“Everyone hates to see make-up on his wife,” declares the character Lionardo in the Renaissance treatise On the Family (1433), “but no one seems able to prevent it.” Beauty, in early modern Europe, was more than skin-deep. It was a physical reflection of an individual’s health, morality, and state of being. To conceal or enhance one’s true face with cosmetic arts was innately subversive. Yet women did it all the time, breaking rules to conform to expectations.

In a society that openly questioned women’s worth and curtailed their ability to earn a living, women were obliged to rely on their appearance to demonstrate their value and secure an economic future. Were cosmetics an artful aid or a dangerous deceit? The question was at the heart of a centuries-long debate—one that grew ever more complicated as women began to add metallic and mineral ingredients to their makeup. These chemical cosmetics had the power not just to conceal, but to permanently alter the face. Critics denounced them as dangerous. Yet, for some women, the social benefits of looking good outweighed concerns over potentially harmful side effects.

These innovations of chemistry, like so many technological developments since, raised gnarly questions about the cost of progress.

A droll tale by the 14th-century novelist Franco Sacchetti centers on a debate between a group of artisans working at the basilica San Miniato al Monte in Florence. After discussing the virtuosity of the city’s sculptors and painters, the group determines that only the great Giotto himself surpassed the marvelous talents of Florentine women. After all, no others could sculpt themselves new faces using just their makeup brushes. The Latin word arte (skill) encompassed a myriad of technical and artistic abilities, but not women’s talent with makeup. The tale’s humor derived from the unfathomable suggestion that perhaps it should. After all, women put enormous effort and skill into acquiring and applying cosmetics.

In reality, early modern societies often approached women’s artful brushwork with hostility. Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) was a Florentine polymath whose interests touched on a range of subjects, from architecture and painting to civic and family life. His work On the Family is framed as a conversation between Alberti men on household management and the promulgation of the Alberti name. Selecting a wife, Alberti tells us, was of the utmost importance for this purpose. The criteria were “beauty, parentage, and riches.”

Alberti’s emphasis on beauty was based on its profound significance in contemporary natural philosophy. Beauty was deemed a confluence of the rational principles of moderation, symmetry, and proportion, which held that an individual’s spiritual, emotional, and physiological state were interrelated. A pleasing face demonstrated that one’s inner life was well ordered, and it connoted health, fertility, and a virtuous character. Conversely, an internal disorder, brought on by an immoderate lifestyle or unregulated emotions, manifested in a poor complexion. Green sickness, characterized by lethargy and a pallid face, was typically seen in unmarried women who indulged in a lustful pining over forbidden or unrequited love. Thus, women used cosmetics to appear healthy and mask any insinuation of sickliness or sin.

