In the mid-17th century, stories of an alchemist known as Dr. Butler gripped some of the world’s brightest minds. Who was this Dr. Butler, and were the rumors about him true? Could his concoctions really cure all diseases and fill his pockets with gold?

Butler boldly claimed to possess the philosophers’ stone—an alchemical substance that, among other things, could purportedly turn base metals into gold or silver. Such claims intrigued an international network of esteemed scientists, and throughout the 1650s and 1660s they sought to learn whether he had discovered the powerful substance. To prove (or disprove) his claims would require Butler’s full recipe and the re-creation of his process by the scientists. Such attempts to validate alchemical claims were an important part of early modern science, and they helped build the foundation for how we communicate and document science today.

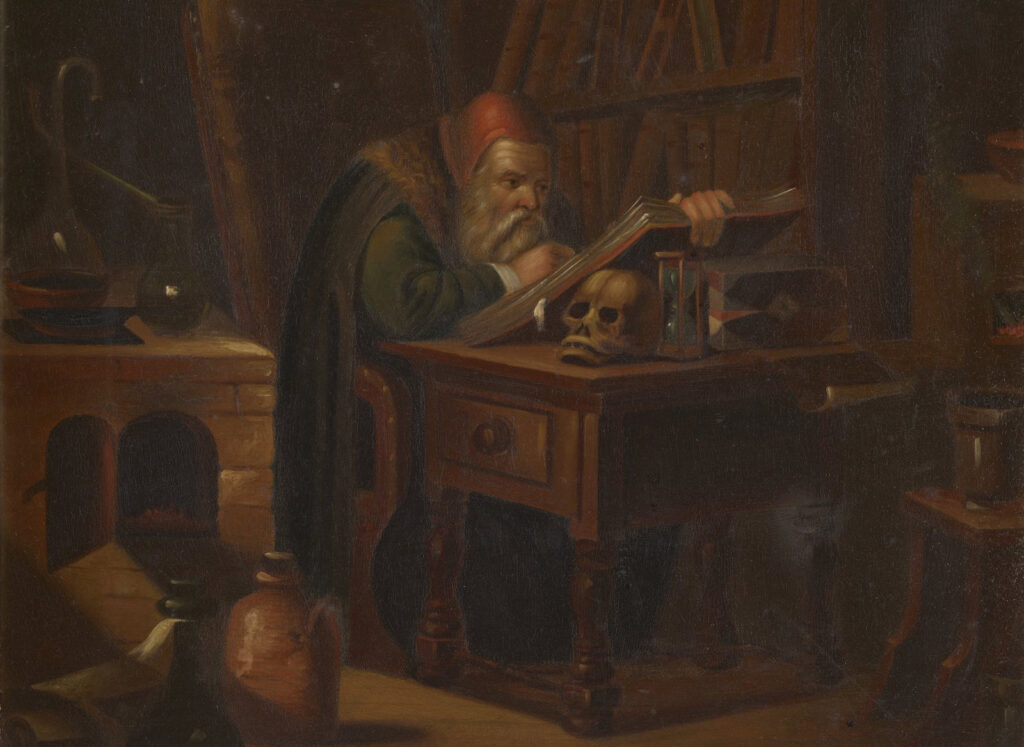

During the 16th and 17th centuries, a period commonly known as the Scientific Revolution, European experimentalists were busy testing and refining older theories and practices. Alchemy, with its long and distinguished history, preoccupied some of the greatest minds of this time. Its emphasis on understanding natural substances and producing material changes made it a central component in efforts to improve medicines, advance agriculture, and develop commercial trade industries.

