Illustrations by Sarah Kaizar

When we exited Circuit City, we entered a different climate than the one we had left an hour earlier. My sister doesn’t recall why we were in the last Circuit City in Tucson, Arizona. Neither does my dad.

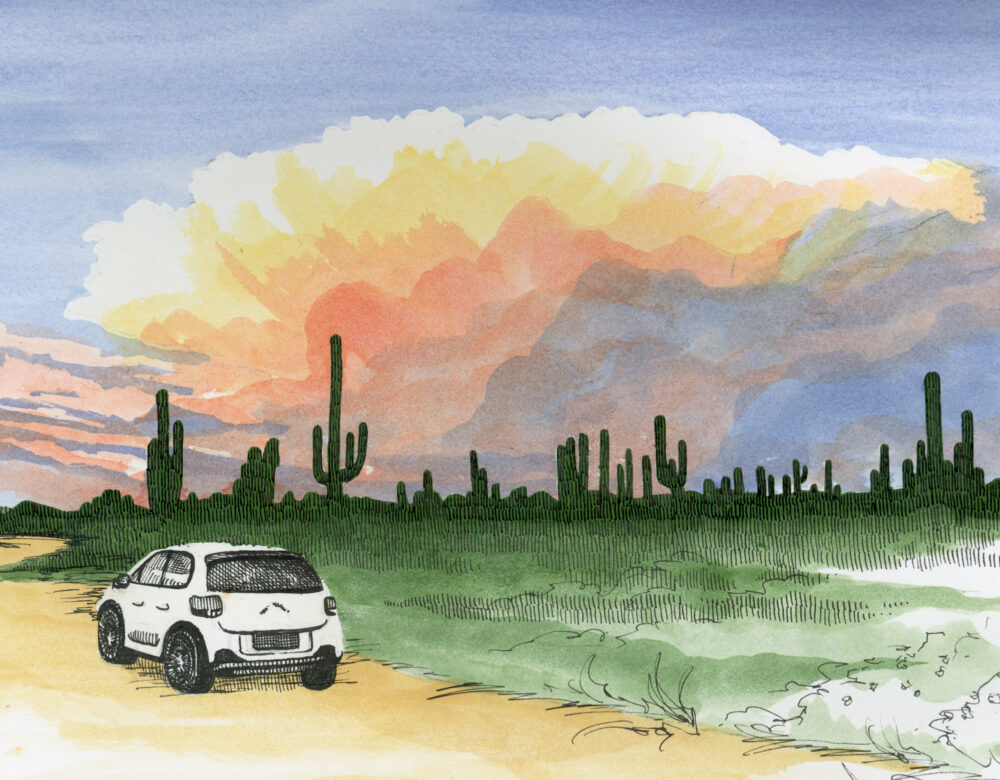

We mostly remember the 40-degree dive in temperature that afternoon—from around 110 to 70 degrees—and how eerie it felt. It looked and sounded eerie, too. There’s no forgetting those charcoal-colored clouds that swelled and snarled in the sky until they became the sky. The kind of noisy clouds that produce enough intracloud and spider lightning to muffle distinct bellows of thunder into a steady grumble. Growling clouds whose gruff chatter sends the most unambiguous message: go home if you can.

Where do hummingbirds and butterflies go when it is about to rain this hard? What about unhoused people or migrant travelers without documents?

We hardly reached the car before the sky cracked. During rainy car rides, we, like most children, enjoyed watching raindrops merge, split, and inch across the backseat windows. Not this ride. Monsoon raindrops did not offer the same cute and animated experience. These drops fell from the sky like they had something to prove.

