Leslie Tomory. Progressive Enlightenment: The Origins of the Gaslight Industry, 1780–1820. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. 348 pp. $28.00.

To chemists of the past the distillation of coal in the absence of air was among the most critical of all processes. The conversion into the fourfold outputs of coke, gas, tar, and “ammoniacal liquor” symbolized the utility of their science. After all, tar was the basis of the organic chemical industry, coke fueled furnaces and was a staple of the steel industry, and liquor was the basis of fertilizers. And then there was coal gas. Unlike today’s “natural gas,” which is mostly methane, coal gas was a complex mix of compounds and elements that included methane and ethylene, hydrogen and nitrogen, poisonous carbon monoxide, and odiferous hydrogen sulfide—which gave the gas its characteristic smell.

Coal gas was used for lighting, heating, and cooking from the early 19th century, first in Britain, then in the rest of Europe and in North America. By the end of the century it was so ubiquitous that the substance itself was considered banal. Few historians of technology have noticed the depth of its significance or have charted its development, in contrast to the attention they’ve paid to steam power. The pioneers, technologies, and manufacturers of coal gas have attracted little interest; its competition with electricity has been virtually ignored. And if literary historians took notice, it was only to explore its use as a favored means of suicide.

Leslie Tomory is intent on overturning this lamentable state of affairs. He shows that the development of gas in the early 19th century was crucial to key sectors of the Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain during the late 18th century. While Progressive Enlightenment deals with a narrow historical period, it maintains a wide intellectual range. Four related issues are addressed: the early development of gas lighting as a concept at the end of the 18th century; whether gas technology grew out of 18th-century science, thus suggesting the Industrial Revolution depended on the discoveries of the Enlightenment; the development of gas lighting technology for textile mills in the work of the steam engine pioneers Matthew Boulton and James Watt; and finally, and most extensively, the business model of London’s Gas Light and Coke Company, which developed both a system of gasworks and a consumer market for domestic services and street lighting.

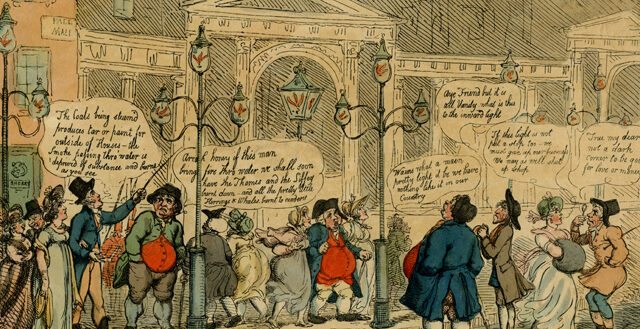

The lead in gas technology was taken first by England’s William Murdoch, who promoted the technology at Boulton & Watt, and by Murdoch’s London competitor, the German-born Frederick Albert Winsor, and what became London’s Gas Light and Coke Company. Tomory shows how Winsor and his business partners and managers accessed capital through the joint stock company for the Gas Light and Coke Company, giving his adopted country a real advantage over less capitalistically developed competitors overseas and against Boulton & Watt, which focused on individual factories. The Gas Light and Coke Company by contrast built a network to supply gas to streetlights and domestic consumers using water mains as a model.

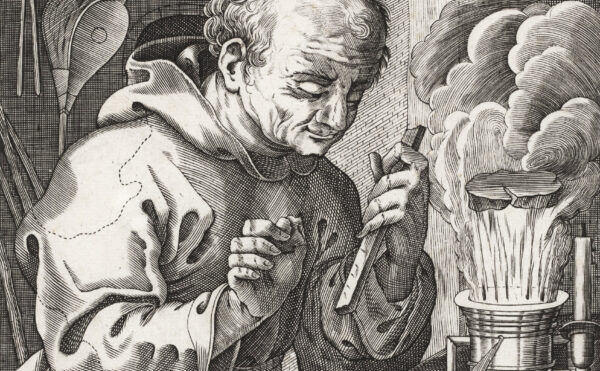

Two features of this book stand out and take the subject substantially forward. First is the close study of Boulton & Watt, where Tomory links the concept of the industrial gasholder developed by the company to the development of apparatus by 18th-century chemists. Antoine Lavoisier plays a particular role here: he developed instruments to measure and stores quantities of gas. The argument for the close linkage between the work of Lavoisier and Boulton & Watt is made well. As to the Industrial Revolution’s dependence on the Enlightenment, that is less clear. Tomory has established the transmission of apparatus from the science to the technology, but that is not enough to show that scientific theories were themselves key to the development of the industry. What constituted coal gas and its lighting potential were empirically observed rather than theoretically determined. Tomory uses the phrase “Enlightenment ideal” several times as if it were as hard and unproblematic as a lump of coal. There is a gap here that should provoke further thought.

The second and more general contribution of Tomory, who trained as an aerospace engineer, is to our understanding of the engineering of the early gasworks systems. He brings an engineer’s sensitivity to a subject more typically studied in recent years by economic historians. There is a close study of regulators and valves, whose development was crucial to the growth of the gas network; a gas company’s ability to prevent nonpaying customers from receiving gas was a key element of economic success. Chemists who take gas as their professional achievement take note: for all his reference to the Enlightenment and public science, Tomory shows that the development of the gas industry, even in its early days, required the confluence of engineering and commercial skills, as well as that ever valuable commodity, luck.