Last week the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine released a landmark study detailing the effects of sexism and sexual harassment on women in academic science. It found that sexual harassment is pervasive in university science departments, that it regularly drives women from scientific fields, and that current mechanisms for reporting sexual harassment on campuses (such as Title IX, the 1972 law that bans discrimination based on gender) don’t work. The study also made recommendations, among them that research organizations should treat sexual harassment at least as seriously as research misconduct.

It’s hard to be surprised that sexism is a problem in our society after more than a year of #MeToo stories. It’s hard to be shocked at the boorish behavior of men from scientific fields if you’ve ever investigated the lives of scientific “greats” who won Nobel Prizes even as they harassed and mocked their female colleagues. But this study’s findings are enlightening. While the National Academies’ report acknowledges the significance of egregious coercion and violence, it puts particular emphasis on more subtle forms of sexism that women in science experience every day. Often called microaggression, this type of discrimination gives women the impression they do not belong in the lab (or in the field, office, etc.). Paula Johnson, president of Wellesley College in Massachusetts and cochair of the committee that wrote the report, calls this kind of everyday gender harassment “put-downs rather than come-ons” and insists that university departments must change their culture, which has been unwelcoming to women for too long.

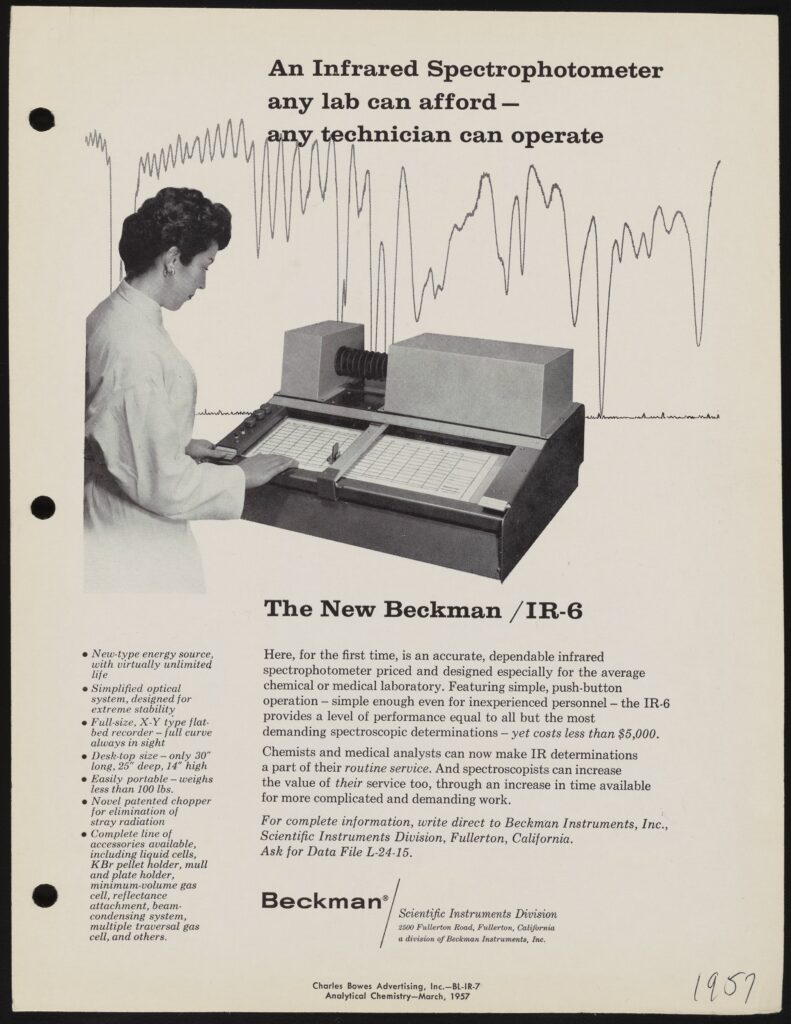

A 1957 advertisement for Beckman Instruments’ IR-6 Spectrophotometer that “any lab can afford—any technician can operate.”

The culture of sexism that Johnson describes has a long history. In 2015 James Grossman, the executive director of the American Historical Association, created the provocative hashtag #EverythingHasAHistory to encourage historians and laypeople alike to consider the historical roots of contemporary social, political, and cultural issues. I had to search our own digital collections for just a few minutes to find examples in ads, promotional images, and reports that demonstrate exactly the kind of sexist culture that, in ways subtle and unsubtle, has reminded women for centuries they do not belong in the sciences.

