The first step in wisdom is to know the things themselves.

—Carl Linnaeus

From his castle overlooking Prague, Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II threw himself into a mystical quest so consuming that whispers of possession swirled through his court. The portly ruler of Central Europe was gripped by a singular obsession: to uncover the true secrets of the universe and know the contents of the planet and the skies above it and understand the invisible laws that bound it all together.

So Rudolf collected.

More than a simple hobby, collecting was a means to understand and exert control on a world that by the late 16th century had been upended. “Certitudes were breaking down—religious ones and scientific ones, assumptions that had been made by Aristotle,” says Robert J. W. Evans, a historian at the University of Oxford.

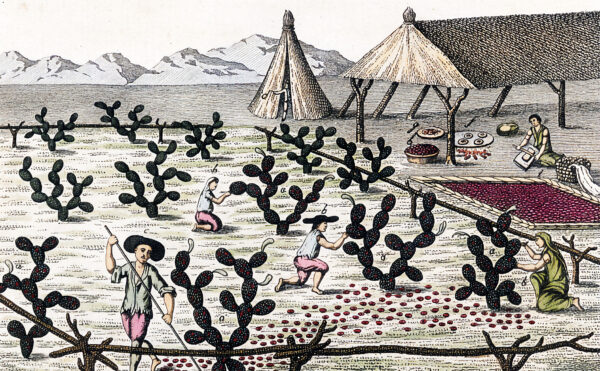

The New World, unmentioned by the Bible or ancient Greeks, seemed boundless, with yet more lands and peoples discovered every few years. New religious beliefs took root across Europe as Protestants broke from the Catholic Church. Radical ideas kept blasting through, among them Copernicus’s controversial theory that Earth wasn’t the center of the cosmos, as had long been believed, but instead revolved around the sun.

Collecting was reconnaissance, a way to decipher a planet turned mysterious. “There was a code to be cracked,” says Evans, “and collecting was seen as part of the way to do it.”

