John Snow left his office at a run. The streets were empty, London a ghost town, for cholera had returned.

Three-quarters of the population had fled, while many without means to leave lay sick or dying in their homes. Though he was a doctor, Snow was not running to treat the sick; he was rushing to the office of the register general, which held the records of those who had recently died from cholera.

Then he started walking.

Snow spent the next two days making on-the-ground inspections and interviewing locals and doctors and two nights combing through government records. Snow went door to door, retracing his steps again and again, trying to fit death counts and sudden illnesses into a picture that made sense. Finally, after walking past the same water pump for what must have felt like the hundredth time, he took everything he had found and plotted it all on a map of the Soho area.

Today, we would call the result a Voronoi diagram, but when people saw it in 1854 they dubbed it a ghost map, one that showed Soho overwhelmed by stacks of black lines, each representing a death by cholera. Several water pumps used by residents are clearly marked on the map, though it takes a moment to notice them; instead, the eye is immediately drawn toward the thick black lines clustering around the epicenter, the location of the Broad Street water pump.

Snow’s research in the preceding decade had indicated that cholera spread through water, but time and again his findings had been ignored and dismissed. He knew the local parish government was unlikely to listen to him. Even so, he had to try. If the commission agreed to remove the pump’s handle—if he could show beyond a shadow of a doubt that the water beneath the Broad Street pump was the source of sickness—then maybe he could prevent further deaths.

Armed with his research and a stubborn resolve to make the medical world listen, Snow, the not-yet father of epidemiology, set out to make his case.

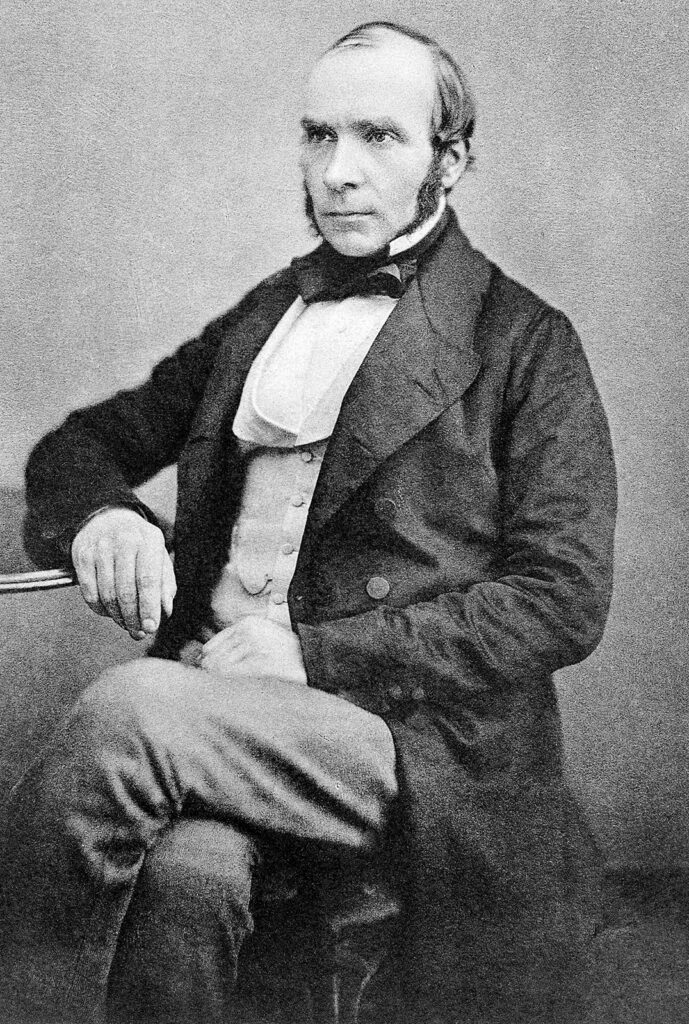

The Doctor

Born in 1813, Snow was inquisitive from the start. Or, as biographer Benjamin Ward Richardson would later put it, he was “very reserved and peculiar—a clever man at bottom perchance, but not easy to be understood and very peculiar.”

Still, his mother insisted that he do something with his intellect, and at age 14 Snow began a medical apprenticeship in Newcastle. He took to his studies with all the fervor and excitement he gave to any challenge. He was a teetotaler, not entirely unusual for the time, and a vegetarian, which was virtually unheard of among the people he knew, including his medical colleagues. Richardson later described how Snow’s vegetarianism “puzzled the housewives, shocked the cooks, and astonished the children.”

