Scientific knowledge often comes from unexpected places. Take the mysterious disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in 2014. On its way from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing, the plane lost contact with air-traffic control and abruptly turned south before running out of fuel and crashing into the Indian Ocean. An international search effort to locate the debris and figure out what caused the deaths of 239 passengers and crew members lasted close to three years and involved helicopter sweeps across the surface of the water, sonar arrays towed by boats, and underwater investigations by submarines and drones. In the end the search covered 100,000 square miles of previously unmapped ocean floor, an area about twice the size of Pennsylvania.

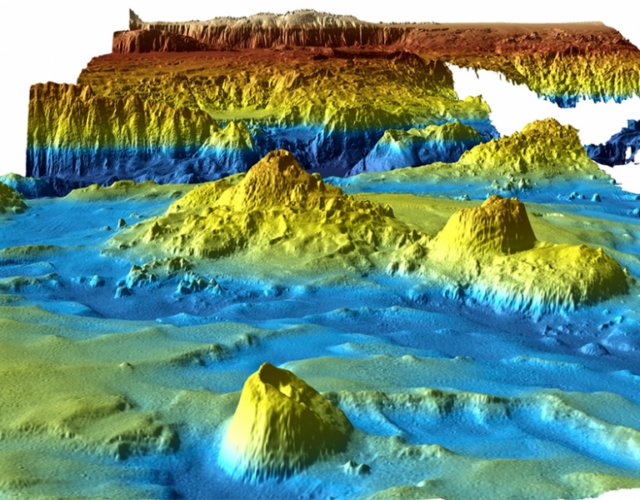

The plane itself was never found. In the years since the crash only a handful of broken pieces have washed up, offering little in the way of closure for the families of those who died. Yet for geophysicists (scientists who analyze the shape and structure of the planet) the crash ultimately provided a trove of new, relatively inexpensive data from the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, which the scientists have used to create three-dimensional maps of underwater volcanoes and mountains with detail down to the centimeter (see the image above). In the future these scientists hope the maps will help them predict ocean currents, tectonic activity, and tsunamis.

Speaking to the New York Times in 2017, geophysicist Millard Coffin was quick to acknowledge that the source of this information was grim. “When we look at these data,” he said, “we’re constantly keeping in mind that we wouldn’t have this data if it weren’t for a terrible tragedy.” But the value of the maps cannot be understated: only 0.05% of the ocean floor has been mapped to the level of detail provided by the search effort for Flight 370. The rest of the ocean has been charted by satellites but only to a resolution of about 5 kilometers in most regions—barely enough to see where the ocean’s largest mountains and ravines are. We know more about the surface of Venus than we do about the ocean floor of our own planet.

Flight 370’s disappearance is not the only disaster that has inadvertently expanded scientific understanding. The 1986 explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant caused the Soviet Union to carve out an “exclusion zone,” an area of about 1,000 square miles surrounding the plant where people are forbidden to live because of radioactive fallout. For more than 30 years the exclusion zone has been essentially uninhabited by humans, and as a result it’s become a nature preserve that has allowed researchers to witness how quickly plants and animals reclaim buildings and roads that aren’t maintained. The most valuable data have come from studying how animals adapt to a highly radioactive environment that is constantly damaging their DNA.

A fence in the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

Since the Chernobyl accident biologists, such as the University of South Carolina professor Timothy Mousseau, have observed animals with hideous tumors, birds with deformed beaks, and a general decline in insect and spider populations. More recently, Mousseau found that some of the surviving animals have developed safeguards against the lingering radiation. A number of bird species now produce higher levels of antioxidants, which protect them from further mutations. In an area called the Red Forest the fallout was so intense that thousands of pine trees died but did not decay; the radiation wiped out most of the microorganisms that normally cause wood to rot, leaving behind a breathtaking forest of reddened trees that appear to be petrified.

But don’t mistake the exclusion zone for some kind of postapocalyptic Eden. Mousseau’s biggest takeaway from studying the aftermath of Chernobyl is that the impact of DNA-melting radiation is nothing compared with the effect of human activity on nature. The plants and animals left alone in the zone are surviving despite the nuclear fallout, but they would be doing much worse if people were still living there. Several species of animals, including deer and wolves, have moved in since the area was abandoned and are doing better than their peers in human-populated regions nearby.

There are countless other disasters that have allowed scientists and researchers to acquire valuable data they would not otherwise have. When a Chilean mine collapsed in 2010 and trapped 33 miners, NASA was able to help keep them alive by realizing the similarities between the cramped conditions of the miners underground and the conditions astronauts encounter in space. And the technology used to get the miners out proved valuable both for planning future space expeditions and for mine safety. Similarly, after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 killed nearly 150 poor New York immigrants, most of them women, researchers studied the unsafe working conditions and lack of escape routes in the building. That research led to updated building safety codes across the entire city that limited the loss of life in later disasters and gave scientists a better understanding of how fire starts and spreads.

It is perhaps perplexing that tragedy is often the precursor to scientific knowledge. But in some ways it makes sense: we learn from our mistakes in order to prevent similar misfortunes in the future. My theory is that such rare events as nuclear meltdowns and collapsing mines give scientists a unique chance to study something they would never be able to simulate without harming people. Scientists tread a fine line between exploiting the victims of disasters and respecting their memory, especially when the science that results from, say, deaths in a plane crash is unrelated to preventing further airborne tragedy. No one wants terrible things to happen, but when they do, it’s comforting to remember that the knowledge gained can help people in the future.