Werner Troesken. The Great Lead Water Pipe Disaster. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006. x + 318 pp. $29.95.

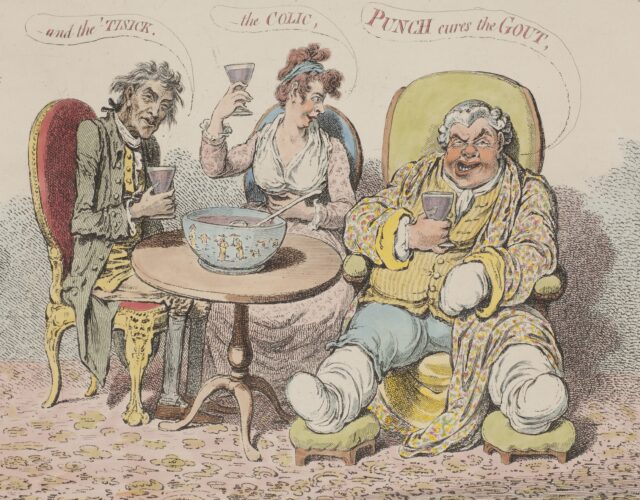

Throughout the history of environmental poisoning by humans, lead has been acknowledged as a major culprit. Its toxic effects were recognized as early as the 2nd century BCE, and more than one scholar has argued that chronic lead poisoning was a significant factor in the fall of the Roman Empire. The ancient Romans were most certainly exposed to lead, as the material was employed for plumbing, cookware glazes, paints, and cosmetics. These, along with other applications, continued through the medieval era. Lead found its way into alcoholic beverages through several routes. In the 18th century it caused Devonshire colic, which plagued the cider drinkers of southwestern England. It also caused gout among British aristocrats, who consumed port wines containing lead acetate: lead depresses kidney function, inhibiting the excretion of the uric acid that causes gout. Even bonbons and sweetmeats were sometimes contaminated with such brightly colored lead compounds as yellow chromate, which was used in an eye-pleasing glaze.

In the early 19th century, industrialization promoted a closer study of the health problems of workers in mines, factories, and other settings. In these first stages of development of occupational medicine, lead dominated discussions of poisoning in the workplace. Miners, smelters, painters, enamelers, glazers, typesetters, and other types of workers were identified as victims of colic, emaciation, anemia, wristdrop, and encephalopathy from exposure to lead. The list of those at risk expanded as industrial chemistry advanced. By the early 20th century the population of the Western world at large was exposed to lead in paints, pesticides, and the gasoline additive tetraethyl lead.

The growth in recent decades of the specialty of environmental history has generated several books that explore the dangers of lead poisoning, also known as plumbism, in the past; but until now, one of the most common sources of lead poisoning in modern times—water supplied to houses through lead pipes—had been largely neglected. Troesken’s volume remedies that neglect.

The disaster of the title began in the mid-1800s in North America and the British Isles with large-scale installation in urban areas of piped-water systems, which replaced collection by hand from rivers and wells. From the beginning lead was the most appealing material for water pipes, which carried water from street mains into the household: it was affordable and was more durable than wood, iron, and tin, the other materials available at the time. Despite the long history of awareness of lead’s toxicity, chemists and physicians supposed that water flowing through the pipes would not dissolve enough lead to present health problems to consumers. The supposition was wrong, of course. Depending on a variety of factors, most notably the hardness or softness of the water, lead could dissolve in concentrations that were dangerous, even deadly. An alarming statistic in the book shows 19th- and early 20th-century concentrations of lead in U.S. and British drinking water were equal to hundreds and sometimes thousands of times the level recognized today as the maximum safe concentration by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Troesken carefully examines the medical community’s uncertainty during this period with respect to the threat of lead in water. Some physicians feared that consumers were being poisoned, but the majority were either skeptical or certain there was no danger. In most cases, after all, the poisoning produced was not acute but chronic, developing slowly and in the early stages easily mistaken for other complaints. Furthermore, physicians were focused on the health of adults, but children and fetuses were most at risk. Drinking water in many cities in Britain and the United States supplied dosages of lead capable of inducing abortion. This threat was recognized by some physicians by the early 1900s and was taken up by adherents of the eugenics movement as a hazard that threatened to bring about “race suicide.” There is also a compelling argument made that lead in water significantly increased the incidence of eclampsia in pregnancy.

As scientists and engineers came to better understand the nature of plumbism in the early 20th century, they took a range of government-mandated steps to lower the risk of poisoning from water pipes, including chemically treating water to inhibit lead solubility and replacing lead pipes with conduits made of safer materials. The gradual introduction of polyvinyl chloride (commonly known as PVC) pipes in the second half of the twentieth century finally got the lead out of most drinking water, though as Troesken notes in his concluding chapter, lead levels still exceed EPA standards in some districts in the United States.

Troesken’s book is based on extensive research in the chemical and medical literature, government publications, court cases, and newspaper stories, as well as statistical analysis not often encountered in historical studies. The narrative nicely blends chemistry with the political and economic forces that shaped decisions about water supply and is rich in illustrative anecdotes. The book would benefit from tighter organization, and more could be said on recent developments that have brought the problem under control. Nevertheless, The Great Lead Water Pipe Disaster is a valuable addition to our understanding of the chemical health hazards associated with modernization in Western society.