Snow’s first significant encounter with cholera occurred in 1832. The second cholera pandemic was sweeping through England, leaving hospitals severely understaffed. Snow, then a 19-year-old apprentice, was sent to care for the workers in the mining village of Killingworth.

At the time, the accepted theory among both doctors and laypeople was that cholera was spread through miasmas—noxious vapors often caused by rotting organic compounds that would, when inhaled, cause sickness. While in Killingworth, Snow kept a journal documenting what he saw, and according to his entries such a theory made no sense. If miasma theory was correct, then workers near the area’s sewage dumps should be getting sick, rather than the miners in the coal pits, as was so often the case. Given that miasmas were inhaled, Snow reasoned that a sickness caused by miasma would most likely begin in the lungs or the throat, but cholera was felt first in the intestines. It was far more likely, he argued, that the “poison” was found in something the locals had ingested.

In 1837, a year after he arrived in London, 24-year-old Snow earned his medical license. The following year he became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons. By 1854, when cholera again struck the city, Snow was a respected and seasoned doctor.

In writing for the Canadian Public Health Journal, J. L. Little paints a remarkable picture of Snow: “If one could combine in a sketch something of an ascetic, a total abstainer, a vegetarian, a bachelor, a lover of children, a devotee of the open heath, and an enthusiast for all things of good report, then we would be presenting John Snow as a man.” Richardson, a colleague and close friend of Snow, offers a similar, albeit drier, description of Snow. Richardson presents a man dedicated to helping members of the lower class and ascribes his lack of wealthy patients to the fact that he “was an earnest man with not the least element of quackery in all his composition, with a retiring manner and a solid scepticism in relation to that routine malpractice which the people love.”

King Cholera

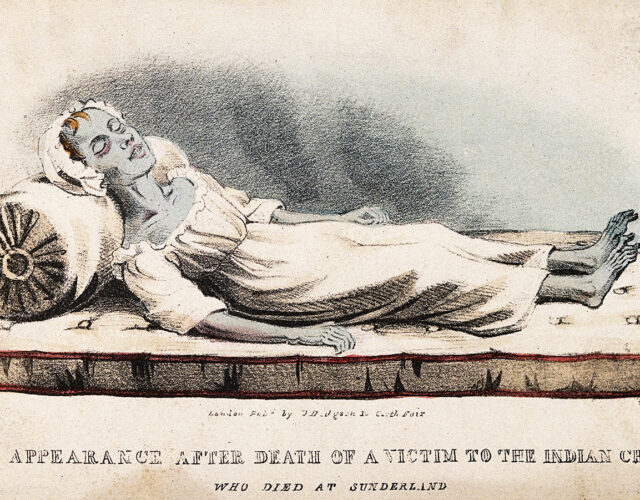

They called it the blue death. As dehydration racked the body, blood would begin to thicken in patients’ veins; starved of oxygen, their skin would turn a sickly shade of blue. Cholera could hit hard and work fast; in severe cases apparently healthy Londoners would drop in the middle of the street and were often dead by the end of the day.