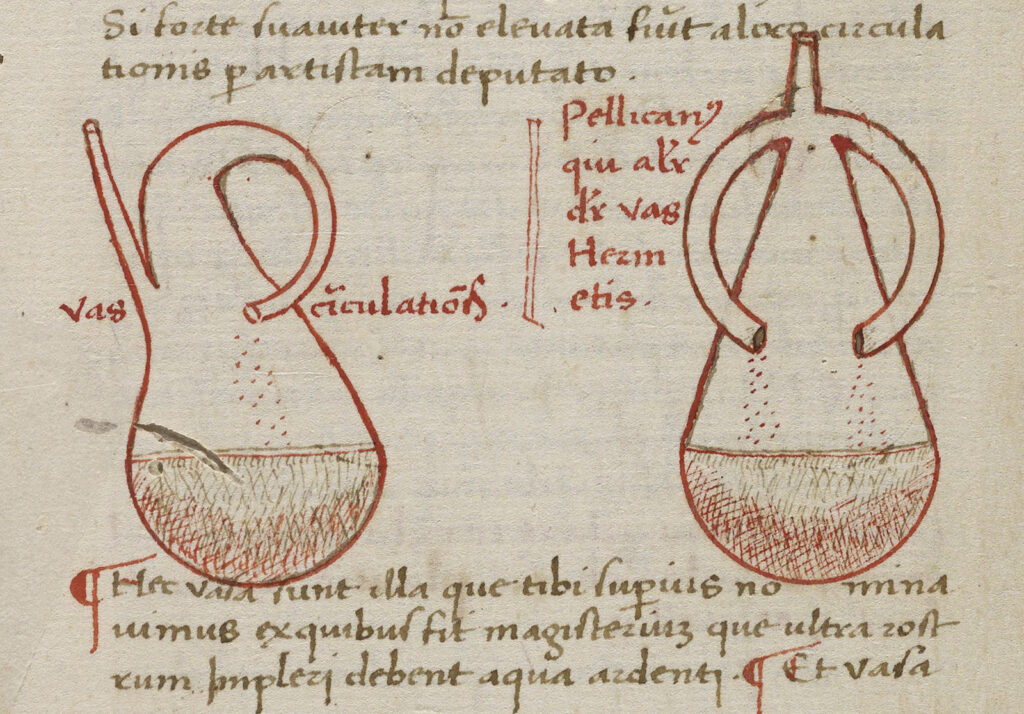

The search for the philosophers’ stone was only one part of a much larger quest for alchemical knowledge, though a significant part. Seventeenth-century chemists were already able to produce many material changes in their stills and alembics, ranging from distilling alcohol to separating metallic compounds. If adding a small amount of rennet would coagulate milk into cheese, was there an equivalent substance that could coagulate molten lead into gold? Both contemporary theories of matter and observational evidence suggested such a substance could exist.

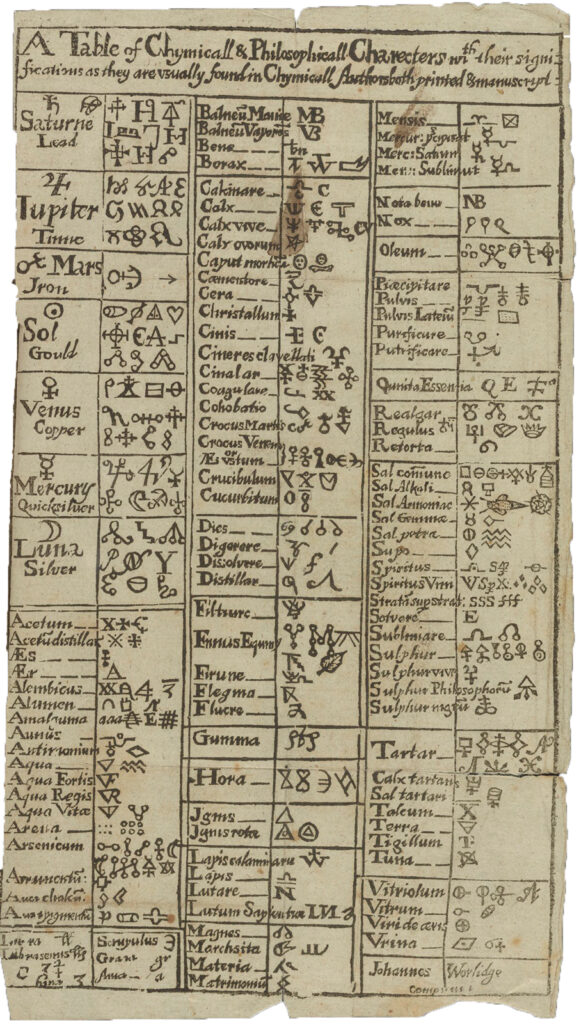

But trying to create a philosophers’ stone turned out to be no easy task for these chemists. The first problem was secrecy: most early alchemical texts hid their knowledge behind drawings, symbols, and metaphors. While this secrecy could hint of deception and greed, there was also good reason for this discretion. Imagine the impact on the economy if anyone could turn rusty iron into gold.

