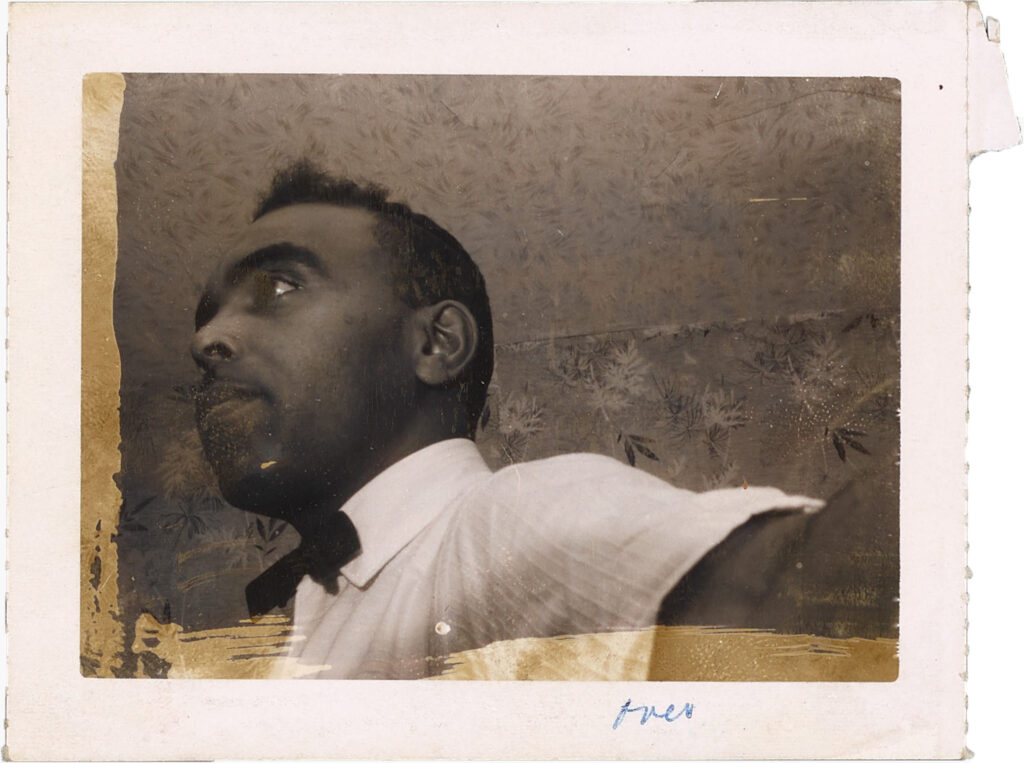

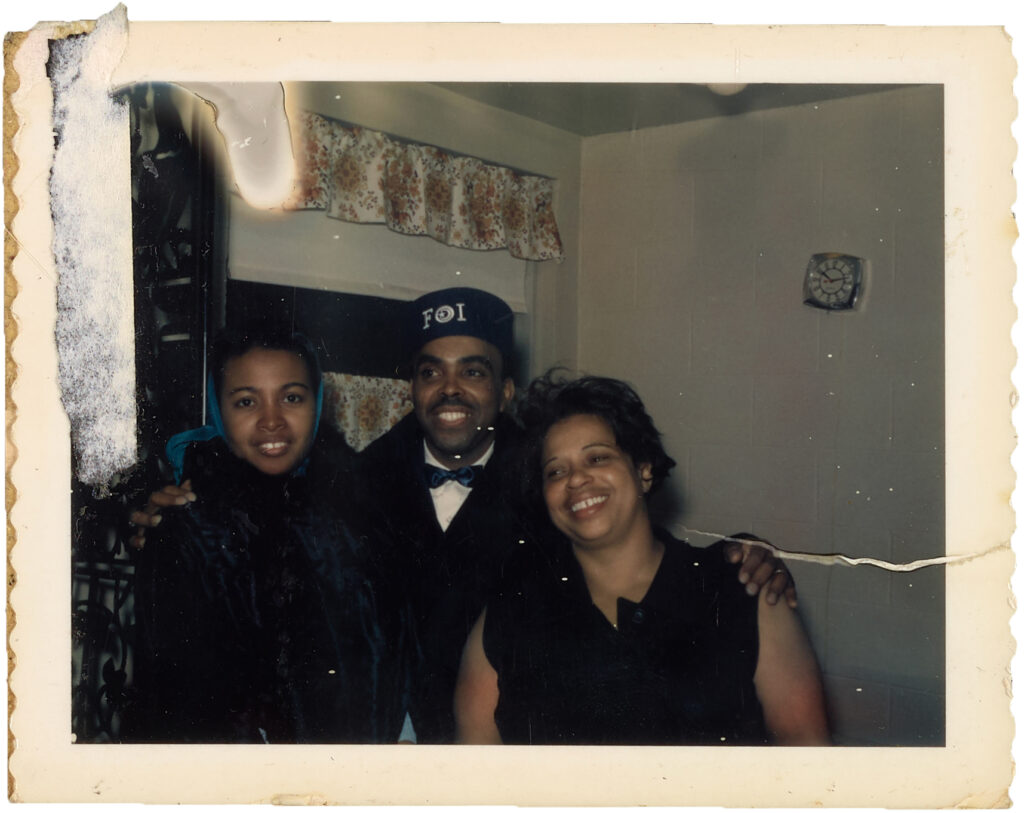

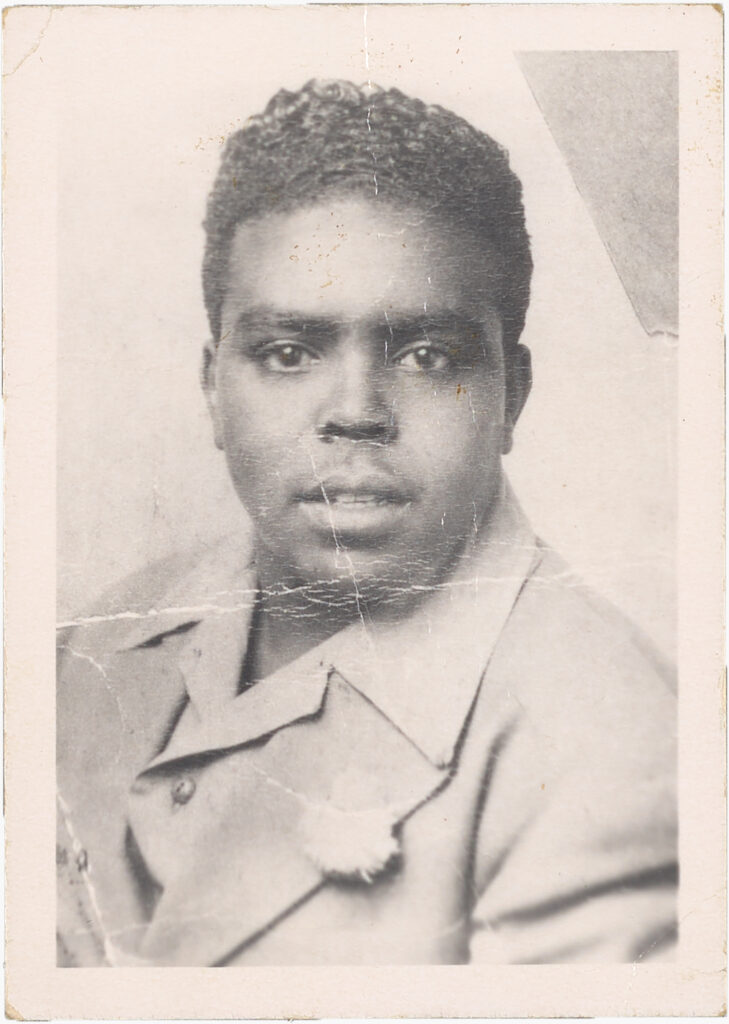

John Scott is the kind of man who prefers to catch and clean his own fish. My nana calls him a street person, especially when annoyed with him. However, this irritation cannot hide her smirk and cute eye roll of reluctant approval: that’s her street person. Ever since retiring from his dual careers as an army-trained welder and a Muslim minister, my poppy has worked outside. If he can use his hands to make or save money, he will. The more informal and messier the work is, the better. He melts coins into gaudy jewelry and trims down short-brimmed hats from long-brimmed ones.

