On the Backs of Cod

Before the collapse, cod was a way of life in Newfoundland.

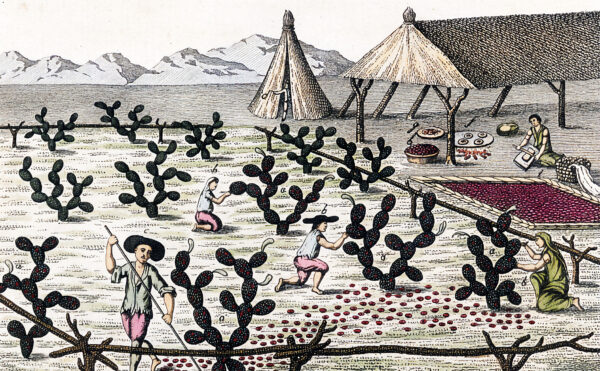

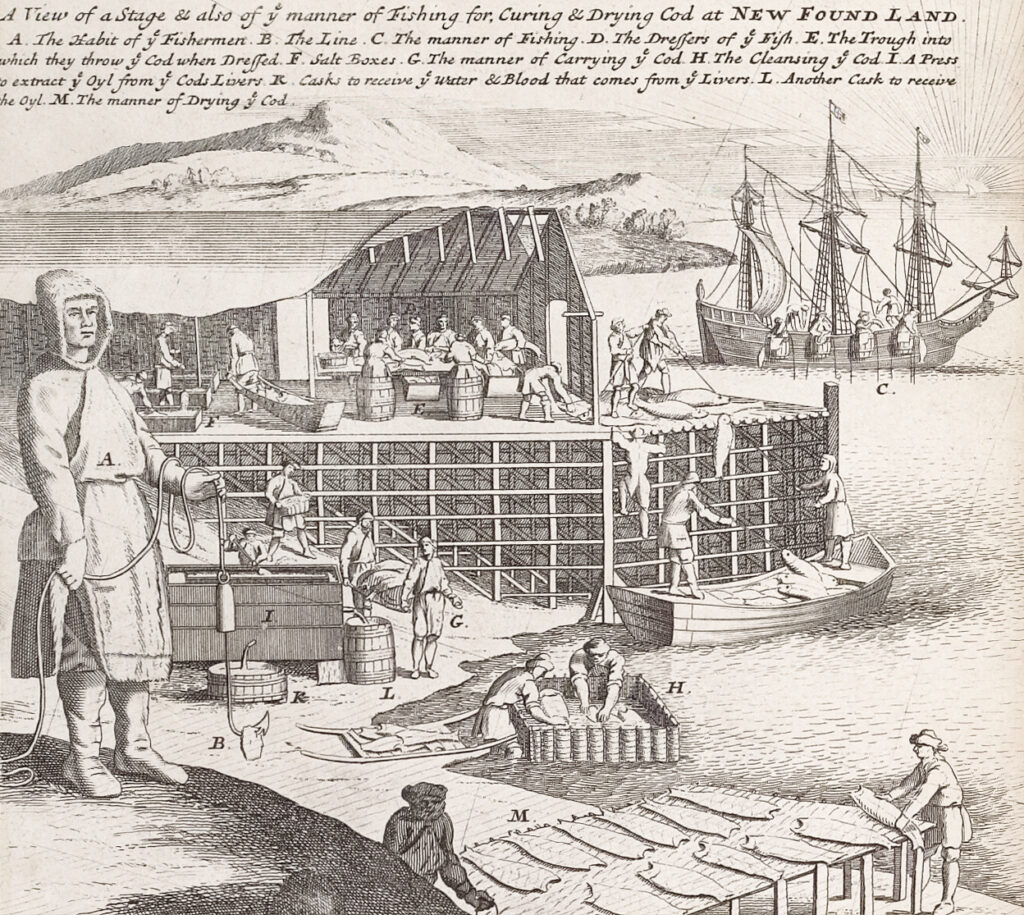

Since the Middle Ages, the fish had been caught by Vikings and Basques off North America’s Atlantic coast, seizing on a bounty upon which Indigenous peoples had long relied. The English, Spanish, and Portuguese eventually found this “new world,” and by the mid-16th century, 60% of the fish eaten in Europe was cod—much of it drawn from the banks of the northwest Atlantic.

