How do you display a hoatzin? The short answer is you don’t, because you can’t. Over the course of the last 115 years, zoos around the world have tried—and mostly failed—to collect, transport, and exhibit these mysterious birds. Less than ten have made it to a zoo alive, and the few survivors never lived long. Why, you ask, would zoos continue to pursue such a seemingly futile (and frequently deadly) endeavor? The answer involves the scientific goals of 19th-century zoos, the lure of seemingly “exotic” tropical creatures, and, more often than not, sheer stubbornness.

The hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin) is about the size of a small turkey or large pheasant and has a blue face crowned by a row of spiky yellow feathers. Two sets of claws adorn each forelimb, which the young birds use to climb through the mangrove trees and marshy plants they live on. Using a digestive process similar to a cow’s, hoatzin ferment the leaves of the plants they eat in a specialized digestive organ known as a crop. Because of this, they smell strongly of manure. While most birds have a crop, the hoatzin’s is so large that the bird’s sternum is quite small and flattened compared to that of other birds. This makes it difficult for the hoatzin to fly long distances, but easier for the bird to rest its top-heavy body on nearby branches while it digests.

The first curator of birds at the Bronx Zoo, William Beebe, believed the hoatzin was a living link between ancient reptiles and birds. He observed that hoatzin move in a peculiar way—when threatened, hoatzin chicks fling themselves into the water beneath their nests and remain there until the predator has passed. The birds use their clawed wings to climb back up on all fours—wings and feet—like a feathered lizard creeping among the leaves. In a 1917 article for the Atlantic Monthly, Beebe likened them to Hesperornis, an extinct aquatic creature from the Late Cretaceous period:

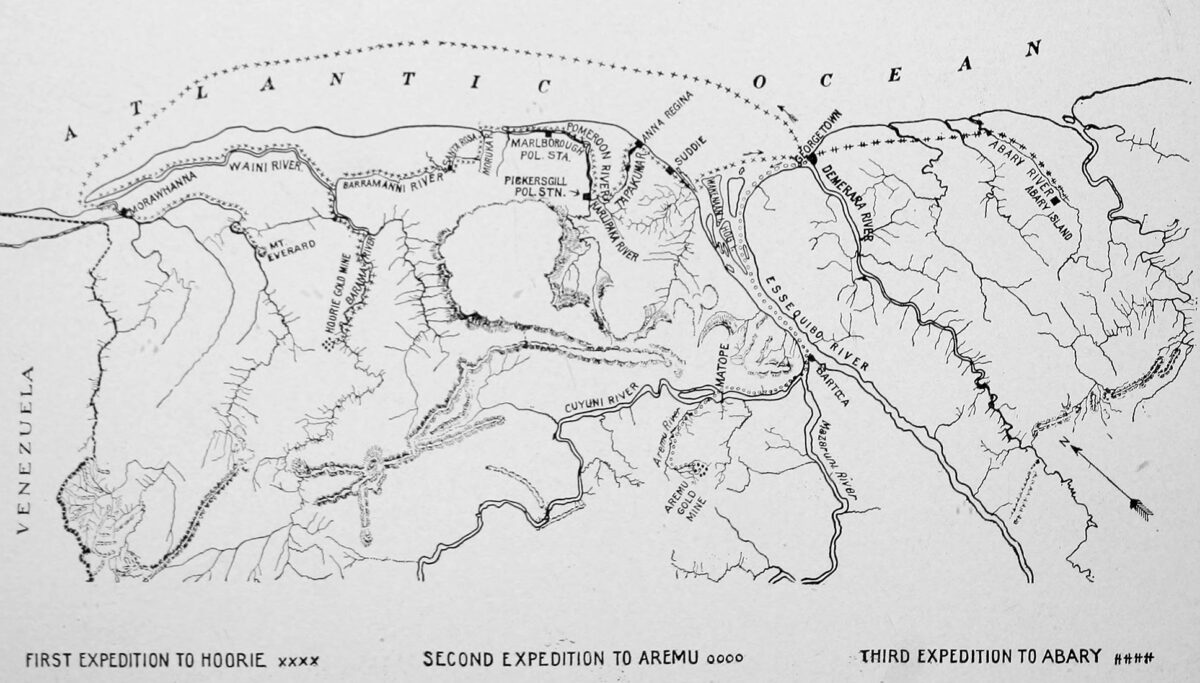

Beebe felt that studying the bird’s movements could yield a deeper understanding of how evolution worked. In 1908, he began shipping scores of these birds from British Guiana (now Guyana) north to New York. He saw hoatzin as the ideal zoo animal—they were scientifically compelling, abundant in South America, and visually interesting to the average zoogoer. But none of the birds he shipped north survived the boat ride; once aboard, most perished within a day or two despite Beebe’s meticulous attention to the bird’s diet and temperature, even housing them in a first-class cabin. Undeterred, Beebe continued to collect hoatzin for more than a decade and vowed to bring the birds to the Bronx even if he had to “exterminate them” in British Guiana entirely.

The Quest

Born July 29, 1877, in Brooklyn, New York, and raised in the wealthy township of East Orange, New Jersey, Charles William Beebe showed an interest in natural history from an early age. He excelled in zoology and embryology at Columbia College, and in 1899, before completing his final semester, he was offered a position at the soon-to-be-opened New York Zoological Park (the official name of the Bronx Zoo when it opened).

