“Don’t step on my babies,” Buzz Ferver orders, more than once. His loafers have all but disappeared into a dense carpet of dandelions, making it difficult to walk in his footsteps, as instructed.

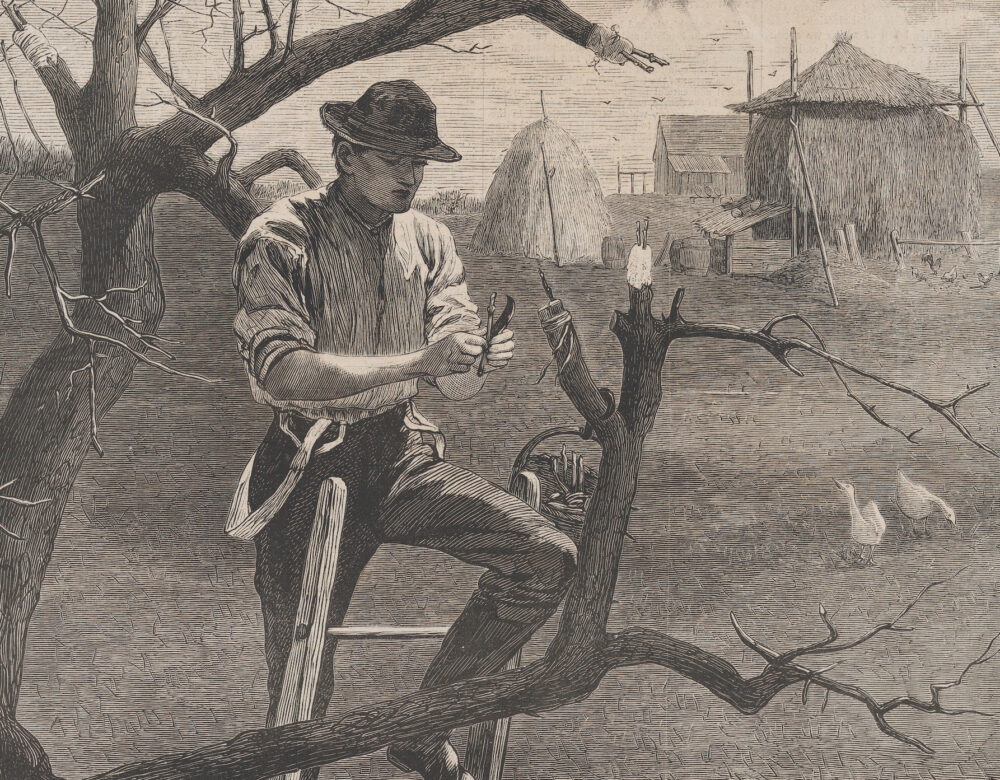

On his Perfect Circle Farm in the shadow of Vermont’s craggy Worcester Range, Ferver picks his way through rows of small trees. He inspects grafts—the places where he’s sliced open the bark of a rooted sapling and fused it with a cutting from the tree he wants to clone—and straightens the long sticks he ties to each young trunk to keep birds from perching on the delicate new growth. Raised in the Delaware Valley outside Philadelphia, Ferver relocated to Vermont in 2004 and bought this farm in 2015. In the intervening years, he estimates he’s “killed untold thousands” of seedlings while attempting to produce hardy trees in the New England climate. To the untrained eye, Perfect Circle is a typical, if especially idyllic, tree and plant nursery. But as he carefully prunes a yearling hican tree, Ferver announces his greater mission: “I am building an ark.”

