American fashion in the 1920s was often daring, deco, and decadent. Flappers danced the night away in speakeasies, while dapper college boys sported straw boaters and bold two-toned shoes. Silhouettes slimmed, and hemlines rose. But the most essential fashion staple? Why, it had to be the tie-dyed shirt! That’s right: the tie-dyed shirt, in a rainbow of psychedelic shades, was the hallmark look of the Jazz Age.

Well, okay, that last part is simply not true. Tie-dyed clothes—icons of the groovy 1960s and 1970s—didn’t dominate early-20th-century fashion. It’s hard to picture the characters in The Great Gatsby sipping champagne while dressed like the crowds at Woodstock. But in fact tie-dyeing was invented and popularized much earlier than we might imagine, and its emergence in the United States was intertwined with the arrival of new, cheap, and widely available synthetic dyes.

Tie-dyeing—or “tied dyeing,” as it was more commonly known before the 1960s—is an ancient art practiced across continents and cultures. The essential elements are fabric, string, and colorful dye. Among the oldest techniques is bandhani, practiced for more than 4,000 years in South Asia. Bandhani textiles are produced by plucking fabric into tight, tiny knots before dipping it into dye vats, a method that produces exceptionally delicate and complicated patterns. Other, widely varied techniques of tie-dyeing were developed in Southeast Asia, South America, West Africa, and elsewhere.

Historically, tie-dyers used natural colors sourced from organic material, such as the leaves of the indigo plant or the roots of the rose madder. Some natural dyes were more durable than others, but the dyeing process itself was complicated and could involve multiple steps to “fix” the dye—that is, to make it permanent and resistant to fading (also known as lightfast). Fixing natural dyes required mordants, chemical binders that helped adhere the dyes to fiber or fabric. Mordants could be made from alum (potassium aluminum sulfate), salts of iron, copper, or tin, or certain tannic acids, such as those found in oak gall, tea, or sumac bark. With the invention of the first synthetic fabric dye in 1856—an aniline, or “coal tar,” dye extracted from petrochemicals—professional dyers gained both a wide new range of colors and a more streamlined process. Aniline dyes were strong, vivid, more lightfast, and required fewer chemical interventions to “stick” to fabric. A century of use would, unfortunately, prove them toxic, but their brilliant colors changed the direction of fashion forever.

While it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly how tie-dyeing entered American consciousness, one early marker is an article by chemistry professor Charles E. Pellew that appeared in The Craftsman in 1909. The magazine promoted the tenets of the Arts and Crafts movement—opposition to mass manufacturing and reverence for handiwork and the value of human labor—by sharing techniques for crafting (in every field from woodworking to needlepoint), profiling trade schools and makers, and offering essays on the virtues of do-it-yourself. Pellew’s article “Tied and Dyed Work: An Oriental Process with American Variations” recognized Indian dyers as the originators and perfectors of many tie-dye techniques. Pellew also praised examples of tie-dyes made with modern, Western materials and designs. “It is indeed doubtful,” he writes, “whether we have any process at our disposal that compares with this in simplicity and economy, as well as in beauty.”

Only a few months before Pellew’s article was published, a feature in Harper’s Bazaar titled “Gobolink Tapestry” presented techniques for tie-dyeing.” (The author was Adelia B. Beard, cofounder of the first American girls’ scouting group, best known as the Camp Fire Girls.) The term gobolink was likely borrowed from the title of a popular inkblot game, in which players made symmetrical inkblots (not unlike those used by Rorschach for his psychological tests) and then created amusing rhymes based on the resulting patterns. But gobolink was also used to denote anything uncanny, odd, or seemingly magical—as well as things considered foreign or other. This latter meaning colors Beard’s opening paragraph, where she patronizingly (and prejudicially) refers to the nonstandard patterns of tie-dyeing as “freely barbaric as the work of savages,” and fails to recognize the skill and precision which characterized many traditional forms of tie-dye technique. By presenting tie-dye as an exotic, uncontrollable, unconscious process, Beard encourages her American readers toward self-expression but strips away tie-dye’s real historical and cultural contexts.

