On February 11, 2011, wildlife veterinarian William Fowlds got a call from a ranger at the Kariega Game Reserve in South Africa. As Fowlds recounted in his 2012 online article “Poached!” a rhinoceros had been attacked the previous night, its horn hacked off at the base with a machete. Fowlds told the ranger he would come later that day to analyze the corpse. “William,” the ranger said, “he is still alive!”

Soon Fowlds was barreling down the coastal highway, desperate to get to Kariega in time to help. Half an hour later Fowlds had reached the reserve. He pushed his way through the bushveld until he found the wounded animal. He had seen poached rhinos before, but this scene was more brutal than anticipated. The rhino’s horn was completely gone, as was much of its face. Blood dripped from the gaping hole in the animal’s head, exposing white bone and pink sinew. The rhino hobbled toward him, one leg useless, grinding its mangled snout into the dirt as a crutch to prop itself up.

The poachers had sedated the rhino, taken its horn, and left it to bleed out. But somehow the animal survived the night; now it was awake and in immense pain. Fowlds knew that the rhino was going to die no matter what he did. The only humane action was to put it down. He prepared an overdose of anesthetic, likely the same drugs the poachers had used. As Fowlds plunged a dart into the animal’s rough hide, he wondered what could have motivated someone to carry out such a heinous act.

The answer, of course, is money. Rhino horn can be sold for $60,000 per kilogram, making it more valuable by weight than gold, cocaine, or ivory. Before the 1970s the greatest threat to rhinos came from trophy hunters and the use of horn in traditional Chinese medicine. International trading in rhino horn was made illegal in 1977, but a few years later an appetite for daggers with ornately carved horn handles in Yemen made demand spike and drove rhinos to the brink of extinction. Since the 1990s, rhino populations have started to bounce back, but now a new surge in demand is driving the price of their horn to unprecedented heights.

Rhino horn can fetch $60,000 per kilogram on the black market, making it more valuable by weight than gold, cocaine, or ivory.

Since the 2000s, a growing middle and upper class in Vietnam has sought cutlery and jewelry carved from rhino horn as a status symbol and coveted the horn’s shavings as a cure-all for everything from a hangover to cancer. Vietnamese who want horn today have to import it, generally from South Africa: the last Vietnamese rhino was declared dead in 2011.

Though buying and selling rhino horn is technically illegal in Vietnam, it is easy to find in city markets, as BBC journalist Sue Lloyd-Roberts discovered in Hanoi in 2014. At first she was closely followed by her government chaperone, and no vendors were willing to sell to her. But when she returned to the shops without her minder, traders were “happy to oblige,” she wrote. Roberts claimed that her husband had cancer, and the seller told her that if she ground up the horn and mixed it with alcohol, she would have an 85% to 90% chance of curing him.

Traditional Chinese medicine has affirmed the healing powers of rhino horn for thousands of years. Contemporary rumors of rhino horn’s cancer-fighting attributes started in the mid-2000s, when a Vietnamese politician was said to have survived cancer by treating himself with the shavings.

But you’d have the same chance of curing cancer from chewing your fingernails. Like our nails and hair, rhino horn consists mostly of keratin.

In 2011 the president of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine announced that “rhino horn is no longer approved for use by the TCM profession and there is no traditional use, nor any evidence for the effectiveness of, rhino horn as a cure for cancer.” But that repudiation has done little to convince consumers or practitioners, and it hasn’t stopped poachers from killing more than 6,000 African rhinos since 2008 to satisfy continued demand.

It may not be long before the rhino-horn market kills itself.

Given there are fewer than 30,000 rhinos left in the wild today (down from 500,000 in 1900), it may not be long before the rhino-horn market kills itself. The conservation group Save the Rhino estimates that if poaching continues to grow at its current rate, the rhino could be extinct in the wild within the next 10 years.

To avert that fate conservation groups have deployed a number of tactics. Their first lines of defense are the borders around national parks. Dozens of African wildlife reserves have become war zones, with park rangers and poachers caught in an arms race in which each tries to stay ahead of the other with long-range rifles, hunting dogs, helicopters, and night-vision goggles. Kariega and other reserves are chronically understaffed and are under constant threat from those hired and armed by international crime syndicates and terrorist organizations, such as Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab, that use poaching as a source of income. As soon as rangers arrest one group of poachers, another group pops up on the other side of the park.