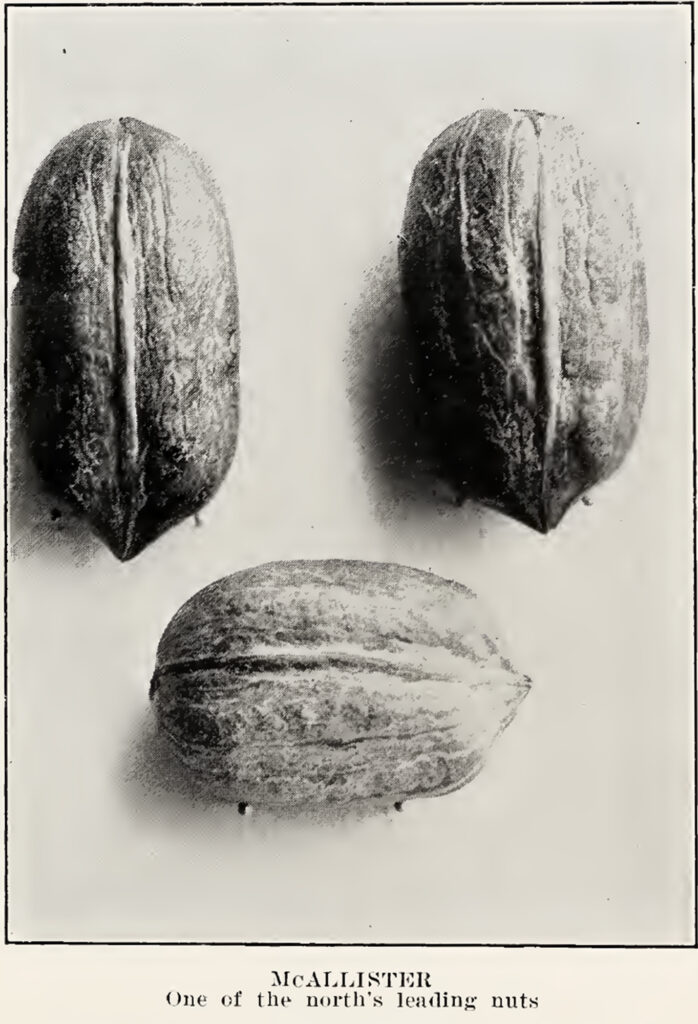

The hican is a remarkable, unlikely thing. It’s a hybrid of pecan and hickory, both members of the Carya genus and close enough relatives that occasionally, when the conditions are just right, cross-pollination can occur. What results is a towering, rough-barked tree, thick with foliage, that produces a sweet, palm-sized nut.

In Ferver’s field, spindly hican seedlings bear labels with their ancestral name: “McAllister—Hershey.” They’re descendants of a massive hican, 100 feet tall and nearly as wide, planted a century ago by a legendary Pennsylvania nurseryman named John W. Hershey. That tree is dead now, cut down in 2019 to make way for an apartment complex. But Ferver has devoted his life to preserving Hershey’s McAllister hican and a huge variety of other nut and fruit tree species. He’s part of a group of hopeful dendrophiles who believe the farms of the future will forgo neat rows of crops baking under the hot sun.

Instead, they’ve embraced food forests: wooded plots that feed livestock and people alike, all of it anchored by nut trees. Ferver and his ilk are determined to preserve the genetics and provenance of the best pecans, chestnuts, hickories, hazelnuts, walnuts, butternuts, heartnuts, oaks, honey locusts, persimmons, paw paws, plums, pears, mulberries, and more—the cultivars that will feed the future. That’s the “ark” he’s talking about. “I’m trying to leave behind a germplasm that, from a climate perspective, from an ecological perspective, and from a human survival perspective, we’re going to need,” he says.