Butler’s story circulated at a time when scientists were trying to decipher alchemical texts, to better understand the materials and processes described in their cryptic language and imagery. These chemists also were eager to establish their own reputations as trustworthy experts and to share information about individuals, such as Butler, who might be hiding valuable knowledge.

So, when Butler claimed to have deciphered nature’s great secret, his claim was worth exploring, at least until it could be proven false.

One of the earliest accounts of Butler was given by a Flemish chemical physician named Jan Baptista van Helmont in his compendium, Ortus Medicinae. Published in 1648, four years after van Helmont’s death, the book offers a lengthy advocacy for incorporating chemistry into medical theory and practice, an approach that was not yet commonplace. In his book, van Helmont claims to have befriended a “certain Irish-man called Butler,” and he offers some suggestions as to the metallic and chemical properties of Butler’s “certain little stone.”

One decade later Henry Oldenburg, a curious and learned German living in England, procured from a French scientist a more substantial recipe for Butler’s stone. This recipe was based on the Frenchman’s attempts to re-create van Helmont’s vague instructions. Oldenburg, in turn, sent this recipe to Robert Boyle, a promising young experimental scientist who also had a keen interest in alchemical texts.

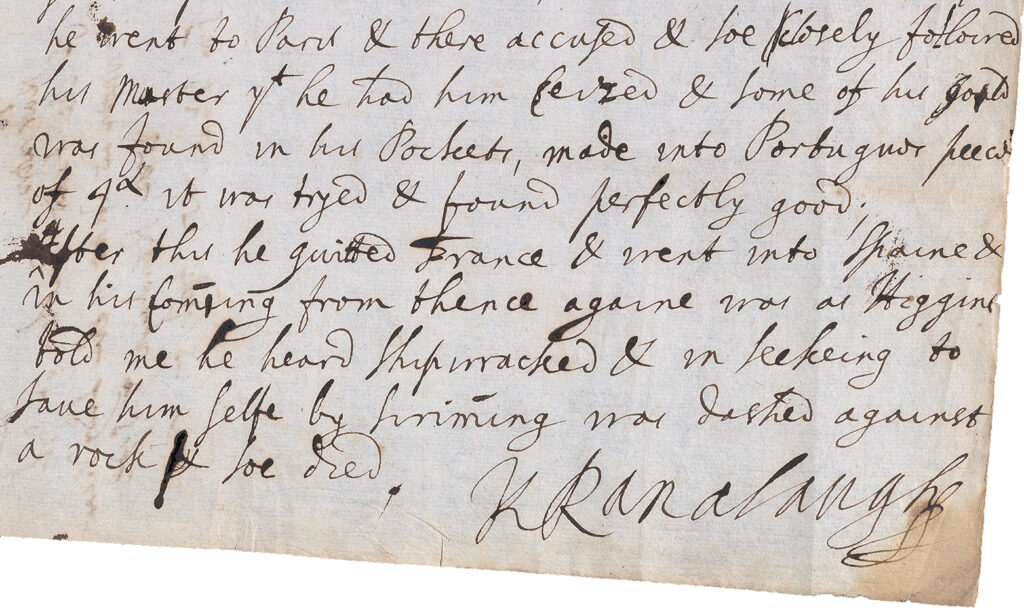

Yet the most detailed description of Butler and his work that survives, and the one that circulated across Europe and as far as New England, was written by Boyle’s sister Katherine, Lady Ranelagh. Widely respected for her insights into science and medicine as well as religion and politics, Lady Ranelagh was a central part of an early scientific correspondence network led by the London-based polymath Samuel Hartlib, who held a prominent role as a disseminator of new scientific knowledge. He employed scribes to copy, edit, and sometimes translate important letters. He then coordinated and circulated their contents to individuals in his network, which included Boyle and Oldenburg.