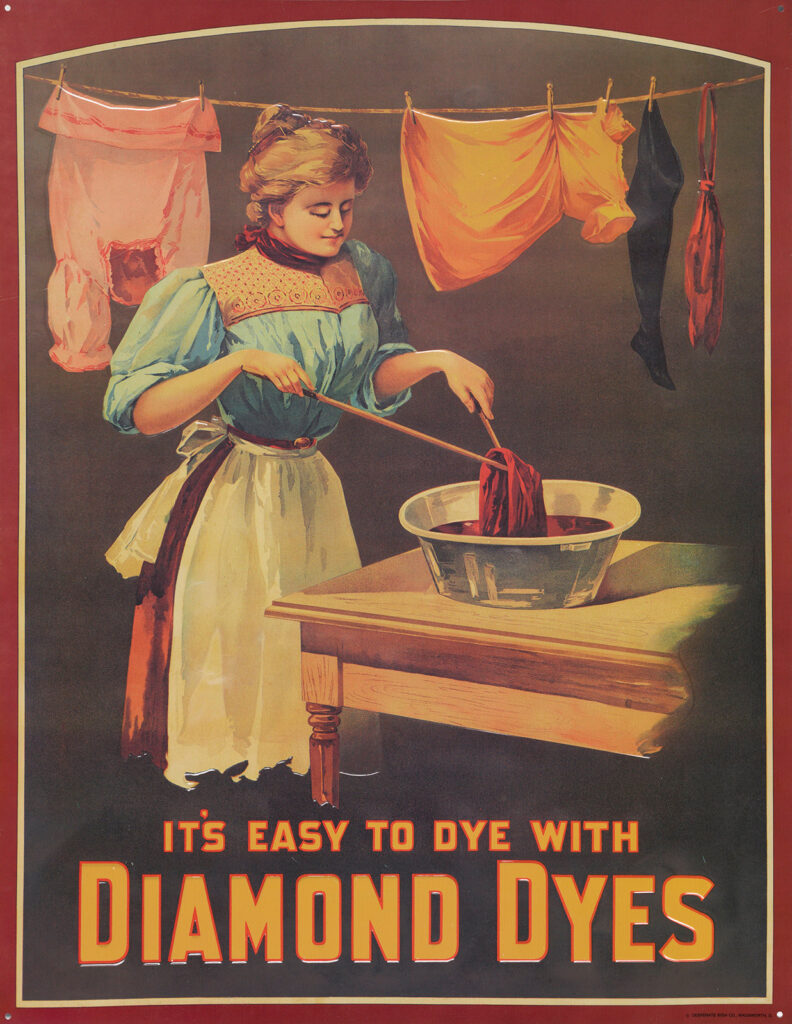

The truth is dyeing clothing, curtains, upholstery fabrics, and other pieces of decor at home was already a longstanding American tradition and one that allowed budget-conscious homemakers to refresh their surroundings without spending money on new items. One of the most important factors in selecting dyes was their ease of use: the fewer steps and less complicated chemistry required, the better. One popular 19th-century brand took simplicity as their tagline: “It’s easy to dye with Diamond Dyes.” An advertising sign from around 1890 depicts a woman dyeing a variety of clothes—a child’s dress (likely cotton), and a pair of stockings (silk or wool)—emphasizing that Diamond Dyes could be used on a wide range of fabrics.

In reality, the quality of early-20th-century home dyes varied greatly, and many produced poor or less durable color results. Pellew stresses the importance of choosing quality dyes in his article. “I should doubt,” he writes, “if the . . . Salt Colors sold in packages at the druggists would be fast either to light or to washing.” He instead recommends “sulphur” colors (manufactured with hydrogen sulfide in a high-heat baking process), which were invented and popularized in the 1890s. Fumes from sulfur dyes, however, could be noxious, and their high reactivity meant they couldn’t be used in copper, brass, or iron vessels. For the home crafter of 1909, tie-dyeing could still lead to frustration and mixed results.

In Pellew’s time, virtually all dyes used in the United States came from Germany, then a powerhouse of the Atlantic chemical trade. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914 came blockades, and with blockades came shortages in the United States of many common goods—including dyes and synthetic colors. But American color chemists quickly responded, and the market was flooded with new dye products, some of a higher quality than others. For home dyers, one of the most popular new options was RIT, an inexpensive “direct” dye that debuted in 1916.

Direct dyes addressed the uneven performance home dyers often encountered. Earlier “salt” or “acid” dyes were best for wool and silk, as the dye molecules and natural proteins in the fibers shared a chemical affinity that allowed them to bond more easily. But acid dyes didn’t work well on plant-based fibers, such as cotton and linen, which required mordants and processing to hold the color. Direct dyes got around these problems by combining two types of dyes: those suitable for cotton and linen as well as those suitable for wool and silk, meaning they could be used on nearly any fabric with relative ease. Their universality quickly made them a consumer favorite.