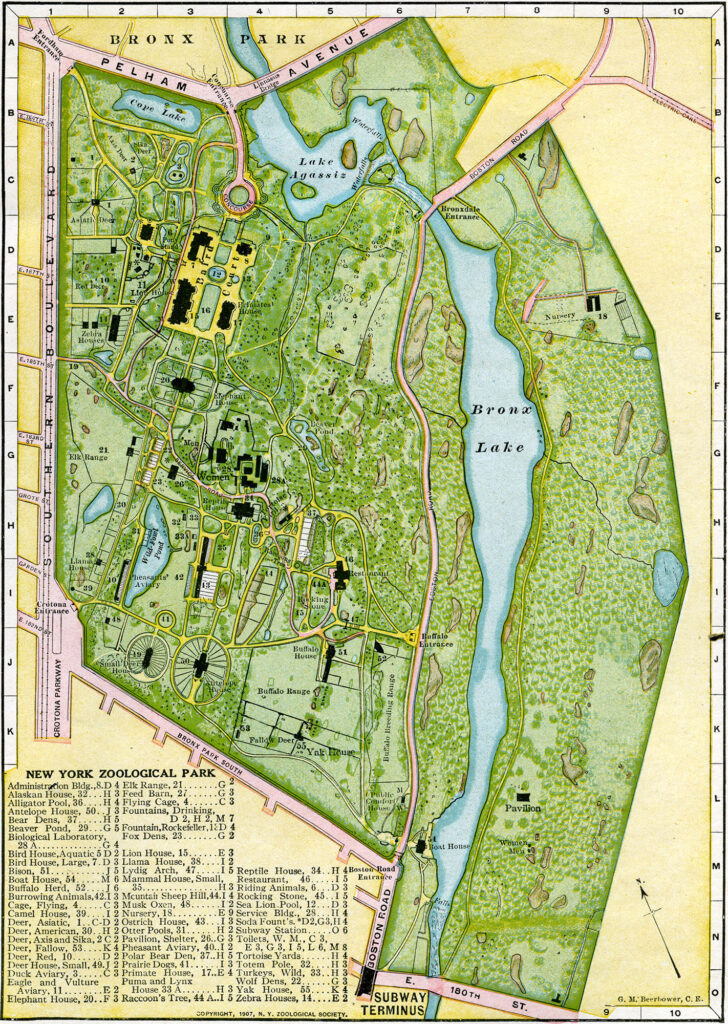

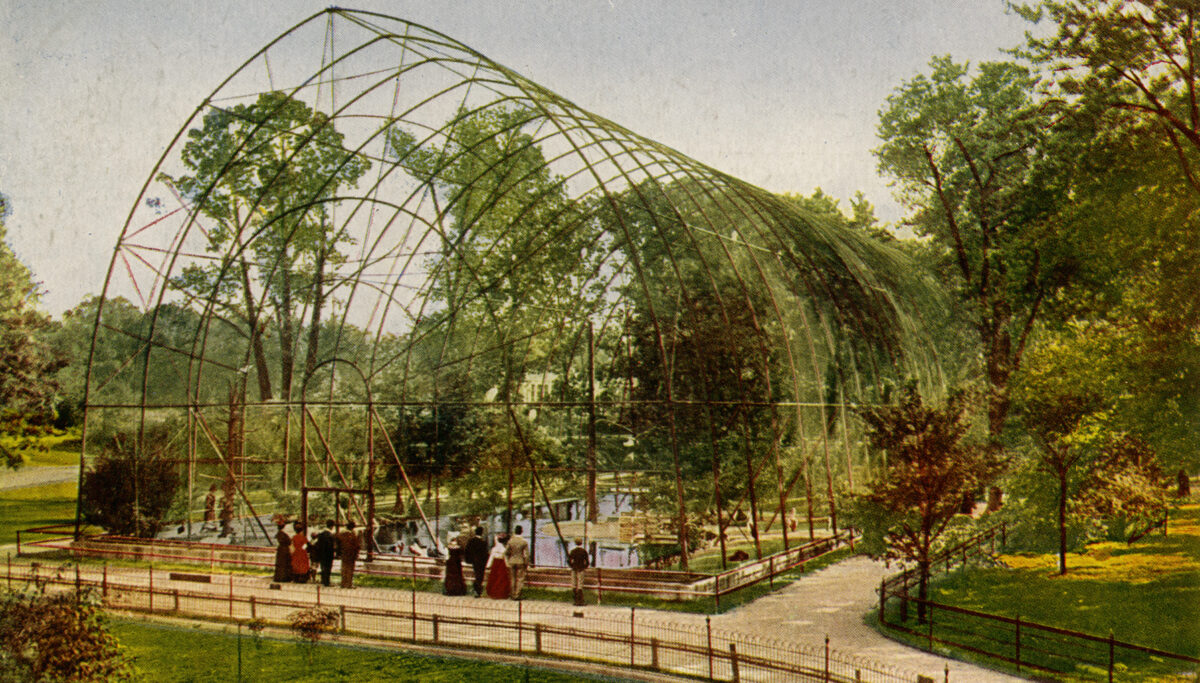

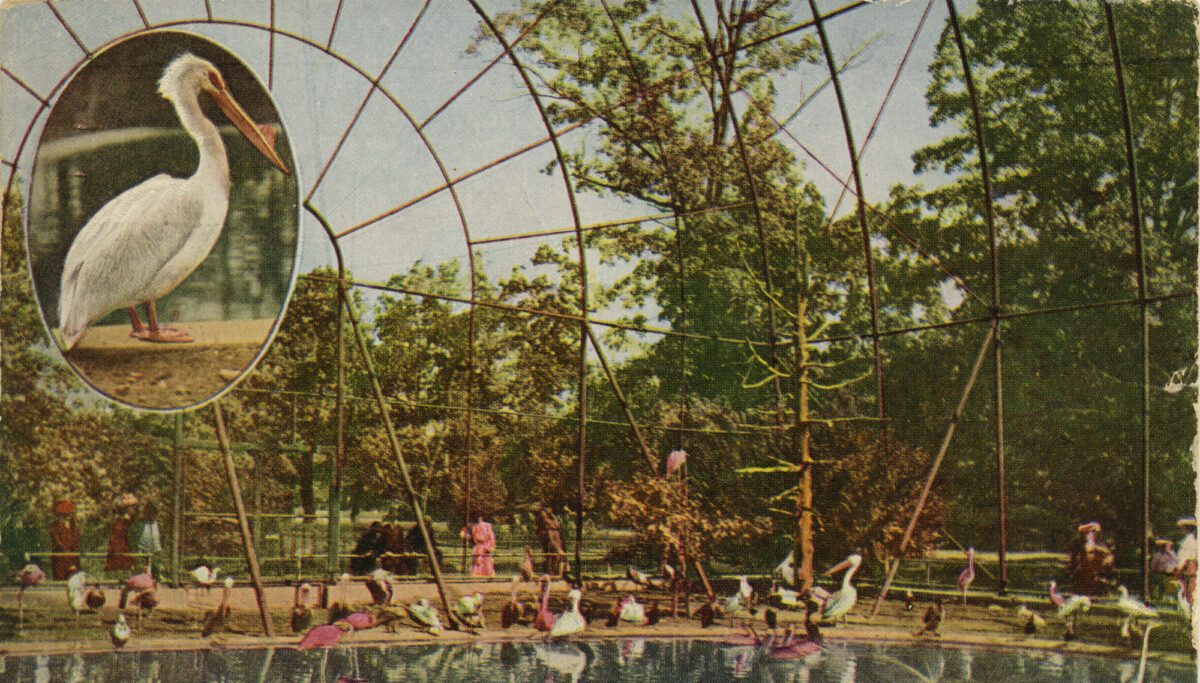

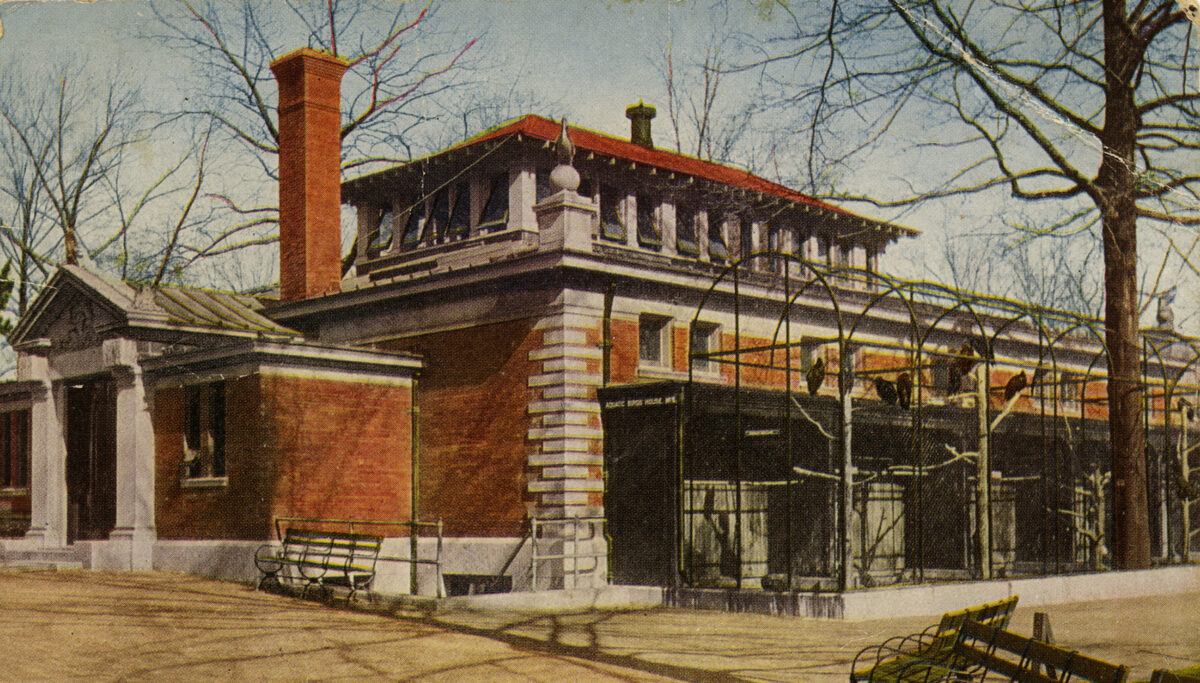

The Bronx Zoo administration’s ambitious goal of turning the new park into the largest zoo in the world—both in total area and number of species represented—monopolized most of Beebe’s attention during his first few years as an employee. He oversaw what was then called “Bird Valley” in the northwestern section of the park. Bird Valley began as a collection of about 185 birds housed across three sites: the Ducks Aviary (a semi-enclosed group of islands amid a large pond housing ducks, geese, swans, and pelicans), the outdoor Flying Cage (constructed for “showy water birds” such as heron, storks, and flamingos), and the Aquatic Bird House (which contained a smaller aviary in the center and was ringed with cages housing perching birds, a tank for diving birds, and enclosures for birds of prey around the building’s exterior).

By 1910, Beebe had enlarged the bird collection to more than 3,000 individual animals, and Bird Valley grew to include a Pheasant Aviary, Pelican House, Small Bird House, Ostrich House, and Large Bird House. As the department’s head curator, he aimed to make the bird department “as fully representative as possible of the birds of North and South America” and tried to group birds from similar geographic regions together, for educational as well as practical reasons. At the time, grouping birds by geographic region was relatively rare, and Beebe’s methods were considered innovative. In the spring Beebe tried to breed and hatch as many birds as possible; in the winter months he struggled to move crowds of unruly flamingos and herons into the few existing heated buildings in the park, even commandeering the Reptile House’s staff lunchroom.

In a 1901 lecture before the Linnaean Society of New York, Beebe tried to explain why most zoos at the time were “so unproductive of Scientific Results.” He hypothesized that an overabundance of information distracted scientists to the point of failure, suggesting that “if we start to study a living bird’s flight, it may lay an egg which will direct us to oology and embryology, or some trait of intelligence will direct us to psychology.” Beebe explained that while traditional methods of studying animal life that used preserved bodies, skins, and skeletons could proceed without distraction in the backrooms of natural history museums, the unpredictable behavior of living animals in zoos offered overwhelming opportunities for new research. With his new position at the zoo, he hoped to manage these distractions by developing a new way to do biological research that used the unique qualities of the Bronx’s animal displays, and, hopefully, turn the institution into a cutting-edge research hub for the study of animal behavior and evolution.