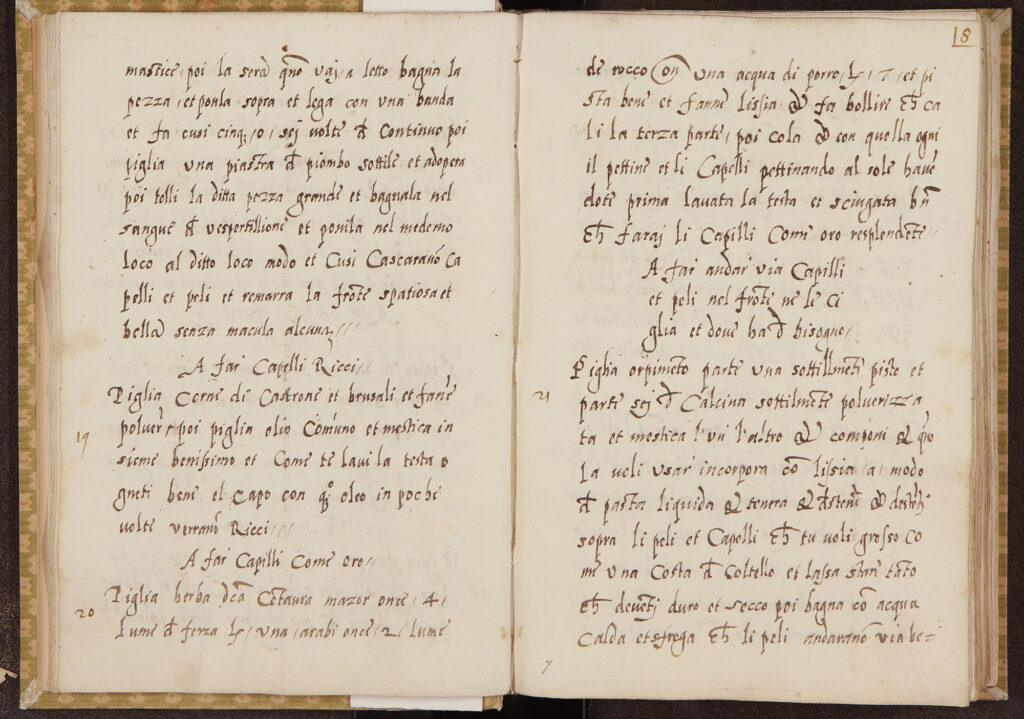

Much about early modern women’s cosmetic practices can be gleaned from household books of recipes. These manuscripts contained a wealth of information, often recording the idiosyncratic needs of their authors. Such is the case with one of the most famous compilations, Gli Experimenti, authored by the dauntless Countess of Forlì and Lady of Imola, Caterina Sforza (1463–1509).

Niccolò Machiavelli captures something of Caterina’s iconoclastic spirit in an apocryphal story from his Discourses in which Caterina abandons her children to enemy forces in wartime to retake the castle in Forlì. “She was no sooner in the castle,” purports Machiavelli, than she “upbraided” the enemy, candidly disabusing her foes of the notion that her children were useful hostages. Lifting her skirts, she “shew’d them her genitals through the windows, to let them know . . . she had wherewithal to have more.” Though the veracity of Machiavelli’s tale is suspect, Caterina’s adventurous life unfolds through her recipes.

Volume B of Gli Experimenti, recently discovered in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, covers human and veterinary medicines, horseshoeing, love charms—all excised to avoid inquisitors’ wrath—and, of course, cosmetics. Caterina’s cosmetics recipes subvert gendered expectations and reflect her understanding of the social economy of women’s beauty and the virtue it connoted. In Gli Experimenti she uses arschemia (the art of chemistry) in recipes designed for and by women, which aided them in appearing to meet the social and physical ideals of their gender. A subversive deception connects her method “to make a woman appear as a virgin even if she is of the age to be corrupted” with a recipe to “lift all wrinkles on the face.” Read alongside each other, the recipes constitute an important body of knowledge developed in response to the immense value placed on virginity, youth, and beauty in a patriarchal society.

Such standards of feminine beauty can be traced to the 14th century and Petrarch’s idealized descriptions of his beloved Laura’s coral lips and locks of gold. By the late 15th century, Italians began using cosmetics to reinforce their whiteness, which became emblematic of European identity following the influx of enslaved people from sub-Saharan Africa into Italian society. Caterina devised bleaches and rinses aimed to make hair “blonde” and “beautiful.” For blush, she used a semipermanent dye made from the pigment of sandalwood soaked in a transparent liquor. White teeth were achieved with an abrasive powder made from ground coral and rock alum. For a “spacious and beautiful” forehead, she supplied a recipe for a sticky substance made of tree resin to be applied over the front of the hairline. She instructed women to let it harden overnight and then wax away the forehead hair in the morning. Forehead waxing may be obsolete, but Caterina’s suggestions for anti-dandruff hair wash and curl-enhancing techniques prefigure today’s beauty practices.

The surest confirmation of cosmetics’ popularity was the vehemence with which their use was decried in public discourse. In On the Family, Alberti disparaged the “powders and poisons which the silly creatures call make-up.” Makeup deceived the viewer, rendering unreliable judgments of who was good and who was not. Made-up women were condemned for undermining the moral order; deception became a sin associated with their sex. The fear of women’s trickery underlies the scene in On the Family in which the character Giannozzo bluntly informs his wife: “You cannot deceive me, anyway, because I see you at all hours and know very well how you look without make-up.”

Such critiques of cosmetics created a precarious double standard that demanded women be both beautiful and natural. If a woman used cosmetics to obtain beauty, she risked being seen as vain, deceitful, and even provocative. Women whose makeup was overdone were frequently compared to prostitutes. However, if she eschewed makeup entirely, she could fall short of the standard that afforded her particular privileges in a society that placed inordinate value on women’s external appearance. To be anything less than beautiful implicitly risked her reputation and prospects for attracting a husband.

The solution to this dilemma was sprezzatura, or the “art of artlessness,” a concept coined by Baldassare Castiglione in his guide to courtly living, the Book of the Courtier (1528). His character Madonna Costanza Fregoso extolls the superiority of this early-modern antecedent to the “no-makeup makeup” look. “How much more graceful a woman is,” she exclaims, “who paints herself so sparingly and so little that whoever looks at her is unsure whether she is made-up or not.”

