Melanie A. Kiechle. Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban America. University of Washington Press, 2017. 352 pp. $35.

We sophisticated, modern Americans do our best to ward off suspect odors. Whole supermarket shelves are crowded with liquids that diffuse silently in our rooms, promising alpine freshness or flowery camouflage. Even more shelves offer row after row of products to be rubbed on or sprayed to ensure we smell like cucumbers or pine or menthol—anything but sweaty human beings. Teenaged boys have recently seized on sexy scents as the way to make themselves irresistible to intimidatingly female people. Entire households have thrown open their windows to defumigate the enthusiastic dousings of earnest and insecure teens trying to scent themselves into coolness. (If a bit of body spray is good, surely a good, long burst will be better?)

Hasn’t it always been this way? Haven’t people always wanted to make things smell a bit more pleasant?

Yes and no. In Smell Detectives, historian Melanie Kiechle shows us the ways in which bad smell was not just an inconvenience or a mild embarrassment to 19th-century Americans, but also a potentially lethal threat to growing cities and the people living in them. In a world before germ theory—or before it was widely comprehended and incorporated—foul miasmas were understood to spread disease. Corrupted and diseased air spread illness from person to person and from foul environments to vulnerable human bodies, leaving behind weakness and infection. Eliminating odor was not just about creating a more pleasant environment; it was one front in a constant war against disease and debility. Nasty odors were the first clue to bad airs that could kill children, weaken laborers, or cripple a family. Combating them was a priority for anxious mothers and ambitious city bureaucrats, experimental scientists and hard-pressed Civil War commanders. Kiechle takes us into their world.

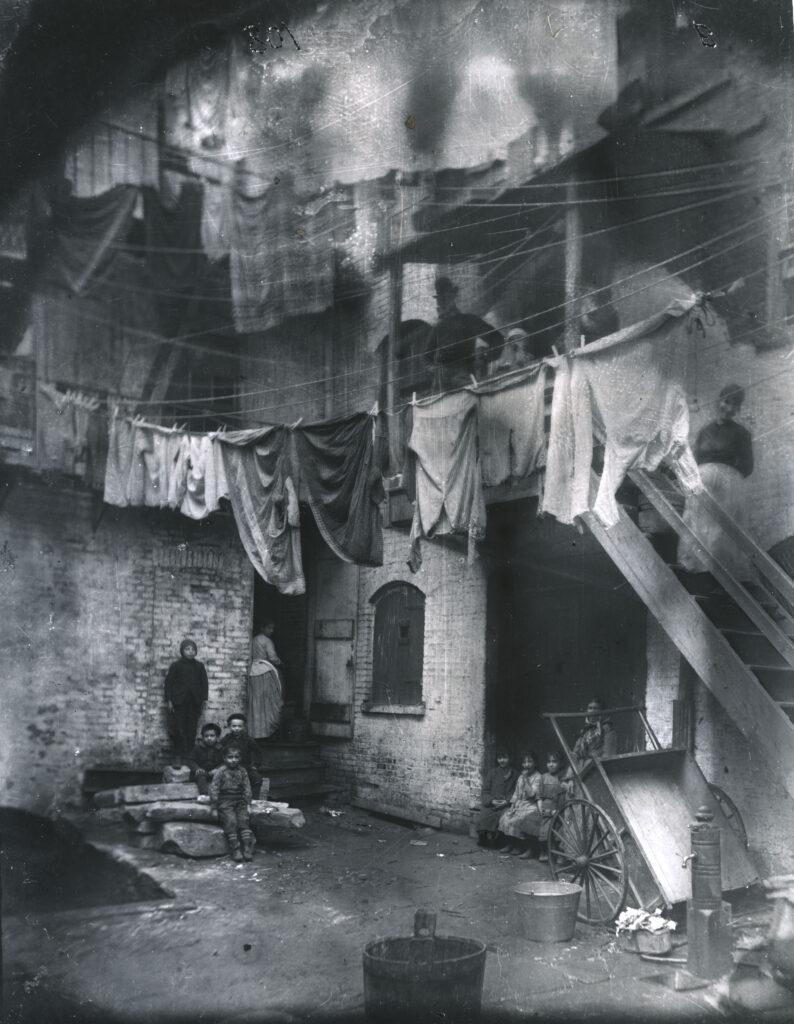

In the 1800s, longtime residents of booming American cities saw their gardens disappear amid tenements and omnibus tracks, and had their access to clean water blocked by new factories that belched out smoke and foul waste, such as “sludge acid,” a wretched-smelling combination of spent acid and contaminants that was a by-product of oil refining. New immigrants were as bewildered by the stench of tanning and industrial production as they were by the language and customs of their new home. Yet all these 19th-century city dwellers knew that the offensive odors floating off free-running open sewers and billowing out of nearby factories were not just unpleasant but physically dangerous.

Photograph of a tenement yard on the Lower East Side of New York City, from social reformer and muckraker Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1890).