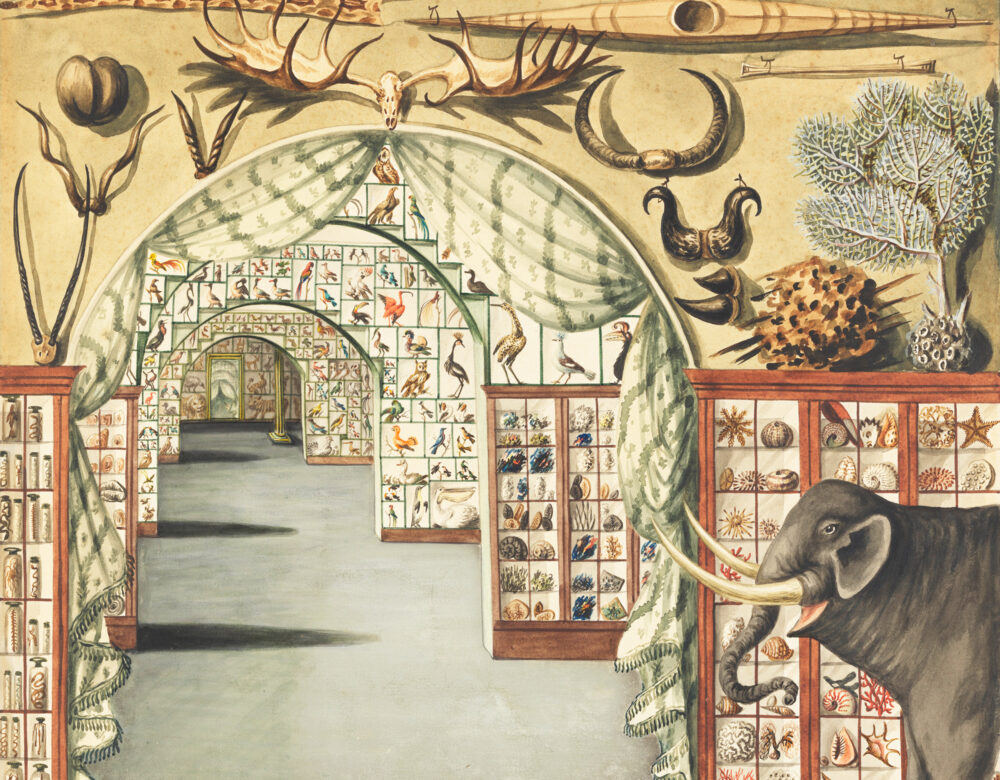

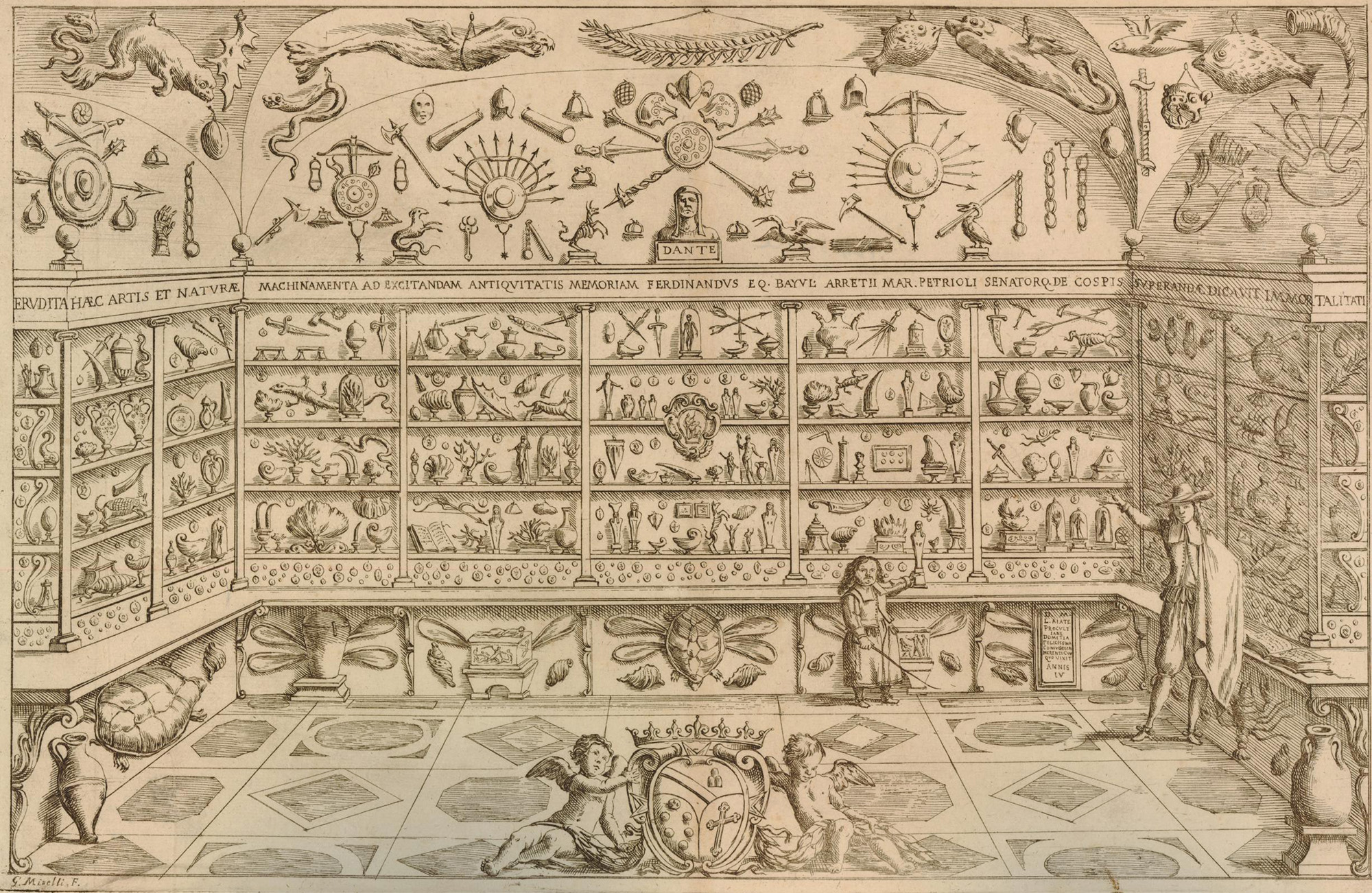

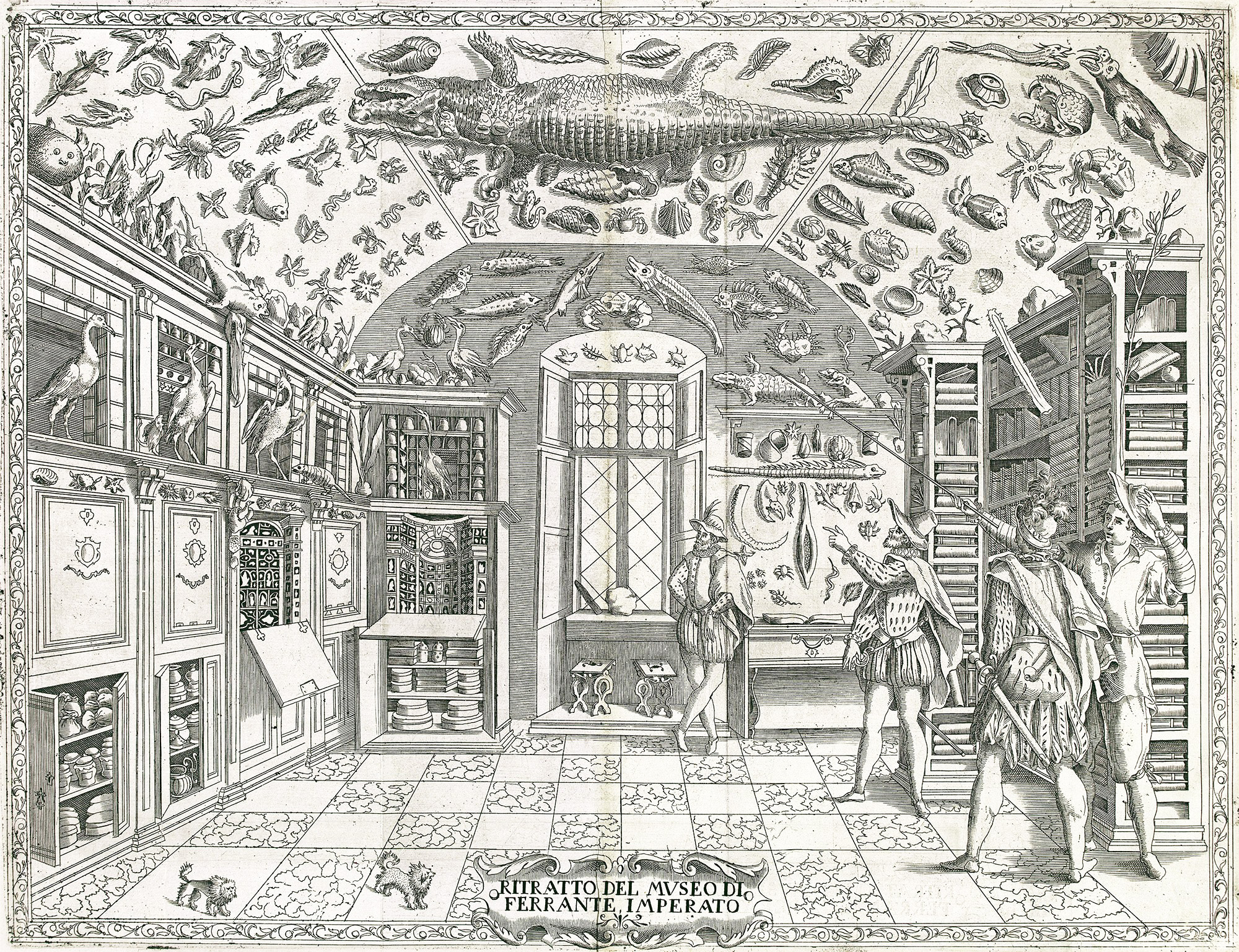

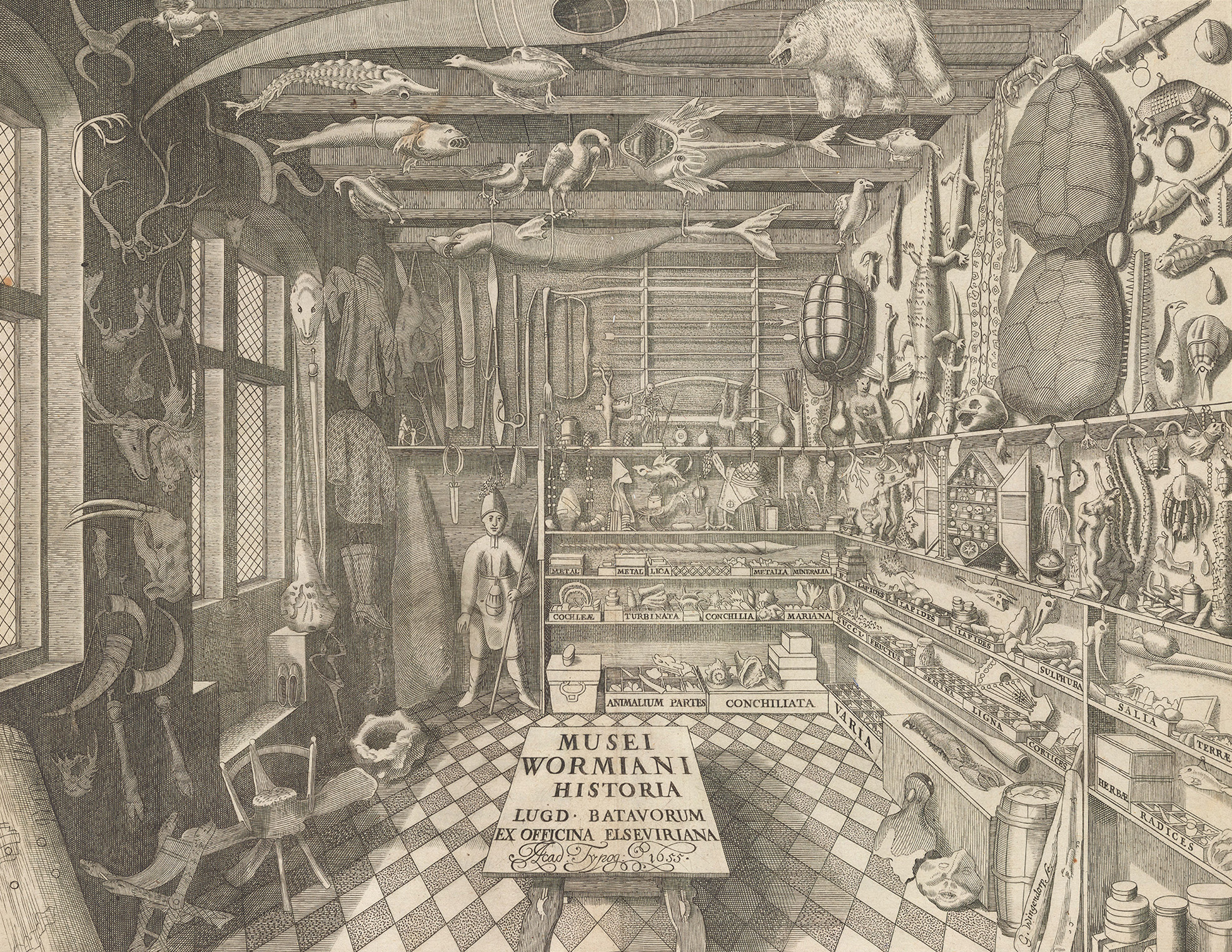

