The Manhattan Project, an enterprise of massive scale and unyielding deadline, repesented a new kind of science. Its goal of designing and creating the first atomic bombs in secret enveloped three primary U.S. geographical sites and the lives of some 130,000 scientists, administrators, service workers, and laborers during a period of 30 months. The largest site, built around Hanford, Washington, was responsible for manufacturing plutonium. DuPont was called on to construct and run the engineering works on the strength of its expertise in scaling up. With the imperative of finishing the project DuPont would need to make unprecedented demands on an uprooted workforce of 50,000. In turn, the company made extraordinary concessions to its workers’ physical and social needs. But first, there was some building to do.

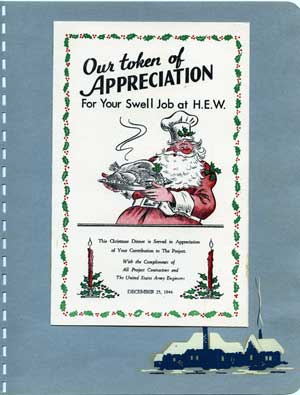

Santa Claus made sure not to overlook Hanford’s hopeful children.

In winter 1942 construction began at the remote semidesert region chosen for the Hanford site. The first of the workers laid roads and electrical, telephone, and sewer lines, as well as the foundations for utilities that would support the workers of the next wave. These workers built facilities for lodging, hospitals, and all of the necessities of daily life that would in turn support the construction of the reactors and the Hanford Engineering Works proper. The workers put in 10-hour days and, having been drawn far from their homes during the wartime labor shortage, were installed in spartan lodging. Attrition in the camp averaged hundreds of workers per day during the life of the project, but progress could not let up; here, time was more than money. From the beginning the planning of the site took the needs of a displaced workforce into account, but the Christmas holidays of 1943 and 1944 merited special treatment. The project’s propaganda messages, conveyed in billboards, flyers, and its Sage Sentinel newspaper, had long urged that workers purchase war bonds—to “S-T-A till it’s done,” and think of safety first. Now the Manhattan Project cordially invited its workers to a myriad of holiday celebrations.

The “Yuletide Carnivals” were thrown by DuPont to stabilize morale and keep turnover in check during a crucial point in the project. For all of the cheer and comfort that was projected, planning the activities and performances was a complex bureaucratic affair: the cache of photographs and documents represented on these pages includes an organizational chart that delegated each aspect of the holiday social planning as well as detailed reporting on event attendance levels. Each carnival was a carefully planned series of events that began in the middle of December and culminated in parties on New Year’s Eve. All workers were invited to complimentary Christmas Day dinners; most of the holiday schedule, however, noted separate activities for “white” and “colored” workers. The latter group was normally treated to simple diversions, such as games of cards and bingo, but the former group attended somewhat more extravagant functions: variety shows featuring well-known bands and singers, boxing and wrestling matches, circus acts, dances, a visit from Santa. Religious as well as secular symbols dotted the camp: handmade nativity scenes posed for DuPont’s photographer, as did Santa and his reindeer-drawn sleigh.

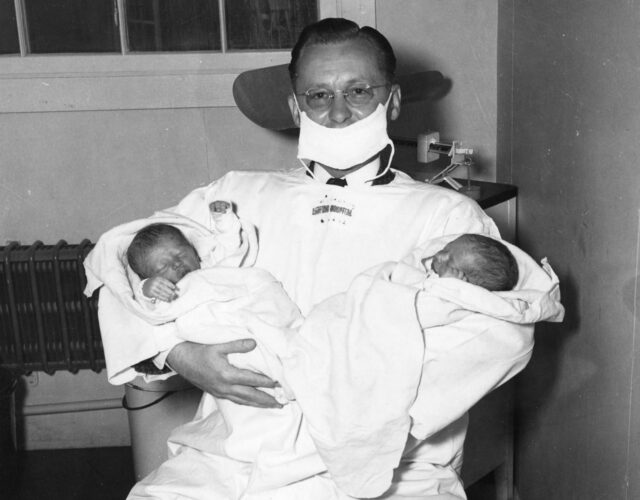

The holiday celebrations may have averted a morale disaster, but consideration of the day-to-day physical and social needs of workers at the camp was equally important to the mission of keeping a stable workforce at Hanford. The commissary saw to cleaning up living quarters and serving scaled-up meals in mess halls placed all around the camp. Pay wagons visited workers in the field to distribute wages. Homes were built in the nearby town of Richland to house families; race- and sex-segregated barracks lodged workers who were single or came to Hanford without their families. Hospitals cared for the sick and the expectant alike. The planned town of Hanford included a library, movie theater, churches, a post office, grocery stores, barber shops and beauty parlors, pool halls, beer taverns, a bowling alley, baseball diamonds, and even a jewelry shop, all designed by the Manhattan Engineering District. Life, even the expansion of families, had to go on as usual, or as near to it as possible. Workers had to appreciate the convenience and comfort of their setting, yet not appreciate that they were confined to a watchfully secured zone. Author Peter Bacon Hales described Manhattan Project camps as “somewhere between an army base and a utopian social experiment.” In due time shipments of plutonium, the precious matériel whose production the workers unwittingly aided, were received at Los Alamos.

This article was developed with the suggestions and assistance of Benjamin Blake, former archivist, and Jon Williams, curator of prints and photographs at the Hagley Museum and Library. Photographs taken by Hanford Engineering Works. Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library.