As the battered, blue Buick pulled up to the church in Santa Fe, a short, tubby man stepped out to meet it. He climbed into the passenger seat and the car took off, winding its way to the edge of town, then up into the mountains.

It was a warm September night in 1945. The two men sat inside the car and talked like old friends, watching the lights of the city below. After a while, as the desert cooled, they headed back to Santa Fe. Just before parting, the thin, bespectacled driver handed his passenger a package. They shook hands warmly and, despite promises to visit, knew they’d probably never see each other again.

After the car rattled off, the tubby man schlepped to the bus station. Maintaining his grip on the packet, he sat on a bench and tried reading a book, Great Expectations. But he couldn’t concentrate. He kept popping up and scanning the crowd, worried he was being followed. He looked jumpy, even paranoid, and with good reason: he was a Soviet spy, and the packet in his hands contained the blueprints for an atomic bomb.

After a bus ride to Albuquerque he caught a plane to Kansas City and a train to Chicago. The train was so crowded he had to sit on his suitcase, but he clutched the papers tight and didn’t complain. After several delays he eventually reached New York—but too late to meet his Soviet contact. The backup meeting wasn’t for two weeks, which meant two more weeks of carrying the packet around, two more weeks of paranoia. For 14 days he never let the package out of his sight, even taking it grocery shopping. Indeed, there was only one place he felt safe during that fortnight—his chemistry lab.

As soon as he got his experiments running, the stress of atomic espionage lifted a little. He could lose himself among the crucibles and test tubes and let his guard down. And when he finally handed off the blueprints, he once again buried himself in lab work to push the matter out of his mind. Some people drink to forget troubles; Harry Gold did chemistry.

Today Gold is best known as a spy and a snitch. He accepted top-secret documents from Manhattan Project physicist Klaus Fuchs and delivered them to Soviet agents. And when the FBI finally caught Gold, his testimony helped land Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in the electric chair. But if anyone had asked Gold what he would call himself, his answer would have been simple. He was a chemist.

A combination of anti-Semitism and economic hardship first pushed Gold into espionage. He grew up in a rough neighborhood in South Philadelphia, where his family suffered discrimination as Jews and immigrants. Gangs threw bricks through people’s windows and beat up the short, slight, bookish boy on the way home from the library.

Gold’s father, Samson, a carpenter at a phonograph factory, had it even worse. His boss hated Jews and once snarled at him, “You son of a bitch, I’m going to make you quit.” He then removed everyone but Samson from the assembly line and forced him to sand down all the wooden cabinets by himself. He had to work at a frantic pace, and Gold remembered him coming home with bleeding fingertips night after night. But the young Gold admired how his old man never complained and never quit.

Some people drink to forget troubles; Harry Gold did chemistry.

Samson was laid off, however, in 1931, which put Gold in a tough position. He’d worked during his teenage years at the local Penn Sugar plant, starting off washing spittoons and glassware before working his way up to lab assistant. He liked the work enough to start taking classes toward a chemistry degree. But when his father lost his job, Gold had to quit school and become the family’s breadwinner. Unfortunately, the Great Depression just kept getting worse, and when Penn Sugar cut Gold loose in December 1932, the family faced the real possibility of losing their home.

After several desperate months Gold’s friend Tom Black found him work at a soap factory in New Jersey for $30 a week, a good wage for the time. Gold was deliriously grateful. But there was a catch. Black was an ardent Communist, and he insisted Gold accompany him to meetings.

Although Gold leaned left politically, the Communists he met disgusted him. He dismissed them as “despicable bohemians who prattled of free love . . . lazy bums who would never work under any economic system . . . polysyllabic windbags.” A few months later, when Penn Sugar rehired Gold, he left Jersey behind and refused to attend any more meetings.

But Black kept hounding Gold, badgering him to join the Communist Party. The Soviet Union, Black explained, needed to build up its industrial base and improve people’s standard of living. But American firms were stingy about licensing technology. Could Gold swipe some trade secrets?

Gold hesitated. Penn Sugar had been good to him—not many firms would have let a spittoon-washer become an assistant chemist—and the company had subsidiaries in several different industries, meaning he could work in almost any field he fancied. But Black’s plea for help moved him. Gold liked the idea of saving the huddled, starving Soviet masses—people like his own family. Soviet agents often appealed to the scientific idealism of people like Gold as well. By liberating trade secrets, they would simply be pooling information, which is crucial to scientific progress.

