One night in 1669 German physician Hennig Brandt attempted to create the philosophers’ stone. This elusive goal had been pursued by alchemists for centuries for good reason: it could transform base metals into gold.

Brandt had spent most of that day in his laboratory, heating a mixture of sand and charcoal with a tar-like substance produced by boiling down about 1,200 gallons of urine over two weeks. He then maintained the mixture at the highest temperature his furnace could reach. After many hours a white vapor formed and condensed into thick drops that gleamed brightly for hours. The glowing, waxy substance had never been seen before. Brandt called it phosphorus, a Latin term for things that give off light.

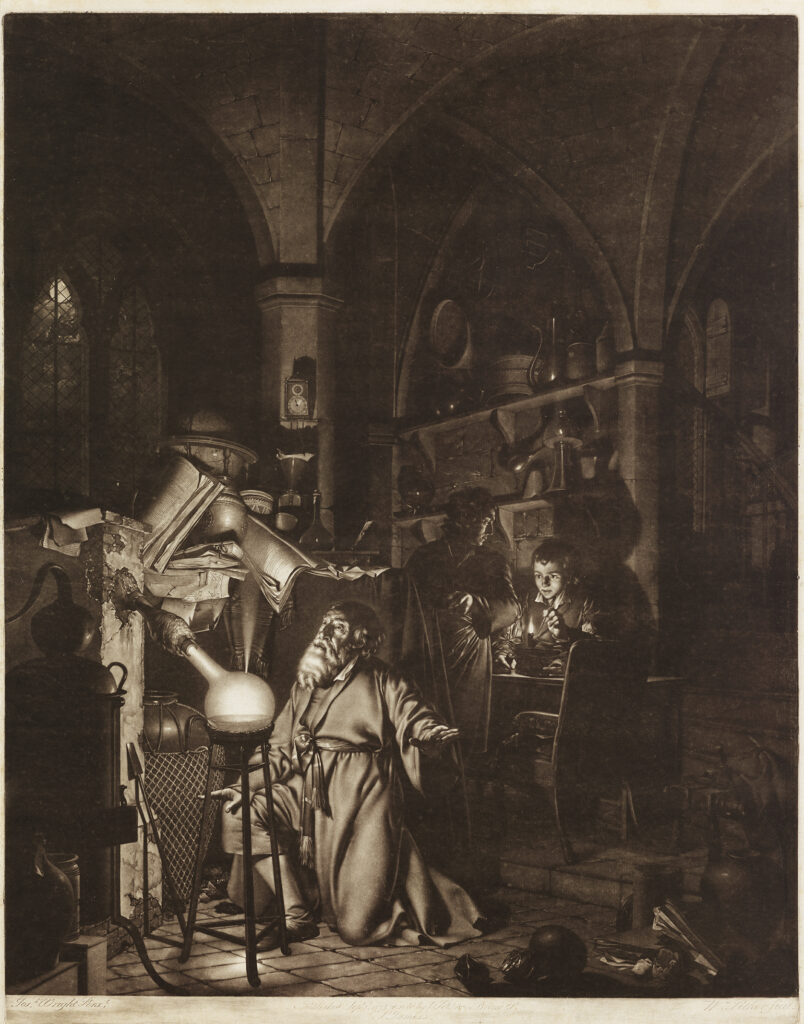

Brandt’s was an era that still saw a world made up of four elements: fire, air, water, and earth. And like the fascinated colleagues to whom he showed his new compound, Brandt assumed it was composed of these elements. (A little more than a hundred years later Antoine Lavoisier replaced this worldview with another, of elements as simple substances that could not be further decomposed.) Whatever his categories, Brandt’s phosphorus was a spectacular sight. Artist Joseph Wright of Derby immortalized this moment a century later in his painting The Alchymist.

Within 50 years of its discovery phosphorus was being produced and sold to apothecaries, natural philosophers, and showmen, who made the element the centerpiece of demonstrations at princely courts and scientific societies. Within 100 years phosphorus was appearing in chemistry textbooks, such as P. J. Macquer’s popular Elements of Theoretical and Practical Chemistry. Within another 50 years the element was making its way into matches, fertilizer, and bombs, once mineral phosphates had replaced urine as the best source material.

Brandt’s name wasn’t prominent in the earliest accounts of the discovery, but Macquer gave him formal credit in his textbook, writing that “the phosphorus here described was first discovered by a citizen of Hamburgh named Brandt, who worked upon urine in search of the Philosopher’s stone.” Macquer understood such transformations to be impossible, but in his unusually sympathetic interpretation he noted that such chemical manipulations “proved the occasion of several curious discoveries.” Wright, who knew Macquer’s book, was inspired by the latter’s understanding that misguided experiments could lead to real discoveries.

The Alchymist (1775) by engraver William Pether, after the 1771 painting by Joseph Wright of Derby.

At about this time Wright was part of an intellectually engaged circle of physicians, scientists, and industrialists in the English Midlands. Their conversations and chemical experiments prompted Wright to re-create Brandt’s historic moment of scientific discovery. Wright’s decision to paint an action portrait of a pioneering chemist was unprecedented. For centuries the genre of history painting had featured saints, military leaders, and royalty; never had such artwork featured a specific physician, alchemist, or philosopher at work.

The 1660s had been a lucky time for Brandt; the 1760s were fortunate for Wright. In his era an artist’s renown depended on high-quality engravings of his paintings. Prints were most people’s only access to art, and printmakers had just recently perfected an entirely new engraving technique called mezzotint. This innovation made it possible for printers to reproduce painterly contrasts from bright whites to rich velvety blacks. William Pether, a leading English engraver, produced spectacularly subtle and nuanced renderings of The Alchymist (painted by Wright in 1771), as well as a dazzling mezzotint of Wright’s Orrery (1766), also in the Science History Institute collection. These engravings are among the very finest of the 18th century.