While sprezzatura remained the preeminent ideal, the ravages of the smallpox epidemics softened public opinion toward cosmetics in the 16th century. Whereas heavy-handed cosmetics were previously associated with prostitutes, now even noblewomen were obliged to plaster their faces to hide disfiguring smallpox scars. The most famous example was Queen Elizabeth I, who adopted her iconic lead-white mask of face paint after surviving a bout with the disease. In this context, cosmetics could be justified on the grounds that rather than creating beauty they merely restored natural beauty that had been lost. In this spirit, the Venetian physician Giovanni Marinello reverses traditional thinking in The Ornaments of Women (1574), maintaining that inner beauty, more important than an unadorned appearance, should be allowed to shine through. Cosmetics were merely aids that helped it do so. With makeup, a woman could accurately signal the virtue of the lady within. Or as Marinello puts it, horses are beautiful but useless unless tamed. By this, he implied that natural beauty required skill to perfect. Mixing his equine metaphors, he concludes that “virtue in a gross body is buried in manure.”

Nevertheless, many authors of cosmetic treatises maintained the superiority of a natural appearance. Paradoxically, they still promoted use of beauty products—just ones that altered instead of covered the skin. In On the Beauty of Women (1548), the literary monk Agnolo Firenzuola draws a distinction between treatments that remove imperfections from the face and makeups that plaster over problem areas. “Waters and powders were in those days invented to remove pimples and moles,” he explains, lamenting how “to-day they are used to paint and whiten the whole face.”

With plastering suspect, the door was open to innovating alternatives ushered in by the rise in alchemical experimentation at 16th-century European courts. Powerful new beauty products promised miraculous, natural-looking results by removing unsightly spots and scars with greater efficacy than ever before. Methods to remove flaws permanently had always existed, but as cosmetics historian Catherine Lanoë’s work has revealed, the new metal and mineral ingredients had an unprecedented power to change a person’s appearance—and cause harm. A manuscript on beauty products originating from the Medici court in Florence offers a recipe for “Virgin’s Milk,” a face-whitening product. It called for fine silver, 24-carat gold, and cautioned: “do not breathe.” Another potent cream, entitled “Beautiful Whitening with silver and copper,” incorporated mercury and arsenic crystals.

For many, chemical cosmetics’ ability to physically alter instead of conceal the face introduced a new thread of moral panic into public discourse on the nature of beauty and artifice. No longer were women silly artists; now their beauty routines were scientific experiments that might easily go awry with ugly consequences. Firenzuola warns his audience of the corrosive effects of chemical cosmetics. His character Mona Lampiada describes another woman, Mona Bettola, who “is like a gold ducat that hath lain in acqua-fortis,” a caustic alcohol made from saltpeter. What’s more, in the eyes of many commenters, these inventions challenged the preeminence of nature and God, who gave women their natural complexions. Their diatribes against cosmetics decried a new danger: not only were these women deceitful and vain; these sins could lead them to irrevocably destroy God’s gifts. For some, it was poetic justice that attempts to fake beauty would cause ugliness. As Firenzuola jeers poor Mona Bettola, “the more she dresses up the older she seems.”

Trial-and-error experimentation with these new ingredients in the 16th century taught women how to avoid such pitfalls. A century later, cosmetic texts circulated this knowledge. Thomas Jeamson’s Artificial Embellishments (1665) advises women “to avoid those things which rather adulterate then adorne the skin, such as Spanish white [typically referring to bismuth] and Mercury,” since these ingredients would cause a “wrinkle-furrowed visage, stinking breath, loose and rotten teeth.” The use of makeup may have been driven by the gendered politics of self-representation and economic opportunity, but it also presented an exciting avenue of intellectual and technical experimentation for women. There would have been no occasion to mock the basis of cosmetic arts, deride women as misguided cosmetic alchemists, or reproduce their collective work had there been no knowledge of their expertise in the field.

Women procured their ingredients from their local apothecaries, gardens, and pantries and generally conducted their experiments at home. As a result, cosmetology has long been overlooked as an area of technical expertise and scientific inquiry in the early modern world. But it’s become increasingly clear that cosmetics were a domestic contender to the public realm of artistic and alchemical virtuosity displayed by male practitioners. Alberti has left us with an insight about women’s agency in this regard. When it came to cosmetics, he complained, women largely did as they pleased, since “no one seems able to prevent it.”