There are more than 200 species of cod, almost all of which flourish in the cold saltwater of the northern hemisphere. But the Atlantic cod is a special creature. It was prized for its alabaster flesh and low fat content, which made it ideal for preserving, either by hanging in the brittle winter air, as the Vikings did, or curing in salt, as the Basques did. High in protein, its dehydrated meat could power a journey at sea—or a burgeoning economy. Omnivorous and eager to take the bait, it was easy to catch. It was large, reportedly reaching up to six feet and 200 pounds in some 19th-century landings, although the more typical 25 pounds was still generous.

Most important, cod was abundant. It released millions of eggs when it spawned. When John Cabot landed in North America in 1497, he found its rocky coastline swarmed by Atlantic cod. After he claimed for England what he called New Found Land, tales spread of his men catching cod by sinking baskets into water so packed with fish his ships could barely move.

The legend of cod’s abundance persisted. In 1873, French novelist Alexandre Dumas wrote that if every egg reached maturity, within three years “you could walk across the Atlantic dryshod on the backs of cod.” In 1885, the Canadian Ministry of Agriculture said it was not only impossible to exhaust the cod supply, but even to make a noticeable dent in it. “Unless the order of nature is overthrown, for centuries to come our fisheries will continue to be fertile,” the ministry declared.

Unfortunately, humans have a long history of overthrowing nature.

In the 19th century, cod fishing began to industrialize off Newfoundland’s coast. Fishermen began longlining, stretching fishing lines up to five miles and dotting them with hooks every three feet. By the early 20th century, steam trawlers were hauling in six times what a sailing ship could capture in offshore waters.

The midcentury invention of the freezer sealed the cod’s fate, opening the door to 450-foot-long international factory ships that could hold 4,000 tons of fish and stay at sea for months at a time. Between 1959 and 1968, cod landings in the province went from 360,000 tons to 810,000, roughly 80% of which came offshore. The Atlantic cod didn’t stand a chance against these voracious trawlers; few could evade their nets long enough to reach breeding age. From 1962 to 1992, the biomass of the species dropped by 93%.

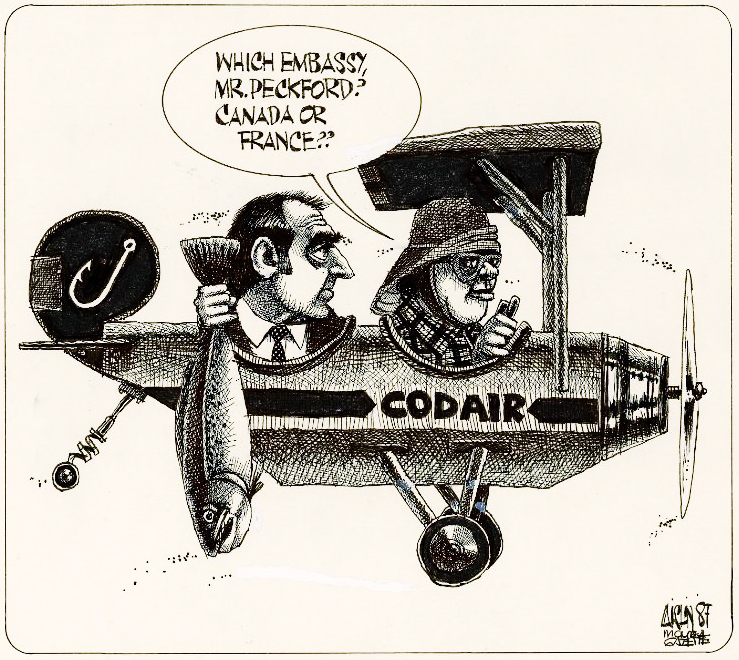

Newfoundland’s fishermen knew they were doomed, but the government’s response was still unimaginable. On July 2, 1992, inside a ballroom at St. John’s Radisson Hotel, John Crosbie, the outspoken minister of Canada’s fisheries and oceans, made a startling announcement. As angry fishermen stormed the doors of his press conference, he declared a two-year moratorium on fishing cod. In a province of some half-a-million people, it effectively put 30,000 out of work, many of them descended from families that had spent two centuries fishing the Grand Banks for their livelihoods.

Despite such drastic measures, the cod population didn’t rebound. The government extended the moratorium year after year. Several fishing towns resettled, and the province’s population fell 10% within a decade. It was a tragic ending to a story of abundance and prosperity—just the sort that an outspoken California ecologist had been warning the world about for three decades.

Ruin Is the Destination

By the time Newfoundland’s cod industry collapsed, Garrett Hardin had already become a household name among environmental scientists. His cautionary tale, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” offered generations a framework for understanding the type of natural resource exhaustion seen in Newfoundland.

