Deborah Blum. The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Penguin, 2018. 330 pp. $28.

The 12 members of the exclusive Washington, D.C., dining club—young men chosen from among hundreds of applicants—sat in high-backed chairs of dark oak, six to a table, in three-piece suits and ties. The tables were covered in crisp, white linen, though the dining room itself was rather plain with bare, white walls. Membership for the 12 included three square meals a day. For half of them it also came with a side of poison.

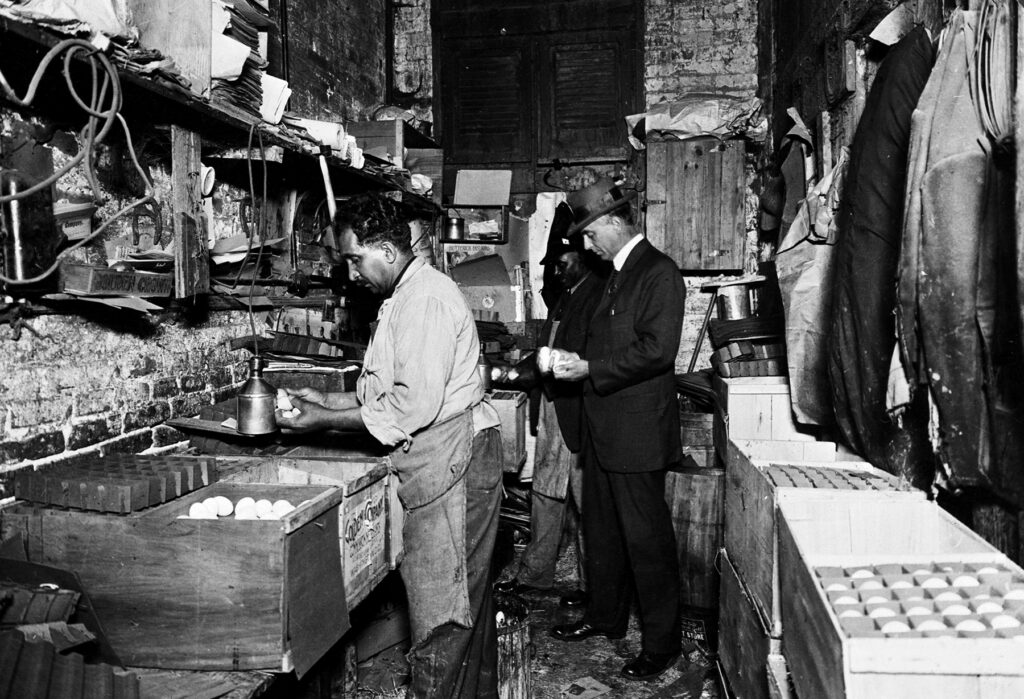

To be fair the poison was carefully administered and monitored. The experiment, which began in 1902, was the brainchild of government chemist Harvey Washington Wiley, who had long been concerned about the newfangled preservatives and colorants being pumped into food. Until Wiley came along, no one had ever bothered to find out what those additives could do to a human being. And if no one knew the effects of a particular additive, passing legislation to protect consumers would be pointless.

Wiley set out to change things, one additive at a time. First up was borax. Today we’re most familiar with borax in cleaning solutions, but it’s also used in enamel glazes, as a pesticide and an antifungal, and as a taxidermy preservative. The preservative properties of borax made it attractive to food producers starting in the 1870s, particularly to those in the meat and butter businesses. Butter producers published studies that suggested the American consumer actually preferred the slightly metallic taste of butter with borax. Surely, said the meat manufacturers, a little borax is better for humans than an accidental mouthful of rancid meat. “I wish to say that every one of us eats embalmed meats, and we know it and we like it,” said the president of a company famous for its borax-based preservative.

Wiley was not convinced, and borax was the first additive put on the table, so to speak, for his volunteers, who had been nicknamed the Poison Squad by the newspapers. Wiley picked borax because it was widely used, and studies had shown it to be relatively but not completely safe. He reasoned that his volunteers stood a good chance of avoiding serious health effects while he figured out the nuts and bolts of the test procedure, which he hoped would serve as a template for future testing. The subjects, however, soon figured out which table had the borax-infused butter and milk and began to avoid those foods. In response Wiley changed the experiment so additives were now delivered by capsule, and diners were carefully watched to make sure they swallowed their dose.

Wiley split the volunteers into two groups and alternated their exposure to borax: one week the first group would eat the capsules; the next week the second group would get the doses. Wiley knew this sort of rotation might not give the clearest results, but he was worried about the health of his volunteers. Thank goodness he was: fully half of his diners dropped out owing to illness before the fifth round, citing pains in the head and stomach. Yes, their dosage had been on the high side, but borax was in so many foods that a voracious eater could certainly ingest that much in a day. Wiley was most worried about the cumulative effects a lifetime of eating borax could have on a person.