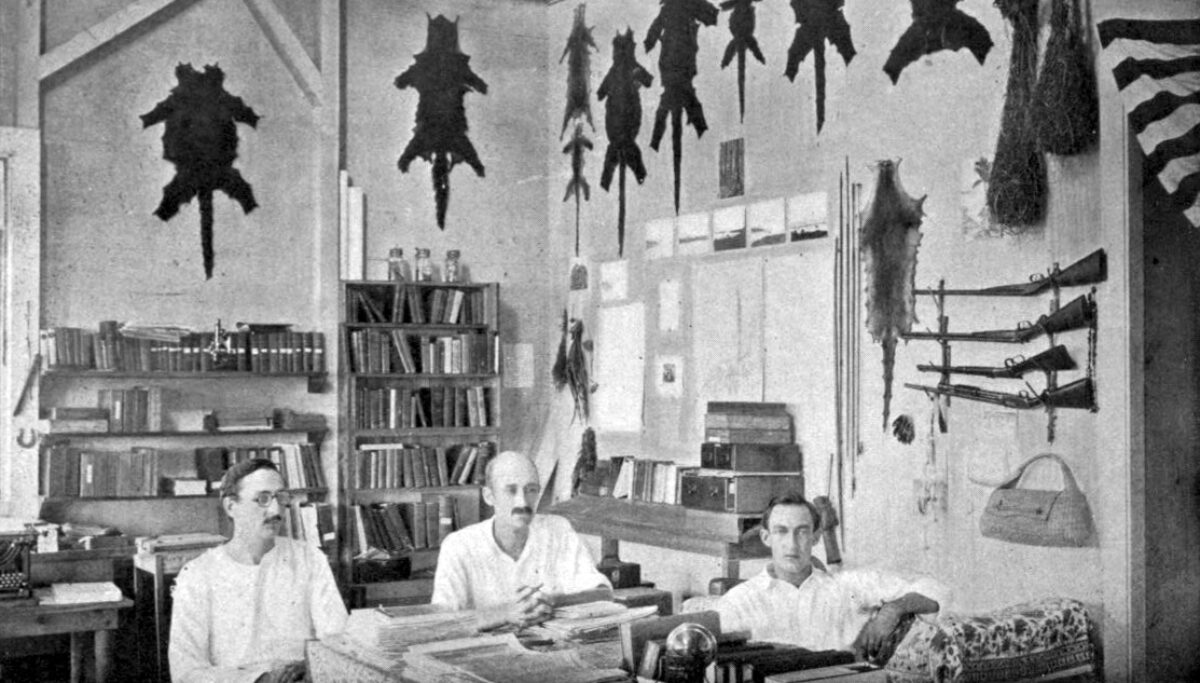

The potential for distraction Beebe described in his lecture was not hyperbole. Soon after starting work at the zoo, he began a series of experiments in such far-ranging topics as bird psychology, the effects of humidity on plumage coloration, and an investigation into the behavioral origins of tail-feather shape in captive motmots. The zoo provided easy access to live birds that facilitated the behavioral and psychological research Beebe wanted to do, and within the small office he was given in the Bird House he could breed animals and create an experimental space where he hoped to control various aspects of his avian test subjects’ environment, including isolating them from the noisy visiting public and other captive creatures. Initially, this office fulfilled most of Beebe’s experimental needs. He kept his library of scientific bird literature there, as well as his box of Grape-Nuts cereal (his preferred midday snack). But, perhaps due to the Grape-Nuts, the room was soon overwhelmed by cockroaches and Beebe, feeling helpless, had to abandon his once-promising laboratory. “The cockroaches are still eating my books and I am helpless,” he wrote in his journal on August 31, 1900.

In one of Beebe’s first zoo experiments, he claimed to have induced a “true mesmeric condition” in a captive parrot by first partially mesmerizing himself and then staring fixedly at the bird from across the expanse of his office. This put bird and man into a shared trance, which, Beebe claimed, allowed him to use the powers of his mind to compel the parrot to repeatedly lift a morsel of food to its beak. Captive catbirds, various owls, and Beebe’s friend from college, Seward Wallace, were similarly subjected to this attempted mind control. According to a 1903 article in the Saint Paul Globe, Beebe believed that establishing a telepathic connection with the birds under his care would allow him to develop a “novel method of communicating ideas and receiving knowledge” from otherwise inscrutable creatures. He admitted that his tests were far from conclusive but believed that the birds’ (and Wallace’s) ability to be mesmerized showed that they had a well-developed “subjective mind”—an inner world that indicated a much higher degree of intelligence and individuality than previously recognized by the scientific community.

When the Bronx Zoo opened, the wider field of biological study in the United States was undergoing a process of rapid expansion, professionalization, and increased specialization. Many U.S. zoologists began to direct their attention to questions of organismal function, development, and behavior instead of focusing solely on morphology (an animal’s bodily form) and systematics (the classification and evolutionary relationship between different organisms). With his mesmerism experiments and later work on animal behavior and evolutionary development, Beebe hoped to join this movement, but he faced significant obstacles before he could do so.

The new trends in biology were led, for the most part, by university-sponsored laboratories and established institutional research centers. Zoos were known as entertainment venues, not as places that produced serious biological research. To make matters more difficult, both Beebe and the New York Zoological Park possessed none of the legitimating markers recognized by the emerging professional scientific community. Although Beebe had taken three years of classes at Columbia College, he did not hold an undergraduate degree, let alone any higher educational distinctions. Although members of the zoo’s administration held faculty positions at prestigious universities, most of its curators and employees did not. And, unlike more established scientific institutions at the time, the Bronx Zoo lacked any kind of degree-granting educational program or formal research program, which made it difficult to build an engaged professional community to support and promote their scientific project.

Beebe was convinced that if he could watch the birds long enough and “with sufficient keenness and controlled imagination, some significant hint of avian evolution is certain, sooner or later, to be revealed.”

Burdened by these institutional limitations, his lack of experimental space, and, increasingly, disagreements with the zoo administration, in the early 1900s Beebe laid out plans for a new kind of living laboratory that would take him out of the Bronx and into the tropical jungle. Inspired by a few short collecting trips through southern Mexico and northern South America, Beebe latched onto the idea that the only way to achieve biologically significant scientific results about animal behavior was through prolonged research in an animal’s own habitat. This shift was, in part, hastened by Beebe’s desire to bring hoatzin to the zoo. He hoped that by establishing a permanent field station near hoatzin territory, he could figure out how to keep the birds alive in captivity and establish a steady supply of the birds that he could use for research and sell to northern zoos.