Officials have tried a variety of conservation efforts with mixed success. Top left, Antipoaching forces stage a mock capture and arrest of poachers on a South African game farm in 2010. Top right, A drugged black rhinoceros in South Africa’s Ithala Game Reserve being moved to a safer location by helicopter. Bottom, An orphaned baby white rhinoceros being fed at Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, Kenya.

While rangers struggle to protect rhinos in their habitat, conservationists have opened a new front in the battle against poaching, targeting consumers. In 2013 the World Wildlife Fund partnered with TRAFFIC, which monitors trade in wildlife and animal parts, to run advertisements in Vietnam meant to curtail the market for horn. One poster shows a rhino standing in tall grass with a human foot in place of its horn. The caption reads, “Rhino horn is made of the same stuff as human nails. Still want some?”

The resounding answer is yes. Demand for rhino horn in Vietnam has barely dipped since the advertising campaign began.

Some conservationists have experimented with more devious types of deterrence: they trim, dye, and even poison the horns of living rhinos. That way if poachers capture a rhino, there won’t be any horn to harvest, or they won’t be able to sell it if it’s a strange color or it will make their clients sick. Still, these measures require that each year rangers track down, drug, and operate on every rhino in their reserve, a practice that can be dangerous for both rhinos and rangers. On top of that, even carefully removing or altering a rhino’s horn could affect the animal’s ability to forage for food, defend itself, and find a mate. These techniques could hurt more rhinos than they would help.

Ultimately, the problem conservationists face is an economic one: the scarcer the resource, the more valuable it is and the further traffickers will go to exploit it.

Are conservationists too stubborn to accept an outsider’s approach?

In response to this crisis a Seattle-based biotechnology start-up is attacking that market in a new, controversial way. Pembient (the name comes from the word pembe, Swahili for horn) wants to mass-produce lab-grown rhino horns that are molecularly identical to the real thing, then flood the market until the price of real horn crashes and poaching is no longer economically worth the risk. Rather than force people to choose between their faith in Chinese medicine and the survival of an entire species, Pembient wants to satisfy demand for horn without having to ever harm another animal.

The scheme has raised concern among conservationists who believe flooding Asian markets with synthetic rhino horn will only increase demand for real horn and hasten the extinction of rhinos. And no one knows if practitioners of Chinese medicine would even accept the synthetic substitute. But that may not matter. While Pembient plans to sell its product clearly labeled as lab grown, the synthetic horn will almost certainly find its way into the secondary market, the company’s founders argue; from there no one would be able to tell the difference.

Can such a scheme work? Are Pembient’s critics right to worry that the company may stoke the market for rhino horn rather than snuff it out? Or are conservationists too stubborn to accept an outsider’s approach?

“Even Winston Churchill had the idea in the 1930s. He was saying that someday we’ll grow chicken breast without the chicken.”