Born in Dallas in 1915 and raised in the heartland, Hardin credited much of his perspective to lessons learned on a family farm in Missouri. Equally formative were undergraduate studies in zoology at the University of Chicago, where the early ecologist W. C. Allee introduced him to the theories of Thomas Malthus, the 18th-century English economist who argued that human population growth tends to outstrip the food supply.

At Stanford, Hardin took up the microscope to explore the limits of population growth among paramecium and the ecology of other single-cell marine organisms while earning his PhD in 1941. For a time after graduating, he researched methods to produce food from algae, hoping it might help feed an increasingly hungry world, but concluded the idea was unworkable. He found success, instead, with a widely read biology textbook that delivered him tenure at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the chance to do what he most wanted—to write, rather than research.

“Tragedy,” the 1968 essay in Science that carried Hardin’s voice around the world, considered the strain a global population boom was putting on the planet. In it, he referenced Malthus in claiming that it is human nature to deplete a shared resource, or commons, past the point of recovery. To illustrate his theory, he described a metaphorical pasture shared by a group of farmers—an image drawn, like the essay’s title, from an 1833 lecture by English political economist William Forster Lloyd.

With no restrictions on the number of cattle allowed to graze the pasture, Hardin suggested each herdsman would add to his herd, compelled by the knowledge that others would inevitably do the same to improve their own lot. Driven by a logic that has guided humans’ thinking since the dawn of agriculture and private landownership, each farmer would take, take, take from the land until nothing remained to be taken.

“Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons,” he wrote.

Hardin saw inexorable tragedy everywhere he saw shared resources: pollution of the air and water; overcrowding of the National Park System; overgrazing cattle on the Western ranges; even the abuse of free parking. In the oceans, too, “species after species” of fish and whale were brought closer to extinction by a misplaced belief in the inexhaustibility of resources and the universality of rational self-interest. Such pessimistic conclusions were troubling, even for Hardin himself. “I kept trying to escape from them, and I just couldn’t,” he later reflected.

For many who gravitated toward “Tragedy,” it spoke to a deep truth about human societies. As Aristotle had once written, “What is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it.”

The essay was an immediate success, prompting Science to issue hundreds of reprints that sold out in a matter of weeks. In a few decades’ time, it found its way into more than 100 anthologies on ecology, environmentalism, health care, economics, law, political science, philosophy, geography, psychology, and sociology. It remains one of the most-assigned texts in U.S. universities and is among the most-cited publications in climate change research, referenced alongside work by Edmond Halley, Carl Linnaeus, Charles Darwin, and Malthus himself.

The tragedy of the commons, it seemed, was a lens through which to understand our relationships with the world around us. And it had arrived at just the right time.

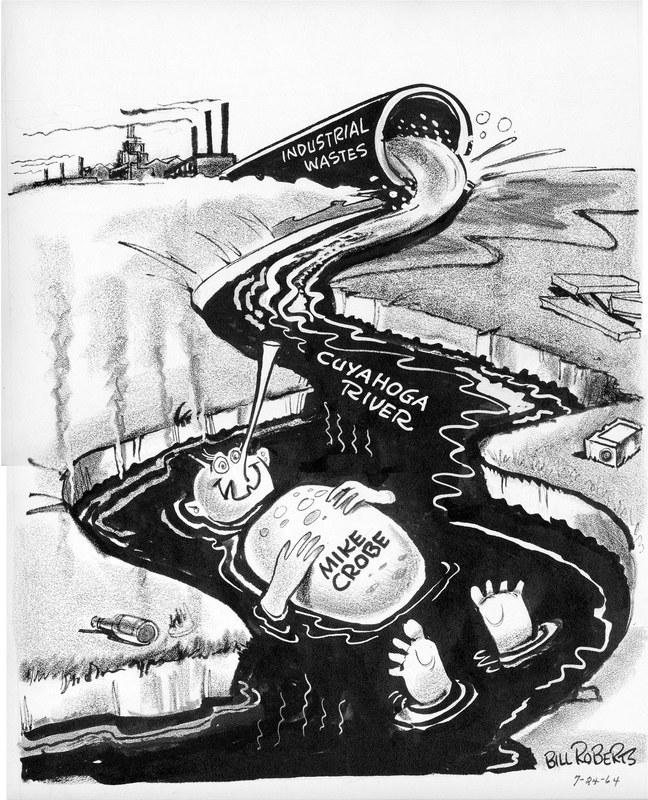

In 1962, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring had provided “the stimulus for a new intellectual revolution,” as Hardin later wrote, awakening the masses to the threat of environmental ignorance. Throughout the 1960s, reports of tropical deforestation and declining marine populations sparked further concern about humans’ undue influence. In 1969, the Cuyahoga River caught fire in Cleveland, Ohio, and 3 million gallons of oil spilled into the Pacific near Santa Barbara, bringing attention to pollution of the country’s waterways. Into this anxious moment, “Tragedy” entered with all the force of common sense and reason.