In one notorious episode in 1873 the sides of houses in East Cambridge, Massachusetts, changed color overnight. Residents awoke to find their homes blackened and their silver tarnished. Modern Americans might trace these effects to the changed chemistry of the air, but people at the time knew what had happened: the horrible stenches of Miller’s River, long an industrial dumping ground, had gotten so bad they had become visible. For the people whose homes were suddenly discolored, this transformation simply showed the power of what they could sense: factories creating repugnant odors were changing the environment and had to be stopped.

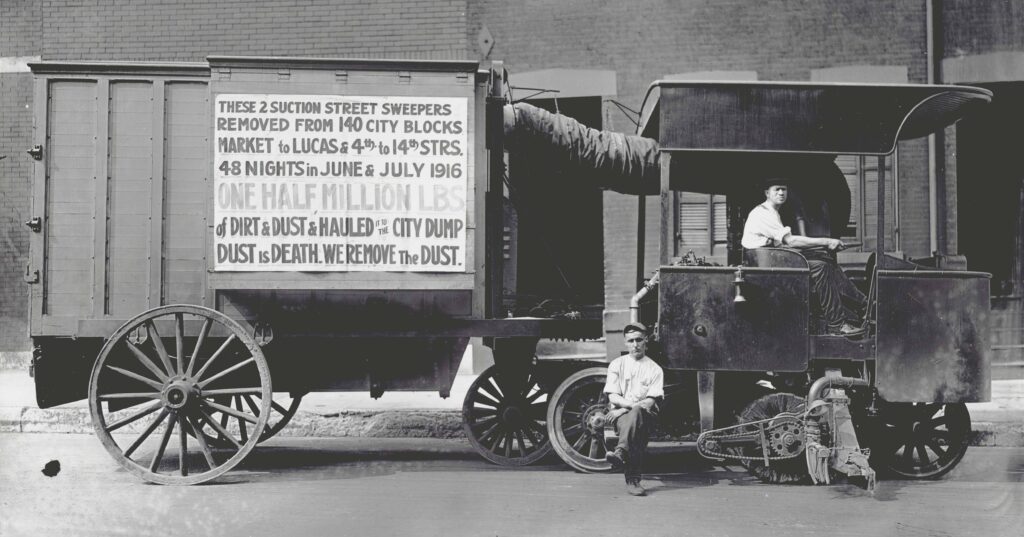

Assaulted by stench, urban Americans were driven to action. They struggled to expel butchers from next door and agitated for city street cleaning. Urban women complained to their shopkeeper neighbors about offal in the streets. “Armed with a range of olfactory reliefs,” notes Kiechle, “from handkerchiefs to fruit stands to the language of nuisance, urbanites navigated their changing experience by nose.” We might be tempted to see their apron-flapping indignation as somehow quaint, but to city dwellers of the 1800s such agitation was a vital defense of families, neighborhoods, and well-being.

“Spare us!” cried Chicago’s editorial writers, from stench that “permeates our buildings and mingles its nastiness with the air we breathe.” In response the city reengineered its river, reversing the flow of the Chicago River to carry waste away from Lake Michigan and thus away from the long-suffering city center.

In city after city idealistic reformers and recently professionalized engineers set out to address stifling tenements and odiferous industries. In fact, Kiechle argues that engineers justified their new status in part by claiming authority over environmental phenomena, including bad smells. When the sources of a city’s drinking water—such as the canal in Providence, Rhode Island—began to reek of dumped carcasses and industrial effluent, medical professionals and civic agitators alike called for better drainage, more consistent waste removal, and regulations that would move smelly establishments outside city limits. When tall buildings stifled fresh, healthful breezes, city planners put in parks to supply “lungs” for cities badly in need of them. Kiechle shows that many features that might seem incidental or even decorative about city life—from medical statistics to blossoming trees along city boulevards—were direct responses to foul stench.

A 19th-century brass fumigator, probably from Spain. Fumigators were used to burn herbs and other sweet-smelling plants to overpower disease-causing stenches.

Chemists were a vital part of this assault against dangerous odor: they used chemical analysis to bring quantitative force and the persuasive power of expertise to documenting, tracing, and eliminating terrible, threatening smells. Brandishing strips of paper darkened by the “filthy compound” of smelly and polluted river water, experts in chemistry demonstrated that science had a place alongside common sense in agitating for livable cities.

