In the late 1950s a group of weary parents in Washington, D.C., came together to solve a vexing problem: how could they score a night out on the town?

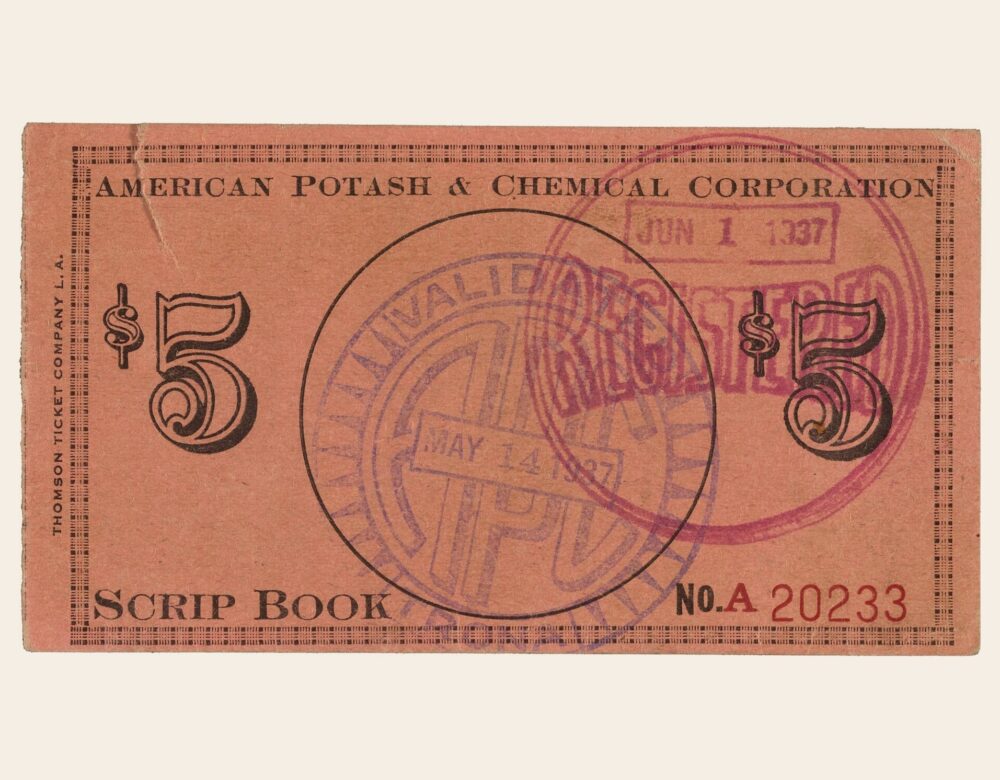

Their solution was the Capitol Hill Babysitting Cooperative, whose members would trade child-tending duties. The idea was a hit, but as the co-op’s ranks grew, the group needed a better way to track who was owed what. The parents eventually landed on a scrip system. One piece of scrip provided 30 minutes of babysitting services for a family. When that family took its turn to babysit, it would receive scrip.

Unfortunately, some families started hoarding their scrip. As movement of scrip slowed down, there were fewer transactions, which only made the hoarding problem grow worse—a classic liquidity crisis. The result was an economic downturn in the babysitting economy—people stopped going out on dates. To fix the problem the group issued more scrip, more than this mini-economy could handle, thus setting off an inflationary crisis in which babysitters were hard to find.

In 1977 former co-op members Joan and Richard Sweeney, the latter a U.S. Treasury official, published a witty commentary casting the babysitters’ yo-yoing economy as an allegory for the inflationary jolts the country was experiencing at the time.

Columnist Paul Krugman was struck by the Sweeneys’ article and has used the co-op’s example repeatedly to console readers during times of economic heartburn. “Its story tells you more about what economic slumps are and why they happen than you will get from reading . . . a year’s worth of Wall Street Journal editorials,” Krugman declared in 1998.

The story is powerful, Krugman explained, because the co-op’s currency crises were real. Scrip-based economies, no matter how small, are real economies.