While my poppy could still walk and drive the streets, he hacked, driving people home from ShopRite and other grocery stores in and around Germantown, Philadelphia. This was when Philly was black on all sides. Before Uber and Lyft and before the police labeled hacks “illegal taxis”; before gentrification altered how black people could support one another. Before COVID-19, a street person like my poppy could drive you home with your groceries and even sell you freshly caught and cleaned porgies (Stenotomus chrysops) on the way. Some people call this fish scup, menhaden, or sea bream, but in Germantown in the early 2000s, one might have still heard “porgies for sale” echoing in the parking lot.

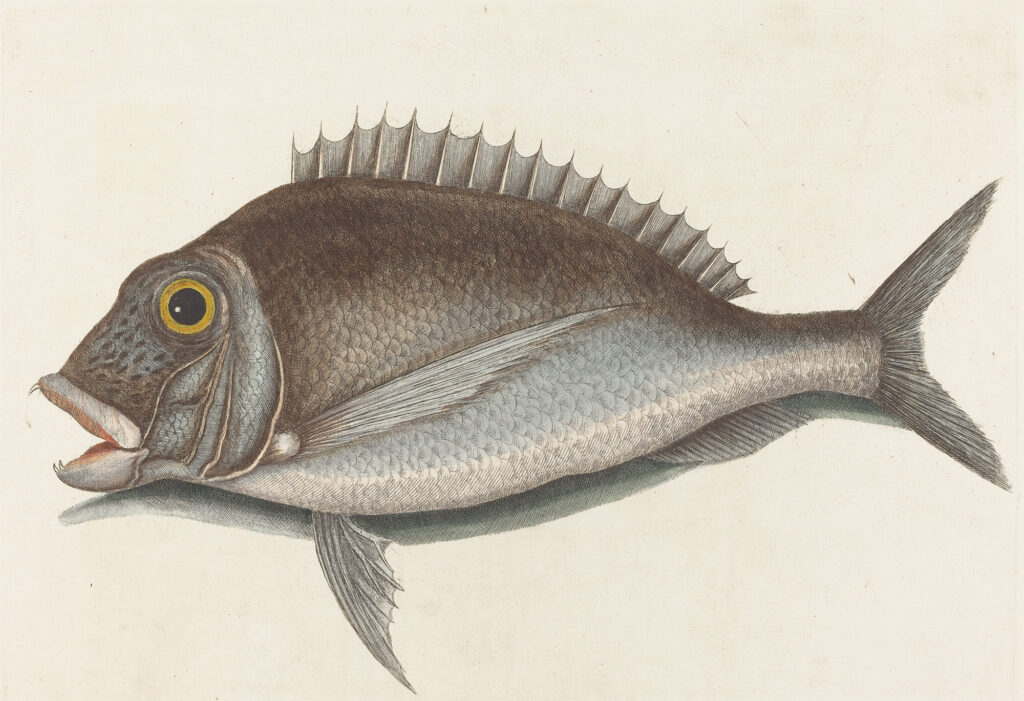

The porgy is no prize fish. Commercial fishermen and chefs often label them “bycatch” or “trash fish” because they are so easily caught in the wild that anyone could do it by accident. But, ironically, not everyone can prepare porgy. Cleaning and eating them at home takes patience. Each fish has about as many bones as the species has breeding grounds along the Mid-Atlantic Bight from Massachusetts to North Carolina. Maybe the species’ abundance and boniness convinced the Narragansett and Abenaki people to scatter porgies on agricultural plots as a fertilizer. One source actually insists that the word porgy comes from Abenaki words for fertilizer, pookagan and poghaden. However, other records suggest that the terms scup and porgy are colonial reductions of the Narragansett word scuppaug. For John Scott, porgies mean everything.

My poppy loves his porgies coated in cornmeal, panfried, and served with two condiments: sliced white bread and hot sauce. He eats his fillets carefully while listening to something on the Discovery Channel or Entertainment Tonight. After removing the most visible bones with a fork, his tongue rubs the insides of his lips and cheeks to double-check before any chewing happens. Cleaning and then eating around these tiny, translucent bones takes skill. Scarf down a porgy fillet too quickly, and a bone will remind you to slow down. Its flaky texture profile might resemble snapper, but it has far too many bones for salad, sushi, and inattention. Chefs in the northeast historically considered porgies too commonplace and industrial for restaurants, but watching my poppy eat one with his mouth open to spit out bones makes you think maybe it’s a fish best eaten in private.