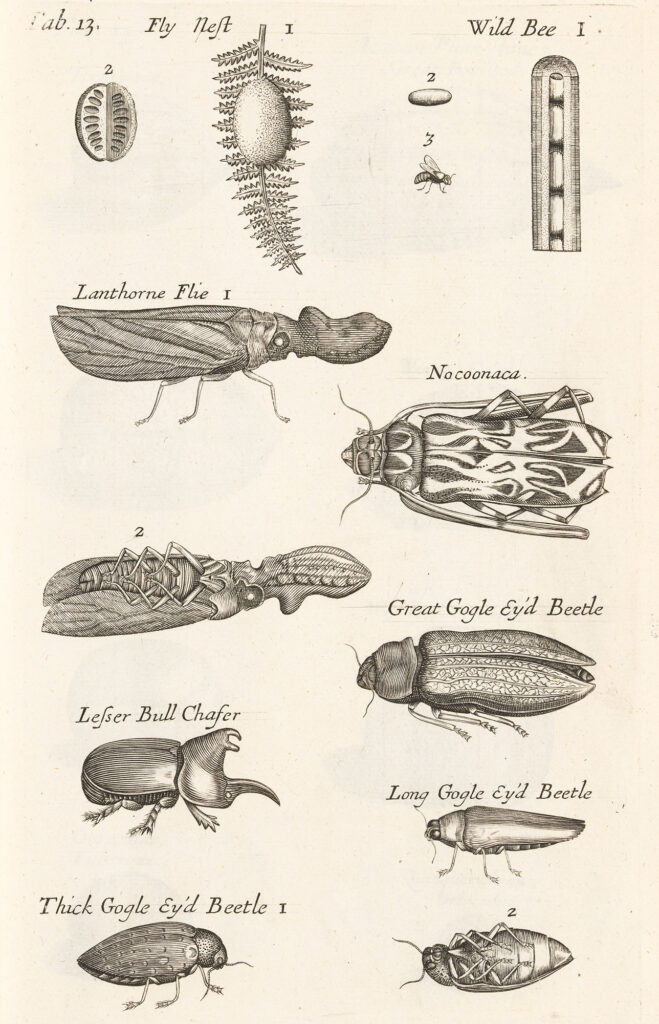

Rudolf wasn’t alone in the pursuit. Nobles, intellectuals, and other elites across Europe joined the craze, acquiring novelties from distant shores—hummingbirds, headdresses of feather, armadillos, scrolls covered in strange scripts—and transforming parts of their homes into showcases.