Creating currency has never been the sole territory of central governments. Time and again companies and communities have established their own currencies. Such scrip is often relied on during difficult times and in disconnected places, when government-issued notes are hard to access or plummet in value. The largest issue of scrip in U.S. history occurred during the country’s greatest economic disaster—the Great Depression. Through fits of bank runs and money hoarding, scrip has helped keep local economies in motion.

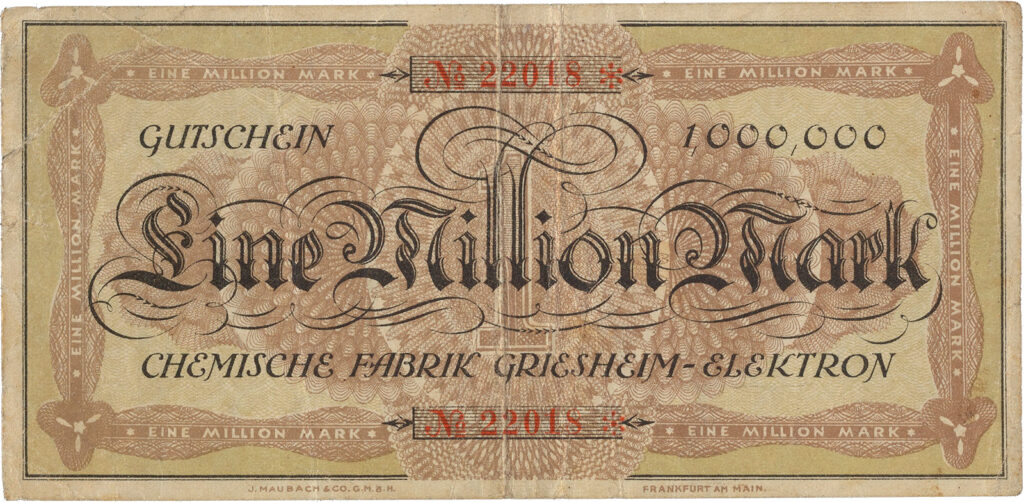

In 1923 Germany’s economy was in freefall. The country still had wealth, but its money was next to worthless. This hyperinflation was the result of the punitive reparations imposed on Germany following World War I. The only way the country could pay the huge sum demanded, the equivalent of about $269 billion today, was to print money, thus devaluing the currency. At one point that year a single American dollar was worth a trillion German marks. As the mark lost value, Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron, maker of fertilizer and lye, was one of many chemical companies that issued scrip to pay its employees, who then used it to buy goods at its company store.

The scrip system reappeared in Germany during even darker times. At Poland’s Łódź ghetto, the Nazis forced arrivals to exchange their money for scrip and ration coupons that could only be used in the ghetto. The result was a transfer of any remaining wealth from prisoners to their oppressors. The scrip system made escape even more difficult and made buying food and medicine on the black market almost impossible. The result was widespread starvation and sickness. In summer 1944 those who had survived the ghetto were sent to Auschwitz.

Wars can also bring about currencies that blur the line between scrip and legal tender. During the American Civil War, uncertainty drove Northerners and Southerners alike to hoard coins for their metal value.

The cash-strapped Union abandoned the gold standard in late 1861 and stopped minting new coins, switching instead to emergency notes known as greenbacks. The move meant people could not be certain banks would exchange their notes for gold and silver, which spurred speculation in coinage and drove down the value of paper notes. The availability of coins, particularly in the East, dried up. Merchants resorted to using stamps to make change, but the flimsy and sticky bits of paper were a poor substitute. In response, the government printed “postage currency” notes with images of stamps in denominations of 5, 10, 25, and 50 cents. (The government abandoned the stamp images in later iterations.) These fractional notes were not officially legal tender but worked as such and remained in circulation into the late 1870s.

