The guests assembled in the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C., know the gravity of their mission. It’s not every day the president of the United States summons a conference. But Franklin D. Roosevelt has, and close to a thousand experts have answered his call. They mill under the gold-trimmed torchères in the hotel’s block-long indoor promenade. It’s a drizzly and warm May 26, 1941, but the Mayflower has installed some of the new air-conditioning machines, making the temperature inside pleasant. Outside, the city is in bloom, the trees lush.

The world situation, though, is grim. Hitler has attacked the island of Crete, after having successfully conquered mainland Greece the month before. He now controls more of Europe than ever. Tensions with Japan are flaring. It’s beginning to look inevitable that the United States will be pulled into the war. Already, the military is building thousands of new bomber planes, tanks, and battleships. But there’s another aspect crucial to war, and that’s what the experts at this symposium—the National Nutrition Conference for Defense—have come to discuss: food.

Food can make or break a military campaign. Roman armies were successful in building an empire partly because Rome excelled at constructing roads and establishing shipping routes, which helped distribute grain, olive oil, and other supplies to its soldiers. And while strong supply lines kept the Northern armies well provisioned during the Civil War, many Confederates went hungry once blockades and a deteriorating railroad system cut off their replenishments.

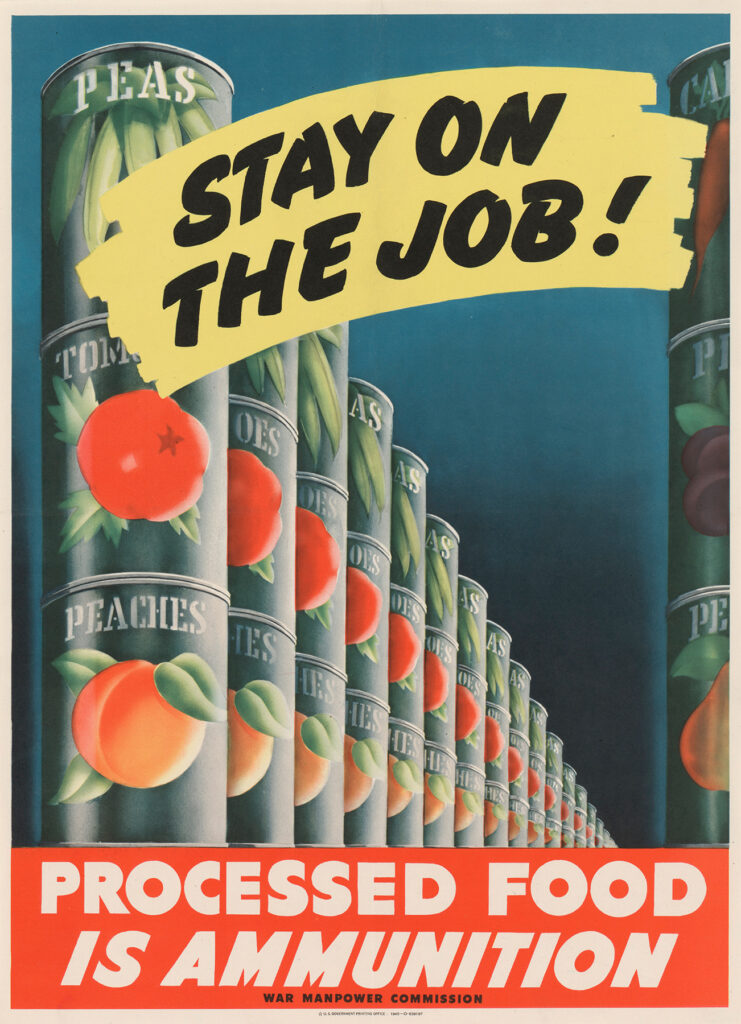

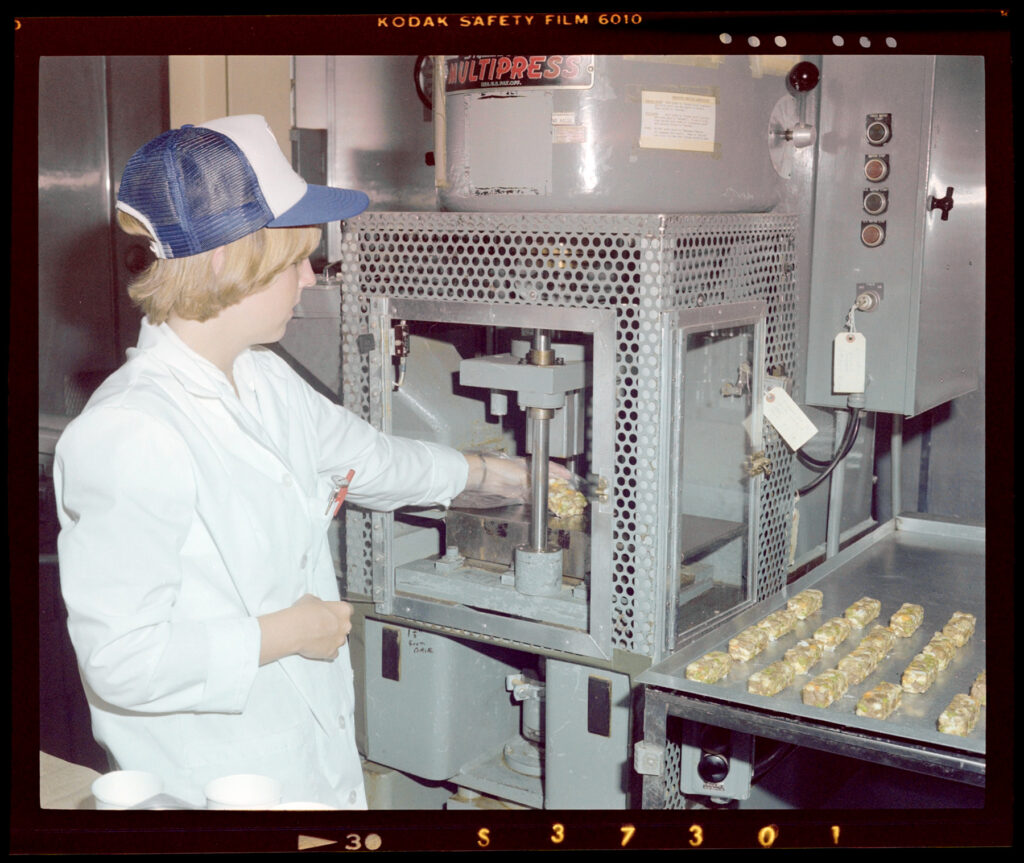

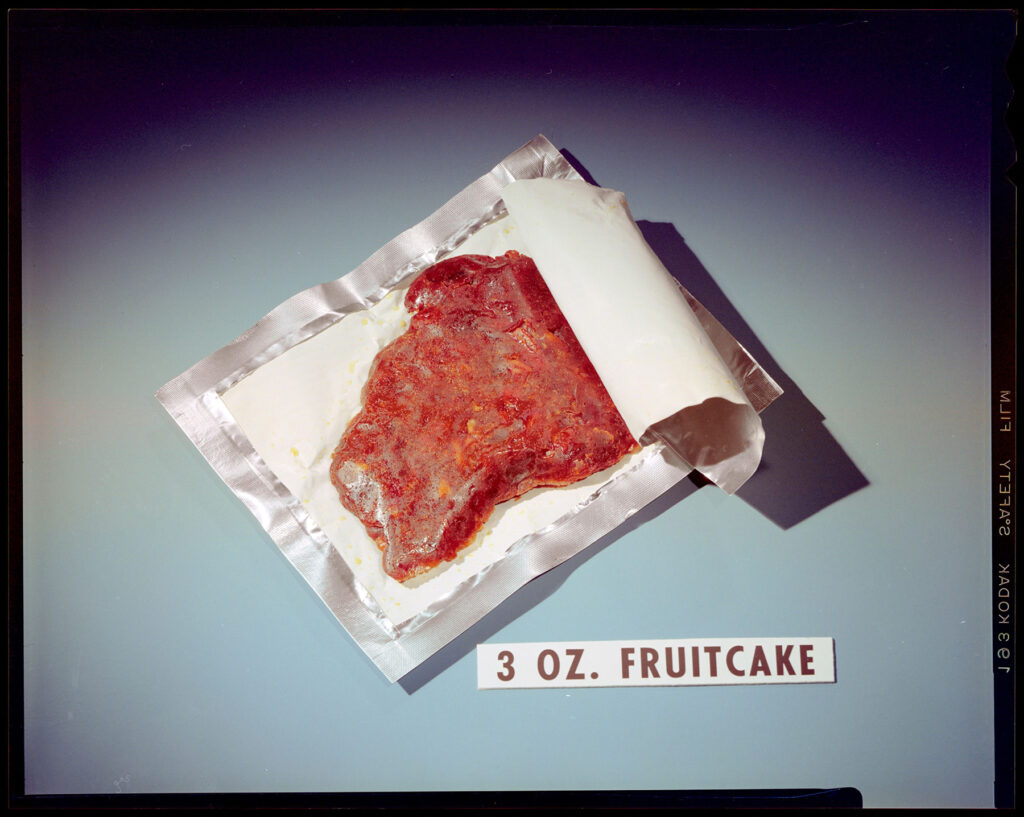

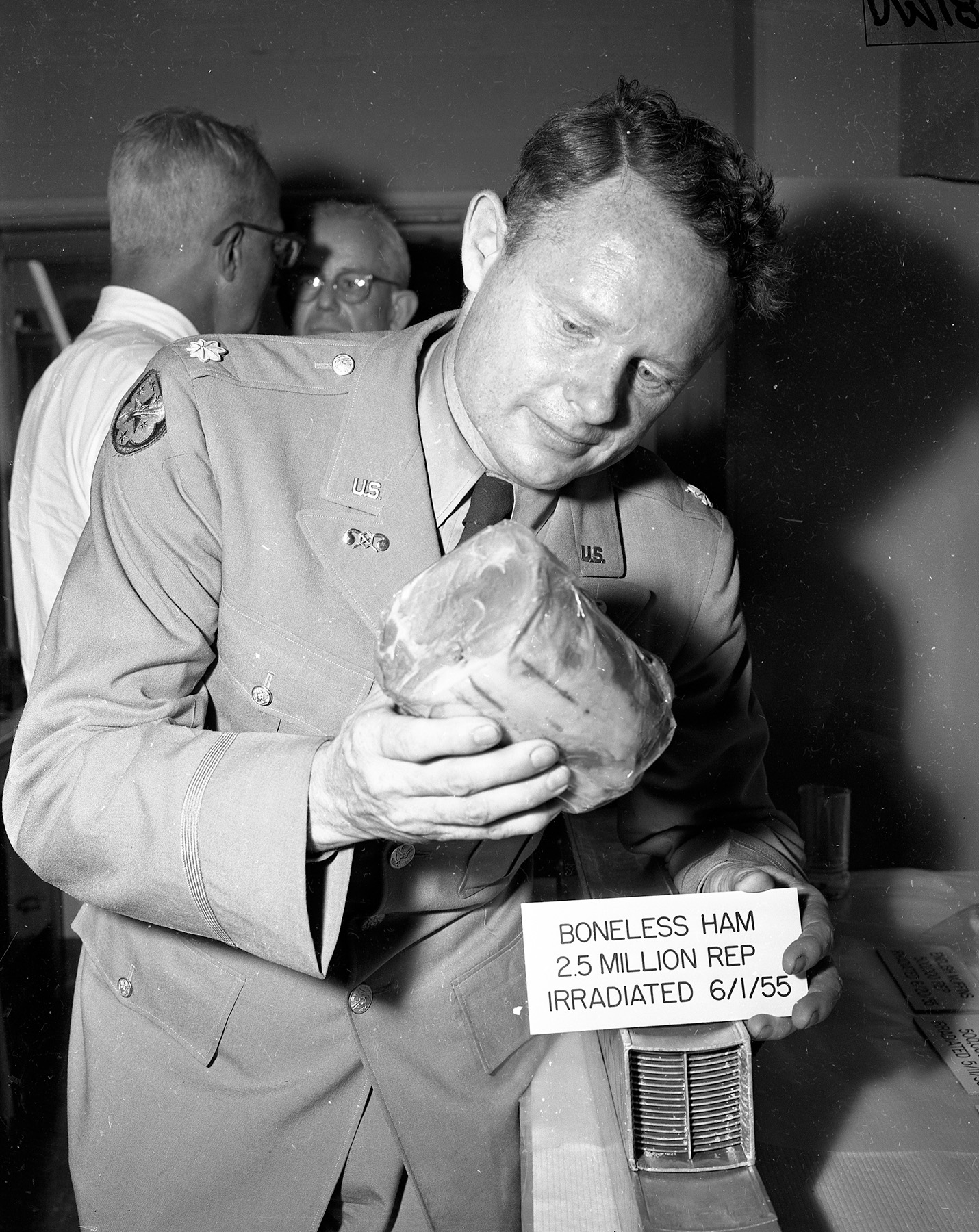

For the United States, entering World War II will mean growing, processing, and shipping enough food to feed millions of uniformed personnel. And there’s a related challenge, the one that has brought some of the country’s leading doctors, dietitians, farmers, and food manufacturers to this conference: who will fill the ranks of this gigantic army?