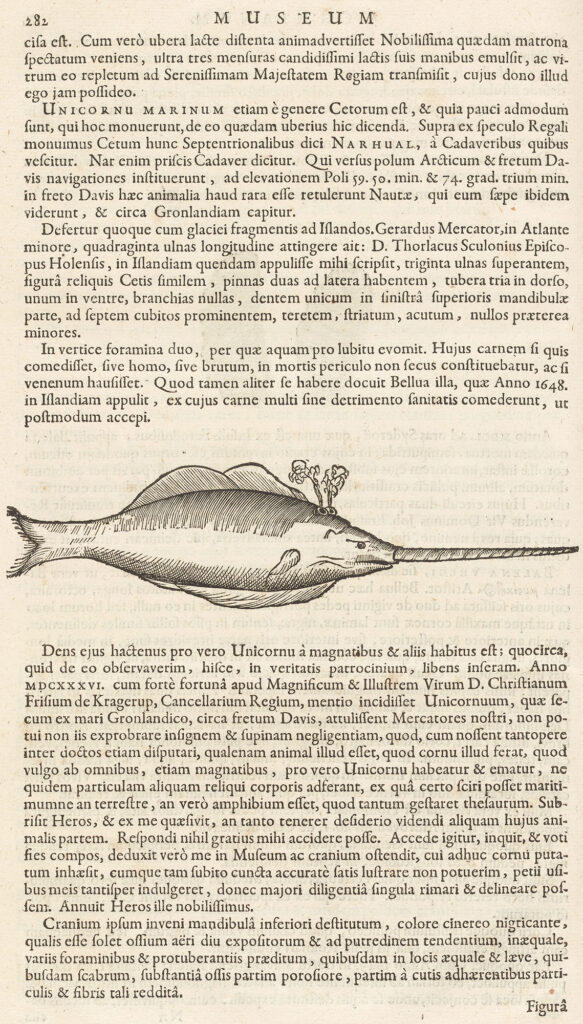

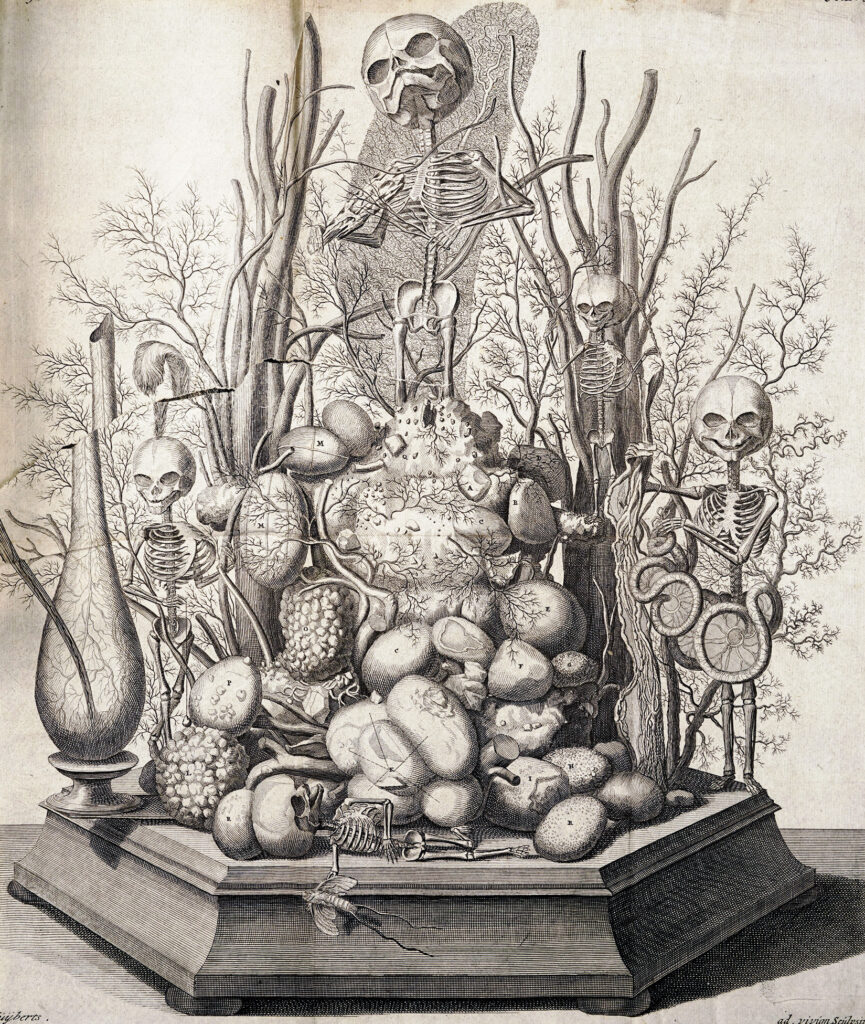

Called cabinets of curiosities (cabinet then meaning private room or study) or Wunderkammern (chambers of wonder), these exotic caches became a veritable fad among royals and scholars of the Late Renaissance. They fired imaginations and fueled competition, while bestowing status on their owners through the wealth and vast knowledge their possession implied.

