Rebellious, confident, and wildly popular, Olive Thomas was the prototypical Jazz Age flapper, a star of Broadway’s Ziegfeld Follies and many Hollywood films. Thomas married actor Jack Pickford (brother of famous actress Mary Pickford) in secret in 1916. Their relationship was passionate, but it was reckless and strained by the constant travel demands of their careers. In August 1920 the couple sailed to Paris in hopes of salvaging their marriage. What happened on a September night in a suite at the Hotel Ritz would spark a Hollywood scandal.

Jack Pickford had been using a powerful poison, mercury bichloride, to treat a syphilis infection; he would rub a solution of the medicine on his skin before going to bed. After one drunken night on the town Thomas had trouble sleeping. According to her husband she went to the bathroom and swallowed a lethal dose of Pickford’s medicine. Whether it was a mistake made in the dark or an attempt at suicide was never determined. Thomas was rushed to the hospital, but it was too late. She died five days later. Police ruled Thomas’s death an accident, but rumors of murder lingered and controversy dogged Pickford.

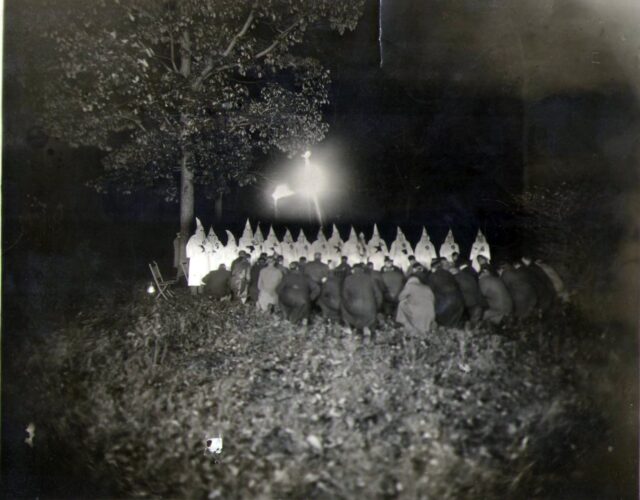

Thomas’s poisoning by mercury bichloride wasn’t particularly odd. Newspaper articles during this time often reported suicides and accidental deaths from mercury bichloride; a headline from the July 29, 1913, San Francisco Call reads, “Girl Makes Great Mistake—Bichloride Is Not Candy.” But one case of mercury bichloride poisoning from 1925 appeared on the front page of nearly every newspaper in the country. That poisoning unearthed the vicious crimes of one of the most influential men in Indiana and destroyed the state’s most powerful political organization at the time, the Ku Klux Klan.

Newspaper articles reported numerous suicides and accidental deaths from mercury bichloride; a headline from the July 29, 1913, San Francisco Call reads, “Girl Makes Great Mistake—Bichloride Is Not Candy.”

David Curtis Stephenson, a portly 30-something with a round, plump face, joined the Indiana Ku Klux Klan in the early 1920s. In contrast to his unremarkable appearance Stephenson was witty and persuasive. No one knew where he came from, but rumors of his checkered past were brushed aside once he used his charm to recruit more than 250,000 new Klan members in just two years. Stephenson’s success rocketed him to the top of the Indiana Klan hierarchy. In 1923 he became Grand Dragon.

Stephenson forged the state’s Klan into a powerful political fundraiser and reliable voting bloc, one with the size and discipline to dictate who got elected to state offices and how those men voted once they were installed. Through this arrangement Stephenson could influence most bills that passed through the state legislature. He handpicked the mayor of Indianapolis as well as the governor of Indiana, Ed Jackson. It was at Jackson’s inaugural banquet that Stephenson first met Madge Augustine Oberholtzer.

Oberholtzer, an attractive 28-year-old Indianapolis educator, attended the banquet with the event’s planner, Stanley Hill. The two were dating, but that didn’t stop Stephenson from asking Oberholtzer to dance. As they swayed to the music, Stephenson may have bragged that he single-handedly got Jackson elected. He might have also revealed his aspirations for becoming a senator and eventually president of the United States. Oberholtzer was impressed.

She began seeing Stephenson during the months that followed, and Stephenson used his political influence and wealth to woo Oberholtzer, including saving her job from state budget cuts. Stephenson’s wealth gave him a taste for bluster and lavish clothing. He was often seen wearing the brightly colored robes of the Klan leadership while entertaining politicians on his yacht. He bragged about his supposed friendship with the president of the United States and even installed a fake phone in his office that he claimed was connected to the White House.

But Oberholtzer came to see past Stephenson’s bravado and vanity and gradually drifted away from him. She may have heard rumors of his mysterious past: an abandoned child and abused wife. Despite his efforts to pull her in, Stephenson realized he was losing her interest.

On the night of March 15, 1925, Oberholtzer came home to find a message from Stephenson. When she returned his call, a drunk, desperate-sounding Stephenson begged her to come over; he had something very important to tell her. Oberholtzer knew how Stephenson changed when he drank. Feeling uncertain, she was escorted to his mansion by one of Stephenson’s cronies.