But what really moved Gold was the fight against anti-Semitism. The Soviet Union, Gold concluded, had outlawed discrimination against Jews; it was the one nation on Earth where Jewish people were truly equal. In reality of course this wasn’t true: the U.S.S.R. was as prone to anti-Semitism as anywhere. But Gold believed otherwise. He could still remember his father’s bleeding fingertips and the gangs smashing windows in South Philly, and he burned to do something “on a much wider and effective scale than . . . smashing an individual anti-Semite in the face.” Supporting the great Soviet experiment was his chance to fight back. As he later grumbled, the Communists “played me very shrewdly.”

So Gold started spying. He’d riffle through file cabinets at work and sneak documents out—occasionally at first but with increasing frequency as the months passed. He’d then spend hours after work, sometimes full nights, copying them line by line. From various subsidiaries, he took papers on lacquers and varnishes, on solvents and detergents and alcohol. He never meant to take so much, but he was always thorough about his work, illicit or not. And every time Black asked for another report, he’d think of the poor Soviet people—people who loved science and hated anti-Semitism—and steel himself to take more. Overall, he remembered, he “looted them pretty completely.”

At first Gold just handed the copies to Black. Eventually, he started running them up to New York himself, a task that seemed thrilling at first but that he grew to loathe. The rendezvous often meant an overnight train ride and hours of wandering around the city to lose potential tails. (He might sit through half a movie, for instance, before ducking out a side exit.) He then might have to wait for Soviet agents in snow or rain. Overall, “it was a dreary, monotonous drudgery,” he recalled, and the need to deceive his family troubled him: “Every time I went on a mission . . . I must have lied to at least five or six people.” But Gold was submissive by nature and made trip after trip.

Clockwise from the top left, May 1935 cover of Der Hammer, a Yiddish-language Communist magazine published in New York, illustration by William Gropper. Communist demonstration in Philadelphia, 1935. A 1920 Russian Communist Party poster celebrating May Day.

Each year got a little more hectic, and Gold was soon near collapse, often working 18- to 20-hour days. In addition to working full time he was taking evening classes at Drexel University, still trying to get that chemistry degree. Some weeks he barely slept, and his weight had ballooned to 185 pounds.

But no matter how ragged he felt, Gold always found time for lab work. One favorite research project involved thermal diffusion, a way of imposing a temperature gradient to separate a mixture; in particular, he wanted to isolate carbon dioxide from waste exhaust to make dry ice. He described himself as a methodical chemist, a plodder rather than a “one-shot genius”: he made “every possible error in the book until, by the tedious process of elimination, only the correct answer remained.” One afternoon he dropped a rack with 22 crucibles and watched a full week’s worth of labor spill onto the floor. “I did not sit down and cry; nor did I go out and get drunk, as much as I wanted to,” he recalled. He simply worked for two days and two nights straight to redo everything.

Gold was on the verge of quitting espionage when, in 1938, the Soviets surprised him. He’d always longed to finish his degree, and his handler suddenly offered to pay for his tuition at Xavier University in Cincinnati. This wasn’t a selfless gesture: the Soviets were developing a spy at an aeronautical installation near Cincinnati, and Gold would be around to courier documents. But he didn’t care: he loved every second of collegiate life, putting in long hours at the lab and cheering rabidly for the Musketeers basketball and football teams. He stayed at Xavier until 1940 and later called his time there some of the happiest years of his life.

The idyll ended on his return to Philadelphia, where Gold—despite his hopes to extricate himself from the Soviets—resumed spying on a regular basis. It’s not clear why he did so. Always a lonely guy, he perhaps enjoyed the companionship and sense of purpose. Or maybe he felt indebted to the Soviets for paying for part of his education. Moreover, world events soon compelled him to keep snooping. After Nazi Germany invaded the U.S.S.R. in 1941, the Soviets were desperate for defense help, including technical expertise. Gold hated the murderous Third Reich and resigned himself to more espionage to help the Soviet Union survive.