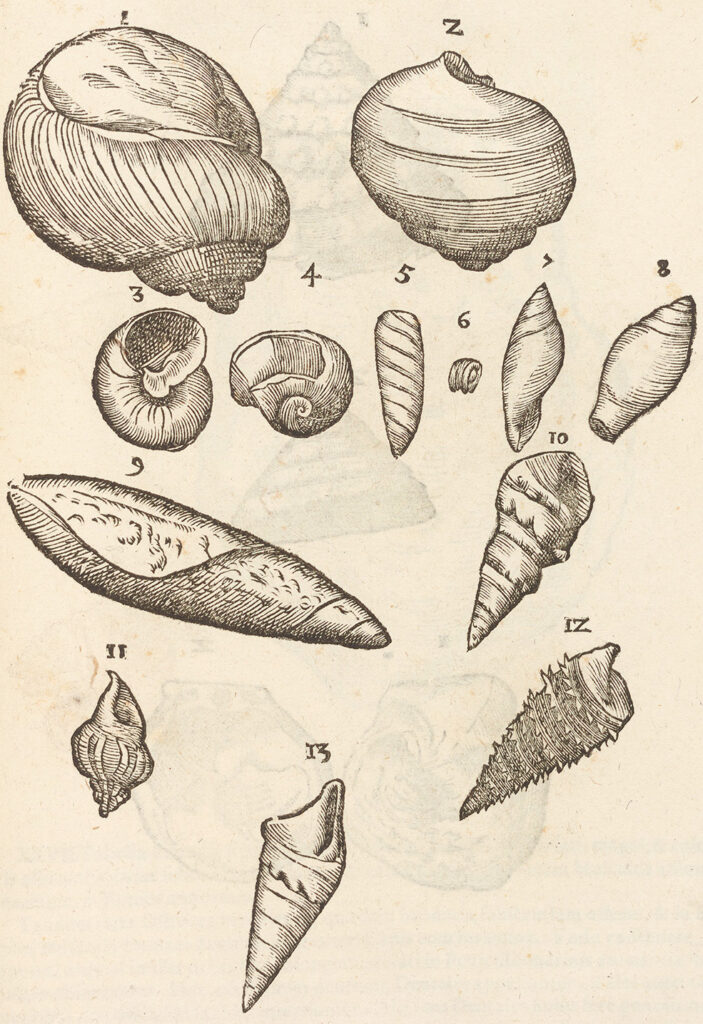

But what in some cases began as princely vanity projects and exercises in one-upmanship also fostered empirical study of the items displayed, furthering understanding of flora, fauna, minerals, even physical laws. And as they evolved, cabinets of curiosities helped lay the foundations of science, bringing together natural philosophers and shaping the questions they asked.