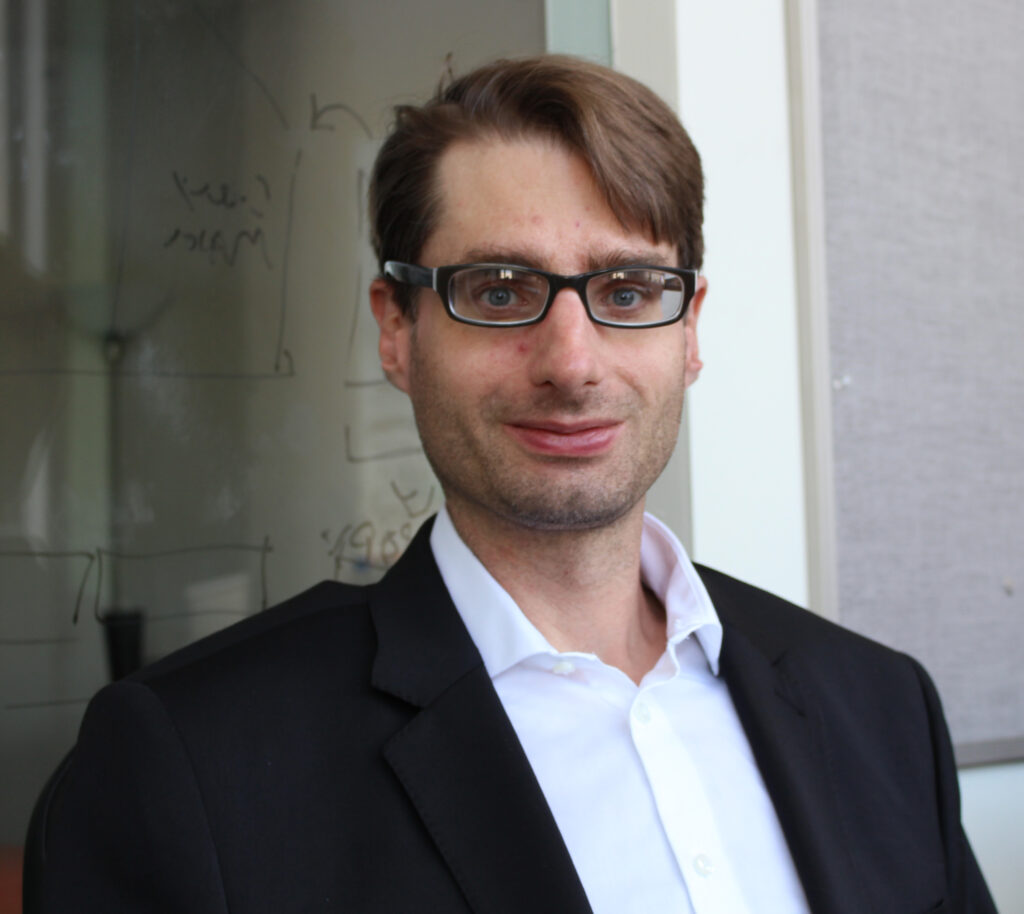

I was interviewing Matthew Markus, the 41-year-old CEO and cofounder of Pembient, about the future of artificial animal products. According to Markus, who holds a degree in genetic epidemiology, we are on the verge of a “biofabricated” world where nearly anything—skin, blood cells, hair—can be made in a laboratory, often with a 3-D printer. Markus doesn’t envision this technology being confined to hospitals or medical labs. He sees a world where even the most mundane consumer products are bioengineered.

“There are lots of things that you would use in your household . . . that would be fabricated from horn,” Markus said during our online video chat. He tapped the frames of his horn-rimmed glasses and mused that soon he might be wearing rhino-horn frames. Next he gestured to my shirt and suggested that one day we might all be wearing clothes with synthetic ivory buttons, just one example of a biodegradable substitute to the plastic materials that are now ubiquitous.

For Markus the coming biotech revolution isn’t just about saving animals from poaching; he believes that replacing many types of consumer plastics with lab-grown materials would be better for the environment. And rhino horn, natural or synthetic, just feels better than plastic.

“Horn is a nice material,” he remarked. “It warms very quickly to the touch, it’s very smooth, and it’s a lot like ivory, which has all these historical allusions to wealth and power.”

Matthew Markus, cofounder of Pembient.

Markus first came up with the idea of using biotechnology’s tools to undercut the market for rhino horn in 2014 while working at a software company. Before that he had worked on a project to determine the genetic makeup of mixed-breed dogs. When he read about the plummeting rhino populations, he thought he could use his knowledge of DNA and technology to address a more pressing matter. (Although rhino horns are not made of living cells, they still contain trace amounts of rhino DNA, just like human hair. Without the proper DNA traces, genetic testing could easily distinguish fake horns from the real thing.)

When Markus pitched his idea to a bioengineer who fabricates living tissue, she estimated it would cost $3 million to grow the horn on a biodegradable scaffold, using stem cells and keratinocytes to build it up molecule by molecule. Markus balked and instead sought a second opinion from a young biochemist he had collaborated with earlier in his career. The biochemist, George Bonaci, had worked in the hair-products industry and was intimately familiar with keratin’s properties. Instead of growing a perfect replica of a horn, Markus asked if Bonaci could cobble together keratin and the other ingredients of rhino horn that would simulate the look and feel of natural horn and could fool spectrographic and genetic tests. Bonaci thought that not only could he do it; he could do it on the cheap.