In Newfoundland, where the Atlantic cod population was already in steady decline, Hardin’s words hit with a heavy weight. In May 1976, following years of worrisome signs about the fishery’s health, the Fisheries and Marine Service published a book-length policy tract that identified “a conflict between individual interests and the collective interests” as the central problem.

“In an open-access, free-for-all fishery,” the report read, competition among fishermen disregarding the consequences of their actions was resulting in resource extinction, “repeating in a fishery context the tragedy of the commons.” What the fishery needed, the report suggested, was “a system of allocation by a body governing access to the resource.”

This argument for greater institutional oversight surely pleased Hardin, who believed the only way to address crises of the commons was to forsake commons altogether. Resources could be saved only by restricting access to them. In “Tragedy,” he identified two forces powerful enough to achieve such an end: privatization and government control. He described these methods as “mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon”—arrangements that could ensure responsibility and stave off the worst of our instincts.

Around the world, particularly in developing countries, Hardin’s argument became a framework for centralized resource management, adding momentum to a movement that had been building throughout the 1960s. In the 1970s, states including Lesotho and Ghana assumed ownership of forests that had long been managed collectively. Fisheries in the Netherlands and Iceland were privatized, kicking off a global trend. Pasture lands and other natural resources that were once commons were soon enclosed.

But even as these changes reflected growing agreement with Hardin’s mission to protect us from ourselves, a political scientist in Bloomington, Indiana, was building a body of evidence that showed tragedy was far from a foregone conclusion.

Consider the Lobster

Elinor Ostrom was born in Los Angeles in 1933, the only child of a musician and an out-of-work set designer who grew food in a backyard garden to help weather the Great Depression. Her mother secured her a spot at Beverly Hills High School, where she was a self-described “poor kid in a rich kid’s school.”

She joined the school’s debate team, where she learned that public policy questions always have multiple answers, a lesson she would carry. Success at Beverly Hills High opened the opportunity to study political science at UCLA, where she became the first in her family to attend college. She eventually earned a PhD despite objections from both the university, which was skeptical of a woman’s employment prospects in the field, and her first husband, whom she promptly divorced.

Her 1965 dissertation focused on groundwater management in Los Angeles, where, by the time she was born, unchecked development had depleted freshwater reserves and opened the door to billions of gallons of annual saltwater incursion from the coast. Ostrom focused on the West Basin, which runs down the coast from LAX to Long Beach. For years, a range of water agencies and industries had tapped this reserve like “robber barons,” she wrote. Withdrawals were three times the sustainable rate. Hardin might well have called it a tragedy of the commons. But Ostrom saw something more nuanced.

Recognizing their actions would lead to disaster, the water users formed the West Basin Water Association in the 1940s to improve information sharing, discuss mutual problems, and build trust. They cut back on their usage and developed a method to halt the saltwater’s advances, injecting freshwater back into the groundwater to form a barrier of sorts. By the 1980s, the basin was no longer critically overdrafted. And the solution hadn’t required ceding control of the basin to private or governmental oversight; instead, the resource users themselves had developed a network of stakeholders who formed committees and established policies to handle disputes or other issues that arose. “I was studying the commons from the beginning, but I didn’t know it,” Ostrom later said.

By the time Hardin published his famous essay, Ostrom had married fellow political scientist Vincent Ostrom and moved to Indiana University in Bloomington, where the two continued investigating commons governance. When she read “Tragedy,” Ostrom was taken aback. It didn’t reflect what she had seen in Los Angeles, nor in a number of other settings where commons had thrived. In the mountain meadows and forests of Switzerland and Japan, as on irrigated farmland in Spain and the Philippines, conservation collectives had held ruin at bay, sometimes for centuries.

Like a glimpse into the murky waters where the Atlantic cod once thrived, Hardin’s metaphor offered only a partial view. Through more than 500 case studies pulling from sociology, anthropology, history, economics, political science, forestry, and ecology, Ostrom and her colleagues identified a set of principles that bottom-up, community-led organizations had used to successfully manage commons. Among them were clearly defined boundaries for a commons; monitoring of the resource and its users; graduated sanctions for anyone who stepped out of line; and a mechanism for conflict resolution. Ostrom’s work showed these principles could be managed by people from any background absent the expertise of executives or bureaucrats.