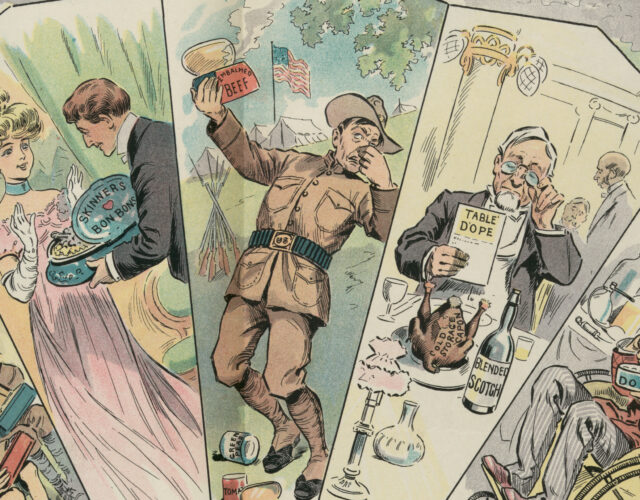

And it wasn’t just borax: it was arsenic and lead brightening the colors in candy. It was formaldehyde preserving milk. It was copper sulfate mimicking the cheery green of French peas. Everywhere Wiley looked, manufacturers were stretching the life of their perishables by questionable means and using adulterants to make products more appealing. They were also stretching the quantity of their goods by adding all kinds of nonsense. Spices frequently contained ground-up coconut shells. Samples of coffee tested by Wiley’s lab contained no coffee at all. “Whiskey” was made from ethyl alcohol diluted with water, tinted brown with tobacco extracts, tincture of iodine, burned sugar, or prune juice. These were affronts to Wiley, who dedicated his life to protecting people from unscrupulous (or simply ignorant) manufacturers.

Deborah Blum’s most recent book, The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, documents Wiley’s remarkable career. Many people may have heard of Wiley’s extraordinary Poison Squad experiments, but far fewer know anything about the man behind those tests.

Wiley was born in 1844 on a farm near Kent, Indiana. Despite a sparse early education, he enrolled in college, but his studies were interrupted by the Civil War and a year spent in the Union Army. After the war he returned to college and eventually went on to medical school. He earned his medical degree but in the process realized caring for the sick was not for him. Instead, he taught chemistry and served as the state chemist of Indiana. He got his first taste of food chemistry while analyzing the sugars and syrups for sale in the state. He found many of these products, such as maple syrup or honey, were adulterated with corn syrup (some were nothing but corn syrup) and other cheap sweeteners.

Wiley’s work on adulteration made him unpopular with the corn industry, but it also made him an attractive hire for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which was looking to replace its chief chemist.

Lured to Washington in 1883, Wiley devoted himself to protecting the health of the American people, whether that meant making sure consumers got what they thought they were buying, investigating additives in food products, or taking up arms against powerful corporate interests. When an unfriendly secretary of agriculture suppressed Wiley’s reports, Wiley figured out other ways to get his findings to the people. He gave lecture after lecture on the hazards lurking in food. For three decades he was a thorn in the side of all sorts of people, including President Theodore Roosevelt. (Teddy had a soft spot for saccharin. Wiley, unsurprisingly, wasn’t a fan of the artificial sweetener and considered the jury out on the matter of its safety.)

With the results from the Poison Squad experiments, Wiley sought a ruling on the safety of a host of additives in American diets. His volunteers ate salicylic acid, sodium sulfite, sodium benzoate, even formaldehyde. The borax results were positively tame compared with what some members of the Poison Squad endured from other additives. Wiley had to stop the sodium sulfite test halfway through, and only 3 of his 12 volunteers made it to the end of the sodium benzoate test. (The sign in front of the dining room was no joke: “None but the brave can eat the fare.”)

The Poison Squad tests and misadventures drew national attention to the need for a federal food and drug law. But not until a million women had written to the White House in support of such a law did Congress get around to passing the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. The food industry had fought tooth and nail to keep government out of their business and had thrown big money at friendly senators and scientists willing to testify that, as Blum puts it, “preservatives were chemically harmless and that because the compounds prevented decay, they also prevented countless Americans” from falling ill from rotten food. Wiley’s tenacity prevailed, but the new law had a big flaw: no clear standards for food. Early drafts of the bill ordered the Department of Agriculture to “establish standards of purity for food products and to determine what are regarded as adulterations therein,” notes Blum. “But the industry-backed National Food Manufacturers Association had successfully lobbied for the removal of that language.” The new law was maddeningly vague; it didn’t name a single toxic compound to be regulated and made enforcement against wrongly labeled or adulterated products cumbersome if not downright impossible. But it was a start, the first of its kind, and it paved the way for the creation of the Food and Drug Administration (of which Wiley became the first commissioner) and the much stronger Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938.

After 30 years at the Department of Agriculture, the constant battles became too much for Wiley. But he wasn’t ready to retire yet: in 1912 Good Housekeeping offered him twice his government salary to become director of a new department of “food, health and sanitation.” As Blum explains, the job spoke to everything Wiley loved:

Wiley relished the freedom of the job and held the position for 18 years, continuing to advise the American public on food safety until just before his death in 1930.

Wiley is a reminder of what a single person can do. His tenacity guided the nation’s food policies and helped make the world a safer place for American consumers, one meal at a time. Except, perhaps, for the members of his Poison Squad.