In early 2015 Markus and Bonaci founded Pembient, with Markus handling most of the business decisions and Bonaci in charge of the lab. Their goal was to biofabricate horns they could sell at $8,000 per kilogram, far less than the cost of natural horn. They believed that cost would go down as they scaled up production.

Pembient was soon accepted into a business accelerator, an arrangement where investors give start-ups financial and strategic support in exchange for equity. Within a couple of months Pembient had developed rhino-horn powder that had the right mix of ingredients. But Bonaci still struggled to find an affordable process for building a solid horn with that powder. He created a handful of prototypes using a 3-D printer, but each came up lacking. Some didn’t replicate the true texture of the horn, while others that looked right on the outside didn’t pass muster on the inside. Eager to get the business end of the company moving, Markus sought a market for Bonaci’s powder and looked to Vietnam.

Small prototypes of the synthetic rhino horn Pembient hopes to produce.

Markus and Bonaci discovered that the Vietnamese who used rhino horn would put it in practically anything. They washed their hair with it, rubbed it on their skin, and drank it in their beer. Bonaci recognized this behavior: the Vietnamese were mimicking a trend already popular in the West, where shampoos, facial creams, and other beauty products increasingly featured keratin, an ingredient alleged to strengthen hair and protect skin (although keratin in the West usually comes from chicken feathers or sheep’s wool). Within a year Pembient had started negotiating with a handful of Asian beverage and beauty companies to sell their bioengineered powder premixed with the companies’ products. The opportunities in Vietnam seemed boundless. Pembient began exploring other product lines, including rhino-horn cell-phone cases and chopsticks.

By May 2015 Western media had caught wind of their efforts, and the story went viral. The Guardian, a British newspaper, published a facetious-sounding headline that asked, “Can we save the rhino from poachers with a 3D printer?” That and other media attention brought a backlash from conservationists and environmentalists who saw Pembient’s owners as uninformed outsiders trying to solve a complex problem they did not understand. Markus didn’t help his case when he referred to biofabrication as “conservation 2.0” and told the outdated 1.0 conservationists their methods had failed and it was time to try something new.

“Pembient is trying to capitalize on the blood of rhinos for money, and their reckless behavior is as threatening as the poaching they claim to be addressing,” fumed conservationist Douglas Hendrie in a statement co-signed by 10 wildlife groups.

Later in an online interview with National Geographic, Hendrie, who oversees crime investigations for Education for Nature–Vietnam, recalled China’s one-off legal sale of elephant ivory and tiger parts in 2008. The sale was meant to lower demand, but it backfired: demand increased and led to even more poaching. Hendrie foresaw the same thing happening with Pembient’s scheme.

Wary of the bad publicity, the companies that had partnered with Pembient in Vietnam pulled out. After that failed venture Markus has seemed to tread more carefully and has made an effort to work within the existing conservation infrastructure. When I interviewed him, he was outside Johannesburg, where he was collecting rhino DNA samples and trying to establish a profit-sharing deal with the South African government. These bureaucratic steps weren’t necessary; Markus could have taken what he needed without the government’s blessing or used a sample from a rhino in a U.S. zoo, but he was wary of Pembient being seen as a “biopirate” looting South Africa for its natural resources.

At the end of 2015 Markus returned to Vietnam in search of a new approach. Through his research he found that the medicinal use of horn is actually a secondary market for something even bigger: carvings. Bowls, combs, spoons, and necklaces carved out of rhino horn are signs of wealth and are commonly exchanged as gifts among the elite. The leftover shavings from these carvings feed the medicinal market. Since making that realization the company has shelved the marketing of their powder and instead has concentrated on building solid, fully carvable horns that are indistinguishable from the real thing.

Pembient’s willingness to rethink its approach has persuaded at least some conservation organizations to do the same. A study released by TRAFFIC in April 2016 weighed the pros and cons of biofabricating wildlife products and concluded that the conservation community’s response was over the top. The authors of the study, Gayle Burgess and Steven Broad, wrote that it “would be rash to rule out the possibility that trade in synthetic rhinoceros horn could play a role in future conservation strategies.” Unlike government-sanctioned legal sales of animal products, which have proven only to temporarily deflate the value of poached animal parts, bioengineered horns could be a permanent alternate source of “real” horns, as long as consumers accept them.

