It’s the kind of thing you’d remember, making an outrageous bid while cruising home in a flying observatory with an astronaut for a bridge partner.

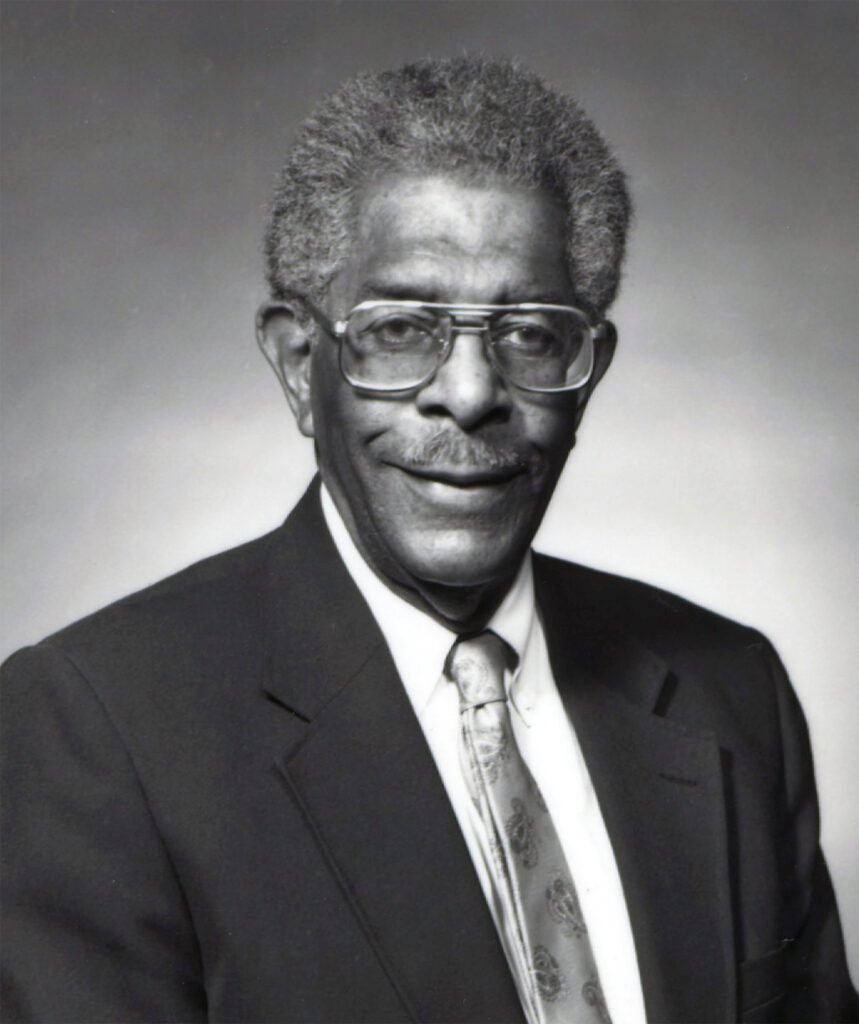

Charles E. Anderson was telling the stories of his life. An old buddy was recording them for the American Meteorological Society’s oral history project. It was the second day of summer in 1992, and they were in Raleigh, on the campus of North Carolina State University, where Anderson had worked until a few years prior.

Anderson had just finished a tale about making rain as a grad student. The U.S. Air Force had given Anderson—along with Ted Fujita and a couple of other meteorological luminaries—use of a C-130 to seed clouds with amines, a class of chemicals produced as ammonia breaks down. The amines turned temperate clouds tropical, in effect, by preventing water droplets from freezing around naturally occurring atmospheric impurities.

“I don’t think the EPA and the environmental people would allow us to do that sort of stuff any longer,” he mused. At age 73, Anderson’s voice was languid and gentle, with a hint of a southern accent.

Anderson had gotten his start in meteorology during World War II while serving as a weather officer for the Tuskegee Airmen. Originally a chemistry student, he went on to complete his dissertation on cloud dynamics (“A Study of the Pulsating Growth of Cumulus Clouds”) in 1960, making him the first African American to receive a PhD in meteorology. His buddy Earl Droessler, who had also served as a meteorologist during the war, asked what happened next.

“I moved to Los Angeles,” Anderson replied. There he formed a group doing atmospheric analysis for the missiles and space division at Douglas Aircraft. “It would put me into the space age and all the hoopla and glamour surrounding that new era.”

Douglas was building rockets for NASA and missiles for the U.S. Air Force. Anderson helped Douglas’s rocket scientists understand the air they were shooting through. He built some of the earliest computer simulations of clouds. He and his team also wrote handbooks that pulled together what was known about Mars and Venus. It seemed a useful thing to do during “the early stages of interplanetary exploration,” Anderson figured. “They got wide publicity. Douglas was very proud.” Anything seemed possible in Los Angeles in 1961.

But the story Anderson was itching to tell started out in the California high desert at China Lake, the Naval Ordnance Testing Station where the U.S. Navy conducted research on ballistic missiles and weather control, among other things. Researchers at China Lake told Anderson about an upcoming eclipse.

“ ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could learn more about the sun if we get above most of the earth’s atmosphere?’ ” the navy guys asked. “ ‘You’re at Douglas, so if we get one of their DC-8’s as a platform. . . .’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll look into it.’ ”

Anderson talked to Wolfgang Klemperer, the chief scientist at Douglas. Klemperer had engineered zeppelins for Goodyear during the 1920s and then designed balloon capsules to carry men into the stratosphere for the National Geographic Society and U.S. Army Air Corps in the 1930s. The old, ever-inquisitive Austrian was intrigued and agreed to come on board as scientific director.