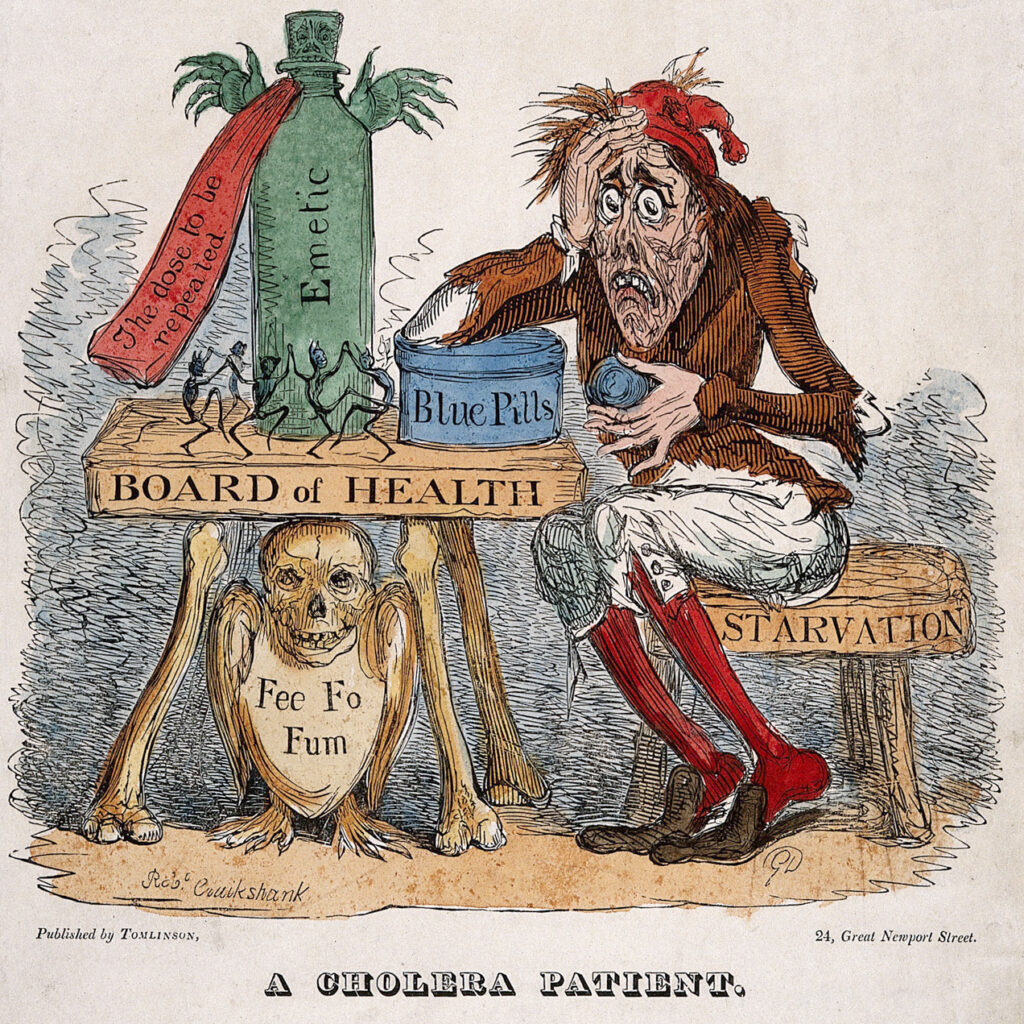

Today cholera is treated with hydration (given either orally or intravenously), electrolytes, and antibiotics. But in the 19th century, treatment was more likely to consist of a vacation to the seaside (which sometimes appeared to work, but in reality did very little), purgatives (the last thing cholera patients needed), leeches, or opium. Because cholera was believed to spread through miasmas, the usual treatment was to remove the patient from the “bad air.” This approach occasionally worked, though not because the patient had been moved to a place with healthier air; rather, they were moved to a place with cleaner water. But only those with milder cases benefited.

While not wholly reliable, a change of scenery worked just enough to reinforce miasmas as the leading suspect in cholera’s proliferation.

At the time, an alternative theory of disease-causing, self-replicating “poisons” had entered medical discourse, but such an idea was still theoretical. Most doctors held to the theory that bodies of water from which Londoners drank, such as the River Thames, would dilute a “poison” past the point of potency, and thus such poisons could not be major sources of disease. One consequence was that sewage was removed from people’s homes and sent straight into the Thames. The river, however, was tidal, its flow intermittent, and London was full of cesspits located dangerously close to wells.

A Broader Look

The story of the Broad Street pump is famously associated with Snow, and it appears in every account of his life. Yet Snow’s story is not that of a man single-handedly ending an epidemic in one glorious act of gritty detective work; it is the story of a doctor’s pursuit of answers over the course of years.

Scattered reports of a strange smell at the Broad Street pump offered the first hint. Snow, however, would have to prove that the problem was not the smell of the water, as miasma theory would have it, but something in the water that was swallowed. After all, his ghost map could be used to argue that living near a pump that emitted a foul odor caused cholera. Snow needed to prove that the water had to be ingested for cholera to spread, and to do that he needed to answer two main questions: why were there such large clusters of people living near the Broad Street pump who weren’t getting sick, and why were there people outside the parameters who were?

Snow interviewed patients, doctors, and local residents and cross-referenced the results with government records. Of those cholera victims who at first glance shouldn’t have drunk from the Broad Street pump, he found that most were schoolchildren or workers who stopped by the pump as part of their daily routine. In the case of two particularly out-of-the-way deaths, the lady of the house had grown fond of Broad Street water when living in the area and after moving had the water delivered to her new house, whereupon it eventually killed her and her visiting niece. As for nearby households that were never affected, all had pumps on the premises, or, in the case of an alehouse, were staffed by workers who almost never drank water during the day thanks to a daily allotment of beer.

Ultimately, it was an impressive enough case to convince the parish government to remove the pump’s handle. But once the epidemic had ended, the handle was returned and Snow’s theories of waterborne disease were left to languish.