Beebe first encountered living hoatzin in 1908 while visiting a large pitch lake with his first wife, Mary Blair Beebe (née Rice), near Guanoco in northern Venezuela. Although the birds were not his initial reason for making the trip, on his return Beebe announced that the special purpose of this expedition was “to study at close range and to add to the fund of existing information concerning the hoatzin, a strange equatorial bird with reptile-like characteristics.” This signaled the beginning of Beebe’s 16-year pursuit of an animal he intermittently described as ancient, helpless, an “over-fed hen,” and the most profound encounter of his entire life.

The uniqueness of the hoatzin intrigued Beebe and posed a challenge to Darwinian taxonomists. In 1868 the famous comparative anatomist Thomas Huxley devoted an entire article to categorizing them. After a detailed comparison of their osteology to that of other birds, Huxley concluded that hoatzin should be classed in an order of their own.

By the time Beebe came face-to-face with the birds in 1908, the scientific community had agreed to class hoatzin within the new order of Opisthocomiformes, of which hoatzin were the only member. While this taxonomic isolation highlighted how hoatzin were different from other living animals, it failed to make any positive assessments of the bird’s evolutionary relationships, essentially marking it as an evolutionary mystery. (Evolutionary biologists still do not agree on how to place hoatzin taxonomically.) What was profound for Beebe in watching hoatzin in Venezuela was the idea that they “defied time and space” with their reptilian crawl and barbed wings. He was convinced that if he could watch the birds long enough and “with sufficient keenness and controlled imagination, some significant hint of avian evolution is certain, sooner or later, to be revealed.” By studying the hoatzin alive, observing what he called their “habits” and what others might call behavior, Beebe hoped to resolve this mystery.

Beebe’s efforts to capture and rear hoatzin did not go well. He could not figure out how to catch them, despite their poor flying abilities. Eventually, he paid local hunters to collect the birds. Even with this assistance, Beebe and his team struggled to find the right diet and housing conditions to sustain the birds in captivity. This resulted in dozens, probably hundreds, of dead birds:

1908

Beebe sees hoatzin for the first time in Venezuela and shoots two of the birds to bring back to New York as research specimens. At Beebe’s request, the director of the Bronx Zoo, William Hornaday, offers a local man $10 for each hoatzin he can ship alive to New York City. None arrive.

1909

Beebe shoots two hoatzin in British Guiana. Twelve others are collected for the zoo, but none make it to New York alive.

1915

The Zoological Society offers Dr. Emilie Snethlage, curator of the Museu Goeldi in Pará in northern Brazil, $25 for each hoatzin shipped north alive. Five are listed on the packing list, but no hoatzin reach New York.

1916

Beebe tries to establish a hoatzin breeding colony at his field station in British Guiana to have birds available for his own behavioral observations and to sell to zoos around the world. With a team of local field guides he manages to capture two birds. Neither lives long enough to breed, let alone be shipped to the zoo.

1920

Local guides in British Guiana collect nine hoatzin and four nests containing young birds and eggs. None of these make it to New York alive.

April 1922

From his field station, Beebe dispatches his assistant John Tee-Van to collect hoatzin in eastern British Guiana. Tee-Van fails to capture any himself and pays a local man $2 each for three living hoatzin caught in a cast net; two make it back to camp alive. Beebe is hopeful the birds will survive the trip to New York and writes to Hornaday: “You know I am not given to prophecy, or to counting my chickens, whether Gallus or Opisthocomus, in advance, but from present appearances it looks as if the N.Y.Z.P. would have the first pair of adult Hoatzins ever kept in captivity.”

May 1922

One of the captive hoatzin dies from “indigestion.” Beebe sends Bertie, another field station assistant, to get six more adult birds and a dozen hoatzin eggs to hatch in an incubator. Beebe assures Hornaday that “we will have Hoatzins (with the accent on the S) in the Park before winter.” Bertie returns to the field station with live hoatzin and seventeen eggs. Beebe ships one hoatzin to New York. This bird dies two days after leaving port.

June 1922

Beebe ships another hoatzin north and writes to Hornaday: “If it dies en route others will follow, a constant barrage until the Zoological Park has a living specimen.” This bird dies soon after leaving British Guiana.

July 1922

Beebe’s assistant Gilbert Broking purchases nine adult hoatzin, six young birds, and five eggs in eastern British Guiana. Seven of the birds die soon after capture.

August 1922

Beebe has eight hoatzin alive at his field station in British Guiana. Hornaday asks Beebe to stop sending the birds north because he thinks they are “hardly worth sending.” Beebe doubles down and proclaims to Hornaday, “If none of the former [hoatzin] get there this time you can write me down Failure with a capital F!” Beebe ships six hoatzin north under the care of assistant Henry Seton. All of the birds die three days out of port.

September 1922

Beebe plans to amass a large collection of potted caladiums for his next attempt at shipping birds north, convinced that the main problem is maintaining an adequate food source.

October 1922

Beebe returns to Venezuela in a last-ditch effort to collect hoatzin. He shoots one but is thwarted by a scourge of biting flies and leaves empty-handed.

1923

A man named H. G. Legge in Trinidad tries to raise hoatzin to ship to Beebe in New York, but to no avail.

In U.S. newspapers, the object of Beebe’s quest was often depicted as laughably grotesque: “Although the hoatzin is called, through the courtesy of ornithologists, a bird, it is to the lay mind a cross between a terrible thing and something awful,” wrote the Chesterfield Advertiser in 1916. “In its natural state it resembles something dragged in by the cat, and its general method of existence is, to put it mildly, squiffy and inefficient.” Other writers played up the hoatzin’s seemingly prehistoric connections, claiming that it was a “direct descendant of the pterodactyl” and frequently referred to it as “the bird with hands.”

