The U.S. Civil War created an insatiable appetite for explosives, and companies both new and established rushed to meet the seemingly endless demand. As the war drew to a close, the supply of explosives soon far exceeded demand, and the industry plunged into turmoil. DuPont, the U.S. pioneer in explosives, resolved to bring order back to the industry by absorbing and eliminating as much of its competition as possible. As a result DuPont became the largest explosives monopoly in the United States.

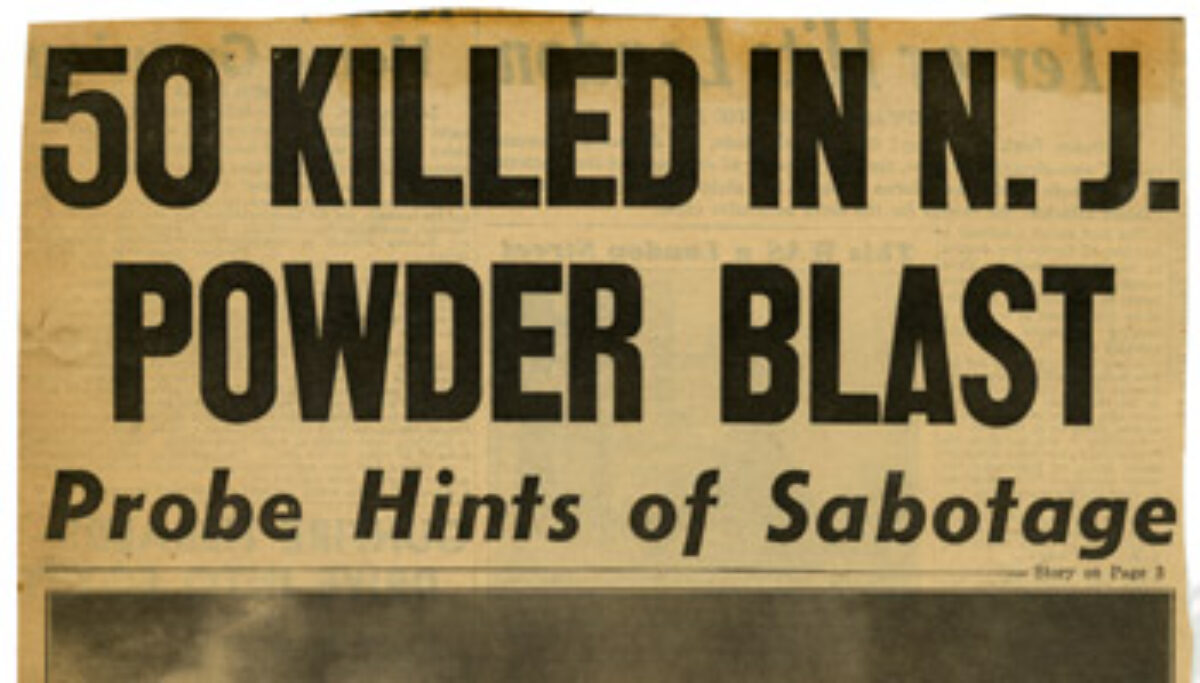

By the turn of the 20th century DuPont and its subsidiaries controlled nearly two-thirds of the entire explosives market. Trust-busting crusaders of the time, who had made their names dismantling industrial monopolies in the railroad, steel, and oil industries, turned their attention to DuPont. In 1907 the Department of Justice filed a criminal antitrust suit against the company. The suit went to trial the next year, and after three years of arguments the U.S. Circuit Court for the Third District ruled that DuPont was in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. DuPont was told to prepare a plan for its own dissolution. The company negotiated a settlement with the government, agreeing to divide its explosives industries between itself and the newly formed Atlas Powder and Hercules Powder companies.

With assets handed down from its parent, Hercules quickly established itself as one of the primary explosives manufacturers in the nation, just in time for a new—and global—conflict. World War I led to profits and growth, but Hercules quickly realized it could not depend on wartime contracts for its survival. After the war Hercules turned itself into a chemical producer, one whose products eventually spanned specialty chemicals, petrochemicals, engineered polymers, and even aerospace technologies. But a link to its explosive past remained; in the 1950s Hercules began building rockets for the military and in the 1990s built rockets for the civilian satellite market. Hercules continued to operate until 2008, when it was acquired by Ashland.

The images for this photoessay come from the Hercules Archives at the Science History Institute.