Making Marvels: Science and Splendor at the Courts of Europe

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

November 25, 2019–March 1, 2020

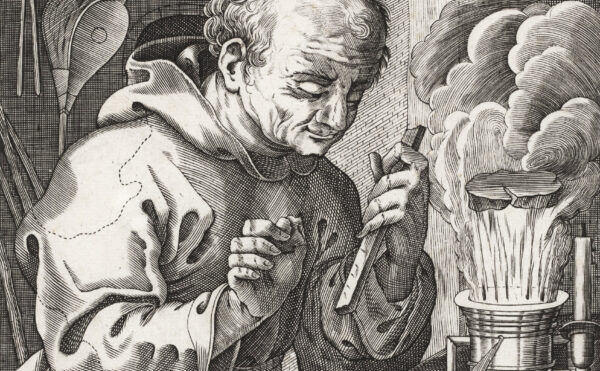

Knowledge is power, especially if that knowledge is scientific, or so believed many Renaissance princes. They demonstrated their scientific power in a number of ways, be it by directly supervising mining operations or installing public clocks and sundials. Through such acts heads of state won respect from the populace for their expertise as well as their wealth and power. Among their peers rulers enhanced their status by studying astronomy, surveying, and alchemy, and by building collections of scientific instruments that measured or modeled aspects of the physical world.

The most precious, highly decorated objects in a prince’s collection were housed in a Kunstkammer—better known as a cabinet of curiosities in the English-speaking world—a storage room for art and precious artifacts, at once a treasury and an exhibition space. The instruments were used for demonstrations, research, and industrial activity, especially metallurgy and mining of ores, such as silver and copper. Such activities enriched the realm and confirmed the prince’s own intelligence and worth. Even though the emperors, kings, tsars, landgraves, and electors of this era owned castles, crown jewels, and libraries, and had households full of liveried retainers, the ownership and public employment of precision scientific instruments remained central to the self-image of many.

That’s the theme of a remarkable new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, Making Marvels: Science and Splendor at the Courts of Europe. Displaying more than 150 items the exhibition illustrates the range of precious artifacts that invoked wonder and signified intellectual and social status. Many of the devices show the integration of art and science and reveal that during the Renaissance the distance between the study and the workshop was often short. One exhibit showcases a handsome mechanical lathe to make intricately shaped cylinders of wood or ivory. A lathe like this was used by Augustus, elector of Saxony, to turn ivory pieces into princely gifts. Not to be missed is a magnificent—and strong—14-foot-long bench for drawing metal wires into finer strands by means of dies and cranks. The bench was also used to produce screws and springs. This wooden machine, made for Augustus, is decorated with marquetry depicting courtly scenes of tournaments and hunting, and its iron parts are engraved and gilded. While similar wire-drawing benches are known from engravings, this is the only Renaissance example to survive.

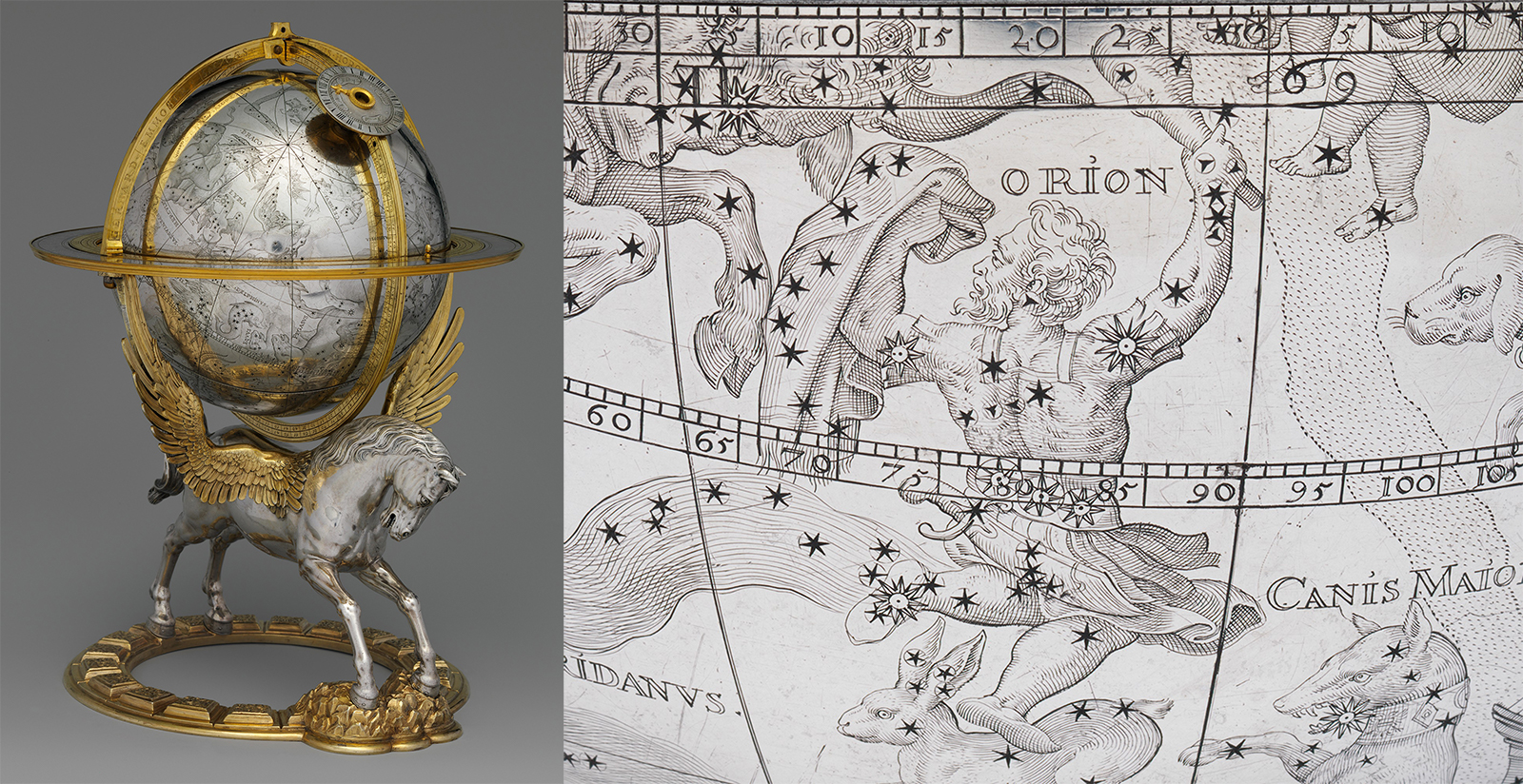

Most princely instruments were beautiful both in design and material. This 1579 silver-and-gold celestial globe, which rotated by means of an internal clockwork mechanism, was made by a clockmaker for Otto Henry, Elector Palatine. The prince directed the clockmaker to collaborate with a mathematician so that the clock’s movements would match actual celestial positions and not be just a generic model like the common armillary spheres. This piece was completed only after Otto Henry’s death and was received by Rudolf II, the Holy Roman emperor, who placed it permanently in the Dresden Kunstkammer. Such elegant showpieces confirmed rulers’ wealth, knowledge, and taste, as well as their engagement with the exact sciences.