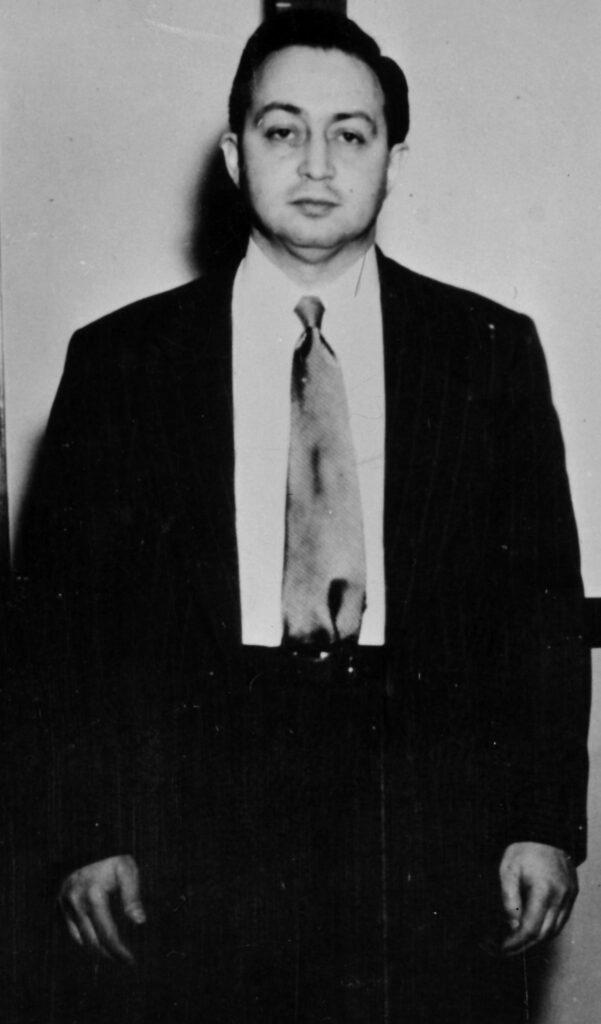

Photograph of Gold presented during the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Martin Sobell.

But the tedium and guilty feelings were as bad as ever, and when Gold found himself waiting for yet another late-night train in New York in the fall of 1942, he finally resolved to cut ties. And he might have—if a drunk at the station hadn’t started harassing him. Gold was 31 years old then, of draft age, but the army had rejected him for having high blood pressure (the navy would soon do the same). So when the souse called him a “yellow draft dodger” and a “kike bastard,” Gold was incensed.

As Gold later said, “I would have smashed him—hard—but I withheld because I could not afford to be involved in a scrape in New York, where I had absolutely no business to be. So I just walked away. But as I did, so went my resolution to quit espionage work. It seemed all the more necessary to . . . work with the most increased vigor possible to strengthen the Soviet Union, for there such incidents could not occur. To fight anti-Semitism here [in the United States] seemed so hopeless.”

Thus resolved, Gold continued spying, albeit with some changes. He shifted away from industrial espionage to more military work. He also took on new roles; he accepted documents and even a sample of explosives from scientists in defense labs and interviewed these contacts for reports. Handling sources was delicate work, requiring both technical know-how and psychological savvy. But Gold excelled: he was what the Soviets might call a “disciplined athlete”—a cool, reliable spy. So when the top scientist in the Soviet spy ranks got transferred from England to New York in late 1943, Gold was the obvious choice to handle him.

On February 5, 1944, just before 4:00 p.m., two men began converging on a vacant lot near a playground on Manhattan’s East Side. One was thin and prim, wearing tweeds and glasses. He was carrying a green book and, despite the winter chill, a tennis ball.

Seeing the ball and book, a short, jowly man—wearing one pair of suede gloves and clutching another—sidled up and asked for directions to Chinatown.

“Chinatown closes at 5 o’clock,” the thin man answered, completing the recognition signal. And with that, Klaus Fuchs and Harry Gold began walking.

Gold introduced himself as “Raymond” and after a short walk hailed a cab. But before long Gold stopped the car and hustled Fuchs into the subway to lose any tails. (There Gold might also have shown Fuchs one of his favorite evasive maneuvers—darting out of the train car just before the doors closed.) The circuitous route eventually landed the duo at a steak house on 3rd Avenue. Gold was proud of his tactics, but Fuchs dismissed them as juvenile. He also scolded Gold for his habit of constantly swiveling his head as they walked, looking for tails. That only attracts attention, he said.

Having laid down the law, Fuchs started talking business. Although German born, he’d been run out of Nazi Germany for Communist activities and had moved to England to work in nuclear physics. He’d recently transferred to New York to work on the Manhattan Project, which he explained to Gold was inching toward a bomb of unprecedented power.

He was what the Soviets might call a “disciplined athlete”—a cool, reliable spy.

