As far as get-togethers go, Joseph Goldberger’s “filth parties” were rather somber. They took place in medical clinics, with no music and just a handful of guests. And the appetizers, well, they definitely lived up to the party’s unusual name.

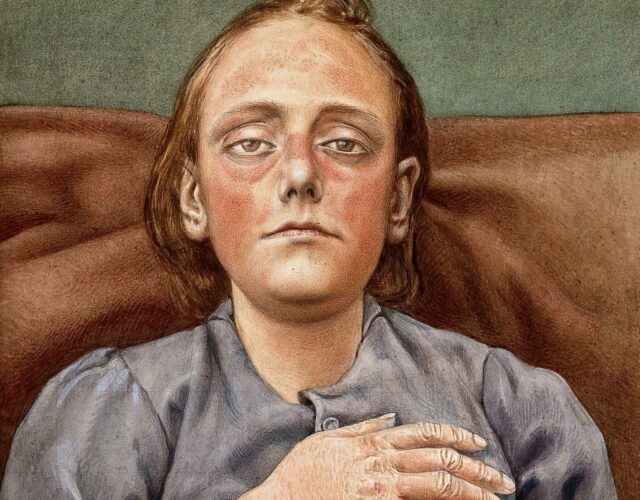

Goldberger—a tall physician with a firm jaw and wavy red hair—studied pellagra, a mysterious disease marked by diarrhea and skin rashes, including butterfly-shaped rashes on the face. Before each meeting he would take scrapings of his patients’ skin scabs, as well as stool and urine samples, and mix these excreta with flour or cracker crumbs, forming small, doughy pills. Then, one by one, no doubt with a sigh or a silent prayer, every party guest would choke down the pills. Indeed, calling these filth parties seems like an understatement.

So what on earth would possess someone to do this? Science, mostly. Goldberger was trying to prove that unlike most epidemic diseases, pellagra was not caused by germs and was therefore not contagious.

But Goldberger was also motivated by outrage. Politicians had been attacking him for his research, calling him a cheat and a liar. Even worse, these attacks prevented his patients from getting help—delays that led to death. Swallowing scabs and feces may sound extreme. But to a true public health crusader such as Goldberger, it was a reasonable response.

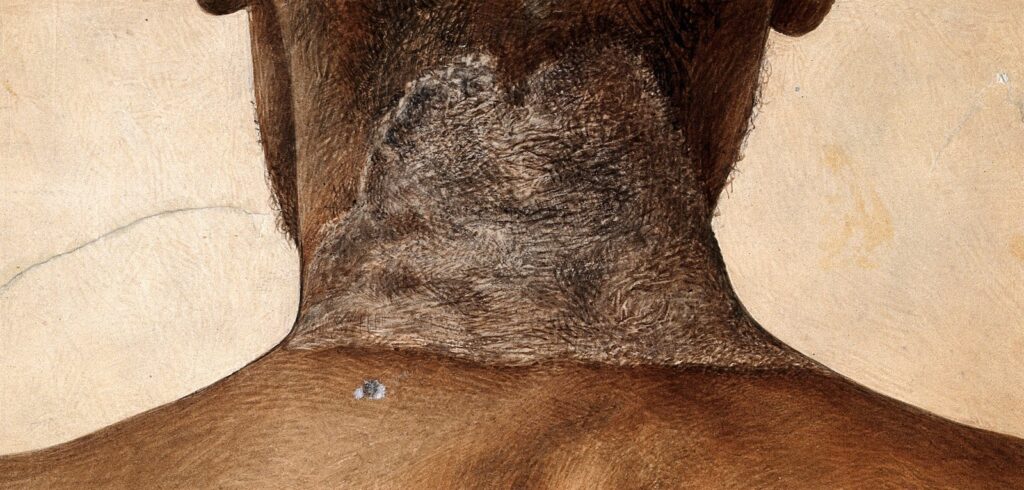

Between 1900 and 1940 the United States recorded three million pellagra cases, with a hundred thousand fatalities. Doctors recognized the disease through the so-called four Ds: diarrhea; dementia; dermatitis, or skin rashes; and death.