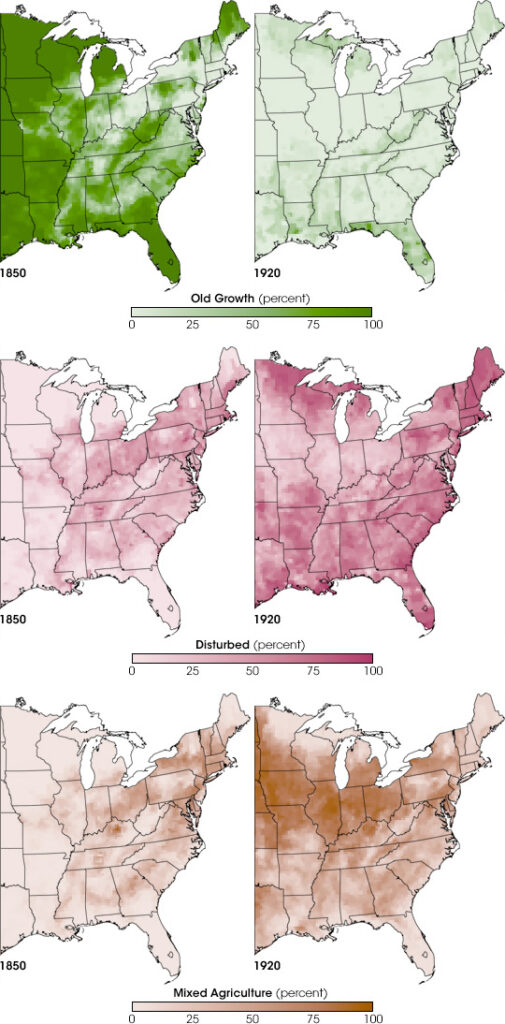

Agriculture, as we imagine it, is a relatively recent invention in North America. While the earliest European colonists farmed at a subsistence scale, a mid-18th-century population boom in Europe created a thriving international cereals market, and American farmers responded by clearing huge acreages of hardwood forest to plant wheat and corn. The introduction of the cotton gin and a growing global textile trade fueled the expansion of Southern plantations.

Throughout the 19th century, pioneers poured over the Appalachian Mountains to claim tracts of land issued by the federal government or purchased from the rapidly expanding railroad. Immigrant European farmers descended on the American prairie and planted ever more wheat fields, while the Great Plains, now devoid of the massive, migrating bison herds of yore, became pastureland for countless cattle operations. Mechanization of farming equipment after World War I allowed for even more expansion, and our industrialized food production system was born.

But that system is unsustainable. The United Nations calls industrial farming “fundamentally at odds with environmental health.” In 2020, according to EPA estimates, the nation’s agricultural operations emitted more than 11% of the nation’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

Chemical fertilizers, pesticides, antibiotics, and growth hormones used to increase yields are also a proven risk to human health. And just as agriculture contributes to climate change, the changing climate has a direct impact on farming. It’s clear, says Ferver, that agriculture will face a reckoning.

“At some point, we may want to replace 200 million acres of corn with something that has high food value, sequesters carbon, and will live for 100 years,” he says. Nut trees could be part of the solution.