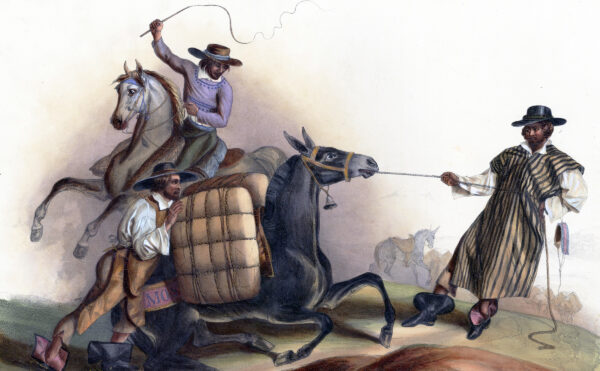

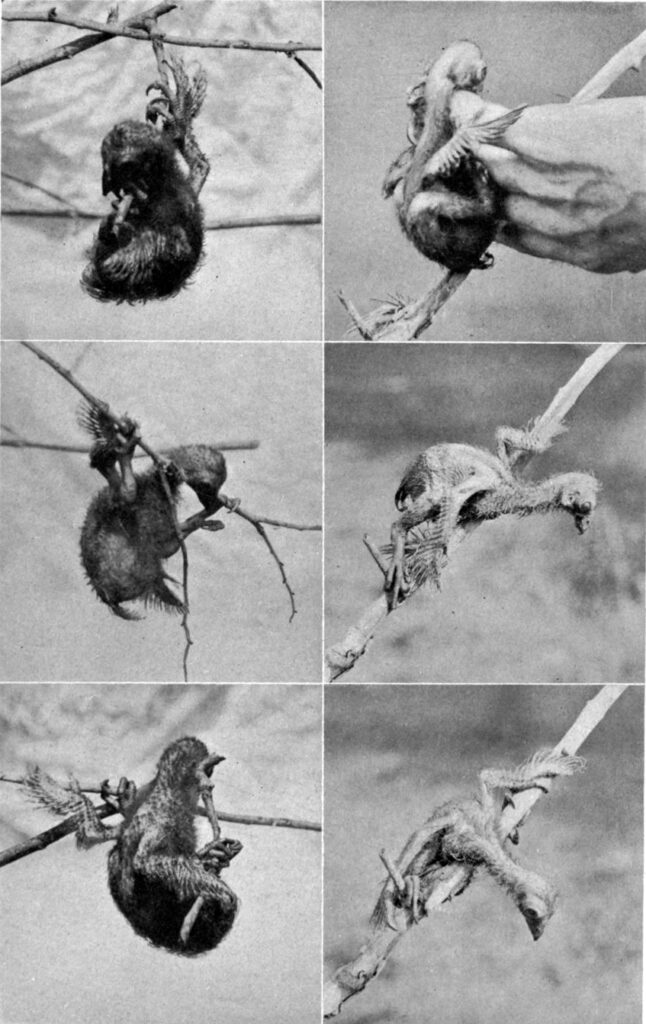

Young hoatzin demonstrating their grasping front claws as they climb, from Tropical Wildlife in British Guiana, 1917.

Biodiversity Heritage Library

Beebe’s failure to keep the hoatzin alive piqued the interest of animal collectors around the world. The Darlingtons, a married couple from Philadelphia who had grown bored of their office jobs, Austrian zoologist Wilhelm Marinelli, and television personality and biologist David Attenborough all ventured to South America in search of Opisthocomus. Multiple expeditions set out from scientific institutions in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Chicago, and London. In 1931 Cecil S. Webb, superintendent of the Dublin Zoo, managed to air-lift one hoatzin from British Guiana to the London Zoo, but it “never thrived and died very emaciated” after four and a half months in captivity. In 1961 J. Lear Grimmer, associate director of the U.S. National Zoo in Washington, D.C., successfully retrieved one bird for his park. Despite Grimmer’s certainty that his wife, Margaret, would be able to “cajole these birds into domesticity,” this bird died within six months of leaving South America.

From Missing Link to Conservation Icon

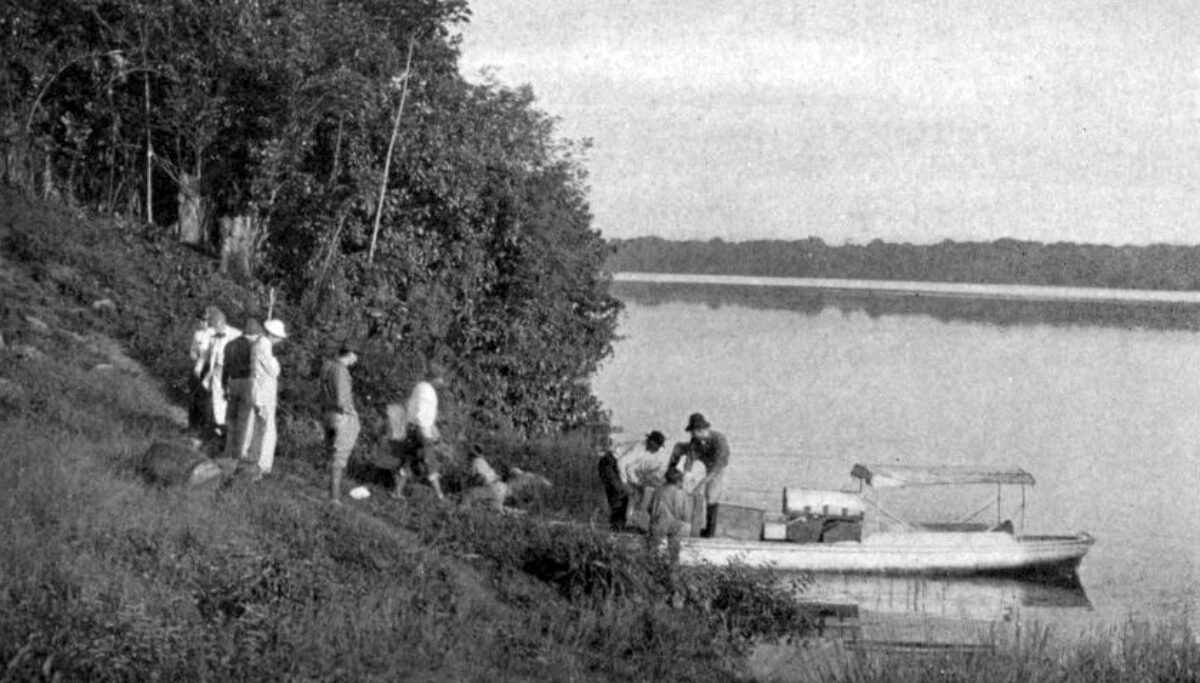

In 1978 the New York Zoological Society once again took up the search for hoatzin. Ignoring the long history of failed attempts to keep these birds in captivity—or perhaps motivated by it—the zoo’s curator of ornithology, Joseph Bell, and members of the zoo’s administration launched a new expedition to Venezuela.