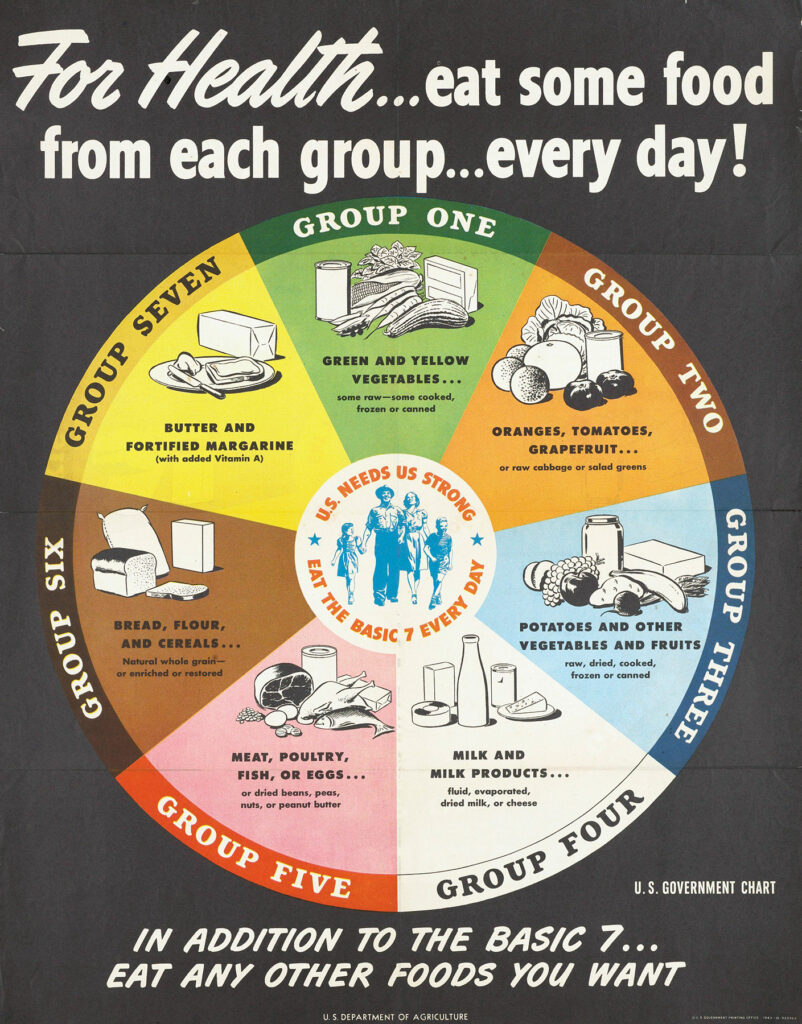

Eight months earlier, Congress passed a law requiring American men to register for the draft. So far, a million citizens have done so. But two out of every five have been rejected, often because they are badly nourished. This threatens both the country’s prospects on the battlefield and its ability to staff essential war industries at home. Something must be done. Federal Security Agency administrator Paul McNutt opens the conference with a letter from President Roosevelt, whose words underscore the urgency: “During these days of stress the health problems of the military and civilian population are inseparable. Total defense demands manpower.”

Few of those assembled could predict the extent of it, but in the years and decades that follow, the country will take numerous steps to ensure it has a well-fed defense, be it at home or abroad. These actions will—sometimes intentionally, other times less so—profoundly change how the entire nation eats.

Today, entire supermarket shelves are dedicated to products that were directly or indirectly molded by a military-inspired vision of food. An estimated half, and counting, of the items in a typical grocery store can trace their origin or success to the military’s influence. And how we even think about food and nutrition today is significantly framed by national defense considerations dating back to World War II. As scholars Tanfer Tunc and Annessa Babic concluded in 2017, “The degree to which the U.S. military shapes the American diet cannot be underestimated.”