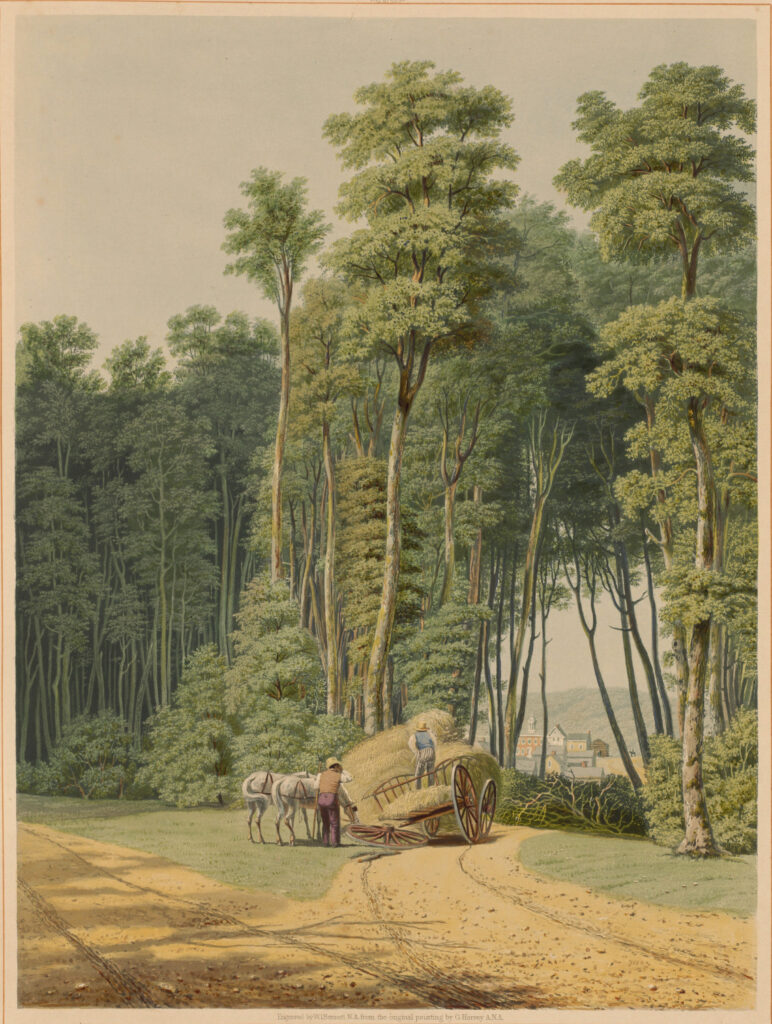

Before colonial settlement, the Atlantic Coast was one of Earth’s richest biomes: a great, dense forest of hardwood trees that spread from Maine to the Gulf Coast, and west past the Mississippi River. Indigenous people farmed that forest, selecting for the best-producing trees with the sweetest nuts and highest disease and pest resistance. Their efforts culminated in a dependable crop of food high in oils, carbohydrates, and protein that fed people, livestock, and wild game.

So, agroforestry—a system that integrates pasture, ground crops, and shrubs beneath a tree canopy—isn’t a new concept, though the term was coined as recently as the 1970s. Decades earlier, in 1929, University of Pennsylvania geographer J. Russell Smith published Tree Crops: A Permanent Agriculture, in which he advocated for a return to that kind of sustainable, ecosystem-supporting tree crop production. Today he’s commonly referred to as the father of agroforestry, and he instilled its tenets in his young protégé, John W. Hershey. Hershey was in his early 20s in 1921 when he opened a small nursery in Downingtown, Pennsylvania, less than an hour’s drive from Philadelphia. He sold his trees locally and published catalogs and pamphlets that encouraged soil maintenance and regenerative farming practices with roots in Indigenous techniques.

Before colonial settlement, the Atlantic Coast was one of Earth’s richest biomes: a great, dense forest of hardwood trees that spread from Maine to the Gulf Coast, and west past the Mississippi River.

In the early 1930s, as part of the New Deal, President Franklin Roosevelt created the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to help revive a region hit hard by the Great Depression. As part of the initiative’s environmental and agricultural goals—including preventing a Southern version of the Dust Bowl that was pummeling the American prairie—a tree crops division was established. When the division’s chairman asked Smith to suggest a man to lead the operation on the ground, he called on Hershey. Though Hershey had no formal forestry degree, the young Quaker saw the job as a spiritual and patriotic calling. “It is more important to save this country by growing trees and preserving the soil, than it is to try to save it by sending men to war,” he would later write in a self-published book.

Hershey ran TVA-sponsored contests, advertising in local newspapers and encouraging farmers in the valley to send in material from their best trees for cash prizes. “Hershey’s tree-crops section in the TVA offered prizes for the best acorns, the best honey-locust pods, the best persimmons, the best blueberries, and other wild fruits,” wrote Smith in a 1953 edition of Tree Crops. The winners came from old trees on Southern farms, many of them almost certainly the work of Indigenous forest farmers.

Hershey’s TVA nursery flourished, and the best seedlings and grafted young trees were grown and propagated, their progeny distributed to farms across the valley. In 1939, Hershey returned to Downingtown and brought the genetics of those carefully bred cultivars with him. By 1945, he had expanded to 75 acres. It was a treasure trove, “America’s No. 1 Tree Crop Farm,” according to Smith.

Hershey believed it would be the wellspring for a wider reforesting movement. A farmer far ahead of his time, he evangelized about organic gardening practices and soil health, water retention, cover crops, and rotational grazing. He foresaw a return to a kind of agriculture that would feed people, livestock, and game alike and produce timber and other income sources for farmers. On his plot in Downingtown, the vision came to life.

Hershey’s livestock grazed beneath the trees. Fat honey locust pods fed horses and cows, and when the chestnuts dropped their spiky burrs, the steers ate the sweet nuts inside. Persimmon and mulberry trees stained the ground with their fruit, a veritable feast for Hershey’s pigs. In autumn, the farm was a palette of red, orange, and yellow, and each spring, thick new growth wove a lush green roof over this burgeoning paradise.