While some conservationists have warmed to Pembient’s approach, other critics lump Pembient in with rhino ranchers, such as South African farmer John Hume, who has been trimming and storing the horns of his privately owned rhino herds while lobbying to end the ban on the sale of rhino horns. Most conservationists have so far resisted farmed horn because they believe it would increase demand and only serve to enrich the ranchers. Ranchers argue that responsibly harvested horn could undercut the black market while providing money to protect rhinos from poachers.

Markus has separated himself from rhino farming by pointing out that his business is much more scalable; while rhino ranchers would only be able to sell a relatively small amount of horn that could fuel more demand, Pembient theoretically has no upper limit to its production: it can flood the market until horn is devalued. Finally, Markus contends that rhino farming still exploits animals that should be kept free and whole, whereas biofabrication would eventually take the rhino itself out of the trade entirely.

But Markus can’t seem to shake the one critique he finds most frustrating and that he believes is immaterial: what if Pembient’s horn is too convincing? In other words, what if criminals who poach real rhinos claim they are carrying Pembient’s product if caught? How will law enforcement distinguish between poached and fabricated horns? Markus’s answer: virtual rhinos.

If the majority of the market already consists of fake rhino horn and people don’t notice, how would adding more fake horn to the supply change anything?

Inspired by the FBI’s criminal database CODIS (Combined DNA Index System), the University of Pretoria has established a database called RhODIS (Rhino DNA Index System) with the goal of registering the genetic code of every rhinoceros in South Africa. Rather than just copy the genes of existing rhinos, Markus wants to scramble those genes until every horn Pembient produces has unique DNA. His virtual “herd” of rhinos would exist parallel to the real rhinos in RhODIS, and law enforcement would be able to easily check if someone was smuggling a horn that had belonged to a living rhino or to a virtual one.

But the black market is complicated and can behave unpredictably, and there are ele-ments that continue to perplex conservationists and law enforcement. Markus himself noticed something strange when examining the consumption of rhino horn. By combining trafficking data with interviews he conducted in Vietnam, he estimated that total demand for rhino horn could grow to 300,000 kilograms per year. But only about 6,000 kilograms of horn were being smuggled out of Africa annually. The math just didn’t add up. It seemed the people he had talked to were either lying or somebody had already flooded the market with fake rhino horn.

I decided to find out if anyone in Philadelphia’s Chinese-medicine community could explain the puzzling discrepancy Markus had discovered. Were vendors knowingly selling knock-off rhino horn? I wasn’t sure where to start; so I wandered through Chinatown until I spotted a sign for Long Life Chinese Herbs. Through the window I saw a glass counter filled with hundreds of white pill bottles in front of what looked like an enormous card-catalog cabinet, the kind once found in libraries. From the sidewalk I could smell the earthy aroma of herbs. I walked through the door and asked the woman at the counter if she knew where I could find rhino horn. She looked me blankly and asked if I was there to see the office space for rent.

I shook my head and tried again to explain what I wanted.

“Rhinoceros horn. Rhino horn. From a big animal in Africa, and it has a horn on its head.”

I stuck my arm out from my forehead to mimic what a horn looked like.

“Elephant?”

“It’s smaller than an elephant, and it has like a unicorn horn on its nose.”

“What do you want to buy?”

“I’m interested in finding shavings, or powder—”

“No, nobody can sell that.”

She started opening drawers from the massive cabinet behind her, showing me all variety of dried leaves and seeds. But no rhino horn. When I asked who else I should talk to, she told me that she didn’t understand English and that I should leave.

Back in my office I phoned a few more Chinese-medicine shops and got the same dismissive response. Finally, a receptionist at one place suggested I contact Cara Frank at Six Fishes, a Chinese-medicine and acupuncture clinic in South Philadelphia.

Frank trained in Chinese medicine in Beijing in the late 1980s and has been practicing and lecturing on the subject for more than 20 years. She seemed happy to talk to me, and she even had a little vial of rhino horn she bought long ago, although she admitted she didn’t remember where she got it and had no idea whether it was real. I asked whether I could come and see it. Of course, she said.

I arrived at Six Fishes before Frank’s first patient of the morning was due. We went downstairs, where she had a cabinet similar to the one I had seen in Chinatown. After rummaging through a crate piled high with old bottles and plastic bags, she found the rhino horn and handed it to me.

