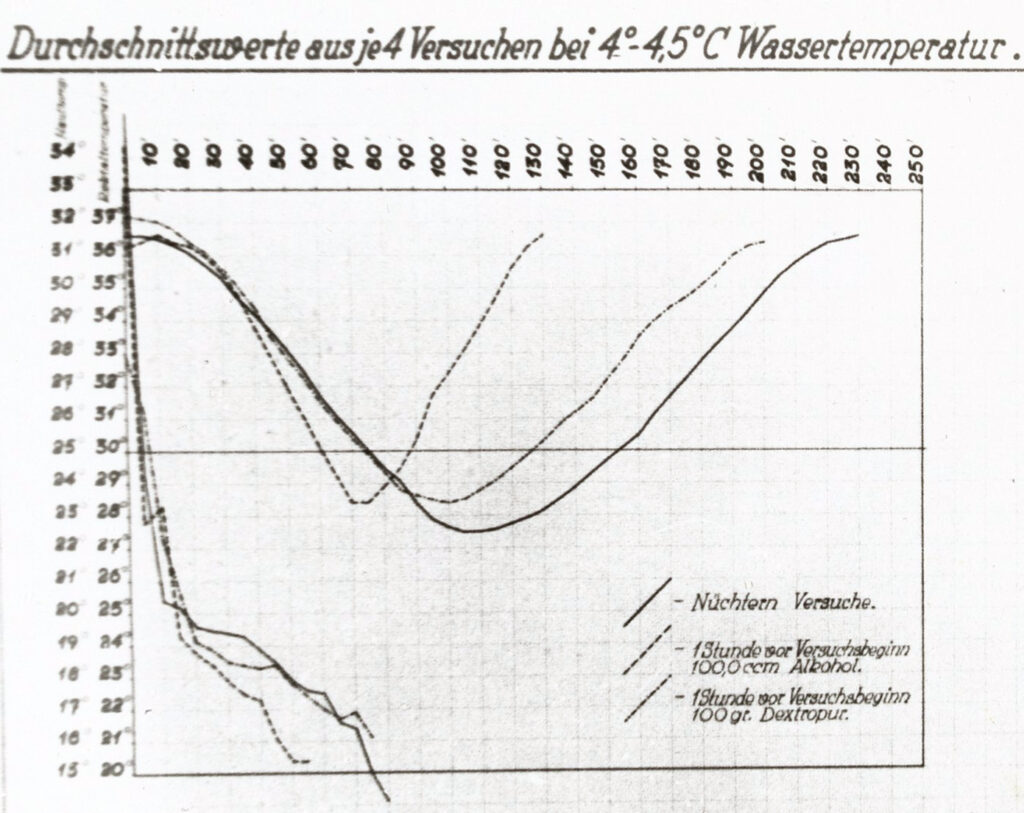

It was a ghastly picture. The hypothermia work began in Dachau in August 1942 at the now-notorious Cell Block 5. Day after day Rascher and his crew would immerse the “human material” in six-by-six-foot basins of ice water chilled as low as 36°F. A few (relatively) lucky prisoners were clad in protective underclothing treated with a special chemical—a “wood-cellulose fiber impregnated with peroxide”—that reacted with seawater to produce an insulating foam. It was reportedly quite good at preserving warmth. Most prisoners, however, wore plain, untreated military uniforms that offered little protection. Humiliatingly, a few prisoners were immersed naked.

The ice water relentlessly wicked away the men’s body heat. As it did so, Rascher catalogued their decline in nauseating detail, using results from rectal thermometers, spinal taps, and blood and urine samples. He tried taking their pulse and blood pressure, too, but the men were usually too stiff and shivering too violently to get a reading.

As their body temperature sank degree by agonizing degree, Rascher charted how their blood thickened, their spinal pressure increased, and their hearts slowed down. Some people foamed at the mouth, and their faces turned a “cyanotic” blue.