The experiment was repeated by other legendary nurserymen who followed Hershey. Speak to anyone in the informal northeastern nut tree network, and you’ll hear the same names repeated again and again: Archie “Mr. Black Walnut” Sparks; John Gordon, an eccentric grower of uncommon cultivars; American chestnut devotee Arthur Graves.

After a career as an oilman, James Claypool retired to his Illinois hometown and spent the next 25 years as the world’s foremost breeder of persimmons. Fayette Etter was a telephone lineman who hunted for the best wild hickories along his service route to use in grafting and crossbreeding experiments. Sometime in the 1950s or 1960s, Etter ended up in a courtroom in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, arguing against a planned bridge-improvement project that would require cutting down a shagbark hickory tree he had dubbed the “Keystone.” As the story goes, Etter gave the judge a hickory nut to crack. Declaring it “the finest nut I’ve ever seen,” the judge ordered the bridge relocated further downstream. A flood the following year took out both the new bridge and the tree, but not before it had been grafted and cloned. On his farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Parker Coble, a local teacher sometimes affectionately called “the Nutty Professor,” grew English walnuts the size of a tennis ball and established one of the nation’s biggest plantings of butternut trees.

But of all the many celebrated names and reputations in the world of nut growers, none looms quite so large as Hershey’s, even though he spent much of his career working in a diminished health capacity after a cancer diagnosis in 1936.

In the 1960s, with the illness advancing, Hershey began laying plans for the future. He proposed that the Brandywine Valley Association, the nation’s first small watershed alliance, acquire the property and preserve it as an arboretum. In the end, the association decided to use the funds for other projects. Hershey died in 1967. “The tree crop farm had to be sold. The nursery closed down. Dreams sometimes end like this,” his wife, Elizabeth, wrote. The land was parceled out and developed. Today, Downingtown is a busy suburb of shopping centers, retirement homes, and townhouses. But many of the trees are still there, if you know where to look.

Although rarely marketed as such, a nut is technically a dry, single-seeded fruit. Some, like acorns, chestnuts, and hazelnuts, are considered “true nuts”: they contain both a tree’s amalgamated fruit and seed, and they’re indehiscent, meaning the hard, inedible shell or hull doesn’t split open when ripe. Others, like almonds and cashews, have a fleshy outer fruit around a seed, which is the part we eat. These fall into a category called drupes, though the USDA nonetheless classifies them as nuts.

Across species, nuts are chemically constructed of proteins and lipids and are rich in health-supporting compounds, including unsaturated fats; fiber; vitamins; phytosterols, which can help lower cholesterol; and phenolic compounds, which work as antioxidants. In studies, nut consumption has been shown to lower blood pressure and is associated with a decreased risk of coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and cancers.

Nuts are well-suited to long-term storage and lend themselves handily to an array of preparations: raw, roasted, or ground into flour. Even a small acreage of nut trees can be a significant food source. A single healthy walnut tree can produce more than 300 pounds of nuts in a good season. The mast of a one-acre orchard of mature pecans can weigh as much as a ton. Many nut tree species alternate years of big production, but they’re reliable; they can produce for 50 years, or, in many cases, much longer.

Calorically, that’s a huge amount of food. According to the USDA, walnuts provide 730 kcals per 100 grams (or roughly 3.5 ounces), double the energy in the same amount of corn and considerably more than both soy and wheat. The comparison is similar between traditional crops and pecans, hazelnuts, and many other nut varieties.

Because nut trees cross-pollinate, there are endless genetic combinations within each variety (and sometimes, as in the case of the hican, across varieties). That also means seedlings can vary widely from the parent plant and makes it difficult to grow dependable producers from seed. The solution is to simply clone the parent tree by grafting. In Downingtown, the hidden-in-plain-sight remnants of Hershey’s farm are a master class in successful grafts and superior cultivars.