After this first meeting several more followed over the next few months—in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, at movie theaters, bars, museums. Every so often Fuchs handed Gold a thick envelope; inside were pages filled with diagrams and mathematical derivations in a tiny, neat script—all top-secret bomb work.

Sometimes the scientists chatted, although each man remembered their conversations differently. Fuchs recalled professionalism—terse exchanges and strict discipline. Gold recalled a budding friendship. In between spy talk they discussed chess and classical music, and Fuchs opened up about his family, including a sister in Massachusetts. Gold in turn told Fuchs about his twin children and his wife, a redhead who had modeled for a department store. This was a complete fabrication—the fantasy of a lonely man.

Gold also tried impressing Fuchs with his scientific knowledge. It didn’t go well. During one meeting Fuchs admitted that his team was having trouble separating uranium isotopes, the first step in building a bomb core. Gold jumped in and suggested they try thermal diffusion, the process he’d been tinkering with at work. Fuchs dismissed the idea as amateurish, which stung Gold. (Unbeknownst to Fuchs the Manhattan Project had in fact just opened a thermal diffusion plant; without it there would have been no uranium bomb in 1945.)

In July 1944 the pair had their eighth meeting scheduled, near the Brooklyn Museum. Fuchs didn’t show. This worried Gold, given how precise Fuchs always was, but they had a backup meeting scheduled a few days later near Central Park. So Gold took off.

Fuchs missed the next meeting, too. Thoughts of muggers flashed through Gold’s head, and he returned to Philadelphia distraught. An invaluable spy—and a man he considered his good friend—had suddenly gone AWOL.

He needn’t have worried. Fuchs was fine—better than fine. Through a combination of luck and lax security, this top Soviet spy had just wrangled an invitation to the inner sanctum of the Manhattan Project—the weapons lab at Los Alamos.

Neither Gold nor the Soviets knew where Fuchs was, but after months of searching Gold finally tracked down his friend through Fuchs’s sister in Massachusetts. The two spies agreed to meet in Santa Fe on Saturday, June 2, 1945.

Just before the trip Gold met his Soviet handler at a bar to iron out the details. The handler ordered Gold to take a roundabout journey by train and bus, with stops in California, Colorado, and Texas, to avoid possible surveillance. But for once Gold stood up for himself. He had already borrowed $500 from Penn Sugar to finance the New Mexico trip and couldn’t afford to take more time off. He insisted on traveling there directly.

But if Gold won that argument, he would lose a second, more important one that day. After wrapping up the details of the Fuchs meeting, the handler told Gold something surprising: the Soviets had a second mole inside Los Alamos. This mole would be in Albuquerque, not far from Santa Fe, while Gold was visiting, so Gold needed to make a side trip there to pick up additional papers.

In any normal business this request would be reasonable. In espionage it was anathema, a huge security risk for everyone involved. So Gold, feeling his oats, stood up for himself again: “I . . . got up on my hind legs and almost flatly refused,” he later remembered.

This time his handler slapped him down. “I have been guiding you idiots through every step!” he snarled. “You don’t realize how important this mission to Albuquerque is.”

As the tirade continued, Gold backed down and submitted as usual. His handler finally gave him an address in Albuquerque and a last name, Greenglass. The handler then gave Gold half a Jell-O box top, which had been cut into a jigsaw shape. He passed the puzzle piece over to Gold. You’ll know it’s Greenglass, he said, because he’ll have the other half.

Gold’s bus pulled into Santa Fe on Saturday, June 2, at 2:30 p.m. With 90 minutes to kill he grabbed a map from a local museum and wandered along the nearby river. It looked pitiful, he thought, smaller than most creeks back home.

Fuchs arrived late in his sputtering Buick. They drove to a deserted road and took a short walk together. Fuchs discussed his work on the new plutonium bomb but assured Gold, wrongly, that the war would be over before it was ready for use against the Japanese. He then handed Gold a packet, and they parted. All in all a good meeting.

The second meeting proved different. Gold took a bus to Albuquerque, arriving around 8:00 p.m., and went straight to the address on the onionskin paper, 209 High Street. He felt nervous holding documents from Fuchs and wanted to skip town soon. But David Greenglass wasn’t home.