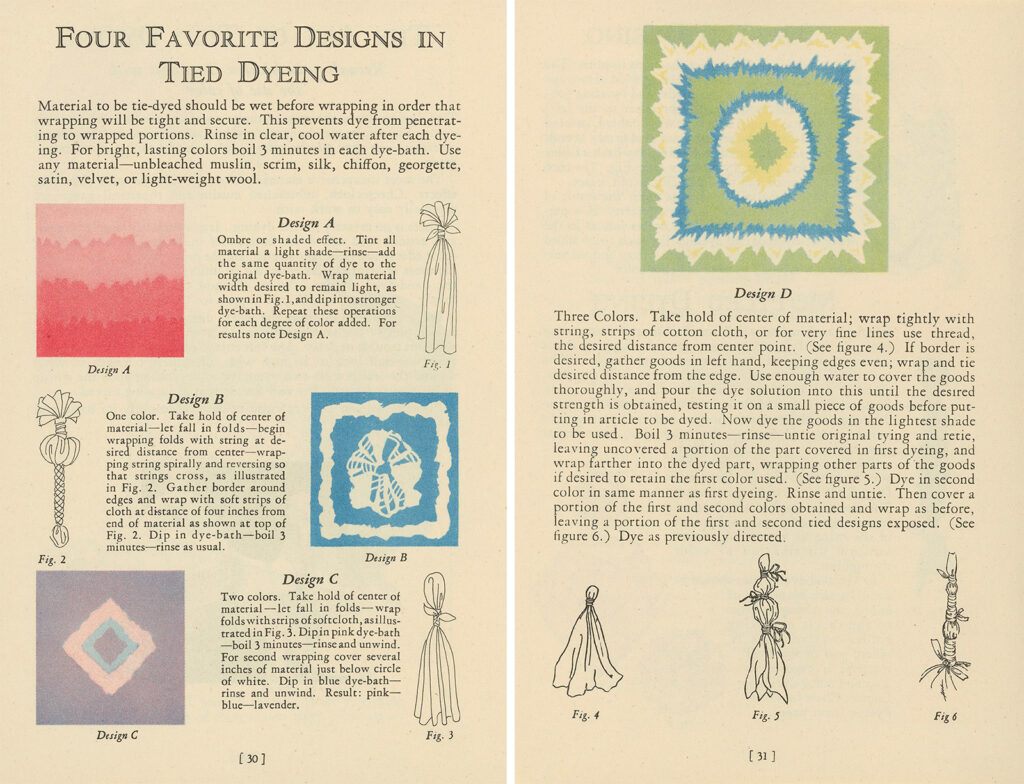

A 1928 informational booklet, The Charm of Color, showcases things a crafty home dyer could do with direct dyes. Alongside instructions on bleaching, cleaning, and dyeing silks, wools, rayons, and other common fabrics, it offered guidance on “modern” home decor, fashion, and color matching. But the highlight is a section titled “The Art of Tied Dyeing.”

The pamphlet shares four methods for creating “tied and dyed” designs: a shaded ombre effect, a one-color circle design, a two-color design, and a more complicated three-color process. Readers were instructed to work from the lightest color to the darkest and to boil the fabric in the dye bath. Other methods for “mottled” and “twisted” dyeing were included as variations on the traditional tied technique.

During the 1920s and 1930s, tie-dyeing was promoted as an especially suitable and fashionable hobby for thrifty, sensible women. In the United Kingdom, tie-dyeing was even featured on the big screen as part of Eve’s Film Review, a series of light-hearted, educational silent films directed at women. The series’ 1933 lineup included a short called “Tied Dyeing—A New Art for the Home,” showing the “fascinating and economical” transformation of a boiled silk scarf into a stunning à la mode wrap.

American women of the same era recognized the appeal of refreshing tired fabrics with new, vivid patterns—thanks especially to inexpensive dyes—and tie-dyeing saw a brief surge of popularity during the Great Depression. Sadly, few Jazz Age tie-dyes have survived with their colors intact, casualties of the poor fade-resistance of many American dyes from that time.

But the appeal of home dyeing has endured. RIT dyes are still sold, and in an even more dazzling array of colors. (Other improvements have been more consequential: nearly all common do-it-yourself dyes once contained benzidine, a carcinogen that’s since been banned.) Tie-dyeing, briefly popular in the 1920s and 1930s, and widely beloved in the 1960s and 1970s, has made a resurgence, along with other nostalgic hobbies, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unique, handmade, and affordable, the marriage of ancient techniques and modern materials still showcases the true “charm of color.”

The author would like to acknowledge the resources provided by the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists in creating this story.