“There’s a triple-grafted walnut outside this preschool, and a whole grove of hickories and chestnuts and persimmons inside this apartment complex,” says Max Paschall. An arborist and gardener at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Paschall possesses an exuberance that makes his passion for Hershey’s trees obvious. “You’re looking at a persimmon, then you realize, ‘that’s a honey locust and, oh, that’s a white oak.’ You realize you’re surrounded by food-producing trees,” says Paschall. In a Philadelphia suburb, he contends, this is as close as you can get to “waking up in the Garden of Eden.”

Though Hershey’s name has been well known among nut growers, the existence of his surviving trees went largely unnoticed for decades. It’s thanks to Paschall that they were, in effect, rediscovered. In 2015 he read an article about Hershey in “some obscure permaculture publication.” He drove to Downingtown and was stunned by what he saw. Later that year, at a meeting of the Backyard Fruit Growers, a local enthusiasts’ group, Paschall told fellow tree aficionados about what he found. Soon, a loose group of Hershey preservationists had formed and began taking regular trips to Downingtown to collect nuts and scion wood—the cuttings used to clone a tree by grafting. In the years since, the group has fought to save a number of Hershey’s most iconic trees as suburban development grew. Some battles were won. Most, such as the struggle to save the massive McAllister hican, were not.

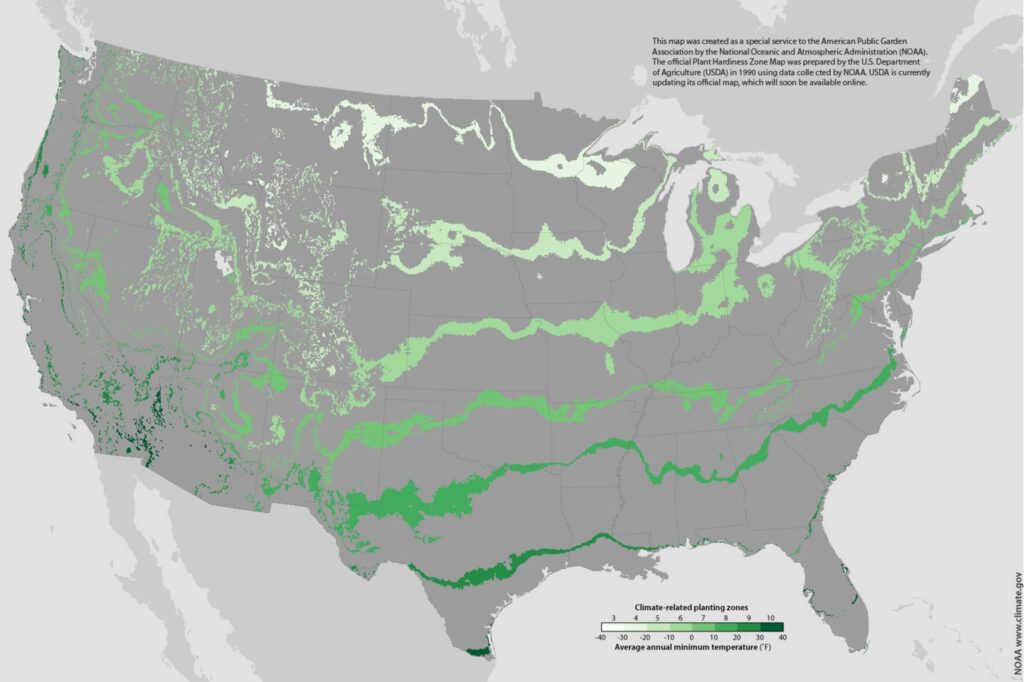

It’s not just their history that makes the trees special. For the most part, they’re the clones and direct descendants of trees that thrived in the south, in the kind of climatic conditions anticipated to spread across northern states in coming decades. The USDA maintains a “hardiness map,” which divides the United States into growing zones based on annual minimum temperature. The map is a guide to help growers know when to plant and what is likely to thrive in each zone. In the map’s 2012 update, all the lines shifted north, moving much of the country warmer by half a zone from 1990, when the map was previously updated. In 2018, researchers at the University of Idaho examined how hardiness zones would shift as a result of climate change. They predicted the map’s lines will move north at a “climate velocity” of 21.4 km per decade.