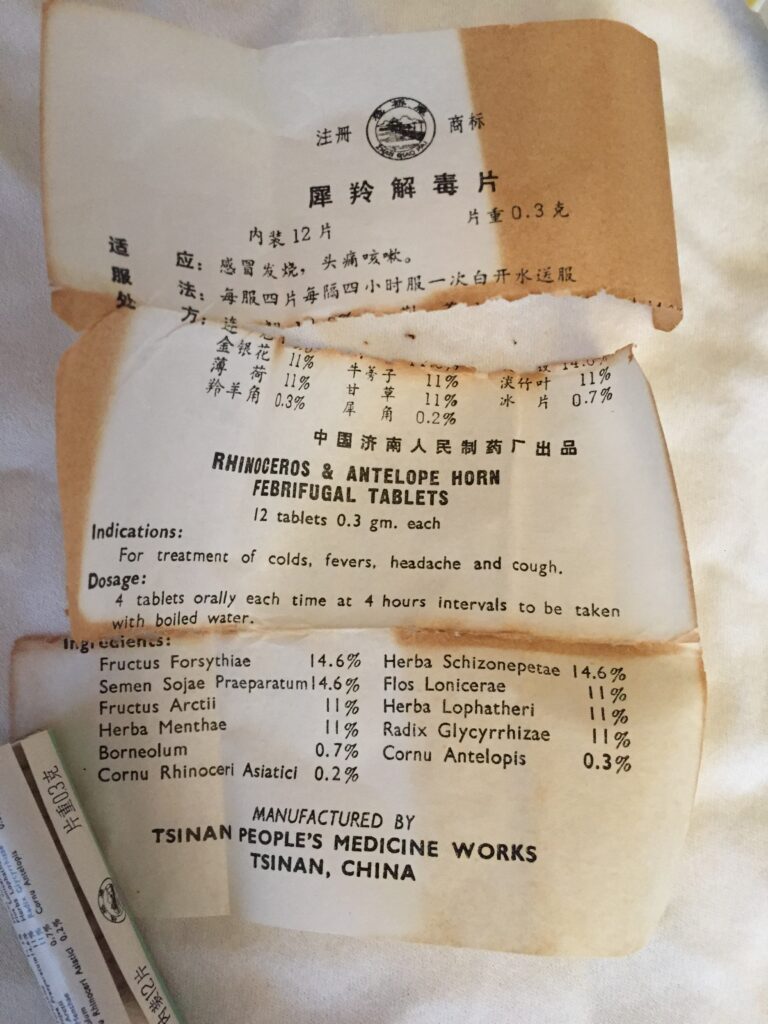

The ingredient list for fever-reducing tablets include rhinoceros and antelope horn.

It looked like an ancient roll of Smarties, its paper wrapper brown and peeling. Inside were about a dozen beige tablets. The following ingredients were listed on the label:

Semen Sojae Praeparatum—14.6%

Herba Schizonepetae—14.6%

Fructus Arctii—11%

Herba Menthae—11%

Flos Lonicerae—11%

Herba Lophatheri—11%

Radix Glycyrrhizae—11%

Borneolum—0.7%

Cornu Antelopis—0.3%

Cornu Rhinoceri Asiatici—0.2%

Cornu rhinoceri is Latin for rhinoceros horn. I was surprised by the tiny percentage of it in the tablets, but Frank explained that Chinese medicine rarely uses a single substance to treat any one symptom. In any case she would never prescribe rhino horn and had only bought the tablets as a novelty item to show her students at Six Fishes.

In the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing, a foundational text of Chinese medicine written nearly 2,000 years ago, rhino horn is an important substance that treats “hundreds of toxins, gu [poison] influx, evil ghosts, and miasmic qi.” According to the text the horn also kills poisonous plants, destroys snake toxins and the feathers of a poisonous bird, “eliminates evils, and prevents confusion and oppressive ghost dreams.”

As times changed, so did Chinese medicine practitioners’ use of rhino horn. In 1986 Taiwanese pharmacist Hong-Yen Hsu, whose research blended Chinese and Western approaches to medicine, published Oriental Materia Medica. Hsu’s book provides an updated list of ailments rhino horn can treat, including hemorrhaging, fever, loss of consciousness, delirious speech, and carcinoma. But by the time Hsu’s book was published, rhino-horn trafficking had been banned for nearly a decade, and a replacement was needed.