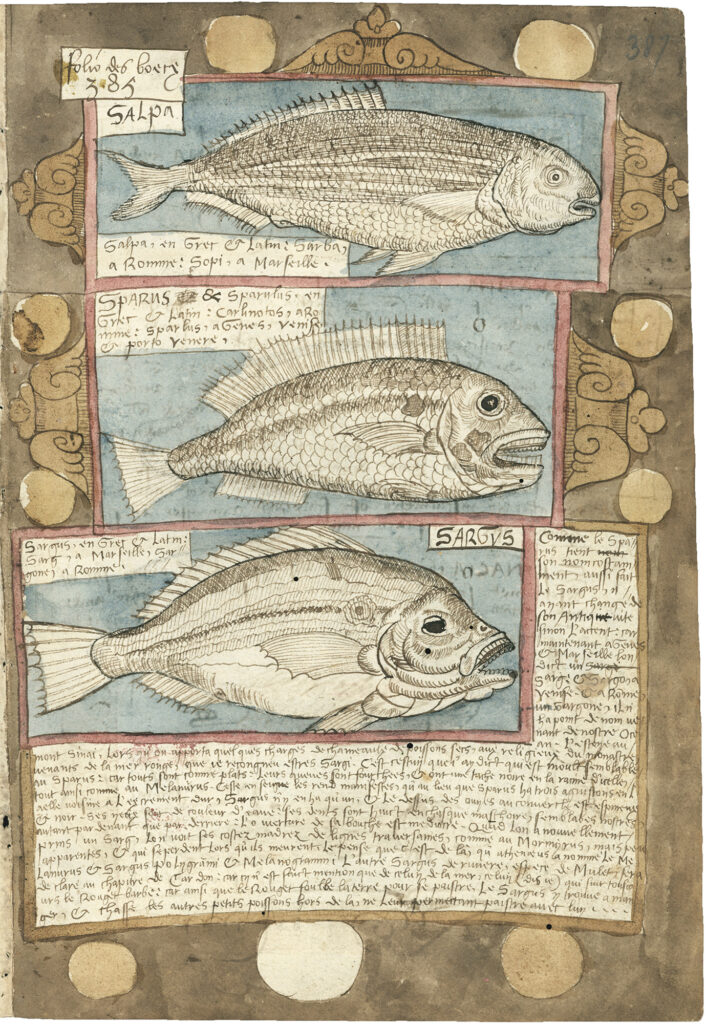

Eating porgies at home is a global pastime. People fish over 150 species in the porgy family (Sparidae) in temperate and tropical waters worldwide. Each species varies in size and color, but Sparidae shares many features: singular dorsal fins, shallow-water habitats, and small mouths with strong, molar-like teeth for eating hard-shelled invertebrates.

Their affinity for eating crab and mussels gives the porgy family their distinctive sweet and shrimplike taste. The South African black musselcracker (Cymatoceps nasutus) is a popular sporting fish that can reach over 100 pounds in weight. But most Sparidae, like the Stenotomus chrysops that my poppy catches, do not exceed a foot in length or a pound in weight.

These smaller varieties have many colloquial names because so many people eat them. Japanese fishermen call them tai. Settlers in Australia and New Zealand tend to call their porgies snapper, following a tradition of colonial misidentification that goes back to Captain Cook in 1770. But since this porgy (Chrysophrys auratus) inhabits coastal waters from the Philippines to Indonesia, it likely has countless Indigenous names. To paraphrase my nana, Māori people have used the word tamure since before Captain Cook was born. Maybe even as long as the Dharug people of Southeast Australia have referred to them as wollamie.