“Humans have great capabilities, and somehow we’ve had some sense that the officials had genetic capabilities that the rest of us didn’t have,” Ostrom said late in life. “I hope we can change that.”

Maine’s lobster fishery offers a helpful example—and a counterpoint to Newfoundland’s tragic tale. As with the Atlantic cod, early American colonists found lobsters to be both abundant and enormous, teeming in tidal pools and measuring up to five feet long. Even a part-time fisher could catch a couple thousand a month to make a living in a young United States. By the 19th century, lobster fleets filled Maine’s harbors. As the industry advanced, canning eliminated the need to ship lobsters alive, and canners began processing any lobster they could find, even tiny adolescents that had not yet matured to breeding. Soon, the fishery faced imminent exhaustion.

A series of regulations, including an 1872 prohibition against taking egg-bearing females and an 1874 minimum-length law, brought stability and staved off collapse. But for much of the past century, the fishery has been managed by a community of lobster harvesters who organized territories, developed informal rules around trapping, and established extralegal means of sanctioning those who run afoul of accepted conservation practices.

Like so many of the commons Ostrom studied, Maine’s lobster fishery avoided the fate Hardin predicted, largely because its users acted in the collective interest. Its success is supporting evidence for Ostrom’s belief in the benefits of polycentricity, or layers of governance—in this case a marriage of state regulation and user-led resource management—that enable nuanced solutions incompatible with centralized governance.

If counterpoints to “Tragedy” exist in great numbers, across regions and resources, why did Hardin’s essay sink its teeth into our collective understanding of the commons?

Thomas Dietz, a frequent Ostrom collaborator, blames society’s tendency toward “catastrophism” and “simple, universal explanations.” As the authors of a retrospective paper put it in 2019, Hardin “contributed a catchphrase that caught the prevailing winds of public discourse,” even though the pasture metaphor was “reductionist and distorting.”

Such distortion was evident in Newfoundland, where “Tragedy” was used to blame local fishermen for the cod collapse and steer the fishery toward government oversight.

The fishing industry suffered from being over capacity, the 1976 report stated, “particularly the inshore part” where Newfoundlanders fished. Though inshore operations were more modest than their industrial counterparts in deeper waters, the report accused locals of failing to diversify their catch, putting further strain on the cod population. Inshore buyers were also more willing to accept improperly handled fish, compromising the fishery’s quality and sinking the market.

The larger offshore fleets weren’t blameless, the report acknowledged; they had a role in the congestion and ensuing conflicts that arose among fleets. But it was inshore where “the labor force far exceeds the industry’s capacity for employment,” resulting in “an unchecked scramble for advantage” that often appears “where an industry is based on a resource that belongs to all.”

Stability and equitable access, the report claimed, are “normally maintained or restored only through the imposition of controls by government.”

Misplaced blame is common when resource depletion is described as the product of such a scramble for advantage rather than a failure of management, says Bonnie McCay, an anthropologist who studied Newfoundland’s fisheries in the 1970s. “People don’t look carefully at what is actually causing the problem,” she says. “Where is it that a system is leading to failure to conserve for the future?”

Overuse of resources often stems from “the paradox of the state being present and absent at the same time,” says social anthropologist Tobias Haller. The cod collapse bears this out.

The International Commission for the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries had established quotas in 1970 for the total allowable catch, but overestimated cod’s abundance. In 1977 Canada declared jurisdiction over the fishery within 200 miles of its coast and later closed its ports to foreign vessels, but the measures were protectionist, not conservationist. The government bailed out Newfoundland’s seafood companies, merging them into a conglomerate, and resuscitated a Nova Scotian seafood company; both boomed in the 1980s as the cod population plummeted.

The real tragedy, Haller says, is the use of Hardin’s writing to justify the removal of commons.

In Ghana, for example, where political conflict led to centralized control of the forests, a 1988 report found Ghanaian forests were “even more vulnerable to the ‘tragedy of the commons’ than they were when property rights were vested in tribal groups, which had some incentive to maintain the resource.”

Hardin’s essay maintains its influence, Haller says, because it explains resource exhaustion in a way that continues to legitimize the funneling of power to the powerful, steering control of the commons away from the individuals who most rely on them and toward states and the private market.

Experts who study commons lament the real-world ramifications of Hardin’s writing, but the ideas undergirding his argument attract even more scrutiny. Because it wasn’t actually the conservation of natural resources or preservation of the environment that concerned him most when he wrote “Tragedy.” It was the specter of untold disasters caused by “the evils of overpopulation.” And the solutions he suggested were unorthodox.