Like Beebe, members of the 1978 expedition struggled to catch hoatzin. Most of the expedition journal entries describe birds that were far more evasive than the team anticipated. Hoatzin nest in branches that overhang water, and hunting teams usually approached them by boat. Once disturbed, the adult birds flew inland to wait out the attack, seated safely on the tangled branches of impenetrable mangroves and thorny bunduri pimpler trees. After a week of fruitless hunting trips, the team packed their gear, expecting to return to New York empty-handed. During their final dinner in Venezuela, a man from a neighboring town arrived with nine adult hoatzin, and brought thirteen more later that evening. The group from the zoo unpacked their supplies and spent the next three weeks trying to sustain the birds on a mixture of chicken mash and bone meal, despite knowing that hoatzin primarily eat leaves. A hand-drawn chart in the team’s shared notebook shows the birds slowly losing weight and dying; once again, none made it to New York alive.

One would think this would have been enough for the Bronx Zoo. Why keep up an expensive and deadly chase for a bird that clearly did not thrive in captivity?

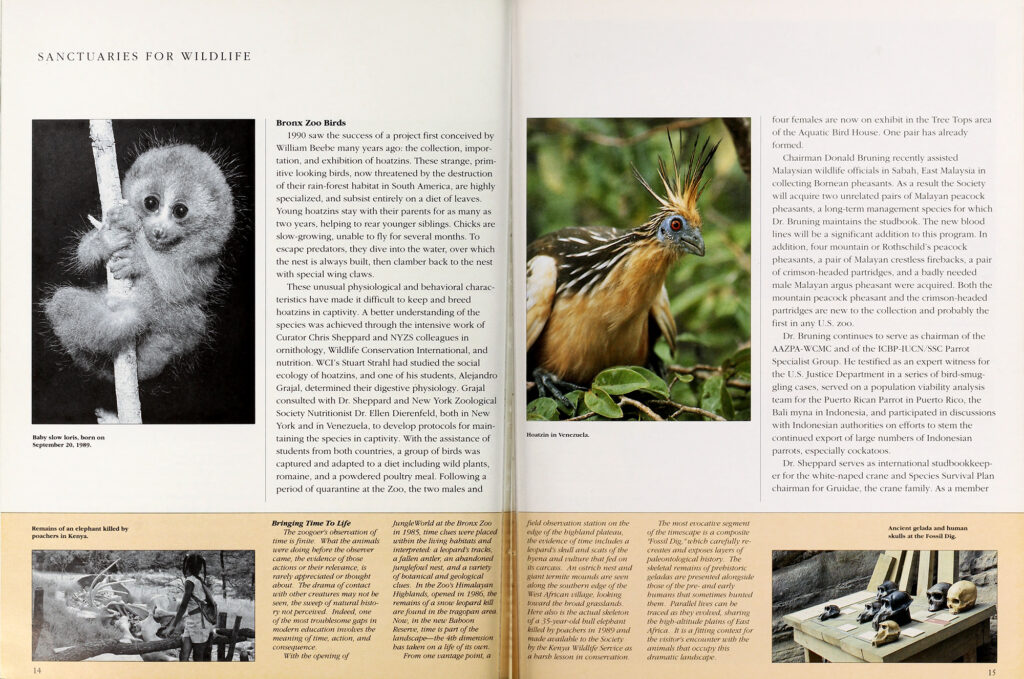

For reasons not explained in Zoological Society literature or existing archives, in the late 1980s the zoo once again embarked on a mission to bring hoatzin to the Bronx. Research scientists speculated that past efforts to keep the birds alive failed because of “nutritional imbalances” and “wide fluctuations in ambient temperature,” and their goal was to formulate a new diet that would sustain the birds in captivity. Once they obtained a number of adult hoatzin, they slowly acclimated them to outdoor aviaries on the grounds of a Venezuelan cattle ranch. The researchers fed the hoatzin two different experimental plant-based mixtures and chemically analyzed the feces of each bird to determine the best combination of lettuce, timothy hay, soybean powder, alfalfa, and vitamin supplements to maintain the flock. In the society’s annual report for 1990, the zoo triumphantly announced that it had finally found “success in a project first conceived by William Beebe” more than 80 years earlier—six adult hoatzin were put on display in the Bronx Zoo’s Aquatic Bird House. Two of the hoatzin lived for at least five years. They produced a clutch of eggs that did not hatch. This short-lived success was seen as a triumph in the field of animal husbandry.

None of the signage associated with the hoatzin exhibit explained the zoo’s fraught journey to collect the birds or how many hoatzin lives were lost in the process. Instead, institutional literature pushed the idea that the birds were threatened in the wild by habitat loss and gave the impression that the zoo was actively conserving them in South America. While it’s true that deforestation in the Amazon is a serious and ongoing problem, wild hoatzin populations were stable, and the Zoological Society had no programs aimed at protecting the birds or their habitat. The hoatzin has been listed as an animal of “least concern” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List since the organization first surveyed the bird’s population in 2000.

When the hoatzin went on display in New York, the Zoological Society was involved in active conservation projects around the globe in cooperation with its sister organization, Wildlife Conservation International. Animal exhibits at the Bronx Zoo were presented as educational outposts of the institution’s international work, with the accompanying claim that education about the existence of relatively unknown animal life was, in itself, a useful component of conservation. It is possible that education about the hoatzin was the zoo’s main goal. Even so, instead of conveying realistic information about the Bronx Zoo’s collecting methods or the lives of the animals they put on display, the message of conservation that accompanied the hoatzin exhibit in the 1990s created an abstract sense of environmental care that hid the details of animal procurement the Zoological Society either did not want people to know or felt was unimportant.