As a psychiatrist Alexander took special note of how the inmates had been broken mentally. Most hopped into the vats without any protest, even when naked; one witness marveled at their “marionette-like behavior.” After submersion, however, their sense of indifference vanished. Rascher complained about how they would “bellow” like animals; some begged to be shot.

When the victims’ core temperatures dropped to around 88°F—10 degrees below normal—their pupils would dilate, and they would lose consciousness. Death occurred at around 77°F. Alexander deemed one chart in the archives, which plotted the time to death in a subset of patients, “the briefest and most laconic confession of 7 murders in existence.”

Not everyone died in the ice baths, though. Sometimes Rascher would pluck a victim out and attempt to revive him. Different rewarming methods included hot-water baths, heated blankets, schnapps, vigorous massages, light-bulb cradles (tanning beds, essentially), and drugs that induced seizures. A few bewildered fellows were even dropped into bed with a pair of prostitutes. Despite these efforts many men were too far gone to save. Their core temperatures continued to sink even outside the water until they eventually succumbed. No one knows how many victims died from this group of experiments, but estimates range as high as 90 people.

Nor were these the only atrocities. Alexander discovered that Rascher and his colleagues had exposed prisoners to fatally low air pressures to simulate cockpit conditions at high altitude. Rascher also ran tests on potential blood coagulators, and whenever he needed a fresh vial, he’d simply shoot someone in the abdomen. Other doctors forced Dachau prisoners to chug salt water for days, or exposed them to nerve gas, or gashed their legs open and ground wood fragments and glass and bacteria into the wounds to simulate battlefield injuries. Still other doctors managed widespread sterilization programs to prevent the “unfit” from breeding. Far from acting alone, Alexander found, Rascher was immersed in a web of vile medical research.

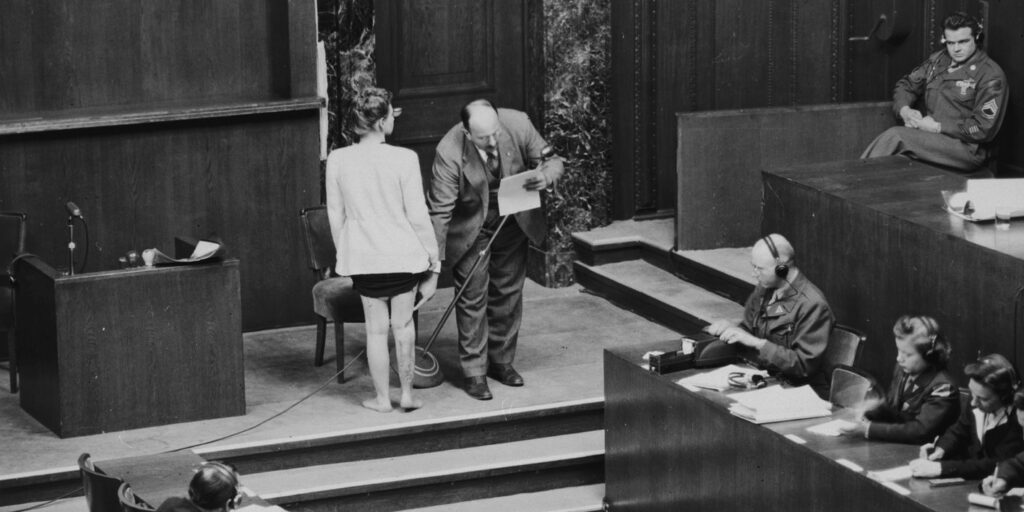

At the end of June, Alexander was summoned back to London to deliver his findings. By July 10 he had banged out a 228-page report on Rascher and the hypothermia research. He eventually churned out 1,500 pages of reports to help American lawyers prosecute war crimes at the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial in 1946 and 1947. The case seemed straightforward: German doctors had done unspeakably heinous things and deserved punishment. Stunningly, however, most of Alexander’s efforts came to naught.