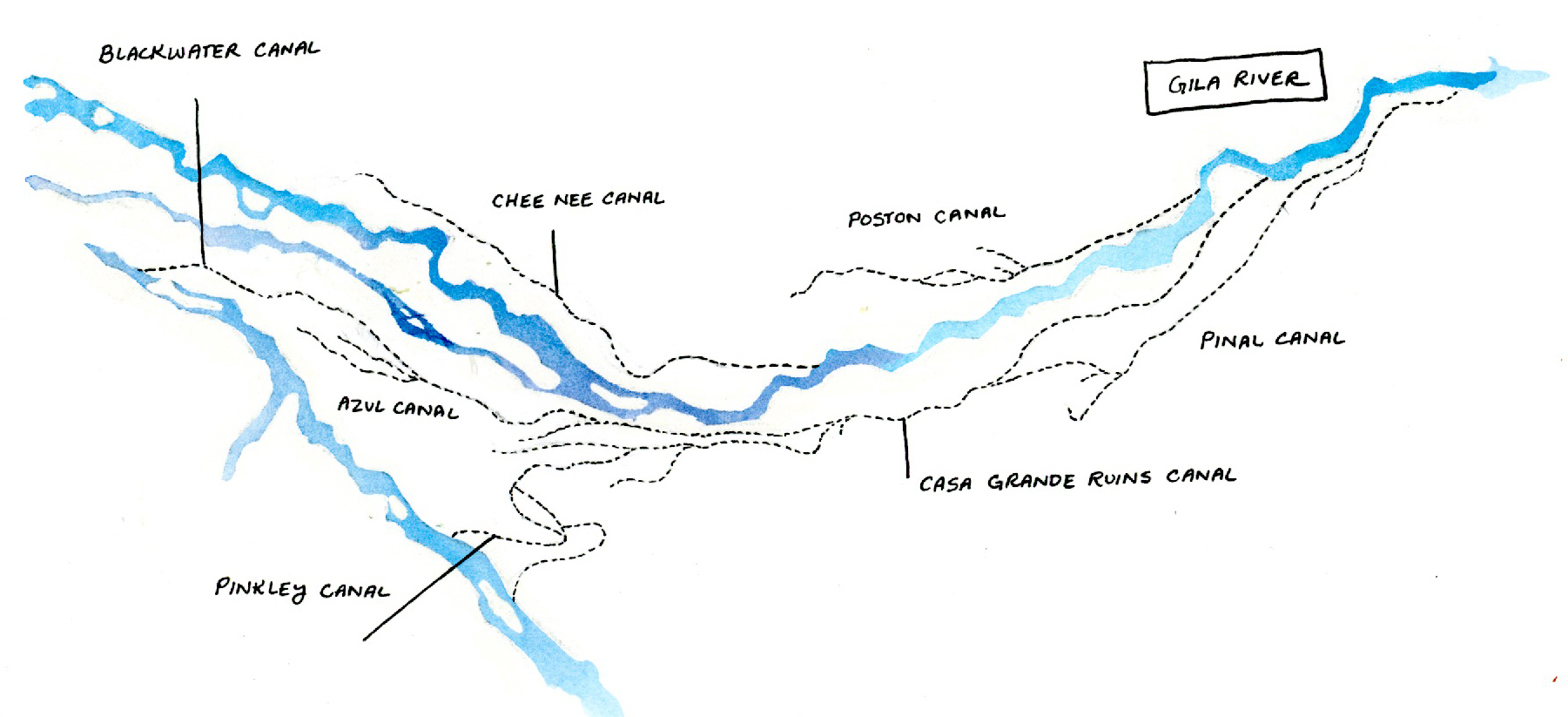

It must have been late July or early August, the Sonoran Desert at its hottest, the rising heat drawing massive thunderstorms from the east. After a long journey in water-saturated air masses that formed over the Gulf of Mexico, these raindrops plunged 2,500 feet at 20 miles per hour before bursting into white water against cars and concrete. Literal tons of monsoon rain pounded on impermeable desert hardpan and ran off into one-shot streams that added division to the long-standing watershed. Only when these heavy raindrops reached the soft, contoured desert sand in mass did they gain momentum and form flashes of a river that coursed through the landscape until it became the landscape.

Monsoon rivers in the Sonoran Desert might last only three hours. But that’s enough time to deposit concentrations of moisture and nutrients in dry floodplains called desert washes. In harsh, semiarid regions, annual monsoons inform where, how, and when most life, struggle, and biodiversity occur. A friend from Mumbai calls Tucson thunderstorms “discount monsoons.” But, by creating washes, these sporadic and isolated rains arguably do in hours what monsoons in India do in a season: shape land, ecology, culture, and power.