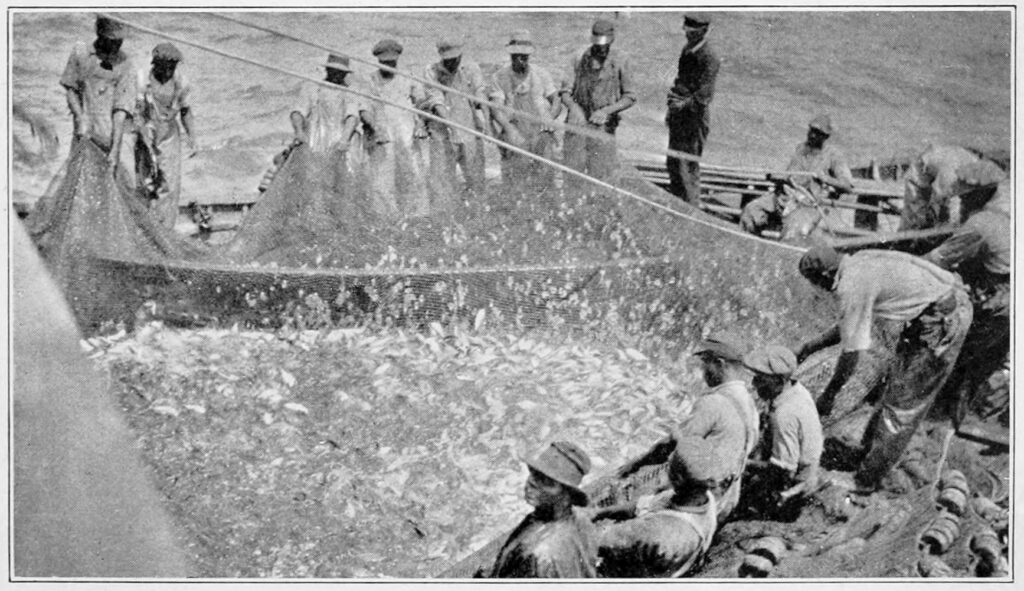

Nineteenth-century industries tried to fasten even more names to porgies. Machines broke Stenotomus chrysops down into oil, bones, and scraps to make lantern oil, soap, and fertilizer. New England settlers built entire fisheries, with porgy steamers and porgy factories, to make porgy products. Since the days of salting porgies and sending them to Caribbean plantations to feed enslaved labor, northeastern fisheries have imagined great wealth in drying porgies.

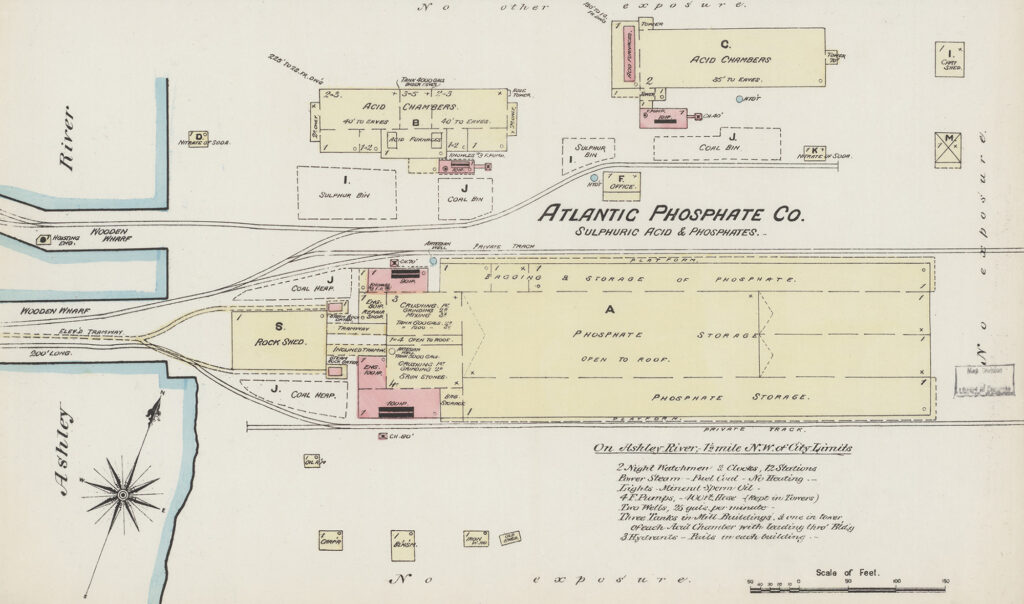

Building on Indigenous methods of using porgy for fertilizer, the Quinnipiac Fertilizer Company secured a patent in 1852 for drying fish scrap by solar heat, and used this technique to produce enough fertilizers for plantation owners in New England, southern states, and the Caribbean. Soon, the Pacific Guano Company of Boston started using dried porgy to supplement dwindling bird guano supplies and meet increasing demands for fertilizers. After the abolition of slavery, southern cotton planters adopted these chemical solutions to replace enslaved labor, and the Boston company found great success mixing dried porgy with phosphates from South Carolina.