In the basement of Six Fishes, Frank opened a plastic tub and what looked like pieces of bark fell out. On closer inspection I saw that the “bark” was actually thin, fibrous shavings of horn. It was sourced, Frank said, from domesticated water buffalo. The pieces crackled when I touched them and looked remarkably similar to images of rhino-horn shavings I had seen online. According to Frank, water-buffalo horn had been an acceptable but less powerful substitute for rhino horn in Chinese medicine even before the latter was made illegal, and both are said to treat similar diseases. I wondered if water-buffalo horn was being passed off as rhino horn in Southeast Asia. Frank said she was certain it was.

Many conservation groups had come to the same conclusion. In 2012 TRAFFIC reported that an estimated 90% of all “rhino horn” passing through Vietnam was probably water-buffalo horn. That would explain the mathematical inconsistency Markus found in his data between reported use and the much smaller supply of authentic rhino horn coming out of Africa. But if that was true, Pembient’s entire plan of action seemed destined to fail. If the majority of the market already consists of fake rhino horn and people don’t notice, how would adding more fake horn to the supply change anything?

When I spoke to Markus about the matter, he told me that TRAFFIC’s finding were an impetus to bring Pembient’s bioengineered whole horn to market even faster, before technology makes it easy to spot the natural fakes.

Markus believes that the average consumer will eventually be able to test a substance for authenticity before buying it—even a black-market product like rhino horn—probably with a device that connects to a smartphone. When that technology arrives, there will be even more pressure on the rhino population as consumers refuse to buy substitutes. While these miniaturized testing technologies are not yet available, theoretically they would differentiate rhino horn from water-buffalo horn by, for example, identifying a species-specific genetic “fingerprint.” Only something as sophisticated as Pembient’s proposed product would be able to fool such tests.

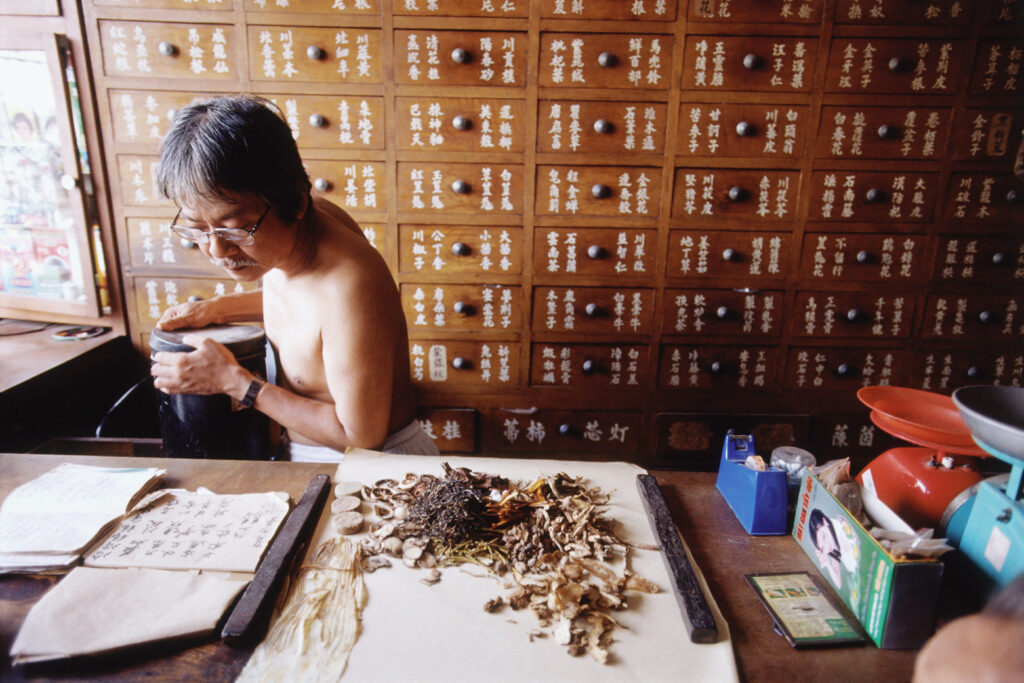

A Chinese medicine dispensary in a Mekong Delta town in Vietnam.