Lessons from a Farm

Spending the summers of his youth on the family farm, Hardin had watched as strangers from nearby Kansas City drove out to the country to abandon unwanted cats. These people hoped the cats would find a good home, but he saw what really happened. Inevitably, the farm’s dogs would kill the cats, or their population would build up until a fever swept through and wiped them out. When nature failed to control the cats’ numbers, his uncle stepped in to kill the “superfluous” cats himself, Hardin said. Observing this cycle, he learned a lesson that stuck.

“All my life, I have been haunted by the realization there simply isn’t room for all the life that can be generated, and the people who refuse to cut down on the excess population of anything are not being kind; they are being cruel,” he said.

The search for answers to this population problem had led him into the lab early in his career, but by the 1960s he found a new outlet for his anxiety: advocacy for abortion rights and birth control. Beginning in 1963, a decade before Roe v. Wade, Hardin spoke regularly on college campuses in their favor. In 1966’s “The History and Future of Birth Control,” he extolled “the great virtues of the progesterone pill” and questioned the morality of researchers in American labs who halted investigations into abortifacients “for fear of success.” He even helped women, including students at his university, travel to Mexico to receive abortions, and testified before Congress about abortion legislation, among other issues.

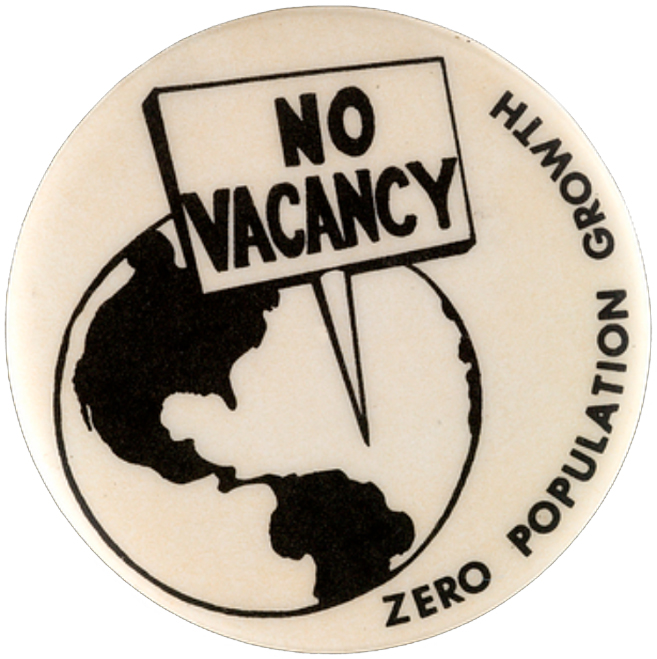

At every step, Hardin’s focus was on how birth control and abortion access could curb a global population then growing at 2% each year and, in turn, the environmental destruction he felt was being wrought. He found common cause in Paul Ehrlich, a Stanford entomologist and coauthor of 1968’s The Population Bomb, a harrowing book that promised the impending death of hundreds of millions as a result of unchecked population growth and inadequate food supplies. “The battle to feed humanity is already lost,” Ehrlich wrote, doomed by “a record of ecological stupidity without parallel.”