But not for long. Fisheries, big and small, never fully understood or controlled porgy behavior. Porgies’ sexuality does not map well on spreadsheets, table graphs, and economic forecasting. Many porgy specimens carry male and female organs simultaneously; others change sex as they mature. Their breeding tendencies often didn’t look like tendencies. Some years waters overflowed with the fish, but then they could disappear for decades at a time. Rachel Carson wrote that porgy became one of the most important industrial fish, especially for fertilizers, but with a history marked by “severe fluctuations in the catch.”

Big companies could outlast this uncertainty, but most fishermen went bankrupt betting on porgies. According to the leading contemporary scientific journals, thousands of black fishermen also made careers in fisheries in the 1870s and 1880s. Numbers decreased drastically by the 1890s. The professionalization of the industry excluded them. Black-operated fisheries likely also struggled to weather porgy droughts, but records do not tell their full story. Black fishing people, especially those outside of formal fisheries, were as illegible to the industry as porgies. On black fishing, journals usually quoted the Smithsonian Institute’s foremost expert on fisheries, George Brown Goode, who admitted that “the negro element in the fishing population is somewhat extensive. We have no means of ascertaining how many of this race are included among the native-born Americans returned by the census reporters.”

Novelist DuBose Heyward actually knew black fisherman from growing up in Charleston. In 1925, the year before my poppy was born in Alabama, Heyward published Porgy. It describes how black fishermen discharged “strings of gleaming whiting and porgy” and how black stevedores loaded boats. It remembers black folks living near the Boston company’s fertilizer mills where they worked and how they “stank intolerably,” and how others worked in nearby phosphate mines after cotton season. Porgy also offers readers a glimpse into the picnic and parade culture of black folks in Lowcountry South Carolina. Heyward illustrates places where the “earth had cared for” us; where the creeks shared fish, crabs, and oysters and the forests had berries and palmetto cabbage. Fishermen were not central to this story of black recreation, but Heyward’s novel does underscore the centrality of rivers and oceans to black senses of freedom. Without even highlighting Sparidae fishes, Porgy helps us imagine the liberatory role of porgies across the African diaspora in the Americas.

From the Gulf of Mexico to Colombia, coastal black and Indigenous communities have fished varieties of porgies for centuries. Like their relatives in the Pacific, some red porgies (Pagrus pagrus) in tropical American waters have a “snapper” problem that goes back to the colonial period. Other types of Pagrus are common in West African waters and might have even provided enslaved African people in the Caribbean Basin with a rare sense of familiarity. In any case, porgies were likely vital food sources for black peasant and fishing communities in the wake of slavery. Red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus) gets all the attention, but look closely at Haitian, Jamaican, and Cuban cookbooks, and you will see dishes designed for porgies. Consider this: if white settlers historically considered oysters, clams, and mussels poor-quality foods for black and Indigenous consumption, then shellfish-eating porgies that inhabited the shellfish ecosystems were some of the most accessible fish to black and Indigenous communities.

The abundance and catchability of porgies add to their accessibility. Porgies do not swim into deep waters or stray too far from the continental shelf. They avoid traveling too far from their prey, concentrated in coastal reefs and bays, shallow seafloors, rocky outcrops, and mussel beds. Porgies seldom move in solitude but prefer migrating in loose, multispecies schools of similar-size fishes. Finally, porgies generally lack finesse. They do not nibble gently at the bait but instead attack it frantically and forcefully as if it were a mussel fastened to a rock with its mollusk foot. Use tough and rubbery bait like squid strips, and it won’t take long for a porgy to try to yank it off. If the temperature and location are right, my poppy does not need more than a few hours to catch 50 porgies.