The progenitors of Hershey’s trees were thriving in southern hardiness zones when he collected their genetic material. The resulting plantings have withstood Pennsylvania frosts for the better part of a century and survived that long with largely no maintenance—no one to spray, prune, or fertilize. And yet they go on producing, year after year. In other words: they may be the closest we can get to a “future-proof” crop.

“If we’re looking for trees that can survive massive heat waves, or a climate where a third of the year is over 100 degrees, or there’s drought, or there’s frost . . . these trees have proven their mettle,” says Paschall. “When I hear people worrying about our future ability to feed ourselves . . . we don’t need a biotech solution or some new machine. We have a collection of trees in a suburb of Philadelphia.”

Converting industrial farms to forests won’t happen overnight. It won’t happen in any kind of hurry at all: major cultural and commercial forces are resistant to such a major shift in farming practices, and even if landowners do jump right on board, most nut trees take several decades to begin producing. But silvopasture, an agroforestry practice that involves strategically planting trees to improve existing grazing pasture, may provide a bridge.

There are more than 650 million acres of cow pasture in the United States—the largest single use of land in the country. For Austin Unruh, it’s land of opportunity. He heads up Trees for Graziers, an organization that works directly with landowners to strategically plant trees in their pastures. Choose the right trees, Unruh says, and the merits multiply. He often plants honey locusts and persimmons, which provide shade and a source of fodder that drops in the colder months, keeping feed bills low while adding energy to livestock diets.

In the last two years, Trees for Graziers has created around 400 acres of silvopasture on 30 farms, planting a total of nearly 25,000 trees. The honey locusts they use, which produce foot-long pods loaded with sweet goo, are a tree selectively bred by Hershey. The persimmons, too, are Hershey varieties, borne from trees in Downingtown. Each one that ends up in a pasture makes an impact, says Unruh, on people and the planet.

Silvopasture and other agroforestry practices do more than provide shade and an alternate fodder source. Adding trees can make all the food more nutritious. They create habitat for animals, including pollinators, small herbivores, and predators of both. Animal biodiversity contributes to plant biodiversity, and cycles begin to form. The soil gets healthier and so does everything that grows in it, says Robbie Coville, ecosystem products and markets specialist with the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources’ Bureau of Forestry. More informally, Coville is the state’s new agroforester: his job is to create and expand markets for forest products, including nuts, and improve forest management on public and private land.

“Big things start to happen with any kind of shift toward the perennial,” says Coville. “Soil health is going to improve a lot based on the soil food web improving.” The undisturbed ground around trees has an increased number of microorganisms, he explains, which provides for a bigger community of insects and ultimately makes the soil more nutrient-dense. Water also behaves differently on silvopasture, where deeper root systems prevent erosion and increase infiltration, ensuring that rainwater moves through the soil rather than running off into gullies and ditches and carrying away topsoil with it.

“Storing carbon is the big piece,” says Coville. Project Drawdown, a climate-solutions nonprofit, estimates that pastures with more than 30% tree cover can capture and store as much as 10 times more carbon than treeless expanses of grass the same size. Based on data from eight different studies, the group claims each acre of silvopasture can sequester six metric tons of atmospheric carbon per year, nearly the equivalent of five cars’ annual emissions.

While the long-term benefits of agroforestry are an easy sell to farmers, the initial investment is not, says Unruh. Growing trees isn’t a quick business, and many landowners are still wary. Trees for Graziers is working to allay those concerns. The group helps farmers secure funding to subsidize silvopasture plantings.

“We’re seeing a much bigger federal investment in regenerative agriculture and climate-smart forestry,” says Coville. “That definitely extends to agroforestry. What I think we’re also seeing play out here in Pennsylvania is more investment from philanthropic foundations and from private-sector investors.”

Ultimately, agroforestry’s advocates believe it will emerge as the most reasonable solution to agriculture’s mounting challenges. As the population grows and farm acreage is converted to urban landscape and development, there’s a need to grow more food on less land.

