In the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear power developed into two distinct identities in the public mind: the “destructive atom” and the “peaceful atom,” the latter a powerful new energy source for a new era. Located between these two poles, Atomic Age jewelry styles from the 1950s—with their fanciful representations of swirling atoms and electrons, starbursts and sunbursts—represent the domestication of the atom, mass-produced for the fashion-conscious female consumer of the time.

Atomic Age jewelry presents a material example of how the American fashion industry cashed in on the atom and promoted a feminine ideal that bolstered the country’s postwar conservative values. At the same time, it captures the public’s fascination and fears about nuclear power and weapons testing in the wake of World War II.

In the emotionally charged weeks after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a time of elation and shock, American media introduced nuclear energy. Among the flurry of news about the bombings, the cover of the New York Times Magazine from August 12, 1945, presented an aerial-view photo of the gigantic billowing atomic cloud over Hiroshima. The accompanying feature proclaimed, “We Enter a New Era—the Atomic Age,” and informed its readers of the power science had unleashed “for better or for worse.” Here readers also encountered the “peaceful atom,” as shown in an illustration of Earth hovering in a cosmic horizon filled with other planets and symbols of atomic energy. Through sci-fi visuals and accompanying text readers could imagine a marvelous future where nuclear power could be harnessed to benefit humanity in a new age of postwar peace and prosperity. This utopian message was presented only days after nuclear weapons had leveled two Japanese cities.

The New York Times article aptly encapsulates both the anxiety and optimism that would come to characterize 1950s American society. On the one hand, the magazine cover graphically delineates the horrific implications of the destructive power of atomic energy. On the other hand, its article outlines the awesome energy stored within the atom, stating it “may well be the basis of an entirely new kind of civilization.” The fundamental (and not so subtle) message that the New York Times delivered was that nuclear power, properly harnessed, could invigorate modern living and lifestyle, a theme that ran throughout the Cold War era. Atomic energy, for better or for worse, was here to stay.

Weeks earlier, on July 16, 1945, the U.S. military conducted a test blast at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range in southern New Mexico. Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell described his amazed reaction to the press: “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity of many times that of the midday sun. It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined.”

Farrell’s vivid description frames the blast as a thing of devastating beauty—a notion expressed in silk and taffeta by American haute couturier Adrian, whose “Atomic 50s” signature collection appeared in the April 15, 1950, issue of Vogue.

Atomic Age jewelry presents a material example of how the American fashion industry cashed in on the atom and promoted a feminine ideal that bolstered the country’s postwar conservative values.

The elegant evening dress featured in the Vogue advertisement is a sartorial embodiment of atomic detonation: the columnar body of the gown rises into enormous billowing folds at the shoulders, designed to evoke the mushroom-shaped cloud formed after a nuclear explosion. Adrian was renowned for his dramatic designs as MGM’s head costume designer and for designing sophisticated attire for such glamorous Hollywood stars as Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, Jean Harlow, and Adrian’s wife, Janet Gaynor. (Adrian’s best-known design is likely Dorothy’s ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz.)

While films and magazines provided women with a template for good taste, chic was made affordable and attainable through home sewing and “fashion” or “costume” jewelry. Just as the retail fashion industry and home-sewing culture looked to Hollywood for leadership, designs produced by the fashion-jewelry industry closely followed trends established by high-end jewelry houses. Typically, fashion jewelry was factory produced and used materials that mimicked or resembled precious materials, like rhinestones, molded glass, faux pearls, and gold-plated or silver-toned metals (which were often rhodium plated). Fashion jewelry was widely advertised in magazines and retailed at such department stores as Sears and Roebuck, Marshall Fields, and Saks Fifth Avenue.

A defining element of 1950s fashion came from the New Look, a hugely influential and ultrafeminine style based on an extremely curvaceous silhouette introduced by Christian Dior in 1947. Dior’s designs rejected the severely tailored, shoulder-padded, slim-skirted suits that were typical of World War II fashion. Dior’s description of the New Look conjures up an image of metamorphosis from wartime austerity to postwar femininity: “I turned [women] into flowers with soft shoulders, blooming bosoms, waists slim as vine stems, and skirts opening up like blossoms.” The New Look prevailed throughout the 1950s as a popular and widely copied style. And inasmuch as the New Look was a statement that wartime rationing was finally over, it also played an important role in postwar economic recovery: the excessive amount of fabric required to create the New Look skirt helped restart the French textile industry in the immediate postwar period.

The smooth, undulating silhouette that was the hallmark of the New Look was in fact engineered by undergarments that reshaped female bodies to conform with the exaggerated curves—full bust and full hips, emphasized by a cinched waist—dictated by the feminine ideal. This shape was made possible with elastic and nylon. These scientific innovations in textiles revolutionized the postwar undergarment industry and were extensively used in the corselets, cinches, and brassieres that molded the female form into shapely proportions. Crinoline petticoats made of nylon or nylon blends were worn under the skirt to create its bouffant blossomlike shape. The ultrafeminine emphasis that defined 1950s fashions and its promotion as the universal ideal of beauty constituted a kind of blueprint for reconfiguring social and gender roles in the 1950s that had been disrupted by the war, when women performed traditionally male tasks in the workforce.