This reframing of the zoo’s hoatzin project fits into what historian Elizabeth Hanson has identified as a broad shift in zoo management that began in the 1960s and 1970s, and that continues today. In response to growing concerns about species loss and habitat destruction, zoos aimed to “convince the public that they were part of the effort to save species rather than contributing to extinctions.” They did this, in part, by presenting captive breeding programs as key components of successful conservation plans. Ostensibly, if the Bronx Zoo could coerce their captive hoatzin to breed, they would be contributing to the longevity of the species. These kinds of breeding programs served the dual purposes of updating the zoo’s reputation as a place of environmental conservation and helping maintain the size of the zoo’s animal population at a time when collecting creatures from the wild was becoming increasingly impossible due to new protective legislation, such as the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and the Animal Welfare Act. With the onset of these regulations, zoos could no longer easily collect animals from the locations they traditionally used as harvest grounds for their most prized exotic fauna, and in-house breeding programs became one of the most efficient ways to maintain steady populations of desired animals.

The Bronx Zoo’s claims to conservation through hoatzin collection were aspirational at best and at worst a revisionist cover for problematic collecting techniques.

Hanson, in her survey of U.S. zoos, points to a larger problem inherent to many captive-breeding programs: while they might increase the number of individuals in a particular species, they often do not account for rapidly shrinking animal habitats in the wild, essentially ensuring that captive populations can never be released. Although the Zoological Society and the Wildlife Conservation Society (the name of the New York Zoological Society since 1993) have been integral in the creation of protected parklands around the globe, for the entirety of the Bronx Zoo’s existence it has worked closely with fossil fuel and other extractionist companies, accepting funding from Standard Oil and, later in the 20th century, ExxonMobil, whose activities have actively contributed to widespread habitat loss around the globe. This relationship is a convenient form of greenwashing for fossil fuel companies that diverts attention away from the environmental destruction caused by extractive industries. In 2015, ExxonMobil announced the discovery of high-quality oil reserves buried beneath the Atlantic waters just north of Guyana. A spill from one of these new wells could threaten not only the hoatzin, but all of the organisms that depend on the aquatic ecosystem in northern South America and the Caribbean Sea. The Wildlife Conservation Society has not intervened or spoken out about the endeavor, despite its stated commitment to the well-being of the birds.

Conservation is a broad term that encompasses a range of very different practices and ideas. The Bronx Zoo’s claims to conservation through hoatzin collection were aspirational at best and at worst a revisionist cover for problematic collecting techniques. The narrative of conservation that was used to elide the zoo’s initial intentions with hoatzin demonstrates the need to question the zoo’s claims of dedication to environmental care as well as the utility of animal breeding to ameliorate the current, potentially existential threat of climate change and habitat loss.

As for Beebe, he was less concerned with hoatzin conservation and more interested in studying the birds for clues about evolution. Although he was exasperated at his inability to bring hoatzin to the zoo alive, publicly he described his project as a success because he was able to film the climbing behavior of hoatzin chicks. He screened this footage at lectures about his work in British Guiana, and integrated the film into an animation entitled “Lizard Bird” that illustrated the evolutionary connections between hoatzin and the prehistoric remains of Archaeopteryx, a fossil thought by some to be the “first bird” in the evolutionary record. Building on the hoatzin’s assumed physical similarities to Archaeopteryx, Beebe attempted to formulate an evolutionary history of winged flight. But without an easily accessible breeding group of hoatzin to work with, he was only able to produce a theoretical paper that argued for the existence of a pre-Jurassic animal he named Tetrapteryx that was evolutionarily situated between ancient lizards and Archaeopteryx. In illustrations commissioned by Beebe, Tetrapteryx is depicted with fully feathered thighs that allowed the hypothetical four-winged reptile to glide through the air from the tops of trees, a developmental stepping stone on the way to bi-winged bird flight.

When hoatzin proved too difficult to work with, he stopped chasing the birds and directed his attention to environments that were truly impossible to bring to New York. In 1925, he launched a floating laboratory to study the Humboldt Current, a major cold water current that flows from Antarctica along the western coast of South America. Soon after, he began the work that would bring him lifelong fame: his deep-sea explorations off the Bermudan coast in a steel ball called the bathysphere. From 1929 to 1935 Beebe and his now well-staffed “Department of Tropical Research” used their field stations in Nonsuch and New Nonsuch, Bermuda, to survey the animal inhabitants of the deep ocean. When this proved prohibitively expensive, he once again returned to the jungles of South America and the Caribbean to set up field stations in Venezuela and Trinidad. Although still an employee of the zoo, he chose to live out the rest of his days at Simla, his station in Trinidad, where he died on June 4, 1962.

Although Beebe’s hoatzin photography and his Tetrapteryx hypothesis didn’t get much attention from the scientific community in his lifetime, a recent fossil discovery has thrust his work into the paleontological limelight. In the early 2000s a small dromaeosaurid dinosaur fossil was discovered in the coastal province of Liaoning, China. Named Microraptor gui, it is estimated to have been about the size of a small turkey and had asymmetrical feathers lining its back legs. It looked, according to one evolutionary biologist, “as if it could have glided straight out of the pages of Beebe’s notebooks.” Scientific reproductions of Microraptor gui’s exterior were based on Beebe’s Tetrapteryx illustrations, and evolutionary biologists have used this reconstruction to reconsider the role of four-winged gliders in the development of bird flight.

Though Beebe was eventually recognized as a pioneer in using the palentological record to understand existing biological conditions, his broad, almost impulsive style of scholarship opened avenues in evolutionary theory still traveled more than a century later. His obsessions, taken far beyond the positions popular in his day, are now described as “prescient,” if overly whimsical. Beebe’s quest for the hoatzin was technically a failure, but it functions as a kind of revelation—exposing the acquistive nature of the early zoo and the problematic, self-serving roots of many conservation claims.