Back at Six Fishes, Cara Frank mentioned she was having trouble finding water-buffalo horn shavings in the United States. I asked her if she would ever consider using Pembient’s rhino horn as a replacement if she couldn’t find buffalo horn. Her response was an adamant no.

“I try not to buy GMO food because I don’t know what it’s going to do. I don’t know what this would do,” Frank said. After considering the idea for a minute, she added, “I mean, they might be able to replicate something, but it’s just not going to happen that you can make something that is as nuanced as a real rhino horn medicinally.”

Instead, Frank would likely do what Chinese-medicine practitioners have done when other animal products, such as tiger bones and pangolin scales, have become unavailable: isolate the active ingredients and find replacements.

Of course, Frank’s wariness of lab-grown rhino horn is only representative of one practitioner. When Pembient conducted a survey in Vietnam in 2014, it found that 45% of people polled would consider using biofabricated horn instead of authentic rhino horn, whereas only 15% said they would prefer water-buffalo horn as a replacement.

And if Pembient’s horn is molecularly indistinguishable from real rhino horn, why does it matter where it comes from? Frank mentioned that something intangible, a sort of essence she called jing, exists in every living being. If Pembient’s horn doesn’t come directly from a rhino, it wouldn’t have that essence, and therefore it wouldn’t be as effective medicinally as real horn.

What would be the West’s response if, say, India’s Hindu population demanded we give up our hamburgers? Is there a double standard here?

Perhaps the essence Frank spoke of isn’t so different from how many of us think about food. When acclaimed chef Richard McGeown unveiled a hamburger patty made from lab-grown beef in 2013, there was something about the creation that many people found creepy. The revulsion was hard to articulate.

The possibility of a world built by biotechnology as Markus imagines it—where everything from our clothes to our food is developed in a laboratory without the use of animals or petroleum—hinges on the public’s acceptance of human-made substances that are uncannily like, even identical to, their natural counterparts.

When I spoke with Markus, he mentioned he was trying to be more responsible with his food choices. Like many of his colleagues in the biotech world, he is cutting meat out of his diet. “I’m not quite vegan yet. I’m vegetarian, maybe pescatarian.”

For him that would all change if laboratory meat became widely available. But the question remains: how many vegetarians and vegans would be willing to eat meat and dairy products grown in a lab? If their food choices are motivated by the treatment of animals and the environmental consequences of the factory-farming system, Markus contends they should have no issue converting.

Perhaps the thorniest obstacle to overcome is cultural. To save the world’s rhinos it may seem reasonable to expect Chinese-medicine users to forgo rhino horn. But what would be the West’s response if, say, India’s Hindu population demanded we give up our hamburgers? Is there a double standard here?

Markus argues that we shouldn’t judge people for 2,000-year-old cultural practices of eating rhino horn or tiger organs without questioning our own use of animals. Are the lives of a select list of endangered species more valuable than the lives of the tens of billions of animals slaughtered for food each year? Does the permanent loss of a single species outstrip the ecological toll of our animal-farming practices? Whatever the answer, Markus believes it is more realistic to use technology to allow Westerners to continue eating their hot dogs and Vietnamese to continue eating their rhino horn than to force everyone to change their practices.

Even if Pembient succeeds in reducing the price of rhino horn, that alone won’t be enough to save the world’s rhino population. The uptick in demand for rhino horn in Vietnam since 2008 is only the most recent chapter in more than a century of environmental devastation and poaching. Lawmakers and conservationists will need to set aside and protect enough land for rhinos to roam without human interference. But human population growth, industrialization, and agricultural expansion make setting aside such resources difficult.

It remains to be seen whether Pembient can construct a horn good enough to fool advanced testing and whether the company can convince users of Chinese medicine to try it. It is also unknown if biofabrication will replace the animal products we eat and wear. Markus, for his part, is hopeful that someday an animal’s worth won’t be judged by its tangible value to humans—be it as a steak on a grill, a trophy to be hunted, or a photo op for tourists.

“What I would like for the future is protected areas in which there is no value to go and cull those animals for human use,” he said. “We would just have wild, free areas and an abundance of biofabricated wildlife products. An abundance of ivory, [where] everything we have is ivory, everything we have is made of rhino horn. It’s all over the place.”