The Confederacy never minted currency backed by gold and silver reserves. Instead the Confederate government, along with individual states and banks, issued bills of credit to be paid if the South won the war. As the tide turned against the Confederates, confidence in these “graybacks” cratered; inflation spiked, and prices increased by as much as 9,000%. By the end of the war a cake of soap could cost as much as 50 Confederate dollars. And if the newly clean shopper desired a fresh suit, he could easily spend 2,000 dollars or more.

While war often destroys the value of a currency, it can also drive a government to deliberately do so. On January 10, 1942, the United States government recalled almost all the printed currency in Hawaii. But the territory wasn’t left moneyless. Hawaiians could change their cash for new notes that were identical to the old ones in every way but one—they had the word Hawaii printed on them. Those notes could easily be declared null and void if Japan succeeded in occupying the islands, as military planners feared. Real money instantly made worthless to residents and occupiers alike.

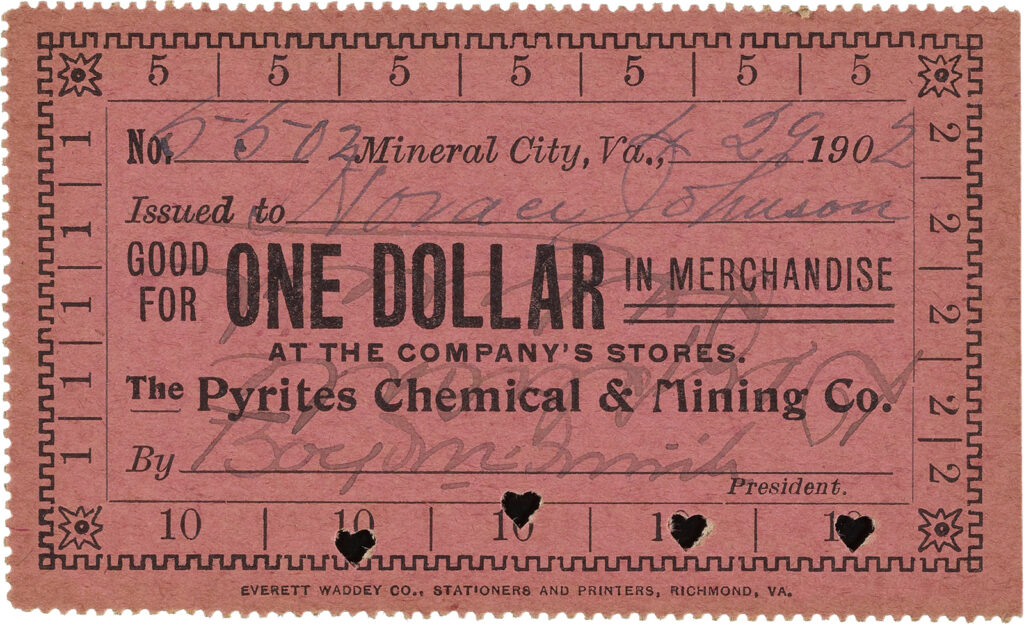

Perhaps the most well-known examples of scrip were those issued by American mining companies beginning in the late 19th century. These operations were often located far from the beaten track, which limited access to cash and supplies. Miners were paid their wages in cash, but if they ran out before their next paycheck, they could use the company’s scrip as a loan to buy goods at the only store nearby, the company store.

But scrip systems could be used to shackle workers to mining companies, which often charged new employees transportation and equipment fees, as well as first and last month’s rent. Compounding the problem, miners were not guaranteed a stable income; when the price of coal dropped, so could workers’ hours. Miners struggled to pay off the debt, subsisting on scrip loans. What’s worse, many companies would not exchange their scrip for an equal amount in dollars. A Supreme Court ruling in 1918 was meant to end this practice, but it persisted through the Great Depression.

This economic bondage was captured in Merle Travis’s “Sixteen Tons,” a song made famous by Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1955.

“My Dad never saw real money. He was constantly in debt to the coal company,” explained Travis, who grew up in the hills of western Kentucky. “When shopping was needed, Dad would go to a window and draw little brass tokens against his account. They could only be spent at the company store. He used to say, ‘I can’t afford to die. I owe my soul to the company store.’ ”