Distilling—whether alcohol, essences, or perfumes—is one of mankind’s oldest chemical industries. Music is one of mankind’s oldest arts. In Chimie du goût et de l’odorat: ou, Principes pour composer facilement, et à peu de frais, les liqueurs à boire, et les eaux de senteurs (Paris, 1755) Polycarpe Poncelet manages to combine the two. Despite the prominent reference in the title to “the chemistry of taste,” Poncelet’s treatise falls squarely in the genre of early distillation books. It covers the apparatus and general principles of distillation and infusion, and contains recipes for beverages, liquors, and preparations along with information about the virtues of each concoction. After a short section on odors and the preparation of perfumes and oils the book concludes with glossaries of ingredients and chemical terms.

What sets the book apart is its opening theoretical section, “An introductory dissertation on salubrity of liquors and the harmony of flavors.” That the author of a book discussing the production of liquors should testify to the benefit of consuming a digestif after a good meal is not surprising. What catches one’s attention is the theoretical edifice Poncelet constructs around the theory of flavors.

When he writes that “the pleasure of liquors depends on the blending of flavors in a harmonic proportion,” he is not speaking metaphorically. According to his theory, just as sounds consist of vibrations in the air acting on our sense of hearing, flavors consist of stronger or weaker vibrations acting on the gustatory senses. It follows then that there might be “a music for the tongue and for the palate.”

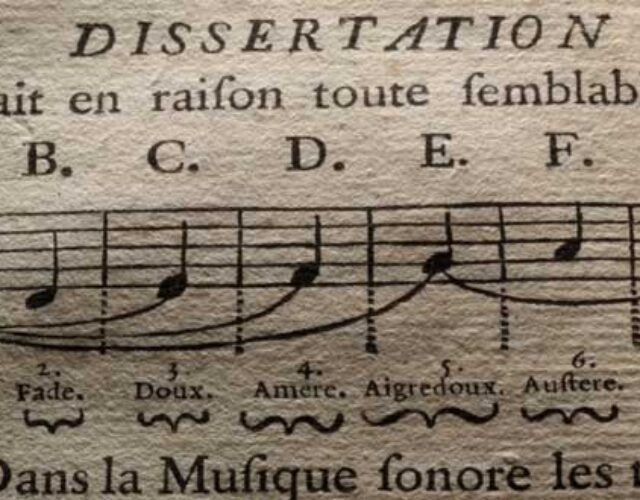

Poncelet proposes seven primitive tastes, similar to the seven notes of the musical scale. According to Poncelet, the tastes are acid, insipid, sweet, bitter, bittersweet, astringent, and pungent. The idea of seven primitive tastes (though not necessarily these seven) goes back to Aristotle, but with Poncelet they are assigned notes on the musical scale: A for acid, B for insipid, and so forth. Thus lemon and sugar produce a “simple, but charming consonance, a major fifth.” In acoustics there are dissonances, and so also with tastes; mix an acid and a bitter, such as vinegar and absinthe, Poncelet says, and the result will be détestable.

“In a word,” he writes, “I regard a well-crafted liquor to be like a kind of musical air. A composer of stews, of preserves, of ratafia, is a symphonist in his genre, and he needs to have a thorough knowledge of nature and the principles of harmony if he wants to excel in his art, the object of which is to produce pleasurable sensations in the soul.”