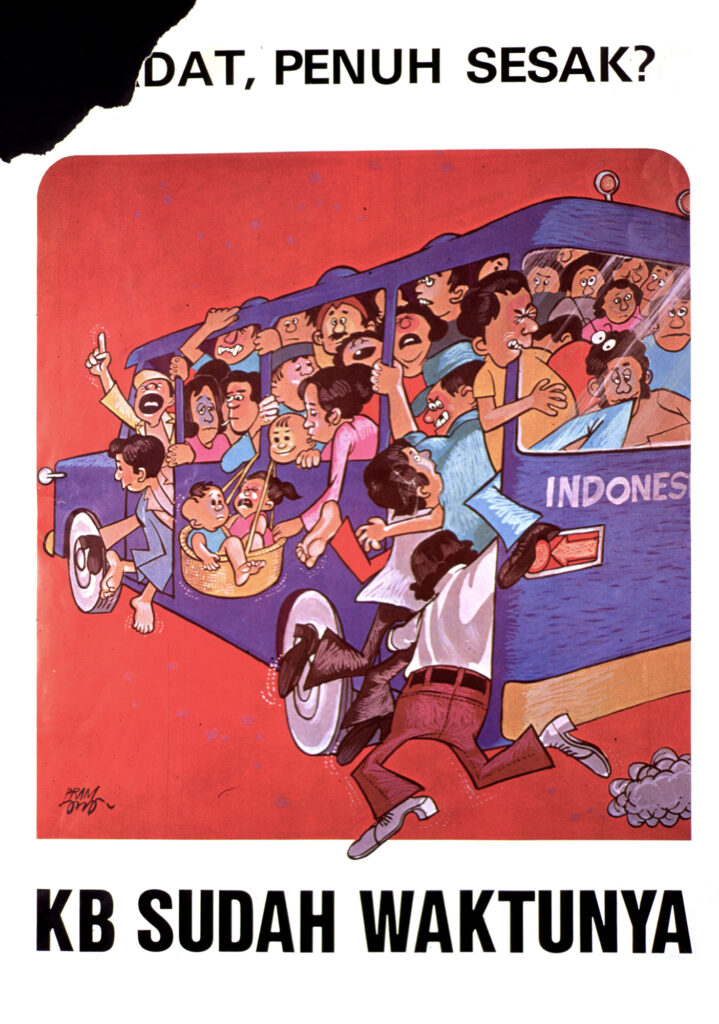

The book was sensational and fantastical, warning that the decades to come would be full of food riots, global conflict, food and water rationing, continent-spanning famines and plagues, and nuclear annihilation. It sold millions of copies, fomented a fervor about overpopulation, and landed Ehrlich on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Amid growing concern about population growth, programs were established around the world to reduce fertility and reproduction, including China’s “one-child” policy.

Ehrlich had helped fuel a pervasive sense that humanity was at a tipping point. Hardin readily offered ways to pull back from the brink, including in “Tragedy,” in which he claimed the population problem was impervious to a technical solution and instead required “a fundamental extension in morality.” Hardin’s morals, though, were dubious.

“Freedom to breed is intolerable,” Hardin writes in “Tragedy,” revealing his true conviction.

To Hardin, Earth was a lifeboat with limited carrying capacity. “Complete justice”—tending to the needs of all, like those cats on the farm—would lead to “complete catastrophe,” as he later wrote. Poor countries—and poor people—were responsible for the lion’s share of population growth; it was the responsibility of wealthy countries to limit their fertility rates, he argued.

In “Tragedy,” he declared opposition to the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights for its insistence that each family should be allowed to choose its own size. In doing so, he acknowledged, “one feels as uncomfortable as a resident of Salem, Massachusetts, who denied the reality of witches in the 17th century.” The fastest-growing populations were the most miserable and their misery was bound to spread, he believed.

A world food bank, in which wealthy nations supported the needs of developing ones, was “a commons in disguise”; if it were created, “poor countries [would] not learn to mend their ways” and limit their growth. In questioning the agricultural advances of Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution, he repeated Rockefeller Foundation vice president Alan Gregg, who compared the spread of humanity to the spread of cancer: “cancerous growths demand food; but, as far as I know, they have never been cured by getting it.”

Hardin supported the end of international aid in food, agriculture, and medicine; approved of sterilization; and advocated the segregation of nations by ethnicity and religion. He said that “a multiethnic society is insanity,” and signed onto “Mainstream Science on Intelligence,” a Wall Street Journal editorial that argued IQ tests provided scientific evidence of Black Americans’ inferior intelligence. His support for abortion rights and birth control often emphasized developing nations and “feeble-minded individuals.”

UCSB, where he taught until his death in 2003, issued a statement last year calling his nativist, ableist, and eugenicist views “morally repugnant and ethically reprehensible.” “Tragedy,” in particular, was “not based on an engagement with scientific evidence and promoted an ideological agenda.”

Hardin acknowledged that by the time the essay was published he had long since abandoned scientific practice and become “a wolf in sheep’s clothing” who would have struggled to reach tenure at his newly research-oriented university. Nonetheless, three-quarters of U.S. educators in environmental science and sustainability still believe the tragedy of the commons is a fundamental dilemma of resource sharing, according to a 2019 study that surveyed 275 undergraduate instructors. More than one-third believe it represents the foremost thinking on the commons.

“[Hardin’s] ideology remains a cornerstone of the way that people think about the importance of science to society,” says Lina-Maria Murillo, a professor of history and gender studies who has studied Hardin’s influence on abortion and birth control. “It’s earth-shaking to me.”