Gold struggled to find lodging in a town packed during the weekend with servicemen and workers from the nearby military installations. (Ironically enough, it was a policeman who directed the atomic spy to a private boardinghouse.) After a wretched night on a cot in a hallway there, Gold returned to Greenglass’s home the next morning and trudged up the narrow staircase. He knocked on the door at the top, and when it opened, he almost fell right back down in shock. The man who answered was wearing army trousers. Gold had no idea that members of the U.S. military had been dragged into this.

Composing himself, Gold asked if he was Greenglass. Greenglass said yes. “I come from Julius,” Gold responded.

The Jell-O box used by Gold and David Greenglass.

“Oh,” Greenglass said and turned to retrieve a Jell-O box top from his wife’s purse. Gold held out his half, and the pieces matched. Gold then asked if Greenglass had any materials ready. Greenglass said no, that he hadn’t gotten around to it and Gold should come back that afternoon.

Grumbling, Gold found some breakfast and waited. When he returned, he and Greenglass took a walk in the summer sun and made the handoff. The packet included diagrams of high-explosive lenses, one of the most crucial aspects of the plutonium bomb.

Gold caught a train that evening and spent the next two days rattling east, glad to have escaped. But his side trip to Albuquerque would prove costly. It just so happened that David Greenglass had a sister in New York named Ethel, who was married to a man named Julius Rosenberg.

Gold visited Santa Fe again in September. World War II was over, but the Soviets were ramping up for the Cold War. Fuchs delivered one last packet to Gold before returning to England; it contained data on the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, as well as technical details about making bombs. This was the trip where Gold missed his contact in New York, forcing him to spend two weeks carrying the papers around. The fortnight exhausted him, and given the expense and added stress of trips to New Mexico, he decided yet again he was done with espionage.

Espionage, however, wasn’t done with him. In 1946 Penn Sugar laid Gold off again. He applied to the KGB for funds to open a thermal diffusion lab, and when they turned him down, Gold went to work for a fellow chemist—and fellow Communist spy—in New York named Abe Brothman. It was a huge mistake. Gold’s handlers had warned him the FBI had its eye on Brothman, but Gold either forgot this fact or ignored it. Sure enough, Brothman soon ran afoul of the FBI and implicated Gold in espionage. The two were summoned to testify before a grand jury in July 1947.

A weary Brothman had been threatening in private to confess his role in the Soviet spy machine, but he pulled himself together on the stand and denied everything. Nine days later came Gold’s turn to testify. The night before, Gold swung by Brothman’s apartment, and they went for a drive. Gold wanted to discuss his testimony, but every time he brought the topic up Brothman started ranting about the impending death of capitalism. Appalled, Gold stopped to eat some watermelon with Brothman and finally gave up at 4:00 a.m.

He needn’t have worried: Gold proved every bit as deft at lying under oath as Brothman had, making himself look like a bumbling, absent-minded chemist. And while the FBI didn’t believe either man, it couldn’t poke any holes in their stories, and both of them walked.

Still, thanks to Brothman, the FBI now had a file on Gold. And agents in England were about to reel in a spy who had much more incriminating material on him—none other than Klaus Fuchs.

Brothman paid Gold erratically if at all. (“When there was no money, I was a partner,” Gold said of his time there. “When there was money, I became an employee.”) So in mid-1948 Gold quit and took a job in the Heart Station at Philadelphia’s General Hospital. Not only was he doing good, solid chemistry—he studied electrolyte levels in the blood and how potassium affected muscle function—he was saving people’s lives and would go on to earn a promotion to chief research chemist. He even met the love of his life there, biochemist Mary Lanning. “I had never been happier . . . in my life,” he later said.

Over the next year or so Gold proposed to Lanning twice. She always said no—but not because she didn’t love him. Rather, she sensed a “lack of ardor” on his part—which stemmed from Gold’s fear of exposure as a spy. But he simply couldn’t bring himself to tell her the truth. When he accidentally mentioned Santa Fe once, he then had to cover his tracks by saying Penn Sugar had sent him down to check out a Coca-Cola plant nearby—obvious baloney. They finally broke things off, Gold fearing that if they married and he got exposed, it would ruin her life.

He was right to worry. In September 1949, four years after his last meeting with Fuchs, Gold answered the door at the house he shared with his father and brother and found a Soviet agent there. He tried to slam the door, but the agent quickly said the code words, so Gold let him in. Desperate to be rid of the man—Gold’s family still had no idea he was a spy—he agreed to visit New York two weeks later. They rendezvoused during a downpour, and the agent, to Gold’s horror, urged Gold to defect to Eastern Europe. He refused to explain why.