To achieve this transformation the fashionable woman of the 1950s required one more thing to complete her “look”: jewelry. Rules of etiquette dictated that no woman’s ensemble was complete without a coordinating suite of earrings and a brooch, and possibly a necklace, rings, and bracelets. Depending on its placement a brooch might draw attention to a soft, rounded shoulder or the delicate collarbone area, thus showing off the curve of a neckline or accentuating the ruffle of a scarf. Earrings drew attention to the wearer’s neck, jawline, face, and hairstyle. A necklace accentuated the feminine swell of the bosom. Knowing how to dress well was synonymous with social acceptance. Jewelry that represented Atomic Age motifs was a popular fashion choice for accessorizing daytime ensembles.

No singular style defines Atomic Age jewelry. It is a hodgepodge of designs representing explosions, swirls, stars, and sunbursts based on permutations of an atomic theme, and it reflects the culture of abundance synonymous with this era. Whimsical interpretations of atomic motifs are also found in the textile prints used in clothing, furniture upholstery, carpets, and curtains, as well as in linoleum, china, and flatware patterns—all stuff of the perfect home.

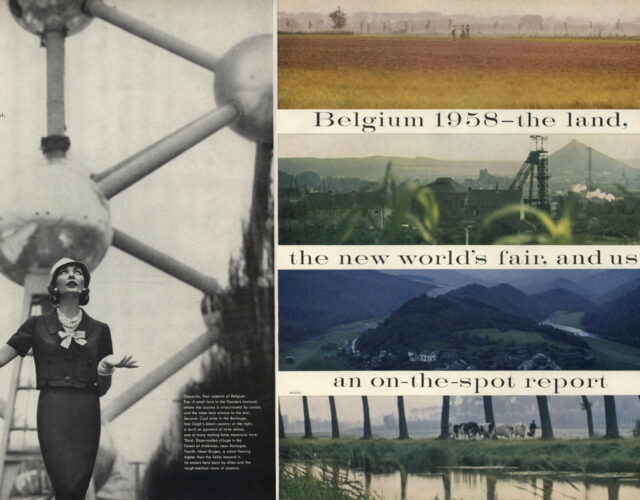

By the close of the 1950s the material culture of the Atomic Age had become fully infused with popular culture, embodied in the colossal Atomium, “the symbol of the new World’s Fair.” As an edifice the Atomium was part of a world’s fair tradition of erecting monuments to progress that began with Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, the progenitor of all world’s fairs. The Eiffel Tower, for many years the world’s tallest freestanding building, was erected for the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. World’s fairs were ongoing international exhibitions that usually ran for 8 to 12 months and were a forum for European and American nations to present their ideas of progress. World’s fairs engaged the public with exhibits of the latest industrial, scientific, technological, and artistic achievements of the participating nations. And each world’s fair sought to define utopian visions of the future.

The Atomium, chosen as the symbol for the world’s fair held in Brussels in 1958, was the physical embodiment of the “peaceful atom.” It was a 335-foot-tall, stainless-steel architectural monument, presented to the world as a futuristic home. The large globes that studded the interstices of the Atomium were habitable spheres that visitors accessed by way of escalators running through connecting tubes. The Atomium was the future made material and the “peaceful atom” made manifest.

Vogue reported “on the spot” from Brussels, capitalizing on the world’s attention and interest in this world’s fair to promote American fashion in an international arena. A feature article from the April 15, 1958, issue presented the fashionable American woman in a variety of social situations, wearing the appropriate outfit for each one. The image chosen to kick off the Vogue piece is a masterpiece of composition. The model is posed ostensibly to check the sky for rain, but in her upraised palm she also appears to hold a sphere of the Atomium in a moment of calculated playfulness. Nor was the choice to complement her outfit with large pearl earrings a coincidence; they echo the globular, giant, steel-ribbed Atomium behind her. Indeed, enormous pearl earrings (faux or real) were a staple that characterized the fashionable woman of the 1950s. At once elegant and sassy,Vogue appropriated the “peaceful atom,” transforming it into a fashion statement about American glamour abroad.

Atomic-themed designs were but one of many choices available to the 1950s consumer, finding their place among plaid patterns, geometric forms, and stylized flowers. That said, the prevalence of atomic design in the postwar American home is manifested in advertisements of the time as well as in the quantity of collectible items currently available on eBay and Etsy (usually scavenged from “mom’s basement” or “grandma’s estate”). Today online vendors have created a new market for bygone things in which the sheer volume of stuff on the move points to the past popularity and consumer appeal of the atom in 1950s home furnishing and fashion. Atomic Age jewelry takes its place as a Cold War relic alongside science-fiction movies and literature, children’s chemistry sets, and fallout shelters, whose signs can still be seen outside of apartment buildings, churches, and universities.