Learning How to Manage Commons

Even though Hardin’s writing has been countered and critiqued and many of his arguments invalidated, he retains a stubborn hold on our environmental imagination. When U.N. member states committed to 17 sustainable development goals in 2015 to “end poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere,” Hardin’s name wasn’t mentioned, but his ideas were, Haller says. His spirit lives on in international agreements that insist on top-down institutions as the mechanism to address climate change, biodiversity loss, and natural resource exhaustion.

“In the sustainable development goals, you don’t find the word commons. It’s not there, just governments and the private sector—powerful actors,” Haller says. “The whole rest of the world, meaning us and Indigenous groups around the world, are not included. And we know very well that where we are now is actually because of states and private owners.”

Commons—and those who maintain and rely on them—are more important than ever to environmental health, Haller says, and leaving them out of the discussion risks their continued enclosure and further degradation.

Ostrom, too, felt the need for a more expansive approach to solving social dilemmas, considering not just political leaders and interest groups but average citizens as well. She argued for an education system that shared research on collective action with high school and undergraduate students, lest it produce “generations of cynical citizens with little trust in one another.” Hardin believed people were “locked into a system,” but Ostrom saw that with the right tools and support, they could avoid a tragic fate. The concept of mutual benefit was as much a part of human nature as self-interest.

For many scholars, Ostrom’s optimism is an antidote to Hardin’s pessimism—and a more relevant way of thinking about the great challenges we now face. The fundamental lesson of her work, Dietz says, is that we can learn how to manage the commons, both locally and globally.

Photographs from the Ostroms’ tours of farmer-managed irrigation systems in Nepal. Left, Dang Valley farmers repairing an irrigation canal after discovering an unapproved diversion by another farmer, who was sanctioned, April 1990. Right, Elinor Ostrom watches farmers in the Chitwan District dig a drain channel along a road, March 1993. (Digital Library of the Commons/Indiana University Libraries)

“These are very difficult challenges. They are tough and they often get screwed up. That can have tragic consequences,” Dietz says. “But we can learn how to do it well. We have in the past.”

The 1987 Montreal Protocol, which phased out the production of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), is one example of international management of a crisis in the global commons. In that case, scientists realized human activity—the use of aerosol sprays, refrigerants, and other human-made compounds containing CFCs—would have unintended environmental consequences, including the death of critical phytoplankton, crop failure, and skin cancer. The public recognized the risks, the world’s governments acted, and the ozone layer is recovering. This is the role science can play in the future of commons, from the small scale to the global.

In 2009, Ostrom was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for disproving the tragedy of the commons. She died in 2012, just as her principles were beginning to filter into conversations about climate change. Despite this recognition, Hardin’s writing in “Tragedy” remains “the defining concept in climate conversations,” says Aseem Prakash, a professor of environmental politics, who labels Hardin “a false prophet and a highly problematic one.”

In the end, continued reverence for Hardin’s ideas may lead to the tragedy he feared.

Such a Silly Story

In 2006 cod fishing came back to Newfoundland. The moratorium remained in place, but the Canadian government established what it called a stewardship fishery, allowing the inshore fleet to land a modest haul—just a fraction of the quota for 1992—in order to “obtain a better understanding of the stock.” Little has changed in the Atlantic since then, according to scientists who say the stock is still stagnant, unhealthy.

Nonetheless, the government announced the end of the moratorium in June 2024. It called the move “a historic milestone.”

Though politicians sold the move as a great comeback story, the details revealed something less hopeful. The total allowable catch was set at less than 10% of the 1992 quota, which itself was a far cry from the days when cod was king. And the decision to switch the fishery to a commercial designation would bring back the international harvesters who once contributed to the collapse, fisheries union president Greg Pretty said. He lamented that the government was caving to “corporate masters.”

Scientists, meanwhile, worried the move would prolong the cod’s peril; the stock has not grown since 2016. Even with no fishing at all, there is moderate risk of population decline in the coming years, owing largely to a population collapse in the tiny capelin that cod rely on for sustenance. Rather than an optimistic epilogue, the decision appeared to be an attempt to rewrite the cod’s story by the same institutional forces that enclosed the commons and sealed its fate.

George Rose, a scientist who spent 40 years studying Atlantic cod, including at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, said the announcement was anything but cause for celebration. “DFO has thrown in the towel,” he said. “We never seem to learn.”

Late in his life, Hardin wrote about another animal—the ostrich, famous for burying its head in sand. By ignoring the taboo of overpopulation, he said, we were all becoming the ostrich.

But, as Hardin noted, the ostrich doesn’t actually bury its head. The metaphor was based on a myth. It didn’t reflect reality, even though it had seeped into the public consciousness.

He then asked an ironic question: “What accounts for the endurance of such a silly story?”