Most scientists back then considered pellagra an infectious disease, one spread by microbes. This idea was bolstered by the publication of the privately funded Thompson-McFadden report in 1912. This survey found that just like cholera and typhus, pellagra occurred far more commonly in neighborhoods with poor (or absent) sewers and bad sanitation overall. The report also found that the best predictor of whether someone would get pellagra was whether their neighbors had it, a classic trait of an infectious disease.

Goldberger began investigating pellagra in 1914 on behalf of the U.S. Public Health Service, a government agency devoted to epidemiology. He was shocked by how common the disease was in the South—thousands upon thousands of cases. But after visiting dozens of towns and studying the conditions there, he concluded that the infectious-disease theory didn’t make sense.

His biggest clue came from institutions, such as orphanages and insane asylums. These places had hundreds of cases of pellagra among the wards—but zero cases among the doctors and nurses on staff, even though the staff was in constant contact with pellagra victims. That just didn’t fit with an infectious disease.

Goldberger quickly zeroed in on another likely culprit—a monotonous diet. Back then, many poor Southerners got the majority of their calories from just three foods, known as the three Ms: ground meal, especially cornmeal; molasses, for syrup; and dried meat, especially a type of pork called fatback.

The reason for this monotonous diet was simple: the three Ms were cheap. But other factors contributed as well. Cotton was still king in the South, and to make ends meet, poor farmers and sharecroppers often grew cotton right up to their front door. Doing so left no room for vegetable gardens or livestock that could have introduced more variety into their diets. Even Southern communities with an industrial base, such as cotton mills, suffered. Mill workers often got paid in scrip for use at company stores, which typically carried few groceries—mostly cornmeal, dried meat, and molasses.

To be sure, the three Ms contained plenty of calories. People weren’t starving. But given the dearth of fresh vegetables, fresh meat, and fresh dairy, Goldberger suspected that the diet lacked some essential nutrient. So the doctor set out to prove this theory with a series of experiments.

First, he selected a few orphanages and asylums with high rates of pellagra, and he started feeding people there a more varied diet that included plenty of fresh food—eggs, milk, peas, and oatmeal, among other items. The improvements were dramatic. Rates of pellagra plummeted, and some asylum inmates saw their dementia improve so much that they were discharged.

For his next experiment Goldberger approached the governor of Mississippi and asked for access to a prison near Jackson, one with no reported cases of pellagra. Goldberger proposed isolating a dozen inmates in clean cells to eliminate all chance of infection. He would then feed them a typical Southern diet and see whether they developed pellagra. In exchange the men would receive pardons when the experiment ended. After hearing Goldberger’s pitch the governor agreed to help.

This experiment definitely wouldn’t win approval today, since dangling a pardon in front of prisoners is now considered coercive. But such research was common then, and the experiment went forward in the spring of 1915.

At first the prisoners were over the moon. Their cells were spick and span, and they got all the biscuits, gravy, grits, and syrup they could eat. It was the easiest time they had ever served.

A few months later they were singing a different tune. They all grew weak and pale and started drooping. By November six had full-blown pellagra, and a few could barely walk. One moaned, “I have been through a thousand hells.” Another allegedly asked to be shot. After seven months under observation each man got his pardon, plus five dollars and a new suit. When the prison door opened, Goldberger said, they fled “like scared rabbits.”

Goldberger, though, was thrilled. He had already proved he could stop pellagra by adding fresh food to people’s diets. Now he had proved he could cause pellagra by denying people fresh food. Pellagra wasn’t a germ disease at all but a disease of malnutrition—and ultimately poverty.

This insight also cast the old Thompson-McFadden report in new light. It was certainly true that pellagra thrived in neighborhoods with bad sanitation—but only because bad sewers and bad sanitation infrastructure were also associated with poverty. In a classic blunder the report’s authors had mistaken correlation for causation.

Goldberger now had the key insight needed to stop pellagra: help poor people get fresh food. But if he thought simply publishing this result would put an end to the disease, he was sorely misguided.

For Southern doctors and politicians, having a New York City–born Yankee come in and pin pellagra on Southern poverty stirred up ugly feelings of resentment that dated back to the Civil War. Goldberger wasn’t just highlighting the cause of a disease; he was indicting their entire economic system, their entire way of life.