Clockwise from the top left, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg leaving court after being convicted of espionage on March 29, 1951. Klaus Fuchs after his release from an English prison on June 6, 1959; he immediately defected to East Germany. David Greenglass’s mugshot, undated. Harry Gold testifying at a Senate hearing investigating American spying for the Soviet Union, April 26, 1956.

Everything became clear a few months later. On February 2, 1950, Klaus Fuchs was arrested in England. The United States was still reeling from the news that the Soviet Union had detonated a nuclear bomb the previous August, and the capture of an atomic spy made headlines worldwide. Fuchs confessed he had an American contact named “Raymond.”

Reading this, Gold panicked and decided that, if caught, he would kill himself with sleeping pills. But his old friend Tom Black, who’d first pushed him into espionage, talked him out of it.

Meanwhile, the FBI began what one agent called a “raging monster of a quest” to find Raymond. The bureau investigated 1,500 suspects, with 12 agents working full time and 60 more working part time. Because they knew Raymond had a background in chemistry, they requested information on 75,000 combustible material permits issued in New York City in 1945. They even sent agents to bus stations across New Mexico to ask employees if they remembered a husky white fellow back in 1945 holding an envelope.

The FBI finally caught a break when agents (illegally) broke into Abe Brothman’s lab in New York and found several papers Gold had written on thermal diffusion. This discovery excited them because Fuchs had worked in gaseous diffusion for the Manhattan Project. In truth the two processes have nothing in common, but apparently the FBI didn’t quite grasp that. (Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than smart.) They cracked open Gold’s old case file and, using this and other clues, linked him to Raymond.

On May 15 two agents in Philadelphia paid a visit to Gold at his lab. He agreed to accompany them downtown to answer questions. He never cracked but was so rattled by the visit he had to put in several hours in the lab to calm himself.

Feeling he had no choice, Gold submitted to more hours of interrogation that weekend. When they asked him if he’d visited New Mexico during the war, he denied ever being west of the Mississippi. When they put a picture of Fuchs before him, he admitted recognizing the spy—but only from magazines. Rashly, he also agreed to “settle the matter” by letting the FBI search his home—but only on Monday, when his brother and father were absent. The agents couldn’t have been happy with this arrangement; it would give Gold the chance to purge anything incriminating. But lacking a warrant they agreed to the delay.

Incredibly, though, Gold didn’t purge a thing. He headed to the lab instead. He had a few experiments running, on ways to detect potassium, and couldn’t bear to leave them unfinished. He then had one last evening with his brother and father on Sunday—“to salvage a few more precious hours” of normalcy, as he put it.

Only at 5:00 a.m. on Monday did he begin the purge. Digging through his room, Gold found a letter from a Soviet agent, a plane ticket stub, and a draft report. He scrambled to flush some items down the toilet and buried others in the rubbish bin in the cellar.

He’d just finished when two FBI agents knocked around 8:45 a.m. Wearing pajamas, Gold led them up to his room, which they began to ransack, pawing through drawers and pulling books off shelves. Still a “disciplined athlete,” Gold watched them and chatted.

A little after 10:00 a.m. one agent pulled down a favorite book of Gold’s—a well-thumbed copy of Principles of Chemical Engineering. But of all the books he owned, this one would betray him. As the agent opened it, a tan street map slipped out titled “New Mexico, Land of Enchantment.” Gold had grabbed it at the museum before his meeting with Fuchs.

The agent picked up the map. “So you were never west of the Mississippi.”

Gold all but collapsed into a chair. He asked for a minute to think, then bummed a cigarette, which he normally hated. Even at this point Gold probably could have walked. The FBI had no hard evidence, and it seemed unlikely that Fuchs would turn stool pigeon. But after a decade and a half of espionage, he was simply too tired—tired of lying, tired of running, tired of the burden. All he could think about was how to break the news to his brother and father.

He finally turned to the agents. “I am the man to whom Klaus Fuchs gave the information.”

After a decade and a half of espionage, he was simply too tired—tired of lying, tired of running, tired of the burden.

On his arrest Gold vowed he’d never rat out anyone else. I’ll accept my punishment, he thought, and stay quiet. Then his brother visited him. “How could you have been such a jerk?” he asked. At that moment, Gold remembered, “a good half of that mountainous mental barrier that I had erected against squealing went crashing down.”