A group of local scientists and public figures had attempted to determine the source of the epidemic, with Snow among their number, but most did not favor his theories. One such doubter was Henry Whitehead, a local Anglican priest whose personal mission since the beginning of the epidemic had been to dismiss all notable theories about cholera’s spread—including Snow’s—in favor of his belief that cholera was sent as a punishment from God. But the more Whitehead investigated Snow’s theory, the less he doubted.

It was Whitehead who eventually tracked down the source of the outbreak around Broad Street. The earliest known case, he found, was that of the infant daughter of one of his congregants, who had washed the child’s soiled linens and emptied the dirty water into her house’s cesspit, which was situated in a basement right next to the Broad Street pump; the cesspit was old and its foundation was cracked, causing it to leak directly into the pump’s well.

Water Troubles

Snow first published his thoughts on the disease in 1849 in “On the Mode of Communication of Cholera,” though he was reluctant to make any definitive claims about cholera’s spread without sufficient proof; such was Snow’s way in everything he published. He studied two cholera outbreaks in the London area and in both cases traced the contaminated water back to wells fed from certain stretches of the Thames. Even so, the idea that cholera was largely waterborne was still speculation—highly educated and well-backed speculation, but not a watertight case.

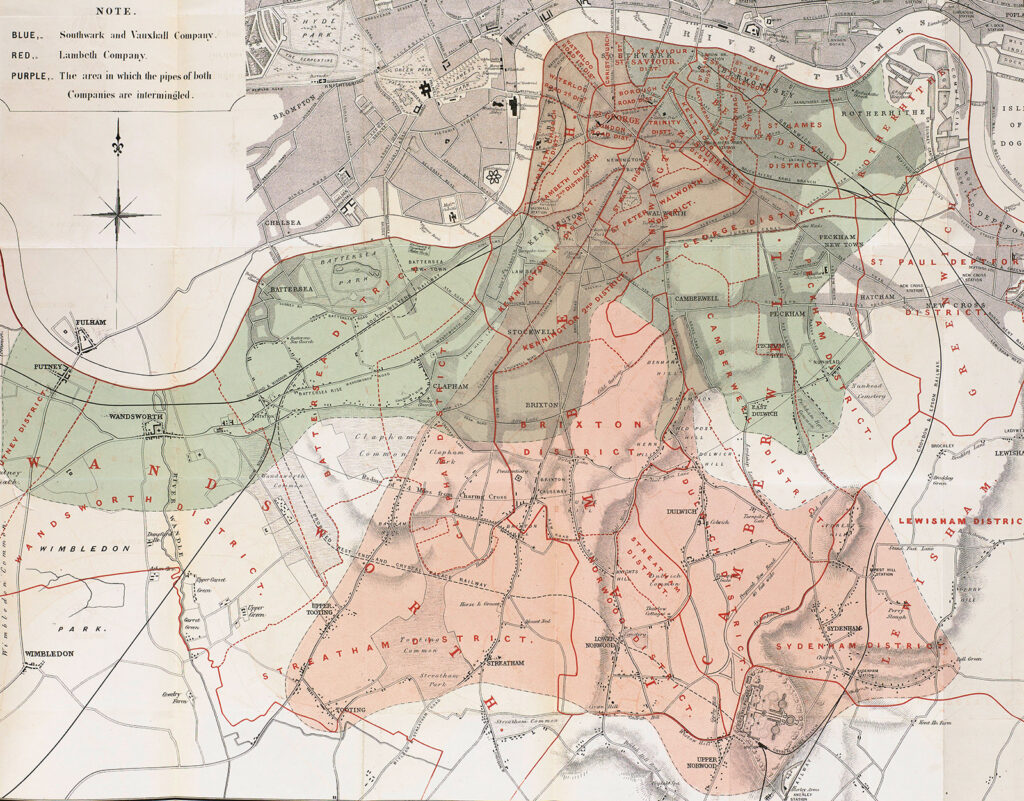

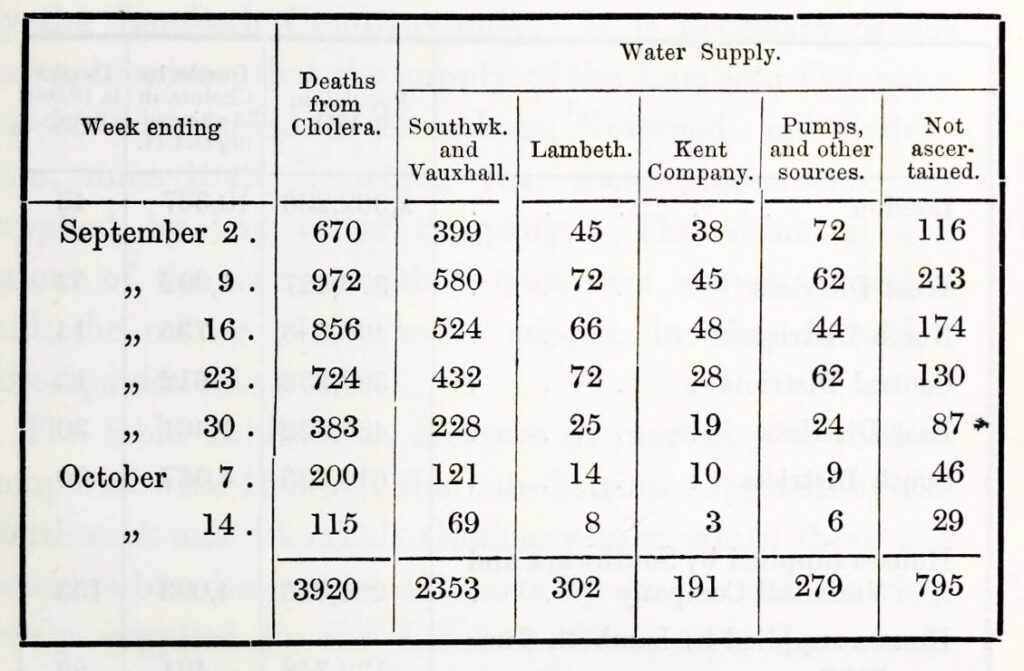

Then, in 1854, sandwiched around his famous work on Broad Street, came the study that helped lay the statistical foundations of epidemiology: the Southwark and Vauxhall and the Lambeth water companies.

Sometime between the epidemic of 1849 and 1853, the Lambeth Waterworks Company changed its water intake from the center of town to Thames Ditton, which was upstream of London’s sewage. Meanwhile, the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company continued to source its water from the Thames at Battersea Fields, downstream of the city’s sewage. Snow dug through water company records and found that cholera struck customers serviced by Lambeth less frequently than those serviced by Southwark and Vauxhall. He set out to measure the difference.