When she arrived, Stephenson proclaimed his love and asked her to go with him to Chicago that night. When Oberholtzer refused, Stephenson forced her to drink until she was ill and then drove her to the train station with two of his bodyguards. Inside a private room on the train Stephenson raped and brutalized Oberholtzer. When she tried to fight back, he brandished a gun.

Stephenson’s drunken rages were not unfamiliar to his fellow Klansmen. In 1924 an actress accused him of locking her in a room at a party where he tried to bite and rape her. A manicurist accused him of attempted rape after she refused an offer of $100 to sleep with him. Stephenson frequently held drunken orgies in his home where he assaulted young women. But none of these complaints were ever seriously pursued by authorities.

Stephenson left the train the next morning in Hammond, Indiana, and checked the group into a hotel. A battered Oberholtzer begged to send a letter to her parents; Stephenson relented when she agreed that he could write it. Later that day he allowed her to make a chaperoned trip to a drugstore to buy makeup to cover up her wounds.

But Oberholtzer wasn’t after makeup; she wanted a bottle of mercury bichloride tablets, which she bought and hid under her coat. Once back at the hotel she swallowed six tablets. Within minutes she was vomiting blood.

Mercury bichloride (HgCl2) is highly toxic; just three tablets are enough to kill an adult, and in the early 20th century almost anyone could buy it at a pharmacy without a prescription.

The earliest written account of mercury bichloride comes from Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi, known in the West as Rhazes, a medieval Persian physician, chemist, and philosopher. During the 10th century Rhazes developed a water-soluble version of mercury that was used to clean wounds.

Metallic mercury will mostly pass through the body without doing major damage, says historian of medicine Diane Wendt. Mercury bichloride, in contrast, is absorbed into the bloodstream and organs where it damages kidneys and the intestinal tract, causes internal bleeding, and, at a high enough dose, kills. As recently as the early 1900s it was used to treat syphilis. (Jack Pickford, Olive Thomas’s husband, died at the age of 36. Although his mercury bichloride treatments for syphilis were not blamed at the time, they may have contributed to his early death from multiple neuritis, a nerve condition that sometimes results from diabetes, consumption of alcohol, or exposure to toxic metals, such as mercury.)

Oberholtzer admitted to poisoning herself when Stephenson found her covered in blood and vomit. She pleaded for him to take her to a hospital. Stephenson agreed on one condition: that she pretend to be his wife. Oberholtzer refused; so Stephenson and his cronies dragged her to a car and drove her back to Indianapolis. During the ride she begged them to leave her on the side of the road or take her to a doctor. Stephenson ignored her pleas and promised that he would marry her. When she appeared near death, they carried her back to her home and left her to die, claiming that she was injured in a car crash.

Stephenson probably wasn’t too worried about the police. In 1923 he had separated the Indiana Klan, one of the most powerful Klan branches in the country, from the national organization. The move bolstered Stephenson’s power by giving him control of most political offices in the state. (Many politicians, judges, and police officers regularly accepted bribes from the Klan.)

Stephenson forged the state’s Klan into a powerful political fundraiser and reliable voting bloc, one with the size and discipline to dictate who got elected to state offices and how those men voted once they were installed.

But Stephenson could not predict that Oberholtzer would revive long enough to give a lucid, detailed testimony of the assault. Nor could he predict that his network of political connections would abandon him. The jury in the trial Stephenson v. State sentenced Stephenson to life in prison for second-degree murder.

Stephenson still wasn’t worried. He was the most powerful man in the state, and he had helped elect Jackson as governor. The inaugural ball where he met Oberholtzer was as much a celebration for him and the Klan as it was a celebration for Jackson. He was confident Jackson would offer him a pardon and that he would dodge the consequences of his crimes as he always had. Except this time he didn’t. Jackson ignored Stephenson’s pleas for help.

Scorned by his political network, Stephenson grew vindictive. He sent the name of every politician who had accepted a bribe from the Klan to the Indianapolis Times, starting with Jackson. As national newspapers exposed the web of the Indiana Klan’s influence, the Klan’s image as a champion of morality and patriotism was destroyed. The Indiana Klan dissolved within a few years.

Perceptions of mercury bichloride changed too. The publicity surrounding Stephenson’s case galvanized efforts to regulate the drug and led to restrictions on access to it. Changes to how mercury bichloride was distributed and marketed had been under way for decades, says Wendt. One of the first innovations, proposed in the American Journal of Pharmacy in 1914, was to change the shape of the mold used to make the tablets. People, especially children, found it easy to mistake the tablets for less dangerous medicines and even candy. In response many companies switched to blue pills that looked like tiny coffins. Congress later passed regulations that required the word poison to be prominently displayed on each bottle and imprinted on each tablet.

Stephenson was released from prison in 1950 but violated his parole and was sent back. A new governor pardoned him six years later. In 1962 police arrested Stephenson for the attempted rape of a 16-year-old girl. He was released after being slapped with a $300 fine. He died in 1966 at the age of 74, a year after marrying a woman who knew nothing of his past.

The bottle of mercury bichloride in CHF’s collection did not contain the tablets that killed Oberholtzer, but it was manufactured in Indianapolis, the city Stephenson ruled and where Oberholtzer died. Oberholtzer may well have swallowed tablets from an identical bottle manufactured by the same company: death in the shape of tiny blue coffins.