Even more wrenching, Gold’s father came to visit later. His old man had always been so proud of Harry—his smart son, the chemist, the one who’d gotten them through the Depression. Now he was weeping, looking frail and bewildered. “This won’t affect your job at the Heart Station, will it?” he asked.

The question broke Gold’s heart. “Down went another section of the mountain.”

Gold pled guilty and spilled everything he knew without even asking for a plea deal. He wrote up a 123-page document detailing his spy work and submitted to endless hours of questions. One agent compared interviewing Gold to “squeezing a lemon—there was always a drop or two left.” And having finally unburdened himself, his health bounced back and his blood pressure dropped and he quickly lost dozens of pounds.

The FBI opened 49 separate espionage cases based on Gold’s testimony. But history remembers one of them above all—the Rosenberg case. Gold couldn’t recall the name of David Greenglass, Ethel Rosenberg’s brother, but he did remember Greenglass’s wife’s name might have been Ruth and a description of their street in Albuquerque. Greenglass’s furlough also coincided with the time frame Gold provided for their rendezvous. When caught, Greenglass confessed everything and claimed he’d been pushed into espionage by Ethel and her husband, Julius.

Greenglass ultimately doomed the Rosenbergs to the electric chair, and he was savaged for turning against his own sister. But Gold’s reputation took a beating, too, from all sides of the political spectrum. Communists smeared him as a “pathological liar” and lonely “weakling” who made himself seem more important by inventing fabulous tales. Anti-Communists, meanwhile, condemned him as a stooge who’d betrayed his country. With no plea deal in place the prosecutors at Gold’s trial demanded he serve 25 years in jail. The judge gave him 30. When Gold arrived at Lewisburg Penitentiary in central Pennsylvania, his fellow inmates made their scorn obvious as well. Thieves, rapists, hitmen—they enjoyed respect at Lewisburg. But when Gold the stool pigeon strolled over to play some pick-up basketball one day, every last player walked off the court.

Once again chemistry proved Gold’s refuge. Lewisburg had an unusual prisoner health program that combined medical care for inmates with biomedical research. Gold jumped at the chance to return to the lab and even took shifts in the nearby sick ward to nurse fellow inmates back to health, which went a long way toward rehabilitating him in their eyes. He also spearheaded new research. He studied diabetes and thyroid disease at Lewisburg and even volunteered to be injected with hepatitis-laced blood to help investigate a vaccine. As his crowning achievement, in 1960 he earned a U.S. patent, from prison, on a speedy blood-sugar test using indigo disulfonate.

Gold leaving federal prison after being paroled, May 18, 1966.

This lab work established Gold as a model inmate, and in April 1966, after serving 16 years, he earned parole. On the day of his release his lawyer came to pick him up and was terrified to hear an uproar inside. It sounded like a riot. But it was just Gold’s fellow prisoners, cheering. After his years of selfless dedication they were giving him a roaring sendoff.

On his release Gold settled into a quiet life doing hematology and microbiology in another Philadelphia hospital. (He’d spent the last several months of his sentence studying lab textbooks in his cell at night to catch up on new techniques since his arrest.) He also began mentoring young scientists there, a kindly uncle figure. The only time the façade cracked was when someone mentioned the Rosenberg case. Once, during a news broadcast, a picture of David Greenglass flashed onto the screen. To his coworkers’ shock Gold erupted and screamed at them to turn it off.

Eventually Gold’s heart grew weak, a congenital effect possibly exacerbated by the hepatitis from the tainted blood he’d received in prison. In August 1972 he underwent a risky valve-replacement surgery and died on the operating table at age 61. People in his lab cried when they heard the news.

Gold had once hoped to make a name for himself after prison as a scientist: “Sometime in the future I shall be able to make far greater amends than I have done to date. And this restitution shall not consist in informing and giving evidence to the FBI . . . [but] in the field of medical research.”

It was another fantasy. Gold is still vastly better known for espionage than chemistry: he simply betrayed too many secrets and too many people. But unlike most Communist spies Gold had higher ideals than politics. Deep down he was a chemist first and last—a man who preferred finishing experiments to saving his own neck, even with the FBI hot on his trail. History will probably never rehabilitate his reputation, but other scientists can at least nod along at Gold’s story—his passion for lab work, his meticulousness, the sheer delight he took in chemistry—and say, truly, he was one of us. It was all Harry Gold ever wanted.