John Scott fell in love with the ocean when he moved from Alabama to Atlantic City during the Great Depression. He does not remember selling ice cream as a teenager on the boardwalk as a chore. He heard and saw the ocean all day. He tasted the ocean, too. This appreciation of fresh seafood continued when he relocated to Philadelphia to work as a welder after World War II. If anything, his love for fresh fish only grew stronger after he converted to Islam and stopped eating pork. Bless my nana because my poppy is a generational talent at picky eating. He’s the kind of military man turned minister who shaves daily, cuts his hair every three days, and always takes an hour to get dressed. He would not hesitate to whine about lousy fish. To avoid him complaining about the quality of fish, my nana probably agreed to cook only what he bought or caught himself. He was a regular at the big fish markets in South Philly, but after retirement, he preferred to fish with his friends.

For black folks, staying connected to the ocean is often a community affair. In the 1970s black-owned fish trucks sold residents in North and West Philly fresh porgies and other fish. In 2018 ecologist Talia Young started a community-supported fishery called Fishadelphia to provide fresh fish from local fisheries to “culturally and economically diverse seafood eaters.” They buy what’s available on the docks to offer members seafood tied to their own traditions. My poppy operated at a much smaller scale from the 1980s to the 2010s and organized short fishing trips to Cape Cod with a group of elderly black men called Three Strikes You’re Out. Commitment to each other was paramount. Their goal was not necessarily economic. They did not see their effort as social justice. These frugal older men just wanted to fish and sell enough porgies to pay their way.

My annual summer visits to Philadelphia coincided with these fishing trips and the return of Stenotomus chrysops to coastal waters. After wintering along the mid and outer continental shelf, adult porgies form schools with various, similar-sized species in the spring and migrate inshore. The ritual for my poppy’s return to the ocean with his kindred spirits goes as follows: select a date, pack the coolers with ice, pick up Dunkin’ Donuts, and meet at the charter bus before midnight. Once at the bus, this pack of 20 or so retired black men and their progeny load the bus with coolers and fishing rods and begin to make their way to Cape Cod.

The sound of seagulls signals our arrival. It’s hardly 6:00 a.m., but it’s bright and light blue on the pier. From there, things move quickly. Each poppy finds his favorite spot on the boat, sets up his station, and prepares his bait as the captain embarks for deeper waters. But not too deep. The goal is to find a shallow feeding ground inhabited by mussels, sand dollars, and schools of porgy. The vast seascape looks just like flat water to me, but the captain combines his radar and memory to envision a whole world underneath us. The boat picks up speed and moisture. The air feels hurried and is sprinkled with crusty salty water. Then the boat shakes to a stop, and the air goes still and quiet. Without the ship engine rumbling, you can hear the few seagulls that followed the boat signal our arrival again. Fishing starts around 6:30 or 7:00.

The narrow deck that wraps around the boat gets bloody and slick. The first fishing lines cast catch porgies within seconds, and a veritable fish frenzy erupts within minutes.

Porgy fishing is all drama, no suspense. The fish are aggressive anglers that bite recklessly at bait with little strategy or ruse. We pulled up so many fish in two hours that one might think the schools of fish were visible in the water. But they weren’t. Look out across the water—you’d think we were in the middle of the ocean. Only seagulls’ calls and fish flip-flopping in buckets give you a sense of the biodiverse feeding grounds below the boat. Catching the occasional flounder is another reminder of this shallow-water habitat. The captain might relocate the boat to three or four feeding grounds depending on the weather and water temperature. But one or two can provide enough porgies to fill all coolers. Fishing ends around 10:00 or 10:30.

Most of the ride back to the pier and then back to Philly is just older men bragging about whose grandson or nephew caught the most porgies. During our long stretch home, my 20-porgy haul became a story about me catching 40 porgies. My poppy was so happy to lie and say he caught no fish at all.

At home, he wastes no time cleaning our 40 or so fish. Porgy is a particularly smelly species, and cleaning any fish is messy, so this is an exclusively back-porch activity. And it can be tricky on a late afternoon in Philly during the summer. Without letting the fish drop below 40 degrees, my poppy rinses and descales each fish. Scales fly everywhere. Some stick to his forearms and add glisten to the jewelry he made from coins. He removes their guts, gills, and heads, then places the fillets in bags and back on ice. If he was lucky, he found some fish eggs to save for my nana, who insists he (her street person) cleans porgies just like his mother cleaned porgies. With the freezer filled with enough fish to last a month, my poppy repacks his cooler with most of the remaining fish. He leaves a few fillets for us to eat for dinner and then heads to ShopRite to sell the rest.