It was, at first glance, the perfect scientific experiment, with clearly defined parameters unmuddied by extraneous factors. Snow describes how “each water company supplied alike both rich and poor, and thus there was a population of 300,000 persons, of various conditions and occupations, intimately mixed together, and divided into two groups by no other circumstance than the difference of water supply.”

The experiment proved to be decidedly less than perfect when Snow realized Southwark and Vauxhall’s organizational system was as inferior as its water source. In a British Medical Journal article published in 1857, Snow described the Lambeth operations and the clearly labeled ledger of customers listed by location. Southwark and Vauxhall, in contrast, had “a kind of alphabetical arrangement” that was no use to Snow; its list was in no real geographical order and could only narrow a customer’s location to within an area of 10 to 15 square miles. Throwing darts at a map of London would be roughly as effective.

As on Broad Street, Snow took to knocking on doors. He and the colleagues working with him double- and triple-checked the water supplier for each cholera death on record. Once Snow had accounted for any possible misreporting, the results proved staggering: mortality rates in Southwark and Vauxhall houses were six times greater than in Lambeth houses.

Snow and his colleagues went over the results repeatedly, ensuring the data was as accurate as possible, to the point where even Snow, far from one to hail his own achievements, hazarded that “it probably supplies a greater amount of statistical evidence than was ever brought to bear on a medical subject.”

Epidemiologist Wade Hampton Frost would later call Snow “a nearly perfect model” for studying epidemiological situations because his analysis “led him to the confident conclusion that the specific cause of the disease was a parasitic micro-organism, conforming in all essentials of its natural history to what is now known of the Vibrio cholerae.”

Snow did not live to see germ theory take hold within the scientific community, nor did he live to see London’s overhaul of its sewer systems and the end of cesspits, but he did get to see some of the short-term results of his epidemiological research.

In 1857, the year before he died, he wrote “On the Origin of the Recent Outbreak of Cholera at West Ham,” in which he noted that “no water company [now] draws its supply from any part of the Thames which is within reach of pollution by the shipping, or the sewers of the town.” Death rates in London decreased significantly in the second half of the pandemic after changes in water supply became more widespread. Within a few years of Snow’s untimely death by stroke, cholera would become a rarity in England.