A surprising number of publicity photos and advertisements from the 1950s and 1960s show women using scientific instruments, but I wouldn’t call these images “empowering.” Marie Hicks, author of Programmed Inequality, has observed that women were used in ads selling computers and scientific instruments to imply (or even state outright) that the equipment was easy to use. What’s more, women could be hired on the cheap as lab technicians and wouldn’t, it was assumed, stick around very long. Even when being depicted as actually doing science, the women in mid-century ads and publicity photos weren’t being treated as scientists; at best, they were disposable extensions of the machines themselves.

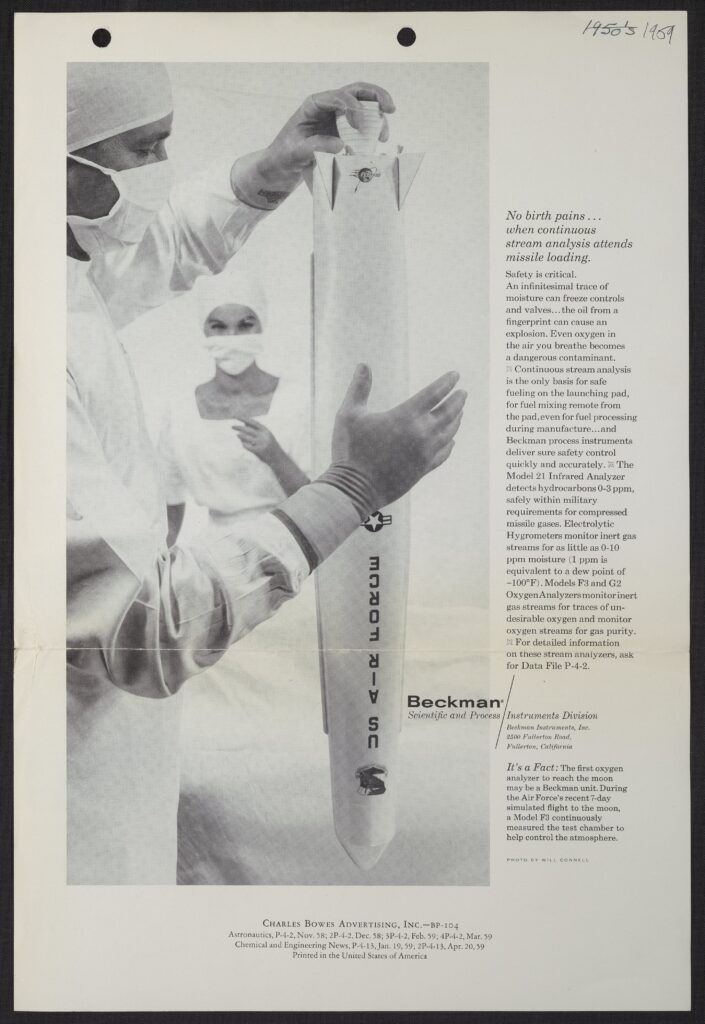

A 1959 advertisement featuring a nurse looking at a physician who has delivered an Air Force missile.

Sometimes the sexism in these ads is just plain weird. In the ad above for Beckman Instruments a scientist plays doctor to a newly “birthed” nuclear missile while lurking in the background is a woman (a nurse perhaps?) ready to lend a hand. Along with emphasizing the societal assumption that obstetricians are male and nurses are female, the ad suggests that inventing and manufacturing a rocket is like giving birth. It conveys a world where men have all the power, controlling events both in the maternity ward and in the scientific laboratory.

Deanna Day, one of our Beckman Legacy Project research fellows, recently did her own analysis of the very same ad. She notes that the 20th-century missile industry was full of gendered metaphors. Nuclear scientists called dud bombs “girls” and gave notoriously destructive atomic missiles such names as “Fat Man” and “Little Boy.” “The metaphor of birth gives men the illusion of the power they wish they had,” she observes. “They cannot create life, but they can destroy it.” The not-so-subtle implication in this ad is that the hypermasculine “baby” rocket has far more power than either the distant nurse or the unseen mother.

When we come across blatant sexism in the historical record, it’s easy to dismiss its importance by saying, “Well, that’s just how it was back then.” But the messages conveyed in these documents—and so many others like them—have had long-term consequences. The National Academies’ report confirms that women are still expected to remain in subordinate roles in science, are sexualized in the workplace, and are maligned for doing their jobs. The report solidifies what so many of us have long known: that promoting women in science doesn’t just mean getting more women into science. It means changing the long-standing sexist culture within science—and the rest of society—as well.