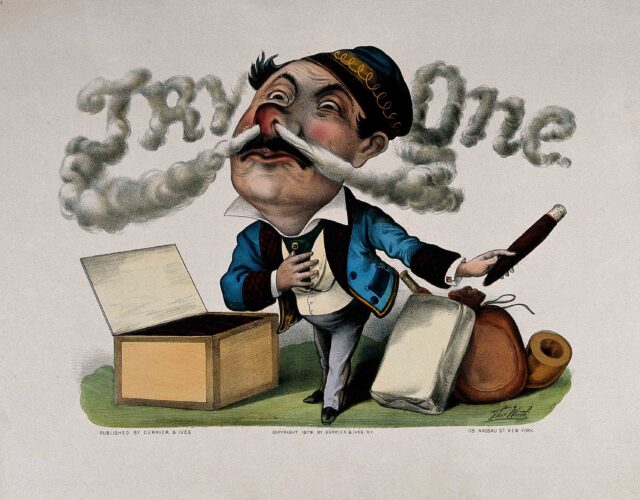

Smell Detectives shows us the detection put into place by this earlier generation of Americans, but Kiechle’s title is itself a play on words. She sorts clues about 19th-century stench, carefully investigating the different meanings of various smells and the reasons behind many easy-to-overlook practices. Setting a bouquet by the door might today seem like no more than classy design, but at the time placing scented flowers by the entrance to a house or planting them in front window boxes were medical interventions meant to neutralize infective odors streaming in from packed city streets. Strong cigar smoke nowadays might seem an unhealthy throwback, but Kiechle’s investigation shows us that the powerful smell of a stogie could be salubrious: strong odor was one way to fumigate and clear out potentially infectious miasma.

Noisome smell even affected city governance. “Smelling committees” were sent out by city bureaus to follow odiferous trails of dangerous stinks back to their origins. Officials designated to report on stench found themselves buttonholed on city sidewalks by offended passersby and roused out of bed by enraged citizens unable to sleep because of unusual or worse-than-usual polluted air. Sniffing the currents, both experts and ordinary residents strained to discern which factory gave rise to which odor, gathering olfactory evidence for debates over zoning that shape our cities to this day.

Smell likewise shaped medical practice in the military. Civil War officers demanded new kinds of tents that would roll up from the bottom to allow healthful fresh air to flow freely: this was no nicety but a crucial means of keeping soldiers in fighting shape. When they moved troops swiftly away from the stench of corpses, this wasn’t just to preserve morale but to preserve bodily well-being.

A street sweeper in St. Louis, Missouri, ca. 1916. The fight against stench brought about all kinds of now-common urban infrastructure, from trash collection and sewer systems to municipal parks.

Much of Smell Detectives concerns a world before germ theory. But one subtle brilliance of the book is to show us how slowly and partially the revolution of scientific thinking had its impact. As Americans figured out what stench meant, they mostly ignored germs. Instead, they bickered over who had authority to show why something smelled bad: city sanitation experts or the people who lived in plumes of wafting odors.

Kiechle uses language nimbly and with insight. It is hard, after all, to find a vocabulary for smells, which most of us nonexperts can describe only by association. “I can conjure the discordant honking and shouting of angry drivers or the post-rain greenery of my lawn with words,” writes Kiechle, adding “you likely have those sounds and sights in your mind right now.” Yet in contrast to vivid descriptors of sight and sound, the language of smell works only by comparison: things stink of hard-boiled eggs, have an odor like cloves, or reek like old onions. Because nasty odor is itself taboo, we possess an impoverished language for describing stench. Historians have to do double duty, both recovering the serious discussion of bad smell in the historical record and conveying the scent and the impact of foul odors of the past.

The author also shows how visual media, especially newspaper illustrations, contributed to a change in the way people perceived the environmental dangers of bad odors, a change that ultimately undercut the war against bad smells. Just as smells are hard to describe in words, so too are they hard to picture. In the mid-19th century, artists drew smoke coming out of factories as a handy way to illustrate stench. (The wavy “stink lines” of comic strips and anime were still to come.) But what was at first a visual referent to foul odor soon took on a meaning of its own. Smoke, pointed to by proud mid-century city leaders as proof of booming industries, became instead a problem. By the end of the 19th century smoke itself was proven harmful, as chemists taught Americans about the health impacts of industrial pollution. Not only would the smells from tanning pits sicken residents; so would the sooty haze billowing from nearby smokestacks. As reformers began to fight against smoke they could see, they began to abandon the fight to make air smell less foul. And by giving primacy to visual evidence, they let stench creep across the urban landscape unabated.

Today, smells still matter. Kiechle bookends her historical detective work with descriptions of present-day smells that have alarmed American cities. One, a strange maple-sugar scent that drifted over New York City in 2005, was nothing more than an unusual odor wafting from a candy factory. Streets that smelled like pancakes were just another funny quirk of big-city life but not a cause for alarm. Another, an innocuous scent of licorice coming from West Virginia’s Elk River in 2014, was the first sign of toxic contamination of a water supply used by 300,000 people around Charleston. The “impromptu smelling committee” of first responders who gathered around a leaking vat in a coal-processing plant used their noses to trace and quash a threat (4-methyl-1-cyclohexanemethanol), just like their 19th-century counterparts. Even for us modern, body-spraying, germ theory–abiding Americans, smells can warn us of dangerous changes to the environments we live in. “If you smell something,” concludes Kiechle, “say something.”