Soon Southerners were accusing Goldberger of spreading propaganda about pellagra and faking his experimental results. One doctor even denounced him for “crucifying” pellagra victims—a loaded claim to make against the Jewish Goldberger.

This hostility stunned him. He just wanted to cure a disease, not rehash the Civil War. But the more he pushed back, the more his opponents dug in their heels and insisted that pellagra was an infectious disease, unrelated to poverty or malnutrition. Goldberger got so fed up that he decided to do something drastic—an experiment so extreme that no one could refute it. Thus, the filth party was born.

Goldberger hosted eight such parties in the spring of 1916, with 17 different guests total. Most were fellow doctors, but he also included his wife, Mary. As noted, he started by collecting various tissues from pellagra patients—blood, skin scabs, stool samples, and so on. The guests would then receive injections or nasal swabs or eat tablets of the waste mixed with flour or crumbs. As Goldberger later exclaimed, “If anyone ever got pellagra that way, we . . . should certainly have it good and hard! We just feasted on filth.”

After the parties several people were nauseated, understandably. Goldberger himself once came down with diarrhea, one of the dreaded Ds of pellagra. But six months after the parties ended, in late 1916, the partygoers showed no signs of pellagra. They had exposed themselves in the harshest possible way. With cholera or typhus or other diseases, their actions might have been a death sentence; with pellagra nothing happened.

Goldberger’s filth parties won over some skeptics, but predictably his fiercest critics refused to back down. Some even blamed pellagra victims for bringing the disease on themselves through dirty habits and ignorance. One newspaper declared that pellagra “should be a stigma on any housewife.” These continued criticisms left Goldberger in despair. As he once told a reporter, “I’m only a bum doctor. What can I do about the economic conditions of the South?”

Eventually Goldberger turned to laboratory work, hunting for the nutrient missing from the diet of pellagra victims. He found that just a few cents’ worth of brewer’s yeast could eliminate the disease. In fact, yeast helped stop an outbreak of pellagra along the Mississippi River in 1927 after a flood devastated food crops there. But Goldberger wanted to dig down even further, to the specific molecule involved. He suspected it was a vitamin of some sort.

This was a good guess. Research into vitamins had exploded in the early 1900s, and the first Nobel Prize for vitamin work was awarded in 1929. Eight more Nobels for vitamin research followed in the 1930s. And in 1937 a biochemist in Wisconsin finally isolated the molecule whose absence is responsible for pellagra. It’s now called niacin, or vitamin B3. But at the time people called it vitamin G in honor of Joseph Goldberger.

Scientists now know that pellagra is more than a simple deficiency of niacin in diet. Corn actually contains niacin, but our bodies can’t access it. That’s because corn stores the niacin molecule in a form that needs breaking down first. Before contact with Europeans some Native American nations relied heavily on corn for calories, but these people rarely got pellagra because they ground the corn with alkaline water, which freed up the niacin.

Sadly, Goldberger did not live to see the discovery of niacin. He developed kidney cancer and died in 1929, at age 54. To his wife’s dismay she had to fend off rumors that he had died of pellagra. And the attacks on Goldberger’s character continued. A year after his death one South Carolina official compared him to the fascist leader of Italy, Benito Mussolini.

But by following Goldberger’s lead, however fitfully, the United States more or less eliminated pellagra in the decades after his death. The fall of cotton prices during the Great Depression forced sharecroppers to plant a wider variety of crops, increasing their access to fresh produce. New Deal programs then helped spread electricity in the South, allowing more people to use refrigerators to store fresh meat and dairy products. Most important, federal and state laws during World War II mandated the addition of niacin to bread. Nowadays, a disease that once killed hundreds of thousands of people is exceedingly rare in the United States, found mostly in people with anorexia, alcoholism, and other health conditions.

Like pellagra, Goldberger is now little known. But in a topsy-turvy way, that obscurity is actually a measure of his accomplishment. His work eradicated the disease so thoroughly that he effaced himself in the process—a tradeoff such a true public-health champion no doubt would have welcomed.