A few hundred new acres of silvopasture may be a drop in a very large bucket, but every farmer willing to plant trees on even a single acre is taking a step in the right direction, says Ferver. And that’s how momentum builds. “You don’t need everybody,” he says. “You don’t need a majority. You need between five and ten percent of the people to say, ‘We’ve got to do this.’ ”

Forests play a crucial role as carbon sinks, but reforestation alone isn’t enough to reverse climate change and faces skepticism on numerous fronts. Trees take years to grow and sequester carbon, but sequestered carbon is released into the atmosphere in the event of a wildfire. Even where reforestation is successful, the trees themselves can worsen wildfire potential and water-use issues in drought-prone areas.

Nut tree farming is likely to face many of the same challenges, but, done correctly, it could offer more solutions than problems. Mature trees are drought-tolerant, and older deciduous trees, such as well-established nut producers, are far less likely to burn than the faster-growing coniferous species often planted densely for the sole purpose of carbon sequestration. Much of the work involved in breeding hardy, disease-resistant tree varieties has already been done, assuming those cultivars can be preserved.

Forests play a crucial role as carbon sinks, but reforestation alone isn’t enough to reverse climate change and faces skepticism on numerous fronts.

“Estate planning and farm succession is a big challenge,” says Coville. In many cases, when older farmers retire or die, their children are unable or unwilling to keep the farm going. It’s an issue that promises to accelerate in the coming decades. Climate change can be difficult to grasp because it requires thinking on a geologic timescale. The benefits of nut tree farming, which require thinking on a generational timescale, can be similarly difficult to make clear to a layperson—never mind local real estate and business interests. In Downingtown, the remains of Hershey’s farm are a cautionary tale. “He had the intention of putting a succession plan in place so his farm would be transferred into something like a trust, but he wasn’t able to do the necessary estate planning in time,” says Coville. “Now we can walk around his past nursery and see the outcome: a lot of subdivision and development.”

The pioneers of nut tree farming are all gone now, and the legendary growers who are still left are in their 80s and 90s. “They are not going to last forever, and what they have is really valuable,” says Louise Bugbee, a biologist in eastern Pennsylvania’s Northampton County who runs a private environmental consulting firm. “But unless someone is able to . . . take care of those trees, then they’re going to be gone just like Hershey’s. What we’ve seen is that when the trees outlive their growers, a lot of times the family sells the farm, they sell the orchard, the land gets divided up, the kids need the money, and the trees are lost to us.”

When Bugbee learned about Hershey’s former farm and the precariousness of the remaining trees, she became determined to give them a new home.

“I just thought, my God, we have to save what’s left. We need a place where these trees can grow and be documented so that we know where they are. A place where, in the future, we can be sure that people will be able to come and collect those nuts and get that scion wood to continue propagating these trees. A place with enough room so that the trees can cross-pollinate at will and hybridize, do their own thing and maybe make that next best nut.”

In a 100-acre public park just off the Lehigh Valley Thruway, Bugbee’s building her own ark. Nearly five dozen tiny trees, grafted by Ferver and wrapped in mesh cages to keep them safe from being trampled or eaten by deer, dot a gently sloping hillside. She plans to add more—a lot more—including cultivars “that are being developed now by growers like Buzz and others like him.” Even if some of the old-timers’ farms do slip away, Bugbee plans to keep the trees (or, at least, clones of the trees) going strong.

“It’s a public space that I knew we could maintain for 100 years,” she says. “A place that would have public access; where we have institutional memory and where we know someone’s always going to be there to care for them; where we have a secure building to keep the records of what we have, where it came from, and why it’s important.”

Nut trees and nurserymen don’t live forever. But good grafts take, and there’s always time to try something new. That, Bugbee says, is the wisdom of an old nut grower. “The beauty of these guys is they’re like 90 years old, and they’re grafting trees and they can’t wait to see what they’re going to get,” she says. It’s a poignant lesson in planting a tree you’ll never enjoy the shade of. In Northampton County, Bugbee says that’s exactly what she’s doing.

“When I give tours, I have to explain what this is not for,” she says. “It’s not for me, it’s not for you. It’s not for us. This is for people in the future. I take them out and I make them stand there. You have to have an imagination for this. You have to imagine that tree in 10 years, in 50 years, in 80 years. You have to imagine that big expanse of field with 10 gigantic trees in it, and they’re all dropping nuts.”