Butler’s dramatic life story is revealed in a letter Lady Ranelagh wrote to Hartlib in 1659. She explained that her information originated with a well-respected Irish physician named Daniel Higgins, who knew Butler firsthand. Higgins had heard rumors that, as a child, Butler had been kidnapped by pirates and sold to the Pasha of Tunis, known to be a great alchemist himself. At some point, Butler reputedly stole a box of the Pasha’s secret powder and escaped. Curious as to the validity of this extraordinary tale, Higgins enlisted himself into Butler’s service.

The two men worked closely together for some time before traveling to France, where they purchased lead and began a great experiment. Higgins told Lady Ranelagh that they labored together for hours, night after night, to melt and refine the lead, eventually producing a pure and malleable silver. Then, just when the mixture lacked nothing but the secret tincture, Butler sent Higgins on an errand.

Instead of following Butler’s instructions, Higgins snuck outside, hopped on a stool, and spied on Butler through a window. Just as Butler was about to add his famed powder, Higgins tripped and fell off the stool, and the noise caused Butler to stop his work.

Higgins admitted that, close as he was, he never saw the philosophers’ stone in action. Butler, on the other hand, was later arrested for forgery and eventually died in a shipwreck.

This tale may sound ludicrous today, but some of the leading chemists of the Scientific Revolution took it seriously. Hartlib sent a copy of Lady Ranelagh’s story to John Winthrop Jr., the governor of Connecticut a year after she originally composed it.

In his Usefulness of Natural Philosophy, published in 1662, Robert Boyle mentions the “strange testimony” of Higgins and suggests that his readers will believe it if they remember that Higgins was a reputable physician and chemist who had the rare opportunity to live in a shared house with Butler.

In the 17th century, much as today, a person could secure a solid reputation in a number of ways—get a good education; be admitted into professional societies; or produce and share knowledge that can be tested and proven true by others. Such a process is not so different from the way we now discern truth from “fake news”: we look at the source of the information and trust some individuals more than others.

Why did Lady Ranelagh’s strange secondhand account of Butler receive such a far-reaching and long-lived circulation? Well, her esteemed reputation, the genre she used, and trust in the sources themselves played a role. Ranelagh’s letter was written as a witness testimony and includes verifiable names, dates, and locations. Rather than a fanciful work of fiction, it is instead an example of a new way to share evidence with peers. Her brother, Robert Boyle, would spend the next two decades formalizing ways to help readers assess the accounts of witnesses who may not be personally known to them. This approach is a forerunner to today’s peer-review process, in which scientists write an article about their experiments for journal editors, who then select other researchers to review the article, who will, in turn, recommend rejection, acceptance, or changes before publication.

Butler’s story takes place at a time when early scientists were beginning to develop new methods for proving and disproving each other’s claims. While many ancient theories of nature persisted, passed from one generation to the next, these new 17th-century methods allowed individuals to challenge and develop upon past assertions. Today’s accepted theories of matter allow us to dismiss the possible existence of the philosophers’ stone, but throughout the early modern period there were several reasonable explanations that supported its existence.

The speculation surrounding Butler’s claim is a snapshot of early modern experimental science in action. An international group collected evidence, shared their knowledge, attempted to reproduce trials, and thoroughly examined the reputation of the individuals who made these claims. As for those involved in assessing the claim, Oldenburg would soon become the first secretary of the newly established Royal Society, while Boyle would become one of its founding fellows and a leader in shaping the modern scientific method. Oldenburg, in his role as secretary, collated and distributed new scientific claims via the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, the longest-running scientific journal in the world, and published to this day.

Through their search for the philosophers’ stone, Boyle, Lady Ranelagh, and their peers helped create a new way of doing science, one based on the ability to document and reproduce experiments and so discern matters of fact.

For readers who would like to dive deeper into the history of alchemy and the philosophers’ stone, we recommend Lawrence Principe’s The Secrets of Alchemy.