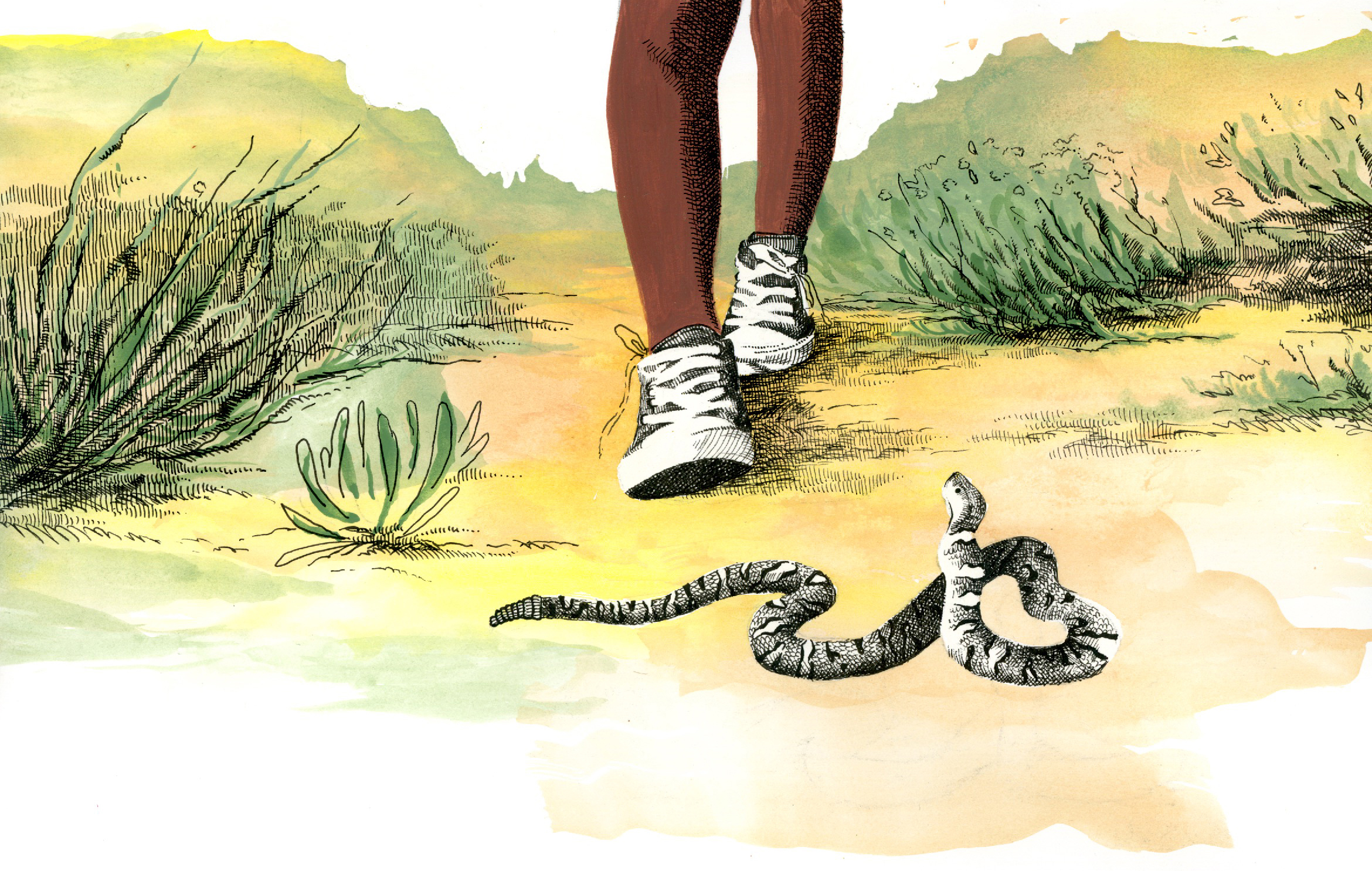

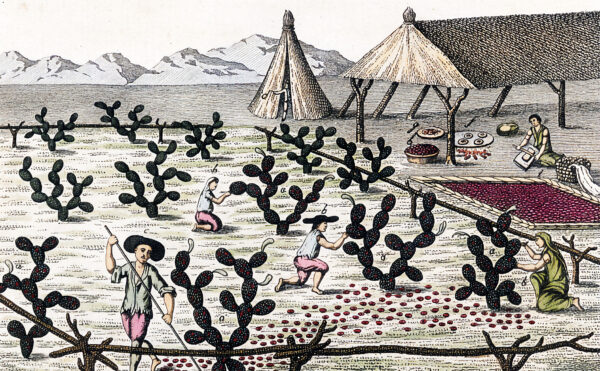

Most Tucsonans refer to any cacti-filled scrubland between properties as “the wash.” However, to the Tohono O’odham, the ak cin is more precisely the “mouth of the wash.” Ak cin farmers know the mouth of the wash as small, seasonal floodplains that “harvest and concentrate water, nutrients, and seeds from watersheds to support greater densities of life.” In the regions northwest and southwest of Tucson, Tohono O’odham, Pima, and Hopi communities practice what their ancestors perfected over 3,500 years ago: planting desert cotton (Gossypium thurberi) in irrigated desert washes.

Ecologically speaking, the desert wash is a dry riparian habitat—a hardy community set on the shores of a temporary river. Heraclitus believed a person can’t step in the same river twice—but how did he define river? He believed a river is not one thing but a collection of parts in movement together. To Heraclitus, you step in a moving river once because your next step is in another constellation of different moving parts that merely resembles the same river.

Would Heraclitus imagine a desert wash as a river you can step in twice? A desert wash does not move or change dramatically. Its sandy, gravelly parts do not shift quickly with each step. But neither is a desert wash one unvarying thing, static nor singular. It’s the living afterlife of—or, maybe, the second step into—an everyday monsoon. And its thingness embodies a confluence of quotidian, occasional, and infrequent tensions akin to what Christina Sharpe describes as life in the wake of slavery. A living landscape that holds onto a few days of torrential rain is deeply uneven.

Few things concentrate wealth and resources like desert washes. As ribbons of relatively moist microhabitat, this terrain occupies tiny percentages of the desert landscape but significantly influences how life takes place in the greater watershed. It’s a place that divides haves and haves-not with granular clarity.

Why did settlers see the desert and envision a controllable oasis for colonialism to grow? What did settlers misread or fail to see?

In the wash of monsoons—and the struggle of species to survive there—we see the effects of concentrated wealth and resources in increasingly warmer and drier environments and how different species of plants and animals evolve to thrive in these gaps in land and rainy seasons. We can question how humans have embraced desert washes to reinforce violence against plants, people, and places. And we wonder why white settlers imagined using black labor and foreign seeds to establish cotton plantations in Arizona where generations of ak cin farmers irrigated wild cotton in desert washes. Scientists and scholars are still learning what the ak cin farmers always knew: so much life—biology, biodiversity, and biography—emerges from holding onto what you can.