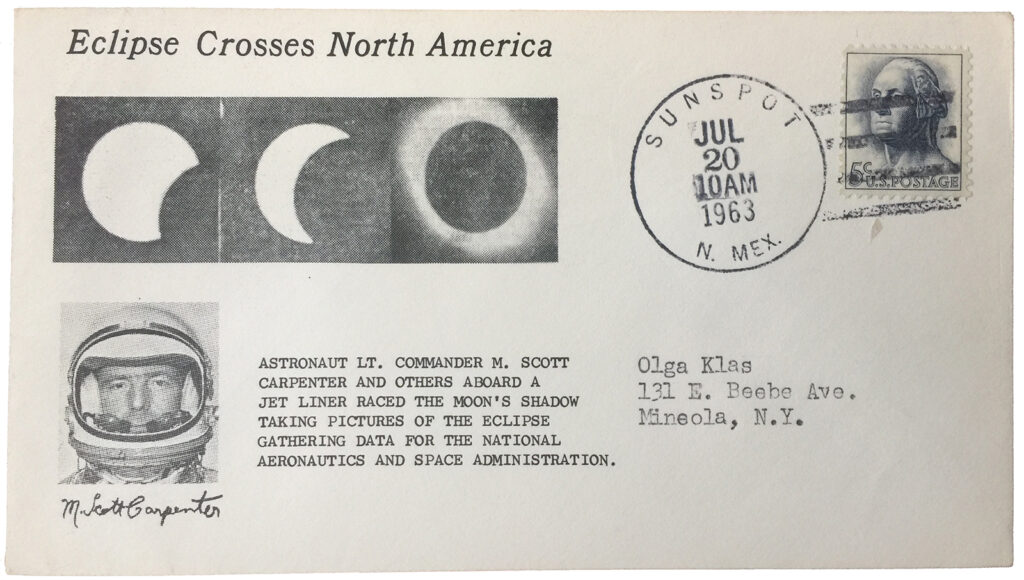

Anderson explained their plan: “Take out all the seats on one side [of a DC-8] and install special windows for those who needed them, and put the instrumentation in the windows, and we’ll fly a course that will parallel that of the sun moving across the earth.” They called the project Aerial Photography of the Eclipse of the Quiet Sun (APEQS), pronouncing the acronym apex.

Douglas leased Delta Airlines 801, a DC-8 that was back at the factory for an engine upgrade. The National Geographic Society got behind the scheme too, along with 11 other research organizations. Anderson was especially impressed when Jules Bergman, a noted science journalist on ABC television, asked to join them. NASA was sending along Scott Carpenter, of Mercury mission fame, and astronomer Jocelyn Gill, who was there to explain to the astronaut the dim-sky phenomena he and his colleagues might encounter in space. Anderson was named expedition meteorologist, one of 55 scientists who would be aboard the specially modified plane.

The eclipse would take place on July 20, 1963.

“We estimated by flying along with the sun we could extend the length of observation time for the eclipse,” compared to being stuck on the ground. “But, more important, we could almost guarantee that one could get observations because we would be above the clouds,” Anderson remembered.

They would catch the moon’s shadow above the Canadian Arctic.

“This is a pinpoint operation—we had to be right in the center of the umbra to do what we wanted to do,” Anderson explained. Those tasks included measuring the sun’s infrared radiation in ranges never before recorded and studying the role of sodium atoms in the ionosphere, that region of the upper atmosphere so important to long-range radio communications. One of the navy guys from China Lake was bringing along an exquisitely sensitive photometer to measure Earth’s airglow, invisible during daylight and thought to be caused by chemical reactions in the ionosphere.

Anderson arrived at the team’s departure point in Edmonton the day before the eclipse. He went straight to the airport’s weather office to discover that the mission might be in jeopardy.

Navigation was already going to be tricky. That part of the world didn’t have LORAN or other radio navigation aids at the time, and the pilots wanted to see a landmark on the ground to confirm the accuracy of their dead reckoning.

“Things didn’t look too good. There was a front coming in from the Pacific and we didn’t know how extensive the undercast would be. . . . I said, ‘My goodness, what are we going to do?’ ”

But eclipses don’t wait for good weather. The scientists pushed on.

“We took off and we flew up over the Great Slave Lake,” Anderson recounted, but the clouds had started to gather below. “We got higher and higher and still more clouds. We finally broke out of the clouds at 41,000 feet.” The cirrus stratus was thick beneath them. “We couldn’t see a ground feature of any kind, nothing.” Their rendezvous with the sun was over an isolated village at the confluence of two rivers, if they could find it.

“I don’t know,” Anderson continued, “but it seems like I have been blessed with good luck.” Just as the plane neared where the pilots reckoned the old outpost might be, a single hole opened down through the clouds. There it was, at the junction of two rivers. “ ‘Ha, we’re at the right spot!’ ” Anderson remembered with delight.

Hitting the right spot meant they spent 142 out of 144 possible seconds in totality, according to National Geographic. “The fellows got marvelous, marvelous observations,” Anderson said.

Out came the champagne.

“We toasted everybody on it, and movies were made. I’ve got a movie over there now that shows the whole thing.” (Perhaps the only existing copy of that movie, Eclipse of the Quiet Sun, can be found in the special collections vault at Cleveland State University.)

On the flight back to Long Beach the scientists swapped the champagne for a deck of cards. Anderson and Carpenter were partnered in a game of bridge. All the space-age hoopla and glamor had made Carpenter one of the most famous men in the United States. Luck seemed to still be on Anderson’s side.

“I drew a hand that had seven diamonds, had all the honors except the queen,” Anderson remembered. “Of course, the cards that were distributed with other people were making strong bids, too. I can remember going to seven diamonds hoping I could get by without the queen—but we went down.”

“Down one?” Droessler asked. “You couldn’t finesse it?”

“Couldn’t finesse for the queen. But I will ever remember that.”