Bert Hansen. Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio: A History of Mass Media Images and Popular Attitudes in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009. 348 pp. $37.95.

On 2 December 1885 a stray dog bit four Newark, New Jersey, boys. The event was hardly uncommon. Fear of feral dogs and the possibility of rabies, an untreatable and horrifying disease, ran high. Local papers reported the incident, which was again not unusual. However, this particular occurrence blossomed into an international news story that captivated the public for months. Two powerful innovations of the late 19th century—mass media and scientific medicine—joined forces to create what Bert Hansen in Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio calls the “first medical breakthrough.”

Hansen traces the history of mass-media images of medicine from the rabies-vaccine story of 1885 to the development of Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine in the mid-1950s. He examines how stories, illustrations, cartoons, and photographs culled from magazines, newspapers, comic books, and movies reveal much about public attitudes to medicine and the popular appeal of medical news during this period. Hansen presents material previously unexplored by medical historians, while maintaining a clear narrative style accessible to the general reader.

Less than two months before the New Jersey incident Louis Pasteur announced the success of his rabies vaccine. The vaccine, produced from weakened infectious material extracted from rabbit spinal cords, prevented the development of rabies only if it was injected in the patient soon after the bite had occurred. The vaccine represented the first practical application of recent developments in germ theory and immunology, resulting in a cure for a human disease.

The boys sailed to France for the novel Pasteur treatment. A public plea for contributions to pay their expenses was made through the local paper. Newspapers in New York and other major cities picked up the story, as did the newly prominent and nationally distributed weekly magazines. Stiff competition for readership guaranteed that publishers would wring everything possible out of a story once the public’s curiosity was aroused. Improved printing techniques created a visually compelling new media, where full- and half-page illustrations and cartoons replaced columns of text. Soon, it seemed, the entire nation was following these boys and their families—from their stay in France and treatment by Pasteur to their trip home as returning “heroes” and subsequent tour of American cities. For the first time a large segment of the population read the same stories and saw the same images. Mass media created a “medical breakthrough.”

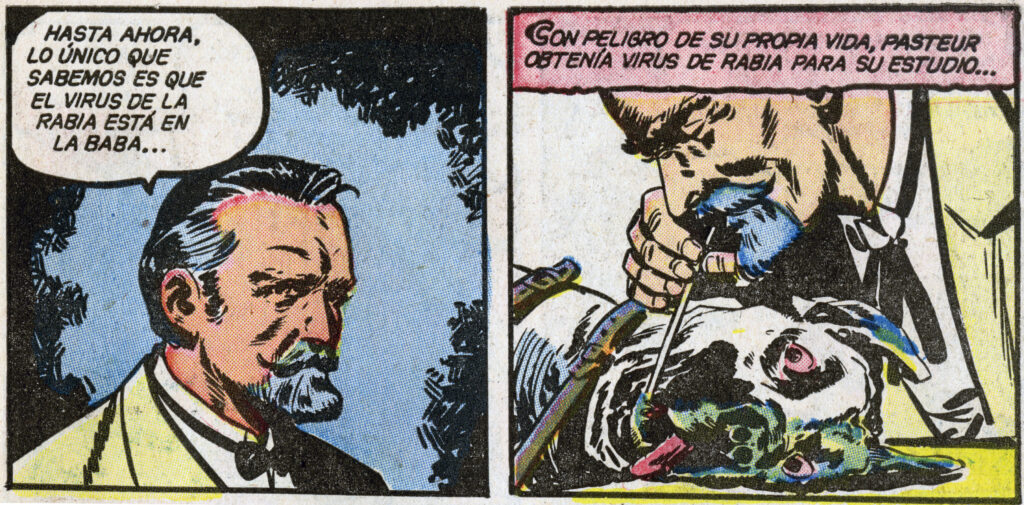

Panels from “Louis Pasteur, Benefactor de la Humanidad.”

The Pasteur story served as a template for further medical-news breakthroughs, including Robert Koch’s announcement in 1890 of his tuberculin therapy (although it soon proved ineffective) and the development of an antitoxin cure for diphtheria in 1894. The coverage of these events established in the public mind a new respect for medicine and for the potential of laboratory science, creating a new type of hero in the form of the medical scientist.

By the 20th century the public’s enthusiasm for news about medical science and progress was firmly established. The new century saw these stories diffuse into books, radio, movies, and comic books. In 1926 the publication of Paul de Kruif’s best-selling book The Microbe Hunters gave the older medical heroes a singular boost. De Kruif’s lively and dramatic retelling of the stories of Pasteur, Koch, Paul Ehrlich, and others not only spawned more popular science writing but also launched a wave of popular medical biographies adapted for radio plays, theater, and movies.

Hansen further describes how in the 1940s a new literary genre had an enormous impact in spreading these stories to a younger generation. True Comics debuted in 1941 and was soon followed by others, including Real Life Comics and Real Heroes. Under the banner “TRUTH is stranger and a thousand times more thrilling than FICTION,” the stories of Walter Reed, Robert Koch, Alexander Fleming, and dozens of others fighting the “war against disease” ran alongside stories of generals and world leaders fighting the war in Europe. The comic-book stories were tightly compressed and used an economy of drawing and text to drive the action forward. The triumph of the hero and his scientific method was assured. These inexpensive and widely distributed books proved immensely popular—especially among children and GIs.

Hansen concludes with a look at LIFE’s coverage of medical stories up to the mid-1950s. Through its creative format and the singular artistry of its photography, LIFE played an important role in teaching and popularizing science. Henry R. Luce, who launched the magazine in 1936, wanted his readers “to see and take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed.” Pleasure, amazement, and instruction aptly describe the LIFE approach to presenting science. The image of medicine projected at mid-century through LIFE’s photo essays was unfailingly optimistic.

A collector himself, Hansen clearly has a love for the graphic image, and many of the 108 illustrations and 22 color plates in the book come from the author’s own collection. The chapters on late-19th-century magazine illustrations, 1940s comic books, and LIFE are the strongest and receive the most in-depth treatment. As befitting a book about graphic representation, the illustrations are beautifully reproduced, many at a full or nearly full page.

Pasteur’s rabies vaccine marks a clear beginning to the era, but the ending is much less distinct. In the mid-1950s the world greeted Jonas Salk as a modern-day medical hero, much in the vein of Pasteur. His polio vaccine marked another triumph of medical science over a dreaded disease. Since then public attitudes have shifted away from wholesale optimism. Our esteem is now tempered by an awareness of the limits of medical science, its unexpected consequences and potential for misuse, and the fallibility of the men, women, and institutions that pursue it. This study of the mass media’s role in disseminating medical information and shaping public attitudes is both highly relevant and enjoyable. It invites reflection on the importance of balancing optimism and skepticism and the value of “heroes” in promoting belief in the power of individual achievement.