Some high-level German doctors were convicted. But despite Alexander’s reports two of the doctors he exposed were acquitted at Nuremberg, and others never faced trial at all. The defense pointed out that no international laws or codes of conduct governed scientific research during the war. What’s more, the experiments were fully legal under German law. (Unlike monkeys, dogs, and horses, Jews and prisoners under the Third Reich enjoyed zero legal protection when it came to medical research.) The scientists argued that the prisoners were scheduled to die anyway, by gassing or another means. So according to their warped logic, the scientists had a free pass to experiment on such people since the outcome—death—was the same either way.

Worse still, some Nazi doctors who supervised experiments on inmates were invited to the United States and handed plum research contracts through a secret military recruitment program called Operation Paperclip. The reason was simple if cynical: American officials valued the doctors’ expertise for assistance in the looming Cold War with the Soviets and were therefore willing to ignore their grisly past.

One of the few doctors who did face justice was Sigmund Rascher, albeit in a twisted way. As Alexander learned in his research, Rascher and his wife were executed by Heinrich Himmler for three reasons.

First, they were caught trying to scam Himmler. After Nini Rascher suffered a miscarriage in the early 1940s, she feared she would be branded “biologically inferior” by Nazi officials. More crassly, she also had hoped Himmler would celebrate the new child with gifts, as he had after the birth of their second child. So she took a baby from a Dachau prisoner and passed it off as her own. Himmler eventually found out and was furious.

Second, Rascher pulled a scam of his own involving antibiotics. While the Allies had access to penicillin during the war, the Germans did not and were offering prizes to anyone who could develop a substitute. Rascher claimed to have found one he called polygal, and he tested it at Dachau with supposedly miraculous results. In reality he had rigged the tests. He started with a control group of prisoners, injecting a festering pus deep inside their legs and letting them languish. But in the group he treated with polygal, he injected the pus much closer to the surface and in much smaller amounts. Little wonder they fared better. (Polygal wasn’t even viable medicine anyway. Sources differ, but Rascher’s phony drug was either saline with fluorescent dye in it or processed beet and apple pectin.) Colleagues suspicious of Rascher’s results soon exposed him as a fraud to SS authorities.

Third, and perhaps most damning, Himmler knew Rascher was running barbaric medical experiments, and given Rascher’s boastful nature Himmler feared the consequences if Germany lost the war and word got out. So in May 1944, after Rascher’s experiments wrapped up, Himmler stripped him of his SS rank and fittingly enough imprisoned him and Nini in Dachau. They were shot in April 1945, two weeks before American troops liberated the camp.

If not for Alexander, Himmler’s efforts to conceal these atrocities might have worked. Imagine a world where murderous Nazi doctors got away with everything—their atrocities unexposed, their reputations unscathed. It seems outrageous, yet it could have happened if not for Alexander’s dogged efforts. And despite the fact that several Nazi researchers escaped punishment at Nuremberg, Alexander ensured they wouldn’t escape the judgment of history.

Equally important, Alexander helped curb future abuse. Again, several German defendants at the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial argued that what they’d done wasn’t illegal, in part because no international regulations governed medical experiments. Disturbed by this gap, Alexander submitted a memo to Allied prosecutors outlining several principles behind ethically sound research, including patient consent. That memo formed the basis of the 1947 Nuremberg Code that now governs work on human subjects around the globe.

After the trial Alexander returned to Boston to resume his medical practice, but he never could escape the macabre. After hearing about 40 Polish concentration-camp inmates who’d been crippled by Josef Mengele’s medical experiments, he arranged for them to travel to the United States for corrective surgery. And in the early 1960s he consulted with local police to help solve the infamous Boston Strangler serial-killer case. He died of cancer in 1985.

Postwar colleagues knew Alexander best for his work on the root causes of neurodegenerative ailments, such as Parkinson’s disease and especially multiple sclerosis. Still, there’s no question that his most enduring contribution to medicine remains the Nuremberg Code, a guide for all research on human subjects and a milestone in the history of medical ethics. Few people today know of the man behind the code—much less the story of how his disappointment and frustration inspired it. Although Alexander couldn’t ensure justice in his own time, he at least helped secure the rights of those who came after.