In the unfinished basement of a suburban Pittsburgh home, a group of hackers gathered around a workbench. The group, known as Grindhouse Wetware, mostly consisted of young adults sporting tattoos and facial piercings. They fiddled with dissected computers, glue guns, and pliers as they tried to piece together an electronic device the size of a pack of cigarettes. Realizing that they were running out of parts, a pair of hackers made a late-night foray to the local RadioShack and filled a bag with circuit boards, jumper wires, and resistors. A few months later the completed device was bulging out of the forearm of one of the group’s founding members, Tim Cannon.

These hackers are not the type you might expect to find solving computer problems or monkeying with elections; instead, they call themselves “biohackers” because they are trying to modify and improve the human body with technology. Although they believe humans may someday upload our minds to computers or merge our bodies with robotic limbs and organs, they are not content with waiting for that future. To speed up the timeline, biohackers have transformed themselves into cyborg guinea pigs and turned to tattoo artists and body piercers to install technology into their bodies, which is how Cannon received his implant in 2013.

Cannon’s implant consisted of a tiny computer capable of reading his temperature and blood pressure. It sent information to his phone using Bluetooth and was powered wirelessly through a process called inductive charging. Not long after he put it in, Cannon had the implant removed; it was just an experiment to test if it was possible to live with an electronic device beneath his skin without dying from an infection or toxic battery leakage. By that metric the test was successful. Today, Grindhouse Wetware is still working on a smaller, safer version. When they are finished, they plan to make the blueprints freely available to anyone who wants to replicate their work.

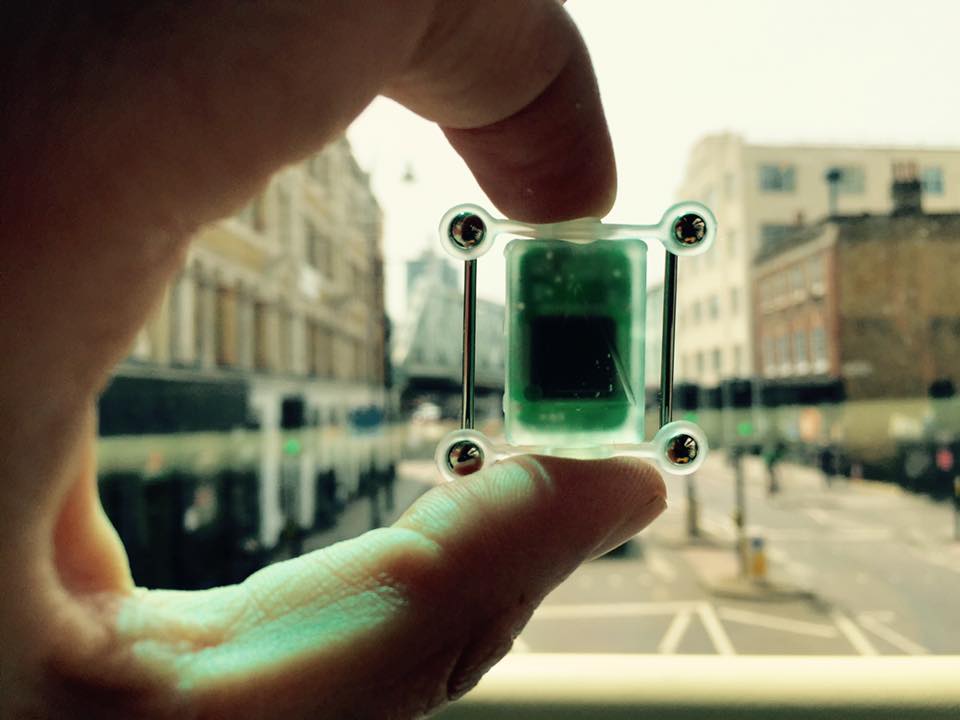

While the Grindhouse hackers prod the physical limits of human-computer modification, a different group of hackers is trying to take these inventions mainstream. Cyborg Nest recently began selling an electronic compass designed to mount on the owner’s chest by means of metal rods. While the compass is attached to you, it subtly vibrates whenever you face magnetic north. They call it the North Sense and claim that it gives the wearer a sixth sense on top of the traditional five.

Of course, wearing a vibrating compass won’t let you “see” north the way some species of birds can. The pathways from our brains are set up in specific ways to interact with the nerves in our skin, eyes, mouth, ears, and nose. But over enough time, if the compass vibrates each time you turn north, your brain might be retrained to respond to that direction in new, unpredictable ways.

Scott Cohen, a member of Cyborg Nest, tried to describe (and, perhaps, sell) how this reprogramming might work two weeks after implanting himself with the North Sense:

“My relationship to space has changed overnight. When I walk into a room full of people I suddenly realise that I am aware of the room in ways that they are not. I am not the same as them anymore. They don’t see what I see. My sensory palette has a new colour and it is called North.”

When Cyborg Nest announced that anyone would be able to order the North Sense, including those outside the traditional hacker community, many biohackers were unhappy. They accused Cyborg Nest of selling out, a recrimination many thought was justified when the device went on sale for $425. Some were dismayed that this uninspired device was the product that would represent the biohacking community to the outside world. As one member of a popular online forum scoffed, “I’ll make you one in no time because it’s simple as [expletive] to do. If they charge more than $80 bucks [sic] for this you are getting ripped off from a hardware stand point [sic].”

Another added, “I mean it’s a kind of [a] cool product but it’s not much more complicated than a vibrating nipple ring. I guess that’s a problem in this community. We are so focused on making truly game changing projects that we omit really basic stuff. . . . I guess if we want money we should strive lower?”

Another commenter pointed out that this device might not even count as true biohacking because it is held in place by metal piercings on top of the chest, not embedded under the skin.

That last point brings up an existential question that the entire community is still grappling with: what can biohackers do with implants that can’t already be done with existing wearable technology?

Most of us have a cellphone with built-in GPS, maps, and even a compass app. Smartwatches allow easy access to maps, messages, and photos on your wrist. Microsoft’s HoloLens, an augmented-reality device kind of like the discontinued Google Glass project, essentially overlays the real world with holograms and is far more practical than replacing your eyeball with a camera.

Many biohackers, including the members of the Grindhouse Wetware collective, believe they have tapped into at least one thing that can’t be replicated with a cellphone: magnetic implants that detect electromagnetic fields. These hackers have surgically embedded tiny magnets into their fingertips. When they wave their hand near a microwave or computer, the magnets spin around and vibrate in the bed of scar tissue that forms around them. Biohackers claim that their brains get reprogrammed to sense and understand electromagnetic fields in ways that nonhackers can never experience. The practical uses of such an ability, they argue, include being able to sense if it is safe to touch an electrical wire, or knowing whether a device is powered on or off without looking at it. So far, though, finger-magnets get put to use most often as party tricks.

Maybe this electronic body modification is the very beginning of a revolutionary new field. Perhaps our grandchildren will walk around with USB ports in their skulls and robotic third arms. But I feel like I could become a cyborg right now if I put on a virtual-reality headset, slipped a smartwatch onto my wrist, and dropped a cellphone into my pocket. No biohacking necessary.

Take a deeper dive into the world of biohacking in this Distillations podcast.